By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

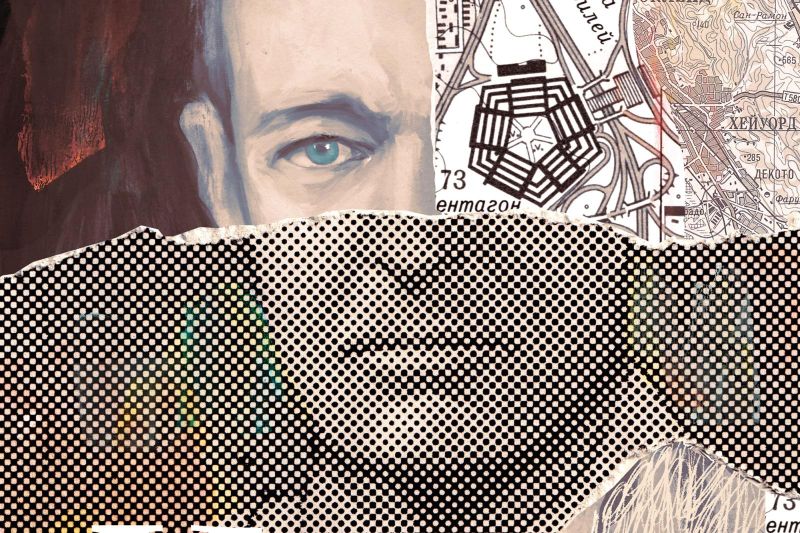

From Old To New Cold War

Caught on Camera, Traced by Phone: The Russian Military Unit That Killed Dozens

in Bucha

The Potsdam

Conference, according to Hugh Lunghi (British

military interpreter and veteran of World War II), was bad-tempered’. The

alliance of personalities that held things together was dissolving. Roosevelt

would be out of office within days, replaced by Clement Attlee. By the end of

the Potsdam gathering, only Stalin would remain from the wartime Big Three

leaders. late in February 1946, George Kennan, the No. 2 at the U.S. Embassy in

Moscow, sent his momentous “long telegram” to the State Department analyzing

Stalin’s malign designs on Europe and sketching a containment strategy

Thus we all

read George Kennan, For although there were other important figures

in modern U.S. foreign relations, only one was George Kennan, the “father of

containment,” who later became an astute critic of U.S. policy and a

prize-winning historian. We dissected Kennan’s famous “Long Telegram” of

February 1946, his X” article in these pages from the following year,

and his lengthy and unvarnished report on Latin America from March 1950. We

devoured his slim but influential 1951 book, American Diplomacy, based on

lectures he gave at the University of Chicago; his memoirs, which appeared in

two installments in 1967 and 1972 and the first of which received both the

Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award; and any other publication he wrote

that we could get our hands on. ( there was no skipping Russia Leaves the War,

from 1956, as it won not only the same awards garnered by the first volume of

his memoirs but also the George Bancroft Prize and the Francis Parkman Prize.)

And we dove into the quartet of essential studies of Kennan, then coming out in

rapid succession by our seniors in the guild—David Mayers,

Walter Hixson, Anders Stephanson, and Wilson

Miscamble.

Even then, some of us

wondered whether Kennan was as important to U.S. policy during the early Cold

War as numerous analysts made him out to be. He may be considered an architect

of American strategy, not the architect. Perhaps the most that could be said

was that he gave a name—containment—and a specific conceptual focus to a

foreign policy approach already emerging, if not in place. Even at the Potsdam

Conference in mid-1945, after all, well before either the Long Telegram or the

“X” article, U.S. diplomats understood that Joseph Stalin and his lieutenants

were intent on dominating those areas of Eastern and Central Europe that the

Red Army had seized. Officials determined that little could be done to thwart

these designs, but they vowed to resist Kremlin leaders' efforts to move

farther west. Likewise, the Soviets would not be permitted to interfere in

Japan or be allowed to take control of Iran or Turkey. This was containment in

all but name. By early 1946, when Kennan penned the Long Telegram from the

embassy in Moscow, the wartime Grand Alliance was but a fading memory; by then,

the anti-Soviet sentiment was a stock feature of internal U.S. policy

deliberations.

