By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Arsonist, Killer, Saboteur, Spy

In late January,

barely a week into Donald Trump’s second term, a senior NATO official told members

of the European Parliament that Russia’s intensifying use of hybrid warfare

poses a major threat to the West. In the hearing, James Appathurai,

NATO deputy assistant secretary-general for innovation, hybrid, and cyber,

described “incidents of sabotage taking place across NATO countries throughout

the last couple of years,” including train derailments, arson, attacks on

infrastructure, and even assassination plots against leading industrialists.

Since Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale war in Ukraine

in 2022, sabotage operations linked to Russian intelligence have been recorded

in 15 countries. Speaking to the press after the January hearing, Appathurai said it was time for NATO to move to a “war

footing” to deal with these escalating attacks.

In the weeks since

then, Trump’s dramatic overtures to Putin have pushed the sabotage campaign

into the background. Instead, in aiming to quickly secure a deal with Russia to

end the war in Ukraine, the Trump administration has talked of a new era of relations

between Washington and Moscow. At the same time, the White House has taken

steps to dismantle efforts within the FBI and the Department of Homeland

Security to counter cyberwarfare, disinformation, and election interference

against the United States—all of which have previously been tied to Moscow.

Indeed, Trump has suggested that Russia can be trusted to uphold any peace deal and that Putin is “going to be more generous than he

has to be.”

But any assumption

that a Trump-Putin deal will cause the Kremlin’s spies and saboteurs to step

back is dangerously mistaken. For one thing, their political masters would not

allow it. Very few in Moscow’s security establishment believe that a durable peace

can be achieved with the United States or the broader West. In February, Fyodor

Lukyanov, head of research at the Valdai Club, a pro-Kremlin think tank, said

that there was no chance for a “second Yalta”—a global deal that would redefine

the borders and spheres of influence in Europe. And Dmitry Suslov, another

prominent voice of Kremlin foreign policy, has said that any thaw in

U.S.-Russian relations would be short-lived and unlikely to survive the U.S.

midterm elections in 2026.

At the same time, in

Russia’s security services, mistrust of American intentions runs deep. For

centuries, Russia has viewed the West as intent on Russia’s subjugation or

outright destruction, and Soviet and Russian intelligence services have

operated for decades on the assumption that the West is an implacable foe. To

Moscow’s spies, Trump’s courting of Putin has provided an opportunity to expand

and strengthen their subversion campaign in Europe. Given the Trump

administration’s skepticism toward NATO and the defense of its transatlantic

allies, a U.S.-Russian agreement could increase Moscow’s

willingness to launch unconventional attacks in Europe.

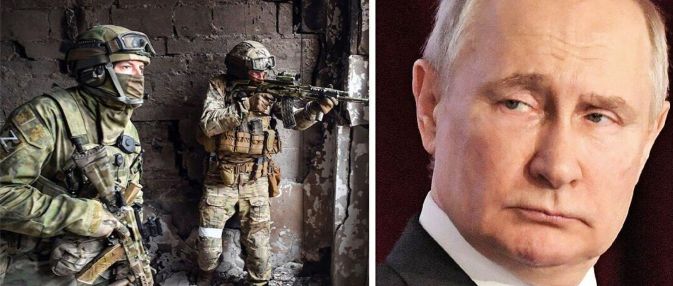

Russian President Vladimir Putin, Moscow, March 2025

After three years of

full-scale war in Ukraine, Russia’s spy agencies are now fully mobilized in

Europe and have built sabotage and hybrid warfare into a comprehensive

strategy. These attacks are not merely designed to keep European governments

off-kilter. They also aim to diminish Europeans’ support for Ukraine by raising

costs on the governments and industries in ways that are not easy to counter,

harassing the population, and seeking vulnerabilities in European defense.

Unless the West is prepared to develop a cohesive strategy to counter those

attacks with a signal strong enough to serve as an effective deterrent, Moscow

will see little downside to accelerating this campaign in any post-deal future.

