By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Since late 2023, the

Houthis in Yemen have posed an extraordinary challenge to global shipping. As a

result of the Iranian-backed group’s relentless attacks on commercial vessels

in the Red Sea, intended to pressure the United States and its allies over

Israel’s war in Gaza, several of the largest international shipping companies

have been forced to reroute their vessels around Africa to avoid the sea

entirely. According to one estimate, the freight costs of shipping from Asia to

Europe rose by nearly 300 percent from October to March. In an effort to

contain the crisis and defend this vital trade corridor, the United States and

the United Kingdom have conducted hundreds of airstrikes against Houthi sites

in Yemen.

Yet China, whose vast

global trade accounts for a sizable portion of Red Sea traffic, has largely

stood by. Beijing sends $280 billion worth of goods per year through the Red

Sea’s Bab el Mandeb Strait, accounting for nearly 20

percent of China’s total maritime trade. And as a result of the Houthi attacks,

it faces rapidly mounting shipping costs and supply chain disruptions at a

moment when the Chinese economy is already under pressure. Nonetheless, Beijing

has done little in response. In public, Chinese officials have limited

themselves to affirming the importance of safe and open seas; in private, they

have tried to negotiate with the Houthis and their Iranian supporters to secure

the safe passage of vessels linked to China—although multiple such ships have

been attacked.

China’s restraint in

the Red Sea raises important questions about its larger strategy in the Middle

East. Before the current war in the Gaza Strip, Beijing appeared to be

asserting a growing role in the region, including by brokering diplomatic

normalization between Iran and Saudi Arabia and expanding trade ties with Gulf

countries. By claiming to stand up for the Palestinians, the Houthis aim to

increase their standing in the Arab world. and some observers suggest that

Beijing’s reluctance to confront the group is driven by a similarly cynical

effort to enhance its regional clout. While the United States and its allies

bear the burden and potential reputational costs of military intervention,

China can posture as the champion of the global South. Other observers have

gone further, suggesting that China tacitly approves of the Houthi attacks and

is deliberately enabling them through its continued trade with Iran, the

Houthis’ main backer, as part of a broader plan to foment chaos in the U.S.-led

international order.

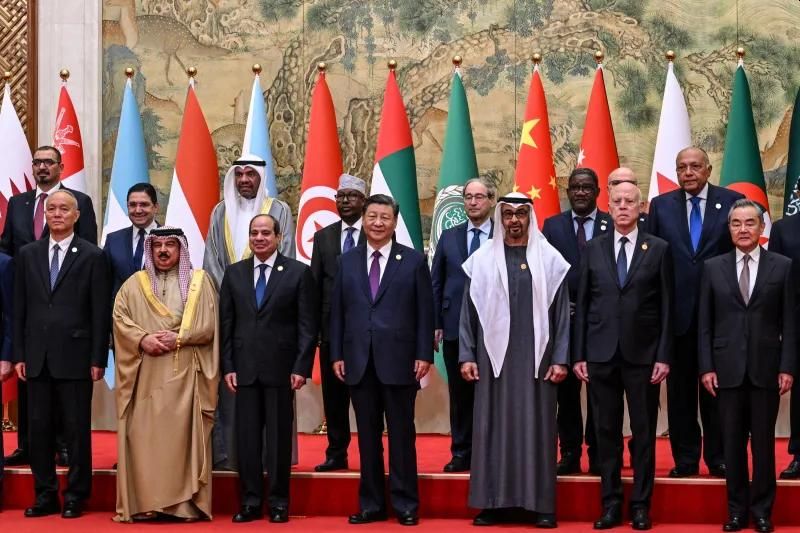

Chinese President Xi

Jinping with leaders of Bahrain, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Tunisia,

in Beijing, May 2024

In fact, both of

these interpretations miss Beijing’s deeper priorities in the region. Although

China’s leaders are glad to avoid military entanglement—and to score easy

diplomatic points with regional governments in doing so—they have no desire to

see the Red Sea attacks continue. They know that their country has too many

economic and military interests at stake. Rather than grow larger, they want

the crisis to end—but without having to spend their own diplomatic, economic,

or military resources to achieve that outcome. To expand its influence in the

Middle East, China ultimately depends on stability, not chaos—a goal that holds

important strategic implications for the United States as it tries to contain

the war in Gaza.

Risky Business

At a time when

China’s economic position looks increasingly uncertain, instability in the

Middle East poses an outsize threat to its economic stability. Given the

region’s importance to China’s international trade, Beijing has signaled that

it wants to secure its supply chains to states in the region. In an interview

with Al Jazeera in April, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi called the Red Sea

“a vital international shipping corridor for goods and energy” and stated that

“safeguarding its peace and stability helps keep global supply chains

unobstructed and ensures the international trade order.”

Indeed, the Houthi

attacks on commercial vessels threaten China’s supply chains in the region. The

campaign has forced many international shipping companies to redirect their

vessels to the far longer route around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, adding

days to normal shipping times and raising fuel costs by some 40 percent.