Still, the 1946

telegram and the 1947 article were remarkable pieces of analytical writing that

explained much about how U.S. officials saw the postwar world and their

country’s place in it. That Kennan soon began to distance himself from

containment and to claim that he had been grievously misunderstood, that the

policy in action was turning out to be more bellicose than he had envisioned or

wanted, only added to the intrigue. Was he more hawkish regarding Moscow in

this early period than he later claimed? Or had he merely been

uncharacteristically loose in his phrasing in these writings, implying a

hawkishness he did not feel? The available evidence suggested the former, but

one held off final judgment, pending the full opening of Kennan’s personal

papers and especially his gargantuan diaries, which spanned 88 years and ran to

more than 8,000 pages.

These materials were

indeed rich, as the world learned with the publication of John Lewis Gaddis’s

authorized biography, three decades in the making, which appeared to wide

acclaim in 2011 and won the Pulitzer Prize. Gaddis had full access to the

papers and made extensive and incisive use. Then, in 2014, the publication of

The Kennan Diaries a 768-page compendium of entries ably selected and annotated

by the historian Frank Costigliola. Scholars had long

known about Kennan’s prickly, complex personality and tendency toward

curmudgeonly brooding, but the diaries laid bare these qualities. What emerged

was a man of formidable intellectual gifts, sensitive and proud, expressive and

emotional, ill at ease in the modern world, prone to self-pity, disdainful of

what he saw as America’s moral decadence and rampant materialism, and given to

derogatory claims about women, immigrants, and foreigners.

Yet in one key

respect, Kennan’s diaries proved unrevealing. Like many people, Kennan

journaled less when he was busy, and there is virtually nothing of consequence

from 1946 or 1947, when he wrote the two documents on which his influence

rested and when he began to reconsider fundamental assumptions about the nature

of the Soviet challenge and the preferred American response. For the entirety

of 1947, arguably the pivotal year of the early Cold War and Kennan’s career,

there is a single entry: a one-page rhyme. Any serious assessment of Kennan’s

historical importance—How deeply did he shape U.S. policy at the dawn of the

superpower struggle? When and why did he sour on containment as practiced? Is

it proper to speak of “two Kennans” concerning the

Cold War?—it must center on this period of the late 1940s.

Now Costigliola has come out with a full-scale biography of the

man, from his birth into a prosperous middle-class family in Milwaukee, in

1904, to his death in Princeton, New Jersey, in 2005. (What a century to live

through!) It is an absorbing, skillfully wrought, at times frustrating book,

more than half of which is focused on the diplomat’s youth and early career. Costigliola’s unmatched familiarity with the diaries is on

full display. Although he does not shy away from quoting from some of their

more unsavory parts, his overall assessment is sympathetic, especially

vis-à-vis the “second” Kennan, who decried the militarization of containment

and pushed for U.S.-Soviet negotiations. Kennan, he writes, was a “largely

unsung hero” for his diligent efforts to ease the Cold War.

Intriguingly, as Costigliola shows but could have developed more fully,

these efforts were already underway in the late 1940s while the superpower

conflict was still in its infancy. This transformation in Kennan’s thinking is

especially resonant today, in an era that many analysts call the early stages

of yet another cold war, with U.S.-Russian relations in a deep freeze and China

playing the role of an assertive Soviet Union. If the analogy is correct, it

bears asking: How did Kennan’s thinking change? And does his evolution hold

lessons for his successors as they forge policy for a new era of conflict?

Our Man In Moscow

Kennan’s love of

Russia came early and partly because of family ties: his grandfather’s cousin, also

named George Kennan, was an explorer who achieved considerable fame in the late

nineteenth century for his writings on tsarist Russia and for casting light on

the harsh penal system in Siberia. Soon after graduating from Princeton in

1925, the younger Kennan joined the Foreign Service and developed an interest

in the country; in time, it became much more. Costigliola

writes, “Kennan’s love for Russia, his quest for some mystical

connection—impulses that stemmed in part from the hurt and loneliness in his

psyche going back to the loss of his mother—had enormous consequences for

policy.” That is a pregnant sentence indeed, with claims that would seem hard

to verify, but there can be no doubt that Kennan’s passion for

pre-revolutionary Russia and its culture was real and abiding, staying with him

to the end of his days.