Moscow’s New Killers

Ever since Russia’s

annexation of Crimea in 2014, Moscow’s spy agencies have been experimenting

with sabotage operations abroad as a way to pressure

the West. At first, this included occasional attacks, such as the blowing up,

by agents of Russia’s GRU military intelligence agency, of ammunition depots in

the Czech Republic that had been supplying Ukrainian forces then fighting

Russia in the Donbas. After its 2022 invasion of Ukraine stalled, Moscow was at

first cut off from the West, with its diplomats expelled and its spies forced

to regroup. But in 2023, its intelligence services, including the Federal

Security Service, or FSB, the Foreign Intelligence Service, or SVR, and the

GRU, began redeploying in Europe in what became a new kind of hybrid warfare campaign.

So far, the most

brazen operation was Russia’s attempted assassination in the spring of 2024 of

Armin Papperger, the head of Rheinmetall, Germany’s

largest arms manufacturer. The plot was thwarted by German and American

intelligence services, as Appathurai, the NATO hybrid

warfare official, publicly confirmed in January. In his testimony, Appathurai noted that there have been “other plots” against

European industry leaders, as well. This threat seems unlikely to go away:

notably, along with other European defense companies, Rheinmetall is likely to

play an even larger role in arming Ukraine in a post-deal future, and its

growth projections have surged since the Trump administration has come to

power.

A shopping Center after a Russia-linked arson attack,

Warsaw, May 2024

In his January

testimony, Appathurai also confirmed that Russia has

been recruiting “criminal gangs or unwitting youth or migrants” to

conduct many of these operations. In March 2024, for example, two British men

were arrested for setting fire to a Ukrainian-linked parcel delivery warehouse

in east London—an attack that was connected to the Wagner paramilitary company,

traditionally a front for the Russian military intelligence agency. One reason

for this is that local criminals could be recruited via social media for

one-off jobs without even knowing who they are working for, making it more

difficult to counter, and it became harder to infiltrate Russian nationals into

these countries.

In addition to

targeting European infrastructure and military logistics, Moscow’s spy agencies

may also be seeking to use sabotage operations to influence the political

landscape in target countries. In the run-up to Germany’s federal election in

February, for example, there was a series of attacks against civilians in

Germany by Afghans and other immigrants. According to a senior German

intelligence official we spoke to shortly before the election, the German

agencies believed that Russian security agents may have instigated these

attacks in order to inflate support for the far right,

which opposes German support for Ukraine.

These attacks don’t

necessarily have to be violent to be effective. For example, there are

indications that Russian agencies could use social media to recruit teenagers,

including those belonging to post-Soviet diasporas, to spray hateful slogans on

the walls of apartment buildings in neighborhoods with a significant migrant

population, threatening or humiliating locals to incite hatred against refugees

from Ukraine or Syria. These attacks don’t require much preparation and may

cost only a few thousand dollars. More ambitious recruits might be paid to

undertake more violent actions, such as committing arson or throwing Molotov

cocktails.

European intelligence

officials believe that Germany, along with Poland and the UK, will remain one

of Moscow’s primary targets. Given the country’s large immigrant population

from former Soviet republics, including Russia and Ukraine, and the rising tensions

about immigration, Russia’s spy agencies may see particular potential for

influencing the political situation and public opinion. Moreover, given

incoming Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s commitment to dramatically increase German

defense spending and its role in Western security, the Kremlin may have an even

greater incentive to try to destabilize the country.

Hostage Games

Another element of

Russia’s emerging strategy is its growing use of hostages. Never

before have foreigners with European and American passports been seized

as extensively in Russia as they are now. Since the start of the invasion,

Russia’s Federal Security Service has begun arresting numerous citizens of

target countries under various pretexts—such as discovering a piece of gum with

cannabis in a purse or finding a donation of a few hundred dollars to a

Ukrainian charity on the victim’s smartphone.

During the Cold War, the

business of prisoner swaps was mostly limited to quiet exchanges between rival

Western and Soviet spy agencies that happened on the sidelines of geopolitics.