Moreover, roughly 70 percent of China’s exports to the United States normally

pass through the Red Sea, and this trade now incurs significantly higher

shipping costs in addition to the long delays. For Beijing, the timing could

not be worse. Facing sluggish domestic consumption and an imploding property

sector, the Chinese government is seeking to boost growth through high-value

exports such as cars, electric vehicle batteries, and solar panels. Shipping

makes up a relatively high percentage of these products’ overall cost

structure, leaving them particularly vulnerable to price shocks.

Disruptions to global

trade could potentially jeopardize China’s energy and food security as well.

For the moment, the country’s imports in these two strategic sectors are

sufficiently diversified to make a major crisis unlikely, even if the Houthis

manage to bring Red Sea shipping to a complete standstill. Bumper grain

harvests in recent years and the increasing use of electric vehicles and

domestically produced clean energy give China additional layers of protection

against an energy crunch induced by supply chains. Nonetheless, foodstuffs and

hydrocarbons are traded on global markets and therefore highly sensitive to

turmoil wherever it occurs. Alongside the Red Sea crisis, Russia’s war in

Ukraine has caused major disruptions to grain shipments through the Black Sea,

and droughts and low water levels have limited all forms of trade through the

Panama Canal. The longer the Houthi attacks continue, the more these pressure

points will drive up food and energy prices worldwide, including in China.

Beijing knows that a

prolonged crisis could jeopardize its growing economic interests around the Red

Sea. China holds significant stakes in port operations near the Suez Canal— 20

percent at Port Said at the northern end and 25 percent at Ain Sokhna in the

south—and has plans to invest in new port terminals on both coasts of the sea.

Reduced shipping means reduced revenue for Chinese state-owned enterprises

involved in port operations and for private Chinese firms moving cargo between

China and Europe. Harm to Egypt’s economy, for which Suez Canal traffic has

become a lifeline in recent years, is also bad news for China. Now Egypt’s

fourth-largest creditor, Beijing has billions at stake in the country.

What is more, China

has positioned itself as a key player in the Middle East’s clean energy

transition, giving it a vested interest in the region’s own economic stability

and supply chains. In June 2023, the Chinese electric vehicle producer Human

Horizons signed a $5.6 billion deal with Saudi Arabia. And this spring, the

United Arab Emirates and China signed a new memorandum of understanding under

Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative to deepen their economic engagement,

particularly on green technology.

The Red Sea crisis

has also exposed Beijing’s ambivalence about its military presence in the

region. Since 2008, China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy has stationed a fleet

of in the sea, including a destroyer and frigate, to conduct anti-piracy

missions and buttress its status as a rising regional power. It also maintains

its only overseas naval base in Djibouti, on the nearby Gulf of Aden. In

theory, China could use its forces in the region to strike back at the Houthis

or to escort commercial vessels into and out of the Red Sea. Yet China’s

reluctance to protect its own commercial ships underscores its general aversion

to military intervention—even in a case where it has a base close to the

conflict and its own economic interests are at stake. The longer the attacks

continue, the greater the risk that Beijing finds itself in a situation in

which it is compelled to deploy its naval forces and become directly involved

in the conflict. Paradoxically, given the priority it places on avoiding

military entanglement, China’s naval assets in the region could prove a

liability, if the Houthi campaign becomes prolonged.

Less Chaos, More Control

Despite Beijing’s

economic and military assets in the region, some in Washington have suggested

that China’s leaders are profiting from the Red Sea predicament. the former

U.S. deputy national security adviser Matt Pottinger and former U.S.

congressman Mike Gallagher argued that Beijing’s inaction with respect to the

Houthi attacks was part of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s “policy of fomenting

global chaos.” According to this theory, China supposedly benefits from and

seeks to fuel global crises that entangle the United States and thereby expose

Washington’s weakness in managing the Western-led international order.

Yet this logic

distorts China’s calculations. Indisputably, Beijing sees itself as a rising

power, and Chinese leaders have made clear that they are dissatisfied with U.S.

leadership of global affairs. And in the short term, China may derive some

benefit from staying on the sidelines of controversial U.S. military

interventions. But that does not mean it wants to encourage conflict around the

world. This is especially true in the Middle East. Should the Red Sea crisis or

the war in Gaza spiral into a wider war, this could further upend Chinese trade

and investments across the region.

A Houthi rally celebrating the seizure of a cargo ship

in the Red Sea, Sanaa, Yemen, February 2024

The theory that

Beijing is deliberately sowing chaos misreads its understanding of its own

rise. In recent years, China’s flagship research institutions and think tanks

have published theories on the “general laws” governing the rise and fall of

great powers. According to these models, the world has passed through a series

of great power “cycles” over the last half-millennium or so, including those of

the Spanish and Portuguese in the sixteenth century, the Dutch in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the British in the nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries. Each of these, in the Chinese view, lasted for

roughly 100 years and ended in disorder and upheaval, and the hegemony of the

United States established after World War II is continuing this trend. In a

2021 essay, Wang Honggang, a scholar at the China

Institutes of Contemporary International Relations in Beijing, characterized

the terminal stage of this cycle as “world crisis,” a decades-long period of

destruction and fierce competition between states.