In the late 1920s and

early 1930s, as an ambitious young State Department officer, Kennan toggled

between Germany, Estonia, and Latvia, working hard to develop Russian language

facilities and serving from 1931 to 1933 at the Soviet listening post in Riga.

An intense, exhilarating, draining period followed in the U.S. embassy in

Moscow under the mercurial ambassador William Bullitt. Costigliola

finds the middle of the decade to be a formative period for Kennan—he devotes

an entire 48-page chapter to “The ‘Madness of ’34,’” and another of equal

length to the years 1935–37, writing, in effect, a small book within a book and

adding much to our understanding of Kennan’s worldview—as the diplomat worked

to the point of exhaustion to establish himself as the premier Soviet expert in

the Foreign Service.

Kennan treasured

Russians as a warm and generous people but looked askance at Marxist-Leninist

ideology, speculating even then that Russian communism was headed toward

ultimate disintegration because of its disregard for individual expression,

spirituality, and humanism diversity. He had scarcely better things to say

about Western capitalism: it was characterized by systemic overproduction,

crass materialism, and destructive individualism. He disliked and distrusted

the “rough and tumble” of his own country’s democracy and longed for rule by an

“intelligent, determined ruling minority.”

During World War II, Kennan

served first as the chief administrative officer of the Berlin embassy and

then, after a brief assignment in Washington in 1942, as second-in-command at

the U.S. diplomatic mission in Lisbon. The top U.S. representative at the post,

Bert Fish, seldom set foot in the building, which left Kennan to negotiate base

rights in the Azores with Portugal’s premier, António de Oliveira Salazar,

whose dictatorial but anti-Nazi rule Kennan admired. He grew disenchanted, by

contrast, with U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s wartime diplomacy. He

opposed the president’s demand that Germany and Japan unconditionally

surrender, as it foreclosed the possibility of a negotiated settlement. And

after returning to the Moscow embassy in mid-1944, he faulted as naive Roosevelt’s

belief that the United States could secure long-term cooperation with Stalin.

Both then and later, Costigliola maintains, Kennan

failed to detect Roosevelt’s underlying realism and shrewd grasp of power

politics, as he continually mistook the president’s public statements for his

private views. He missed the degree to which, despite their differences, he and

Roosevelt “agreed on the fundamental issue of working out with the Soviets

separate spheres of influence in Europe.”

About the subsequent

Cold War, Costigliola is unequivocal: it need not

have happened and, having broken out, need not have lasted nearly as long as it

did. This argument is less novel than the book implies. Still, the author is

correct that “the story of Kennan’s life demands that we rethink the Cold War

as an era of possibilities for dialogue and diplomacy, not the inevitable

series of confrontations and crises we came to see.”

All the more

puzzling, then, that Costigliola gives scant

attention to the sharp downturn in U.S.-Soviet relations that began in the fall

of 1945, as the two powers clashed over plans for Europe and the Middle East.

He notes in passing that Kennan was “unaware how rapidly U.S. opinion and

policy were souring on Russia” in this period, but he does little to contextualize

this important point. The schism over the Soviet occupation of Iran goes

unmentioned, and readers learn nothing of Washington’s decision in early 1946

to abandon atomic cooperation with Moscow. And if indeed Kennan was incognizant

of how swiftly American views and policy were changing as the year turned, how

is this ignorance to be explained?

