By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Rafah Operation

Palestinians are

fleeing parts of Rafah ahead of an anticipated Israeli operation in the

southern Gazan city that may weaken Hamas' brigades, but not necessarily its leadership,

according to one regional expert.

The Institute for the

Study of War (ISW) said Hamas leaders have probably calculated that the

organization can survive the operation and pursue its ceasefire demands without

major concessions "because it continues to operate from and control

another territory in the Gaza Strip outside of Rafah."

Hamas leaders have likely calculated that their

organization will endure even if Israel launches a major ground incursion into Rafah in the

southern Gaza Strip, where four of the terror group’s operational battalions

are believed to be operating.

On May 6, to

forestall an all-but-certain Israeli operation in Rafah, Hamas leaders said

that they might be prepared to accept a hostage-for-prisoners agreement with

Israel. Coming after weeks of stonewalling by Hamas, the announcement raised

hopes in Washington that some kind of deal might still be reached that could

free dozens of hostages and bring about a pause in Israel’s offensive in the

Gaza Strip. But even now, it remained unclear how committed Hamas was to

carrying out this deal, or whether it was simply seeking a means to preserve

its Rafah stronghold, where Israel believes its remaining brigades and

Gaza-based leadership are holed up.

After seven months of

war in Gaza, the Israel-Hamas conflict has caused

untold devastation to the more than two million Gazans that Hamas claims to

represent and has all but destroyed Hamas’s governance project in the strip. It

is worth asking two basic questions: What are Hamas’s goals? And what is its

strategy for achieving them?

With its heinous

October 7 assault on Israel, Hamas sought to put

itself and the Palestinian issue back at the center of the international

agenda, even if that meant destroying much of Gaza itself. The attack was also

meant to thwart a possible normalization pact between Israel and Saudi Arabia

that would promote Palestinian moderates and sideline Hamas.

But Hamas’s leaders

also have political aims that may at first seem

counterintuitive. They are trying to relieve themselves of the sole

burden of governing the Gaza Strip, which had become an impediment to achieving

the group’s goal of destroying Israel. And as talks hosted by China in early

May between Hamas and Fatah officials have underscored, the Hamas

leadership is also trying to jump-start a process of reconciliation with Fatah

and the Palestinian Authority (PA), which Fatah controls, despite years of

fierce hostility between the two groups.

Those goals, in turn,

serve a deeper purpose. In seeking to force a new governance structure on Gaza

and to refashion the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in its image,

Hamas hopes to impose a Hezbollah model on the territory. Like Hezbollah, the heavily

armed, Iranian-backed Shiite militant movement in Lebanon, Hamas wants a future

in which it is both a part of, and apart from, whatever Palestinian governance

structure next emerges in Gaza. That way, as with Hezbollah in Lebanon, it

hopes to wield political and military dominance in Gaza and ultimately the West

Bank without bearing any of the accountability that comes from ruling alone. To

understand this larger Hamas project and its important implications for Israel

and the region, it is necessary to examine the evolution of Hamas in the years

leading up to the October 7 attack and what Hamas hoped to achieve by murdering

and kidnapping scores of Israeli civilians.

Changing The Equation

Four days after

October 7, a Hamas official publicly acknowledged that the group had been

secretly planning the attack for more than two years. After a brief war with

Israel in May 2021, Hamas leaders reassessed their fundamental aims. At that

point, they had ruled the Gaza Strip for 14 years—having seized full control

from the PA in 2007, two years after an Israeli withdrawal—and could have

continued to maintain the status quo. Notwithstanding intermittent skirmishes

with Israel, Hamas was firmly ensconced in Gaza and sustained by hundreds of

millions of dollars in aid from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for

Palestine Refugees in the Near East, or UNRWA, and in funds from Qatar to cover

public salaries.