Xi has made clear

that he subscribes to this theory. Since 2018, he has spoken constantly of

“changes unseen in a century,” an apparent allusion to upheaval and innovation

related to the erosion of American power, from the 2008 global financial crisis

and ongoing populist backlash against liberal democracy to the rapid recent

advances in biotechnology and artificial intelligence. China’s top officials

and academics hope and may sincerely believe that these changes will enable

their country to gain dominance in the post-American cycle. But they are also

keenly aware of the challenges that Beijing must address to survive the tumult.

Xi has mobilized the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda apparatus to promote

“calamity consciousness” —a calm yet vigilant readiness to seize on

opportunities arising from disaster—and ensure that party officials are

prepared for the “major risks and challenges” lying ahead.

As a result, Beijing has

sought to minimize its exposure to global instability and maximize its ability

to survive and adapt. At the level of grand strategy, this means diversifying

supply chains and trade routes to provide ways around local or regional

conflicts or to limit the impact of potential economic sanctions. As the

geopolitical analyst Parag Khanna argued recently, Houthi attacks on Red Sea

shipping are a textbook example of precisely the sort of risk that Beijing’s

Belt and Road Initiative aims to mitigate: by building more and more diverse

supply chains, China can better insulate itself from any given supply shock,

whether caused by geopolitical events or climate change. The country is also

promoting overland trade routes, such as a rail corridor through Central Asia

to Europe, that can serve as backstops to disruptions along major shipping

routes. In a similar vein, Beijing has labored over the past decade to offset

its reliance on American corn, wheat, and beef by expanding its commodities

trade with Argentina, Brazil, and other Latin American countries, as well as

Asia.

These strategies are

readily apparent in Beijing’s Middle East diplomacy. In 2021, China entered

into a valuable energy and economic partnership with Iran. another vocal critic

of the Western-dominated system. It also established and upgraded “strategic partnerships”

with U.S. partners in the region, including the UAE in 2012 and Saudi Arabia in

2022, and continues to bolster its influence over Arab states through the

China-Arab States Cooperation Forum. Beyond extending its diplomatic sway— as

shown by its mediation of the Iranian-Saudi rapprochement in March 2023—Beijing

sees these agreements as a means to secure reliable access to energy and build

infrastructure.

Strategic Shirking

For the moment, the

Houthis are showing no signs of relaxing their stranglehold on the Red Sea.

Testifying before a Senate committee in early May, the U.S. director of

national intelligence, Avril Haines, predicted that the threat of attack was

“going to remain active for some time.” The international shipping company

Maersk expects the shipping disruptions to continue through 2024 and has

reported that “the risk zone has expanded, and attacks are reaching further

offshore.” Indeed, in a round of attacks the first week of June, Houthi rockets

and drones struck several commercial ships, and the group also launched an

attack on a U.S. aircraft carrier, though U.S. officials maintain that it was

unsuccessful.

Although such strikes

also threaten Chinese interests in the region, Beijing’s options are limited.

It knows that any military response it might undertake would be no more

successful than those of the United States and the United Kingdom. It also

needs to maintain the support of Middle East leaders in its bid to fill gaps

left by the West across the region. As a result, China is likely to respond

with more of the same, doing what it can to safeguard its own interests, avoid

further entanglements, and withstand future disturbances.

In line with their

view that American power is declining, Chinese leaders will continue to score

easy diplomatic points in the Middle East where they can. Thus, in April, they

invited members of the rival Palestinian organizations Hamas and Fatah to Beijing

to foster reconciliation and to outline a possible unity government for postwar

Gaza and the West Bank—however remote such a plan may be at present. As polling conducted by Michael Robbins, Amaney Jamal, and

Mark Tessler in late 2023 and early 2024 indicates, Arab citizens’ opinion of

China has improved since October 7, although few respondents agreed that China

was seriously committed to safeguarding the rights of Palestinians.

Ultimately, China

seeks in the Middle East what it is seeking elsewhere: to expand its trade

ties, diversify its sources of energy and food imports, and assert its growing

influence as a great power, all while avoiding military entanglements. Chinese

leaders recognize that rhetorical opposition to Western dominance in the region

is a low-cost way of soliciting broader support, especially in the global

South. Their greatest priority is not to sow more instability but to guard

China’s interests and adapt to a threatening geopolitical environment. To

accomplish that, they may employ cynical and opportunistic methods, but these

are based on managing, not creating, crises.

For the United

States, this means that China will remain a diplomatic competitor in the Middle

East. Washington should expect Beijing to continue to decry American hegemony

and cast itself as a more benign and constructive great power. But contentious

rhetoric should not deter U.S. policymakers from recognizing that China’s real

interests lie in staying out of conflict and extracting what gains it can,

leaving the responsibility of restoring regional stability to other countries.

China won’t be willing to lay much on the line for peace, but it won’t stymie

the process, either.

For updates click hompage here