“X” Marks The Spot

Costigliola is undoubtedly correct to note Kennan’s transformation

from a position of opposing negotiations with the Kremlin in 1946 to one of

advocating them in 1948. But one wants to know more about this metamorphosis. Costigliola is authoritative (if, especially compared to

Gaddis, terse) on the Long Telegram and the “X” article. Still, one wishes for

more context—even in a biography—especially concerning 1947, when the latter

piece appeared. There is no discussion, or even mention, of the crises in

Greece and Turkey that raged during that year; of President Harry Truman’s

speech to a joint session of Congress, in which he asked for $400 million in

aid for the two countries and articulated what became known as the Truman

Doctrine, by which the United States pledged to “support free peoples who are

resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures”;

or of the 1947 National Security Act, which was closely tied to the perceived

Soviet threat and which gave the president vastly enhanced power over foreign

affairs.

As other sources reveal,

Kennan objected to the expansive nature of Truman’s speech and what it implied

for policy. But he chose not to alter the “X” article—still in production—by

emphasizing his desire for limited containment. Appearing in these pages in

July under the pseudonym “X” and the title “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” the

essay was widely seen as a systematic articulation of the administration’s

latest thinking about relations with Moscow, as its author laid out a policy of

“firm containment, designed to confront the Russians with unalterable

counter-force at every point where they show signs of encroaching upon the

interests of a peaceful and stable world.” Kennan seemed to say that diplomacy

was a waste of time for the foreseeable future. Stalin’s hostility to the West

was irrational and unjustified by any U.S. actions. Thus, the Kremlin could not

be reasoned with; negotiations could not be expected to ease or eliminate the

hostility and end the U.S.-Soviet clash. The Soviet Union, he wrote, was

“committed fanatically to the belief that with the United States there can be

no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the

internal harmony of our society be disrupted, our traditional ways of life are

destroyed, the international authority of our state be broken, if Soviet power

is to be secure.”

The assertion likely

raised few eyebrows among Foreign Affairs readers during the tense summer of

1947. But only some people in the establishment were convinced. The influential

columnist Walter Lippmann railed against Kennan’s essay in a stunning series of

14 articles in The New York Herald Tribune in September and October that

were parsed in government offices worldwide. The columns were then grouped in a

slim book whose title, The Cold War, gave a name to the superpower competition.

Lippmann did not dispute Kennan’s contention that the Soviet Union would expand

its reach unless confronted by American power. But to his mind, the threat was

primarily political, not military.

Moreover, Lippmann

insisted that officials in Moscow had genuine security fears and were primarily

motivated by a defensive determination to forestall the resurgence of German

power. Hence their decision to seize control of Eastern Europe. It distressed

Lippmann that Kennan and the Truman White House seemed blind to this reality

and to the possibility of negotiating with the Kremlin over issues of mutual

concern. As he wrote,

The history of

diplomacy is the history of relations among rival powers, which did not enjoy

political intimacy and did not respond to appeals to common purposes.

Nevertheless, there have been settlements. Some of them did not last very long.

Some of them did. For a diplomat to think that rival and unfriendly powers

cannot be brought to a settlement is to forget what diplomacy is all about.

There would be little for diplomats to do if the world consisted of partners,

enjoying political intimacy, and responding to common appeals.

Containment as

outlined by Kennan, Lippmann added, risked drawing Washington into defending

any number of distant and nonvital parts of the world. Military commitments in

such peripheral areas might bankrupt the Treasury and would, in any event, do

little to enhance U.S. security. American society would become militarized to

fight a “Cold War.”

Kennan was stung by

this multipronged, multiweek takedown, which Costigliola

oddly does not discuss. The diplomat admired Lippmann’s stature as perhaps

Washington's most formidable foreign policy analyst. He felt flattered that the

great man would devote so much space to something he had written. More than

that, he agreed with much of Lippmann’s interpretation, including Moscow’s

defensive orientation and the need for U.S. strategists to distinguish between

core and peripheral areas. “The Soviets don’t want to invade anyone,” he wrote

in an unsent letter to Lippmann in April 1948, adding that his intention in the

“X” article had been to make his compatriots aware that they faced a long

period of complex diplomacy when political skills would dominate. Once Western

Europe had been shored up, he assured Lippmann, negotiations under

qualitatively new conditions could follow.

