By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

China’s Rapid Rearmament

Amid a growing

bipartisan consensus that the United States needs to do more to contain China,

much of the policy debate in Washington has focused on China’s economic and

technological clout. Now, given China’s economic problems—high youth

unemployment, a troubled real estate market, increased government debt, an

aging society, and lower-than-expected growth—some scholars and policymakers

hope that Beijing will be forced to constrain its defense spending. Others go

so far as to say the Chinese military is overrated, contending that it will not

challenge U.S. dominance anytime soon.

However, these

assessments fail to recognize how much China’s defense industrial base is

growing. Despite the country’s current economic challenges, its defense

spending is soaring and its defense industry is on a wartime footing. Indeed,

China is rapidly developing and producing weapons systems designed to deter the

United States and, if deterrence fails, to emerge victorious in a great-power

war. China has already caught up to the United States in its ability to produce

weapons at mass and scale. In some areas, China now leads: it has become the

world’s largest shipbuilder by far, with a capacity roughly 230 times as large

as that of the United States. Between 2021 and early 2024, China’s defense

industrial base produced more than 400 modern fighter aircraft and 20 large

warships, doubled the country’s nuclear warhead inventory more than doubled its

inventory of ballistic and cruise missiles, and developed a new stealth bomber.

Over the same period, China increased its number of satellite launches by 50

percent. China now acquires weapons systems at a pace five to six times as fast

as the United States. Admiral John Aquilino, the former commander of U.S.

Indo-Pacific Command, has described this military expansion as “the most

extensive and rapid buildup since World War II.”

China is now a

military heavyweight, and the U.S. defense industrial base is failing to keep

up. When the Axis powers were advancing in Europe and Asia, President Franklin

Roosevelt mobilized that base, calling it the “arsenal of democracy.” A similar

U.S. effort is necessary today. U.S. defense production has atrophied, and the

system lacks the capacity and flexibility that would allow the U.S. military to

deter China and, if a conflict does break out, to fight and win a protracted

war in the Indo-Pacific region or a two-front war in Asia and Europe.

Washington must fix critical bottlenecks, and it must act fast if it wants to

keep pace. In short, the United States needs to commit much more attention and

resources to military readiness if it is to succeed in assembling a new arsenal

of democracy.

Standing guard on a Chinese destroyer in Qingdao,

China, April 2024

Rapid Buildup

Chinese President Xi

Jinping has made clear that developing a world-class military is central to his

aim of pursuing the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation on all fronts.” A

key part of that process is building a defense industrial base that can produce

the hardware (such as ships, aircraft, tanks, and missiles) and software (such

as technology and systems for command, control, communications, and

intelligence) that military forces need. Over the past decade, China’s

production of surface and subsurface vessels, aircraft, air defense systems,

missiles, land systems, spacecraft, and cyberweapons has made the country a

serious competitor of the United States.