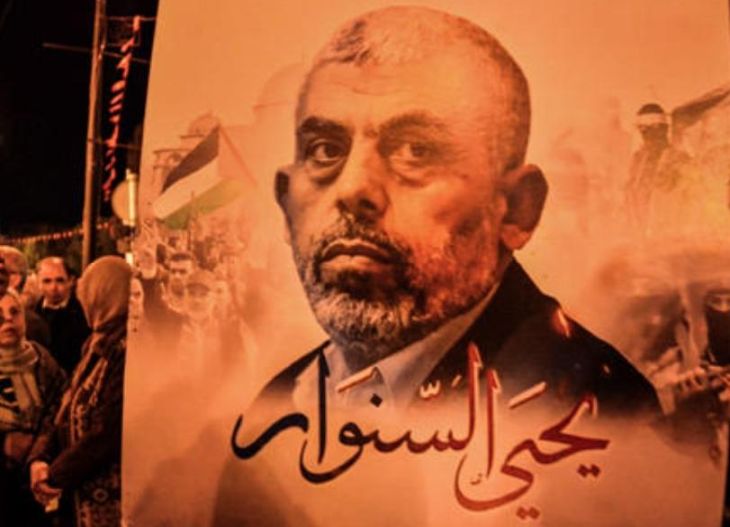

But shortly after the

2021 war, Hamas’s leader in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, presented Israel with what he

described as two alternative outcomes. In an appearance on Al Jazeera, the

Qatari-funded satellite network, Sinwar stressed that Hamas continued to aim for

the “eradication” of Israel but that he was amenable to entering a long-term

truce with the country—provided that Israel agreed to a laundry list of

demands, including dismantling all settlements, releasing Palestinian

prisoners, and allowing a Palestinian right of return. But any such truce, he

said, would be temporary and driven by the imperative of achieving unity among

Palestinian factions, presumably meaning support for Hamas’ position of

ultimately eradicating Israel.

Sinwar also boasted

that Hamas was already in contact with its “brothers in Lebanon” (Hezbollah)

and with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and suggested that these

allies would have supported Hamas in the 2021 war if it had intensified. Soon,

Hamas began meeting regularly with officials from Iran and Hezbollah. Four

months later, Hamas also sponsored a conference in Gaza hosted by Sinwar

himself that was devoted to plans for the “liberation of Palestine” once Israel

“disappears.” The conference called for replacing the PLO with a new Council

for the Liberation of Palestine that would include “all Palestinian and Arab

forces who endorse the idea of liberating Palestine, with the backing of

friendly forces.”

At the same time,

instead of prioritizing its governance project in the Gaza Strip, Hamas began

to secretly put in play a long-held but still notional plan to launch a ground

assault on Israel and initiate what it hoped would be a chain reaction that would

lead to the destruction of Israel. The group’s leaders pretended to be focused

on governing Gaza and addressing the needs of Palestinians living there, while

they were stockpiling small arms and, as a Hamas official named Khalil al-Hayya

later conceded, “preparing for this big attack.” Ultimately, as al-Hayya put

it, Hamas concluded that it needed to “change the entire equation” with Israel.

Now Or Never

With planning for the

October 7 attack already well underway, Hamas leaders became increasingly

convinced of the urgency of doing something drastic. First, the movement’s

support in Gaza appeared to be eroding. Israel’s pre-October 7 strategy toward

Hamas was based on buying calm by allowing Qatari funds to flow into Gaza in

the hopes that this would decrease support for Hamas militancy among the Gazan

population.

For all the criticism

Israel has faced for this approach in the months since Hamas’s attack, there is

some indication that it was working. Polling conducted in July 2023 by the

Palestinian Center for Public Opinion, for example, revealed that 72 percent of

Gazans agreed that “Hamas has been unable to improve the lives of Palestinians

in Gaza” and that 70 percent supported the proposal that Hamas’s rival, the PA,

take over security in Gaza. Looking at these numbers, Hamas could only have

concluded that its governance project in Gaza was floundering.