In the months

thereafter, Kennan, now director of the newly formed Policy Planning Staff in

the State Department, began to decry the militarization of containment and the

apparent abandonment of diplomacy in Truman’s Soviet policy. He pushed for

negotiations with the Kremlin, just as Lippmann had earlier. His influence

waning, Kennan left the government in 1950, returning for a brief stint as

ambassador to Moscow in 1952 and later, under President John F. Kennedy, a long

spell as ambassador to Yugoslavia.

Out Of The Arena

So began George

Kennan’s second career, as a historian and public intellectual, from a perch at

the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. It would last half a century. Costigliola is consistently fascinating here, even if he is

less interested in Kennan’s writings and policy analysis than in his deep and

deepening alienation from modern society and his strenuous efforts to curate

his legacy. Readers get almost nothing on American Diplomacy, Kennan’s

important, realist critique of what he called the “legalistic-moralistic”

approach to U.S. foreign policy, or on the two volumes of memoirs, the first of

which must be considered a modern classic. Costigliola

says little about Kennan’s analysis of the U.S. military intervention in

Vietnam (he was less dovish in 1965–66 than Costigliola

implies) but a great deal about his loathing of the student protesters—with

their “defiant rags and hairdos,” in Kennan’s words—against the war. As

elsewhere in A Life Between Worlds, more would have been better. Readers

deserve more, for example, on what the diplomat-historian made of the crises

over Berlin and Cuba under Kennedy in the early 1960s or on how he interpreted

the severe worsening of superpower tensions under Jimmy Carter in 1979–80.

More and more, as the

years passed, Kennan felt underappreciated. Never mind the literary prizes,

accolades, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom presented to him by President

George H. W. Bush in 1989. On more days than not, he was a Cassandra,

despairing at the state of the world and his place in it, worried about how he

would be remembered. Thrilled to secure Gaddis, a brilliant young historian, as

his biographer, he grew apprehensive, especially as it became clear that Gaddis

did not share his low opinion of U.S. Cold War policy in general and nuclear

strategy under President Ronald Reagan in particular. (Another worry: that

Gaddis would be too distracted by other commitments to complete the work in a

timely fashion, thus allowing supposedly less able biographers—“inadequate

pens,” Kennan called them—to come to the fore.)

Even the Soviet

Union’s collapse in 1991 brought Kennan little cheer. For half a century, he

had predicted that this day would come. Still, one finds scant evidence of

public or private gloating, only frustration that the Cold War had lasted so

long and concern that Washington risked inciting Russian nationalism and

militarism with its support for NATO expansion into former Soviet domains. The

result, he feared, could be another cold war. In the fall of 2002, at 98, he

railed against what he saw as the George W. Bush administration’s heedless rush

into war in Iraq. The history of U.S. foreign relations, he told the press,

showed that although “you might start a war with certain things on your mind .

. . in the end, you found yourself fighting for entirely different things that

you had never thought of before.” It dismayed him that the administration

seemed to have no plan for Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein. He doubted

the evidence about the country’s supposed weapons of mass destruction. For that

matter, he argued, if it turned out Saddam had the weapons or would soon

acquire them, the problem was in essence, a regional one, not America’s

concern.

All the while, Kennan

condemned what he saw as the abuses of industrialization and urbanization and

called for a restoration of “the proper relationship between Man and Nature.”

In the process, Costigliola convincingly argues, he

became an early and prescient advocate of environmental protection. And all the

while, his antimodernism showed a retrograde side, as

he looked askance at feminism, gay rights, and his country’s increasing ethnic and

racial diversity. Maybe only the Jews, Chinese, and “Negroes” would keep their

ethnic distinctiveness, he suggested at one point, and thus use their strength

to “subjugate and dominate” the rest of the nation. Costigliola

comments, "Kennan was aware enough to confine such racist drivel to his

diary and the dinner table, where his adult children squirmed.”

Kennan’s long-held

skepticism about democracy, meanwhile, showed no signs of abating. “‘The

people’ haven’t the faintest idea what’s good for them,” he groused in 1984.