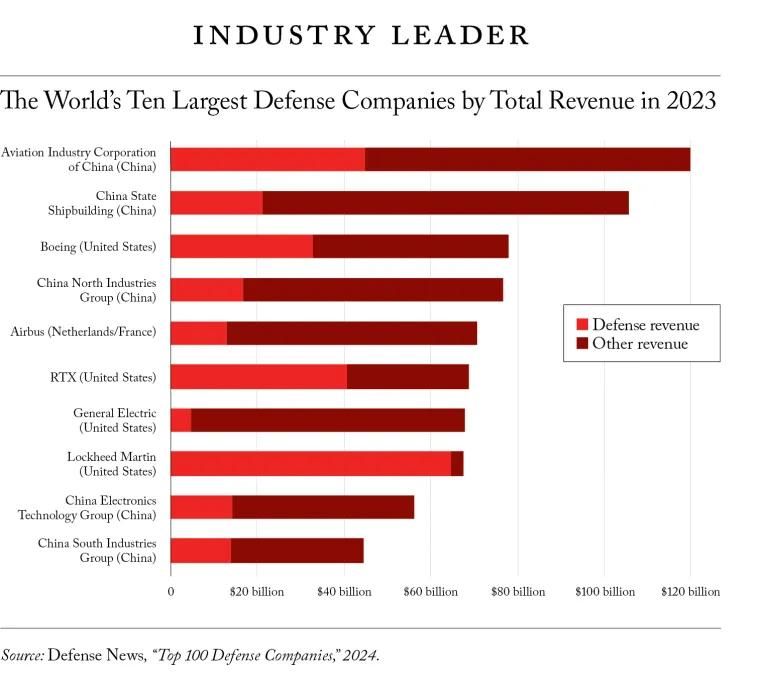

Driving this

production are China’s massive state-owned enterprises, which are charged with

developing and building the country’s weapons systems. Today, four of the

world’s top ten largest companies in combined defense and nondefense revenue

are Chinese, including the two largest: Aviation Industry Corporation of China

and China State Shipbuilding. This is a seismic change from a decade ago when

no Chinese firm cracked the world’s top 100 defense companies. Looking at

defense revenue alone, China has five companies in the global top 12, also up

from zero ten years ago. Chinese defense companies now rival such U.S. giants

as Lockheed Martin, RTX (Raytheon), Boeing, Northrop Grumman, and General

Dynamics in size and production capacity.

It is not just the

volume of defense production that is driving China’s military rise. Beijing has

also improved the research, development, and acquisition process for weapons

systems, allowing the PLA to produce advanced platforms in such complex fields

as carrier-based aviation, hypersonics, and

propulsion systems. In addition to military hardware, the PLA has built the

digital architecture that, in the event of war, would help the army coordinate

its command, control, communications, computers, cyber, intelligence,

surveillance, and reconnaissance networks and deploy firepower with the help of

artificial intelligence, big data, and other emerging technologies.

The clearest example

of Chinese military dominance is the country’s naval forces. With the country’s

vast shipbuilding capacity, the PLA Navy has become the largest in the world.

The U.S. Navy estimates that a single Chinese shipyard—such as the one on Changxing Island, located along China’s eastern coast—has

more capacity than all U.S. shipyards combined. China’s naval production now

includes everything from gas turbine and diesel engines to shipboard weapons,

electronic systems, submarines, surface combatants, and unmanned systems. In

the past decade, the PLA Navy has also made major advances in corvette

construction, built eight destroyers, and completed the aircraft carriers Shandong and Fujian.

The design of the Fujian features an electromagnetic catapult

launch system for aircraft, which allows for more comprehensive air operations,

making the carrier more capable than previous Chinese models. It can deploy up

to 70 aircraft, including fighter aircraft and antisubmarine helicopters.

Changxing Island

The PLA Navy still

trails the U.S. Navy in several areas. China has more ships than the United

States, but those it has are smaller. China has a disadvantage in firepower;

its fleet can carry roughly half as many missiles as its U.S. counterpart. The

United States also produces more advanced nuclear-powered submarines than

China. But China’s shipbuilding production would likely give it an advantage

over the United States in a protracted war, and the gap is expected to grow.

Not only do China’s commercial shipyards dwarf their U.S. counterparts, but

many of them are also used for both military and civilian construction, meaning

that China can surge its military shipbuilding capacity more readily than the

United States.

China’s defense

industry is churning out sophisticated aircraft, too. The United States still

operates the world’s largest and most advanced fleet of fifth-generation

fighter aircraft, including F-22s and F-35s. But China is catching up. Its

largest military aircraft company, the Aviation Industry Corporation of China,

produces nearly all of the country’s fighter jets, transport and training

aircraft, bombers, reconnaissance aircraft, drones, and helicopters. The

company oversees a whopping 86 laboratories and applied research centers, and

it has hundreds of subsidiaries and more than 100 overseas entities. In 2023,

Chinese companies produced well over 2,000 fourth- and fifth-generation combat

aircraft, more than doubling the 800 manufactured in 2017. Although the United

States remains ahead, producing more than 3,350 fourth- and fifth-generation

fighters in 2023, China is closing in. China is also ramping up its production

of drones, which it has used in exercises around Taiwan. China North Industries

Group, or Norinco, recently unveiled a new kamikaze

drone with a range of 124 miles and a cruising speed of 90 miles per hour.