Hamas also feared

Israeli normalization with Saudi Arabia. The Saudis were demanding that Israel

take tangible and irreversible steps toward a two-state solution and that

Washington enter into a formal security treaty with Riyadh; in exchange, the

Saudis would formally recognize Israel. Most Palestinians likely saw progress

on Palestinian statehood as a good thing, but not Hamas, which has always been

dead set against a two-state solution and committed to Israel’s destruction.

Hamas also understood that under a two-state solution, both sides would be

expected to clamp down on their respective violent extremists, which would not

bode well for Hamas and its allies.

At the same time,

Hamas likely saw prolonged instability in Israel as a golden opportunity.

Alongside rising violence in the West Bank and clashes between Palestinian

worshipers and Israeli security forces at Jerusalem’s al Aqsa mosque,

Netanyahu’s right-wing government had faced months of protests over its

proposed judicial reforms. The heightened tensions in the West Bank—driven in

part by the efforts of Hamas’s external leaders, such as Salah al-Arouri, to

instigate attacks against Israelis—the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) had moved

more resources there, leaving the Gazan border more vulnerable.

It was amid these

developments that Hamas decided to launch its October 7 attack. Harking back to

Sinwar’s 2021 conference, in which he had threatened to respond to actions that

Hamas perceived as undermining Palestinian claims to Jerusalem, Hamas called

the October 7 operation the Al Aqsa Flood.

“We Need This Blood”

From the outset of

its planning, Hamas anticipated that its invasion of southern Israel would draw

Israel into a larger conflict, one that it hoped Hezbollah and other members of

Iran’s “axis of resistance” would quickly join. (It is now understood that Hamas

kept the precise details of its attack, including the exact date, closely held,

but Iran and Hezbollah were aware of the general concept.) Hamas leaders also

planned for the possibility that the attack could achieve more, including a

scenario in which Gazan-based Hamas militants would link up with fighters in

the West Bank and follow up on the initial assault by targeting Israeli cities

and military bases. To this end, when they broke out of Gaza on October 7,

Hamas militants were carrying enough food and gear to last several days.

Israeli forces

ultimately disrupted those maximalist plans, but before they could regain

control of the border areas around Gaza, the Hamas attackers committed horrific

atrocities, murdering around 1,200 Israelis and foreign nationals, taking more

than 200 hostages, and recording and broadcasting their crimes. Hamas even used

stolen phones to hijack victims’ social media and WhatsApp accounts, from which

it livestreamed attacks, issued threats to victims’ families, and called for

further acts of violence. Israeli forces later found documents on the bodies of

slain Hamas attackers instructing them to “kill as many people as possible” and

“capture hostages.” One document specifically directed operatives to target

children at an elementary school and a youth center.

In orchestrating and

sensationalizing this mayhem, Hamas sought to provoke Israel into a major land

invasion of Gaza. A core pillar of this strategy was to start a war that would

cause high numbers of Palestinian casualties, as Hamas’s political leader in

Doha, Ismail Haniyeh, bluntly confirmed in a video address days after October

7: “We are the ones who need this blood, so it awakens within us the

revolutionary spirit, so it awakens within us resolve, so it awakens with us

the spirit of challenge and [pushes us] to move forward.”

It was not by

accident that Hamas built more than 300 miles of tunnels in Gaza to protect its

fighters but not a single bomb shelter to protect Palestinian civilians. Hamas

knew full well that the Israeli response would lead to civilian Palestinian

casualties—and that it would also end the Hamas governance project in Gaza, a

responsibility that the group was eager to relinquish.

Catastrophic Success

Despite its own

maximalist aspirations to reach Tel Aviv and connect with fellow militants in

Hebron, Hamas appears to have been unprepared for its initial success on

October 7. Hamas was able to get far more of its fighters into Israel than it

had expected, having anticipated that Israeli security systems and forces would

kill and capture more attackers along the border than they did. Moreover, two

additional waves of attackers followed as news spread in Gaza that Hamas had

breached the border fence. The first included members of other terrorist groups

such as Palestinian Islamic Jihad and the Popular Front for the Liberation of

Palestine; the second included unaffiliated Gazans, many of whom killed,

kidnapped, and carried out other atrocities in Israeli communities near the

border.