Left to themselves, “they would (and will) simply stampede into a final,

utterly disastrous, and unnecessary nuclear war.” Even if they somehow managed

to avoid that outcome, they would complete their wrecking of the environment

“as they are now enthusiastically doing.” In his 1993 book, Around the Cragged

Hill, a melancholy rumination on all that plagued modern American life, Kennan

called for the creation of a nine-member “Council of State,” an unelected body

to be chosen by the president and charged with advising him on pressing medium-

and long-term policy issues, with no interference by the hoi polloi. The idea

was half-baked at best. That American democracy was, in its essence, a messy,

fractious, pluralistic enterprise, with hard bargaining based on mutual

concessions and with noisy interest groups jockeying for influence, he never

fully grasped.

What he did

understand were diplomacy and statecraft. His body of writing, published,

unpublished, historical, and contemporaneous, stands out for its cogency,

intricacy, and fluency. He could have been more consistent; he got some things

wrong. But as a critic of the militarization of U.S. foreign policy in the Cold

War and beyond, Kennan had few, if any, peers. For he grasped realities that

have lost none of their potency in the almost two decades since his death—about

the limits of power, the certainty of unintended consequences in war-making,

about the prime importance of using good-faith diplomacy with adversaries to

advance U.S. strategic interests. Understanding the growth and projection of

American power over the past century and its proper use in this one, it may

truly be said, means understanding this “life between worlds.”

Russia’s war on Ukraine

has forced Europeans to rethink their place in the world. This violent conflict

has also created a new cold war. But, in contrast to the confrontation of the

Soviet era, in this senseless war, it is still unclear whose side many states

are on.

The outlines of this

cold war emerged around the time of NATO’s June 2022 summit in Madrid. Members

of the alliance showed remarkable unity and resolve as they decided to funnel

arms to Ukraine, increase defense spending, bolster their military deployments

in eastern Europe, and impose severe economic sanctions on Russia.

Despite this, they

need to contend with the fact that the West has lost much of its normative

power – as this author was reminded in a recent series of meetings with

politicians from Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. Western states

will struggle to convince countries in these regions to side with them in the

new cold war.

Globally, around

two-thirds of countries support Ukraine. However, they are still willing to

back sanctions on, or even multilateral declarations condemning Russia. For

instance, the BRICS states – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa –

invited 12 other countries to their recent summit. China used the opportunity

to call on them to unite to support one another’s fundamental interests. Given

the internal strains on liberal democracy, which will increase if the far right

wins the coming election in Italy – and given the ongoing international

struggle between liberal and authoritarian states – this sort of effort could

harm democracy’s normative standing in the global arena even more.

Against this

background, the Western alliance now faces three major challenges shaping the

new cold war. These challenges, which are constantly developing, involve

external partnerships, the unity of the European Union, and people power.

Western governments play a markedly different role in all three areas from

their counterparts elsewhere.

External Alliances

Many countries in

Latin America, Africa, and Asia remain traumatized by colonialism and wary of

what they see as double standards in US foreign policy. The NATO-led military

intervention in Libya only increased some of these countries’ concerns about

the Western alliance – as did the US-led withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan,

which left behind the wreckage of unfinished reform projects. Nonetheless, this

does not necessarily mean that these states have any more confidence in Russia,

China, or Turkey.

Most Latin American,

African, and Asian states are far less interested in the West’s efforts to

uphold a rules-based order than in transactional relationships that could help

them deal with domestic problems. Russian and Chinese disinformation, cheap

Russian energy, and accessible Chinese loans and infrastructure projects can be

far more appealing than what the West appears to offer.

The EU must therefore

consider how it approaches its international engagement and seeks to offer real

alternatives to Russian and Chinese strategies. To secure its geopolitical

position, the EU should establish strong links to emerging markets, investing

significantly in their local private sectors and enabling them to enter the

global supply chain. Focusing on energy, a green economy, and intelligent

infrastructure would help present a forward-looking and future-orientated

commitment to partner countries. This is something that China lacks. Mobilizing

funds that can practically rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative and

strategically channel them throughout Africa and Asia is challenging, as it

would require enhanced consensus among EU member states. However, if

implemented quickly and efficiently, the EU’s Global Gateway infrastructure

investment program would be a geopolitically significant project for EU

engagement with external actors.