For instance, the KGB did not bring spy swaps to the Strategic Arms Limitation

Talks (SALT) between U.S. President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid

Brezhnev. Since the war in Ukraine began, that has changed. Following the

negotiations over the release of detained American basketball star Brittney

Griner, Russian intelligence agencies—especially the SVR and the FSB—have

recognized that hostage trades can powerfully affect public opinion in target

countries. As a result, Moscow has turned captured foreigners, including from

France and Germany as well as the United States, into a substantial form of

leverage in geopolitical negotiations.

Now, the role of

Russia’s spy agencies in capturing and trading hostages is becoming

institutionalized. The FSB emerged as a backchannel between the United States

and Russia several years ago, so it is no surprise that it played a major role

in talks for the release of American journalist Evan Gershkovich in 2024.

Indeed, Sergei Naryshkin, the head of the SVR, has been involved in such

negotiations with Washington for quite some time, including in 2022, when then

CIA director William Burns met Naryshkin in Ankara. Among the items on the

agenda for that meeting, alongside the use of nuclear weapons, was the issue of

U.S. prisoners in Russia.

More recently, when

Kremlin officials held preliminary talks with Trump administration officials in

Riyadh about a Ukraine deal, Naryshkin was included on the Russian side,

presumably, among other things, to make use of the hostage issue. Notably,

those talks were preceded by the release of American teacher Marc Fogel, who

had been detained in Russia for possessing medical cannabis; in a public

ceremony, Trump touted Fogel’s return and greeted him at the White House.

Indeed, hostage swaps draw on some of the quid-pro-quo dynamics that Trump

prefers in his approach to dealmaking, making it all the more

likely that Russia will continue to accumulate Western prisoners. On March 11,

Naryshkin had his first phone conversation with Trump’s CIA director, John

Ratliff, and according to Russia’s state news agency, TASS, the two agreed to

“maintain a regular contact.”

More Darkness, More Deception

Since 2022, Russia’s

intelligence agencies have also linked the sabotage option firmly with their

more long-standing campaign of transnational repression. The Kremlin has a very

long tradition of using various tools against its enemies and opposition members

in exile, often in the same countries where it is now practicing sabotage,

including Germany, the UK, and the Baltic countries. Russia’s secret police may

have the dubious honor of having invented transnational repression: beginning

in the second half of the nineteenth century, tsarist secret police infiltrated

and harassed Russian political émigrés in France and Switzerland. Their Soviet

successors significantly escalated those tactics, up to and including political

assassinations. Since the early years of this century, Putin’s spies have done

the same, attacking opposition figures who have sought refuge abroad.

But now Russia’s

transnational repression is becoming more sophisticated and often involves

efforts to deflect blame toward other parties. In early February, for example,

the SVR publicly accused Ukraine’s intelligence agencies of “preparing attacks”

against Russian opposition or business figures who have sought refuge abroad.

The SVR asserted that the would-be attackers, in the event of arrest, would

“blame the Russian special services, allegedly on whose orders these attacks

were prepared.”

The Russian exile

communities across Europe quickly grasped the significance of this

announcement: the SVR was laying the groundwork for a new round of attacks on

Russian exiles, with the blame being placed on Ukraine

in advance. Moscow’s practice of blaming Ukraine for Russian operations in the

West seems only likely to expand. From now on, these attacks, including

assassination attempts, arson, and attacks on infrastructure, will likely be

blamed on Ukrainian intelligence in an effort to turn

European public opinion against Ukraine.

Putin with intelligence chiefs after a prisoner

exchange, Moscow, August 2024

These efforts suggest

a change in Russian strategy. For several years after 2016, Moscow’s

intelligence agents seemed to be increasingly brazen and sloppy, as if they did

not really care about being exposed or caught. Consider the Russian assassin on

a bicycle who shot a Chechen separatist in the center of Berlin in broad

daylight and was almost immediately arrested by German police while he was

dumping his pistol and his bike in the nearby river Spree. To some extent,

Russian operatives like him didn’t care: they were determined to show, by their

brazen actions, that Western efforts to expose and criminally charge them were

not working.

