Qigong (Chi Kung) is

a product of the twentieth century, but is rooted in the earlier tradition. The

term qi (pneuma, breath) is mentioned in the Chinese Tang (618- 907) and Song

(960-1127) period. In modern times, it has taken on a new meaning and refers

not only to Nourishing Life (yangsheng) but also to

martial and therapeutic techniques.

The idea of

"nourishing" (yang) is commen in Chinese

thought: one can nourish life (yangsheng), the inner

nature (yangxing), the body (yangxing),

the whole person (yangshen), the will (yangzhi), and the mind (yangxin).

The term yangsheng designates techniques based on the

essence, the inner or outer breath, and the spiritual force (jing, qi, shen); these techniques

are grounded on physiological, psychological, and behavioral principles and

include gymnastics (daoyin), massage, breathing (fuqi, xingqi), sexual hygiene (fangzhong shu), diets (bigu), healing, visualizations , and rules of daily

behavior. One of the earliest documents where similar practices are mentioned

is in the Mawangdui manuscripts dating to about 200 BCE. Discovered in 1973.

The term qigong

however, signifies both "practice" and "efficiency" of qi,

it can embrace all types of techniques, both traditional and modern.

Depending on the

doctrinal and social context of these practices, historians currently divide

qigong into six branches: a Taoist qigong, a Buddhist qigong, a Confucian

qigong, a medical qigong, a martial qigong, and a popular qigong (including the

methods of rural exorcists and sorcerers). According to the features of the

practice, they also distinguish between a "strong qigong" (ying

qigong), incorporating martial techniques, and a "soft qigong" (ruan

qigong). The latter is further divided into two groups:

1. Jinggong, or the practice of qi in rest, which

traditionally was called "sitting in oblivion" (zuowang)

by Taoists, "sitting in dhyana" (chanzuo)

by Buddhists, and "quiet sitting" (jingzuo)

by Neo-Confucians. These sitting practices can be accompanied by breathing,

visualization, and mental concentration.

2.Donggong, or the

practice of qi in movement, which includes the gymnastic traditions (daoyin) of medical doctors, Taoists, and Buddhists. The

induction of spontaneous movements (zifa donggong) is derived from traditional trance techniques (Despeux 1997).

New practices

essentially created in the 1980s were much debated and criticized by

traditional religious personalities, qigong followers, and authorities.

Certain practices, such as the "Soaring Crane form" (hexiang zhuang), lead to

spontaneous movements that were said to cause illness, probably because of

their close connection with trance states. Some techniques that emphasize

collective practices and promote the establishment of a so-called "area of

qi" (qichang) to increase efficiency were also

strongly criticized; for instance, the method taught by Yan Xin , a master who

organized collective qigong sessions in stadiums with a capacity of up to about

ten thousand, was very popular but aroused suspicion among the authorities. As

for the therapeutic technique of the qigong master who heals people at a

distance through his energy or his hands-a method that actually revives the

traditional Taoist practice of "spreading breath" (buqi)-the possible existence of an "outer

energy" (waiqi ) and its efficacy have been

debated at length.

Official qigong

institutions appeared in the 1950s and 1960s and were at first exclusively

concerned with therapeutics. One of the main qigong promoters at the time was

Liu Guizhen (1920-83). A mend of Mao Zedong, he

returned to his village after developing a stomach ulcer and practiced breathing

and meditation exercises under a Taoist master. Later he created a new method

called "practice of inner nourishment" (neiyang

gong) and founded qigong therapy institutes in Tangshan mill (Hebei) in 1954

and in Beidaihe (Hebei) in 1956. These institutes

were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, and then partly reconstructed

after 1980 when qigong flourished again.

From that time,

qigong began to invade the town parks where masters and followers practice in

the morning. Some religious personalities who described themselves as

"qigong masters" felt encouraged to revive forgotten or little known

practices, or to create new techniques based on the traditional ones. Qigong

had both enthusiasts and critics among the authorities. Although its

therapeutic function was always essential, certain officials wanted to move

qigong beyond the realm of individual practice and propound it to the masses

and to society, even to the state, because they saw in it economic advantages

and the possibility of asserting the specific identity of China, its power and

its modernity, Qigong was taught in schools and universities and became the object

of international congresses and scientific research, and numerous specialized

journals and books were published on the subject. Other officials viewed it as

charlatanism and superstition, and mistrusted the subversive potential of

certain movements. An example is the Falun gong (Practices of the Wheel of the

Law), a form of qigong allegedly rooted in the Buddhist tradition, which in

1999 organized demonstrations in Beijing and other Chinese cities and was

outlawed shortly afterward.