EU Unity

Recent statements by

various EU and NATO leaders suggest significant differences regarding the peace

negotiations between Russia and Ukraine. Crucially, NATO member Turkey has

engaged in behavior similar to Russia’s – invading and annexing the territory

of independent countries (Cyprus and Syria), calling into question its border

with a neighboring state (Greece), shifting towards authoritarianism, and

committing widespread human rights violations at home.

Just as the Russian

president invokes Peter the Great and dreams of the Russian Empire, his Turkish

counterpart invokes Suleiman the Magnificent and the Ottoman Empire. While the

United States and many EU countries may have often ignored this problem, there

is still a risk that Turkey’s revisionism could threaten the unity of the

Western coalition. The EU should acknowledge that the assertiveness of Turkish

foreign policy is a challenge to regional stability and adjust its Turkey

policy accordingly. Adopting a transactional relationship framework and

developing some interdependence on select bilateral issues would be a first but

politically important step towards increasing the EU’s negotiating power with

the country.

People Power

Many Western

countries will soon hold elections against the backdrop of multiple crises.

Most of their citizens want to support Ukraine. Still, they are also weary of

long-running economic and public health problems and the widespread sense of

insecurity in Europe. All this could affect their attitudes towards the new

cold war and solidarity within the Western alliance.

The situation could

deteriorate this winter as further rises in energy prices contribute to

political instability and social tensions. It is unclear whether, in these

circumstances, citizens will continue to support increases in defense spending

or maintain a hard line on Russia. In some Western countries, a culture of

individualism and reluctance to make even small sacrifices for the greater good

could lead to a significant shift in foreign policy.

The situation could

deteriorate in winter, as further rises in energy prices contribute to

political instability and social tensions

In the long run,

democracy is the most powerful and effective governance system available. But,

in the coming months, Western states will have work to do if they are to

convince their partners elsewhere in the world of this fact. Democracy is on

the defensive, and the reasons for this are pretty clear. If the West wants to

convince of the power of its governance system, it should first fix its

problems and then create an exportable grand narrative.

The two most

important priorities towards this end are: firstly, to fix inequities, so that

shared prosperity is guaranteed; and secondly, to revitalize the Western

security order to guarantee peace and stability on our soil. The Western

alliance will need to deal with the mounting domestic challenges its members

face if they maintain their alliance's unity and help defend Ukraine. In this

respect, they will need to find a way to bring peace to Ukraine while expanding

democracy in a world where democracy’s enemies are gaining ground. The recent

Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit was a golden

moment for the world's united authoritarians–whether they are anti-NATO forces

or an economic coercion machine, we should all beware. Anne Applebaum is

perhaps right: the bad guys are winning. We must make sure that any such

victory is short-lived.

Losing Ground

While the early 2000s

witnessed the U.S.-led “global war on terror” and militant Islamist

expansionism, liberal democracy and market capitalism continued their march.

Yet over the past decade, democracy and capitalism have come under stress. In

many places, the promise of freedom and prosperity has fallen short. Capital

and wealth have increasingly accumulated in the hands of a few, while certain

liberties have led to societal divisiveness and polarization. Democratization

has suffered from a rollback, giving way to resurgent authoritarianism in many

countries.

The dissolution of

the Union under

Mikhail Gorbachev appeared to set the stage for a “unipolar moment” for the

U.S. to reshape the world in its own image.

As citizens became

more disillusioned with the disappointing results of democracy and capitalism,

exacerbated by globalization and technological advancement, many sought

alternatives. Populism and authoritarian varieties of governance attracted

those resentful of being left behind financially. Populist leaders connected

directly with the masses and bypass established centers of power such as the

media and entrenched political classes – pitting the masses against the elites

and weakening the social and political fabric of democratic, capitalist

societies.