Although the attack

went unchecked for hours, and it took Israeli forces days to apprehend or kill

all the attackers and regain control of the border, it did not produce several

of Hamas’s hoped-for outcomes. For one thing, Israel did not immediately launch

a land war in Gaza, in which Hamas thought it would have a major advantage

because of its tunnel network. Instead, Israel took a couple of weeks to plan

its response, which started with a punishing air offensive followed weeks later

by a combined air and ground offensive aimed at uprooting the military

infrastructure Hamas had built within and under civilian communities.

Nor did Hezbollah and

other members of the axis of resistance launch a full-scale attack on Israel.

When Iran carried out a major attack in April in response to an Israeli strike

on senior Iranian commanders in Syria, Israeli and allied air defenses largely

neutralized what proved to be a one-off operation. Both Hezbollah and Iran,

Hamas’s most powerful allies, were keen to join the fight, but neither wanted a

full-scale war.

In short, the

Israel-Hamas war has been devastating, but it has not set off a regional war

that threatens Israel’s survival—and Hamas is fine with that, for now. For

Hamas, strategic patience is a virtue. Although the group planned for the

possibility of still greater success, its primary goal was to initiate a longer

and inexorable process leading to Israel’s destruction. To do that, Hamas

needed to get out from under the burden of governing the Gaza Strip, which it

had concluded was undermining rather than enabling its attacks on Israel. Freed

of that responsibility, Hamas could now pledge “to repeat the October 7 attack,

time and again, until Israel is annihilated.”

The Hezbollah Model

In launching the

October 7 attack, Hamas upended the status quo in Gaza. Less noted has been

what it wants instead. As debate ensues over the postwar administration of the

strip, Hamas has begun to lay the groundwork for reconciling with and

ultimately taking over the PLO, thereby guaranteeing that it is part of

whatever governance structure emerges. Al-Hayya, the Hamas official who

explained that his group wanted to change the whole equation, recently

acknowledged this plan and has floated the idea of a five-year truce with

Israel based on the armistice lines that existed before the 1967 war and on a

unified Palestinian government that controls both the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Indeed, since December, senior leaders from Hamas have been meeting with factions

of Fatah that are opposed to Mahmoud Abbas, the deeply unpopular leader of the

PA, to discuss just such a rapprochement. On April 21, Haniyeh explicitly

proposed restructuring the PLO to include all Palestinian factions.

For a militant

Islamist movement that has long disavowed the more moderate and secular

Palestinian Authority, seeking to join forces with the PLO may seem surprising.

But behind Hamas’s recent push is the more important strategic goal of

emulating the Hezbollah model. In Lebanon, Hezbollah is nominally part of the

weak Lebanese state, allowing it to influence policy and have at least some say

in directing government funds, yet it maintains complete autonomy in running

its own powerful military and in fighting Israel. Under a new arrangement for

Gaza and the West Bank, Hamas hopes to exert the same influence and

independence with its own movement and militia, neither beholden to nor

controlled by a government.

Hamas’s leaders in

Gaza looked to Hezbollah for guidance as they planned the October 7 attack,

which came straight out of Hezbollah’s playbook. Although Hamas’s external

leadership in Qatar, Turkey, and Lebanon has been more interested in bringing

the war to a close, Sinwar—who holds most of the cards by being on the ground

in Gaza and controlling the Israeli hostages—is fixated on absorbing Israel’s

hits, surviving, and declaring “divine victory.” He is looking to the 2006 war

with Israel, in which Hezbollah became the first Arab army not to be destroyed

by the IDF, despite heavy losses, and enjoyed a significant boost to its

regional stature as a result. Surviving the Israeli military offensive, Sinwar

appears to have calculated, would position him well for a senior position in a

future Palestinian government.