What we

euphemistically refer to as “the Politics of Qigong” thus is when qigong

entered the political arena.

An early example of

this was Taiping dao (or Way of Great Peace) rebellion, organized in 184. Also

called the Yellow Turban rebellion, it represented a critical factor in the

fall of the Han dynasty and was one of the movements that contributed to the

milieu from which Taoist religion arose. It is presumed that they used the Taipingjing (one of the earliest Taoist scriptures) as

central text and inspiration. (Benjamin Penny in, The Encyclopedia of Taoism,

2008, p.1156.)

The doctrine of the

Taiping jing is based on the idea, already present in

Warring States texts, that an era of Great Peace (taiping)

will descend on the empire if its governance is based on returning to the Dao.

The slogan used by

the Yellow Turbans was, "The Blue Heaven (qingtian)

is already dead, the Yellow Heaven (huangtian) will

replace it." This is often read in political terms as conforming to the

movement of the five elemental phases (wuxing). As

each phase was accorded a color, the cycle of dynasties was seen to follow a

cycle of colors. Since the Han ruled under the phase of Fire, the subsequent

dynasty had to rule under Soil, and the color attributed to Soil was yellow.

Thus, the idea that the Yellow Heaven was about to be established signaled the

movement's revolutionary intentions. However, for this reading to be consistent

the Yellow Turbans should really have referred to the demise of the Red Heaven,

the color adopted by the Han. It is the idea that the Yellow Heaven presaged

the new society of Great Peace led to the adoption of the yellow headscarves (huangjin turbans is the traditional rendering) that gave

rise to their name. Other examples of politicized notions of yangsheng or qigong, follow underneath.

Like the various

forms of yoga, qigong and Chinese (inner) Alchemy, exist of various

extremely detailed spiritual practices and belief system that are not a

religion itself yet can be found to be incorporated into many different

religious traditions as well as into non-religious traditions such as medicine,

martial arts, and secular scientific inquiry. The Politics

of Qigong in Modern China P.1.

In 2006, the Chinese

Government ordered the closure of Bingdian Weekly

because the weekly argued that “official textbooks inaccurately depicted the

1900 Boxer Rebellion, a nationalist uprising” in which thousands of Chinese

Christians and many foreigners were killed. Not surprising, in the same article

the WSJ also concluded,” Beijing ’s anxiety over a news media that is

increasingly driven by market forces and a burgeoning sense of professionalism,

rather than official propaganda directives. Authorities have jailed several

Chinese journalists in the past two years and moved to tone down feistier

publications.” (WSJ, China Shuts Down Outspoken Publication, January 25, 2006

9:13 a.m.) P.2: The Celestial and Terrestrial Spirits of

Qigong:

Introduction to Politics of Qigong P.3 to 5

about the Taiping Rebellion.

Of the great Eurasian states beyond Europe, China (and to a lesser degree

Japan) had always been the richest, strongest and least accessible to European

influence. Politics of Qigong P.3.

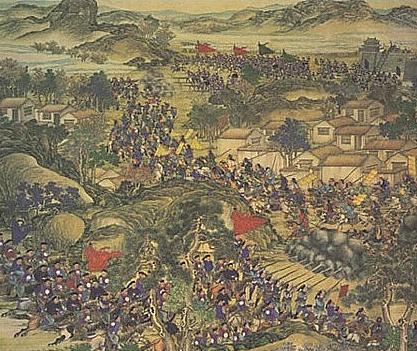

TheTaiping Rebellion. It began in South West China with the

visions of a millenarian prophet. Politics of

Qigong P.4.

Politics

of Qigong P.5: End of Taiping, Burying the Dead.

Politics

of Qigong P.6: The Boxer Uprising.

Politics

of Qigong P.7: Chinese security

officials did not expect the sudden appearance of the Falun Gong, whose members

surrounded government offices in Beijing, though the organization had operated

as a legal entity registered under Chinese regulations. Falun Gong.

For updates

click homepage here