Enter China. Its

allure thrives on the shortcomings of democracy and capitalism. Its model of

top-down “authoritarian capitalism” is still Marxist-Leninist, but with a

twist: its “democracy” is limited to inside the Chinese Communist Party (CCP),

comprising a single-party state rather than a multiparty democracy as in the

West. China exhibits centralized political control in a totalitarian fashion,

yet its economic development and management are market-consistent, if not

market-driven as such. China thus frustrates the Western model of liberal

democracy and the market capitalism in novel ways.

China’s Challenge

The ideological

battle that Marx started did not end with the Soviet demise but continued with

China’s rise and resurgence. Having just celebrated the CCP’s 100th year,

communism is alive and well in China, but with capitalist characteristics. The

inherent contradictions of political totalitarianism and market capitalism make

China simultaneously strong and weak. No other modern state has been able to

have its cake and eat it, too: imposing centralized political control at the

expense of rights and freedoms while running an economy that delivers better

lives and standards of living for its people.

The CCP-ruled Chinese

state leads and drives a capitalist economy like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan

pioneered in the 1960s-1980s. The difference is that these three Asian

countries were strong U.S. allies, irreversibly becoming Western-style

democracies; China is not, and never will be. In this way, China is trying to

steer away from the West’s flaws of concentrated wealth, political

polarization, and societal dysfunction.

The Soviets lost without a real fight; the Chinese are

likely to put up one, because they will not accept losing.

Moving forward,

China’s approach to being a superpower is likely to reshape the global

system to its preferences. The new Cold War is, structurally, age-old: it

continues the previous confrontation of the last century with a new chapter.

Then, the Soviet Union confronted the U.S. directly in proxy battlegrounds in

the developing world but eventually lost because it could not keep up with the

more dynamic Western-centric capitalist development. The Soviets did not lose

militarily but economically.

On the other hand,

China has not been confronting the U.S. directly in military terms, despite its

huge arms buildup. China’s direct and aggressive pushback takes place on trade

protectionism and technological innovation. This face-off between the new and

old East (China and Russia), on the one hand, and the old West, on the other,

would in the best-case scenario, be solved through compromise.

That would see China

accorded a role befitting its global weight and pride and Russia retaining

commensurate imperial dignity and security guarantees from an expansionist

European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. China and Russia

will likely feel resentful and agitated if denied and suppressed. The Soviets

lost without a real fight; the Chinese are likely to put up one, and with

Russia at their side, because they will not accept losing.

Scenarios

Round two of this old

Cold War with new characteristics can lead to three potential outcomes. First,

if the U.S.-led and Western-centric alliance system fails to accommodate China,

tensions will likely intensify and lead toward confrontation and conflict.

While China’s intimidation and threats against Taiwanese autonomy is a major

potential flash point, Beijing’s maneuvers in the South China Sea – where it

has staked out rocks and reefs and turned them into militarized islands – will

continue to threaten the security and economic interests of the Philippines and

Vietnam, U.S. allies and strategic partners, respectively. Tensions over

China’s high-tech innovation and acquisition and its rising protectionism may

also spill from geoeconomic competition to outright military confrontation.

Instead of conflict,

the U.S. and China could also arrive at mutual respect and accommodation. This

second scenario is premised on China’s power projection within its sphere of

influence under the Belt and Road Initiative, covering much of the Eurasian landmass up to

Russia’s strongholds and parts of Africa. This would be a so-called “G-2”

setup. A decade ago, most countries feared G-2 because it would virtually

divide the globe into two main geostrategic swathes under the two superpowers.

But as confrontation and conflict loom, such an arrangement may again find

appeal.

The third scenario is

attrition between the U.S. and China. While their geostrategic rivalry and

competition continue to heat up, it remains manageable, with off-ramps and

reciprocal, timely backdowns from both sides. The two superpowers would

maintain their seesaw competition, reinforced by economic interdependence and

nuclear deterrence on each side, without degenerating into military conflict.

While the second and third scenarios are

universally beneficial, confrontation and conflict first outcome would fit past

interstate relations patterns. It is not just the repeat of history that beset

the U.S.-China rivalry. More to blame is the structure of an international

system dominated by inherently distrustful nation-states, in which only one can

be at the top.

For updates click hompage here