Furthermore, China is

modernizing its strategic missile arsenal. The country is on pace to have more

than 1,000 operational nuclear warheads by 2030—up from 200 in 2019. The two

main companies that produce China’s missiles, China Aerospace Science and Technology

Corporation and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation, have expanded

their facilities and hired additional workers in the last several years. With

this increased capacity, China is building its arsenal of ballistic, cruise,

and hypersonic missiles. In 2021 alone, China launched more ballistic missiles

for testing and training than all other countries combined. In 2020, China

also fielded its first missile with a hypersonic glide vehicle, the DF-17,

which is capable of striking U.S. and other foreign bases and fleets in the

western Pacific. The United States, meanwhile, has struggled with hypersonic

missiles; none of the prototypes it planned to field in 2024 have arrived.

In addition to these

rapidly growing air and sea capabilities, China has made significant progress

in space. In 2023, China conducted 67 space launches—the most in a single year

in the country’s history. China’s launch rockets, global navigation satellite

system capabilities, satellite communications, missile warning systems, and

intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance continue to improve. Its

technologies for countering an adversary’s space capabilities, including

jamming and directed energy systems and antisatellite weapons, are also

advancing. China recently launched a new satellite, Yaogan-41, that can

identify and track car-sized objects on the earth’s surface, thus putting at

risk U.S. and allied naval, land, and air assets throughout the Indo-Pacific

region.

Finally, the PLA Army

is the world’s largest ground force. It operates more battle tanks and

artillery pieces than the U.S. Army. Chinese defense companies have increased

production in nearly every category: main and light battle tanks, armored

personnel carriers, assault vehicles, air defense systems, and artillery

systems.

Peacetime Footing

China’s defense

buildup poses a serious threat to the United States and allies and partners,

including Australia, Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan. China

possesses thousands of missiles, some of which can strike the U.S. homeland.

Others can hit U.S. overseas bases, which host U.S. aircraft, runways, ships,

fuel depots, munitions storage sites, ports, command-and-control facilities,

and other infrastructure. China’s suite of antiship ballistic missiles

threatens U.S. surface ships operating in the South China and East China Seas

and beyond. Looking at this array of Chinese military capabilities, U.S.

Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall III bluntly noted, “China is preparing

for a war and specifically for a war with the United States.”

With such a clear

assessment of the threat, it is perplexing that the United States has not

mobilized its own defense industrial base to keep pace. The U.S. military does

not have sufficient munitions and other equipment for a protracted war against

China in the Taiwan Strait, South China Sea, or East China Sea—all areas where

territorial disputes involving China and U.S. partners and allies, such as

Japan, the Philippines, and Taiwan, could turn violent. In war games simulating

a conflict in the Taiwan Strait, for instance, the United States usually

depletes its inventory of long-range antiship missiles within the first week.

These weapons would be critical in an actual war, as they can strike Chinese

naval forces from outside the range of Chinese air defenses. Especially in the

early stages of a conflict, Chinese defenses would likely prevent most aircraft

from moving close enough to drop short-range munitions.

However the U.S.

defense industrial base lacks the flexibility and surge capability to make up

this and other shortfalls. The United States has an anachronistic contracting

and acquisitions system that is much better suited for the leisurely pace of

peacetime than for the urgency of wartime. As a 2009 U.S. Department of Defense

study bluntly put it, “major defense programs continue to take ten years or

more to deliver less capability than planned, often at two to three times the

planned cost.” The fragility of defense industry supply chains poses another

problem. U.S. defense companies produce limited amounts of key components, such

as solid rocket motors, processor assemblies, castings, forgings, ball

bearings, microelectronics, and seekers for munitions. Some types of equipment,

such as engines and generators, require long lead times. Complicating matters,

China dominates the world’s advanced battery supply chains and has a monopoly

on the global market for several types of raw materials used in the defense

sector, such as some iron and ferroalloy metals, nonferrous metals, and

industrial minerals. If tensions were to escalate or war break out, China could

cut off U.S. access to these materials and undermine U.S. production of

night-vision goggles, tanks, and other defense equipment.