Now, however, the spy

agencies are switching back to a more secretive mode. The war in Ukraine has

made it harder for Russians to set up their own operations in Europe, and the

recent changes in spy tradecraft—such as outsourcing operations to European nationals

for one-off jobs, out of the established spy networks in the target

countries—have helped them get around this.

In his notes he had

smuggled from Moscow, KGB archivist and defector Vasili Mitrokhin described the

Soviets’ meticulous preparations in the 1960s for a sabotage attack on the NATO

Integrated Air Defense site on Mount Parnitha, near Athens. The chosen method

for disabling it was arson using technical devices developed by the KGB’s “F”

Service laboratory. These devices were disguised as Greek-style cigarette

packs, containing highly flammable charges that could be ignited at any time

using built-in mechanisms, accounting for the rarefied air. The operation would

require, of course, several highly trained special forces operators. If this

attack ever took place, it would have been difficult not to attribute it to a

hostile state.

This was the same

model used by Putin during his early years in power. In the first decade of

this century, when Russian spy agencies carried out assassinations abroad,

those attacks had an obvious Russian state signature, as when the attackers used polonium, or the military-grade nerve agent

Novichok. But this is no longer the case. Most of the sabotage operations the

Kremlin has launched over the past two years lack direct traces to Russia. Many

also involve local perpetrators who have been recruited via social media for

one-off jobs for a few hundred dollars.

Turning a Blind Eye

Despite overwhelming

evidence that the Kremlin has developed a systematic and increasingly lethal

hybrid warfare strategy, Western leaders have failed to devise an adequate

strategy for containing it. For now, the naming and shaming tactics that the

United States and its European allies adopted after Russia’s interference in

the 2016 U.S. election remain a significant part of the Western response.

In November 2024, a

London court put on trial a group of Bulgarians who had been charged with

spying for Russian agencies—including surveilling the U.S. military base in

Stuttgart where the Ukrainian military was believed to be trained, planning an

attack at the Kazakh embassy in London, and attacking two investigative

journalists opposing the Kremlin, as well as a Kazakh politician in exile in

London. In early March, the defendants were all found guilty in what has become

a larger effort to expose and punish those who collude with Moscow. Some

European countries also seem to be attempting to reduce the effect of sabotage

attacks carried out by Russian agents, by denying or downplaying their scale.

Protesting in front of the U.S. embassy, Kyiv, March

2025

More promising are

recent efforts to double down on security. Several European countries, for

example, have taken new measures to protect telecommunication cables,

pipelines, and other critical infrastructure in the Baltics, near Russia. This

includes the launch in January of a British-led reaction system to track

potential threats to undersea infrastructure and to monitor the Russian shadow

fleet—aging and poorly maintained vessels operating with flags of convenience

and murky ownership and management—as part of the ten-nation-strong Joint

Expeditionary Force.

But the turmoil

within the U.S. intelligence community caused by Trump’s reorientation toward

Moscow has made it more difficult to shape a comprehensive Western response.

Public reports of the Trump administration’s buyout offer to members of the CIA

have been met with glee in Russia. Meanwhile, the administration has set new

priorities for U.S. intelligence—including targeting drug cartels in Mexico and

focusing more on China—rather than on Russia and support for Ukraine. For

Moscow’s spy agencies, these moves could be exploited as opportunities to

increase their activities in the West.

If Trump’s moves lead

to a dramatic decline in surveilling Russia, it will not be the first time the

U.S. intelligence community will have taken its eye off the ball. In the 1990s,

after the end of the Cold War, there was a similar shift in attention away from

Russia, one that resulted in a significant loss of expertise in Russian affairs

and an underestimation of risks on the part of Washington. This intelligence decline very likely contributed to the West’s misjudging of

Putin during his early years in power, when he laid the foundations for renewed

Russian autocracy and confrontation with Europe and the United States. It would

be disastrous to repeat the same mistake today.

For updates click hompage here