Of course, the idea

that Sinwar might have a future place in a Palestinian unity government is

preposterous, and not only because of the heinous nature of what Hamas did on

October 7. After all, as a longtime sworn enemy of Fatah and the PA, Hamas took

over the Gaza Strip by armed force in 2007 after a civil war with Fatah.

Moreover, the Biden administration has explicitly ruled out any postwar

governance structure that includes Hamas. But without a concerted effort to

fully dismantle the group’s political infrastructure in Gaza and build

alternatives, Hamas may yet succeed in positioning itself to be one of several

parties in control when the fighting stops.

Should that happen,

Hamas might well adopt other aspects of the Hezbollah approach. Just as

Hezbollah has used its haven in Lebanon to launch cross-border attacks on

Israel as terrorist plots against Israelis and Jews around the world, Hamas

could expand its military operations beyond the borders of Israel, the West

Bank, and the Gaza Strip and carry out plausibly deniable terrorist attacks

abroad. So far, Hamas has never carried out an international terrorist

attack—though it has come close on several occasions. But since October 7,

European intelligence agencies have discovered Hamas plots in Germany and

Sweden as well as logistical operations in Bulgaria, Denmark, and the

Netherlands.

Preventing A Postwar Victory

Notwithstanding

Hamas’s belated announcement in early May that it might approve some version of

a hostage-for-prisoners deal, Biden administration officials have long blamed

Hamas’s leadership for prolonging the war by not releasing the Israeli hostages

and laying down arms. But they are not the only ones. There are indications

that Gazans themselves, increasingly desperate after nearly seven months of

devastating war, are losing patience with the movement and its failure to take

steps to protect them from the Israeli retaliation Hamas was determined to

provoke. “I pray every day for the death of Sinwar,” one Gazan told the Financial

Times in April. Polling by the Palestinian Center for Policy and

Survey Research suggests that over the past three months, Hamas’s popularity

has dropped by about a quarter, from 43 percent to 34 percent. “Almost everyone

around me shares the same thoughts,” a freelance journalist in Gaza told The Washington

Post recently. “We want this waterfall of blood to stop.”

Hunkered down in

their underground tunnels, Hamas’s leaders are surely aware that the civilians

they have left unprotected aboveground are growing increasingly angry at the

movement, which may account for the more moderate tone of some statements the

movement’s leaders have recently released. But they are wary of agreeing to any

swap of hostages for prisoners that does not come with a complete cease-fire

and save the remaining Hamas battalions in Rafah. Indeed, poor polling numbers

are only likely to underscore the importance of securing a position within

whatever governance structure comes next—one in which Hamas will not be the

only party ruling Gaza and therefore not the one blamed when things don’t go

well. Hamas understands that after it releases the remaining hostages, the best

leverage it will have is its remaining fighting cadre.

So as Hamas sees it,

it must first secure a Hezbollah-style victory, simply by surviving. Then, it

must adopt a Hezbollah model in its relation to the postwar governance

structure that emerges—joining with the PLO and changing the Palestinian

movement from within while maintaining Hamas as an independent fighting force.

For Hamas, this would be a return to first principles: it could pursue its

fundamental commitment to destroying Israel and replacing it with an Islamist

Palestinian state in all of what it considers historic Palestine.

To arrest this plan

before it is set in motion, it will be paramount for Israel, the United States,

and their Arab and Western allies to keep Hamas out of whatever Palestinian

governance structure is built. If they do not, the group could soon create a situation

that is far more dangerous and destabilizing than the one that allowed it to

launch the October 7 attack. The peril lies in the fact that both Hamas and

Hezbollah truly believe that Israel’s destruction is inevitable and that

October 7 is simply the beginning of an irreversible process that will

ultimately achieve just that. Anyone who truly supports the idea of securing a

durable settlement to this conflict must oppose including Hamas in Palestinian

governance for the simple reason that Hamas’ fundamental goals are incompatible

with peace.

For updates click hompage here