A final challenge is

the workforce. The U.S. labor market is unable to provide enough workers with

the right skills to meet the demands of defense production. The problem is

particularly acute in shipyards, which suffer from a shortage of engineers,

electricians, pipefitters, shipfitters, and metalworkers. In 2024, the U.S.

Navy announced that its first Constellation-class guided-missile frigate would

arrive at least a year late because the shipbuilding company, Fincantieri, was short several hundred workers, including

welders, at its Marinette Marine shipyard in Wisconsin. Frigates play a key

role in carrier strike groups as escort vessels that protect sea lines of

communication. Construction of the Block V version of the Virginia-class

fast-attack submarine, which would be critical for attacking Chinese amphibious

ships in the event of war, is at least two years behind schedule for similar

reasons. Some new guided-missile destroyers, which provide antiaircraft

capabilities, are up to three years behind schedule.

A New Arsenal Of Democracy

China’s defense

industrial base is not without problems. It relies on massive state-owned

enterprises with convoluted and sprawling organizational structures that

undermine efficiency, competition, and innovation. It is also plagued by

substantial corruption; late last year, Beijing removed three highly placed

defense industry officials in a purge apparently related to corruption in the

bid evaluation process. China struggles with some supply chain vulnerabilities,

too, particularly with regard to engines, high-end chips, integrated circuits,

and manufacturing equipment. The reporting sinking of a Chinese nuclear-powered

submarine at the Wuchang shipyard earlier this year suggests that China still

has a way to go in producing some complex systems. And even though the Chinese

military is large and well equipped, it has had no major combat experience

since the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War. But these challenges have not prevented the

Chinese defense industrial base from outpacing its U.S. counterpart in some key

areas.

The United States now

needs to close the gap. The first step is to recognize the urgency of the

problem and the scale of the solution needed. A presidential-led initiative to

revitalize the defense industrial base could achieve this, taking inspiration from

historical models such as Roosevelt’s War Production Board, Harry Truman’s

Office of Defense Mobilization, and Ronald Reagan’s Emergency Mobilization

Preparedness Board. Rather than burdening the Department of Defense alone with

the task of procurement and production, the new body should provide high-level

direction, set priorities, and oversee the policies, plans, and procedures of

the federal departments involved in defense production. Such a structure would

also help integrate the National Security Council, Office of Management and

Budget, Departments of State and Commerce, Congress, the private sector, and

other organizations that play important roles in the defense industrial base.

Washington must also

address the glaring weaknesses in its current defense industrial system. The

Defense Department—including the military services—needs a faster, more

flexible, and less risk-averse contracting and acquisition process. For

starters, it should shorten the timelines for rewarding contracts and help

innovative companies move quickly from prototypes to contracts. Congress also

needs to fund multiyear procurement for key munitions. To address labor

shortages, the Pentagon should offer financial incentives to defense companies

to upskill and reskill workers. The Department of Defense and Congress should

also invest more in high schools, vocational schools, universities, and other

institutions that train and educate individuals for defense industrial base

jobs. And the United States must revitalize its shipbuilding sector. Bringing

back long-dormant subsidies can boost investment in the country’s commercial

shipyards, modernize and expand the industry, and develop a more capable and

competitive workforce in this field.

A year before the

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II,

Roosevelt exhorted the country to “build now with all possible speed every

machine, every arsenal, every factory that we need to manufacture our defense

material.” China’s rapid rearmament and the ongoing wars in Ukraine and the

Middle East are signs that the clouds are darkening. To be ready for a wartime

environment, the United States must once again follow Roosevelt’s advice.

For updates click hompage here