By Eric Vandebroeck

Two years ago, all hell broke loose on the heads of

the Rohingya as Myanmar military launched so-called 'clearance

operations' which were really a search and destroy mission against any

Rohingya person in northern Rakhine state. In 2018 already a United

Nations-backed Fact-Finding Mission found

sufficient information to warrant the investigation and prosecution of

senior military officials for grave crimes, including genocide, in Rakhine

State.

Then on 8 August 2019

in a staggering verdict, the U.N. Independent International Fact-Finding

Mission on Myanmar in a new report (A/HRC/42/50)

stated that there will be no long-term peace in Myanmar and no return of

Rohingya refugees unless there is accountability for the “brutality” of the

Asian country’s military forces.

And while the latter

report was first announced on 4 July 2019 during a meeting in London it should

not come as a surprise the sudden willingness of the government of Myanmar to

start bringing 3,000 Rohingya

refugees who are facing increased hardships back, so they as is claimed,

can live on their ancestral land in Myanmar whereby Min Thein, director of

Myanmar’s social welfare ministry, added

that security measurements are now in place for returning refugees.

That is until a

revealing BBC report was aired

on 9 Sep. exposing it in what best can be described as a sham. An

experienced BBC correspondent Jonathan Head was able to find evidence that, far

from welcoming the Rohingya back, the authorities In Rakhine state have been

erasing all trace of their villages. And validates why

Rohingyas are scared of returning home as Myanmar by no means has created a

conducive environment.

The BBC saw four

locations where secure facilities have been built on what satellite images show

were once Rohingya settlements all while officials denied building on top of

the villages in Rakhine state this in spite of the

presentation of evidence that proved otherwise.

As Jonathan Head

reports: "The only visible preparations for a large-scale refugee return

are dilapidated transit camps like Hla Poe Kaung, and relocation camps like Kyein Chaung. Few refugees are likely to overcome the

trauma they suffered two years ago for that kind of a future. It raises

questions over the sincerity of Myanmar's public commitment to take them back.

I was able to meet a

young displaced Rohingya on my way back to Yangon. We had to be discreet;

foreigners are not allowed to meet Rohingyas without permission. He has been

trapped with his family in an IDP camp for seven years, after being driven out

of his home in Sittwe, one of 130,000 Rohingyas

displaced in a previous outbreak of violence in 2012.

He is unable to

attend university, or to travel outside the camp without permission. His advice

for the refugees in Bangladesh was not to risk coming back, and finding

themselves similarly confined to guarded camps." Thus the so-called

repatriation plan is nothing but a scheme designed to whitewash the Myanmar

military’s crimes and to help it escape accountability."

In a report published

on 16 Sept. the UN fact-finding mission said that 600,000

Rohingya in Myanmar continue to live under threat of genocide.

Above Kyein Chaung relocation camp in northern Rakhine State,

where Rohingya refugees could be resettled. But an existing Rohingya village

was demolished for this, one of the dozens erased from the landscape since

2017."

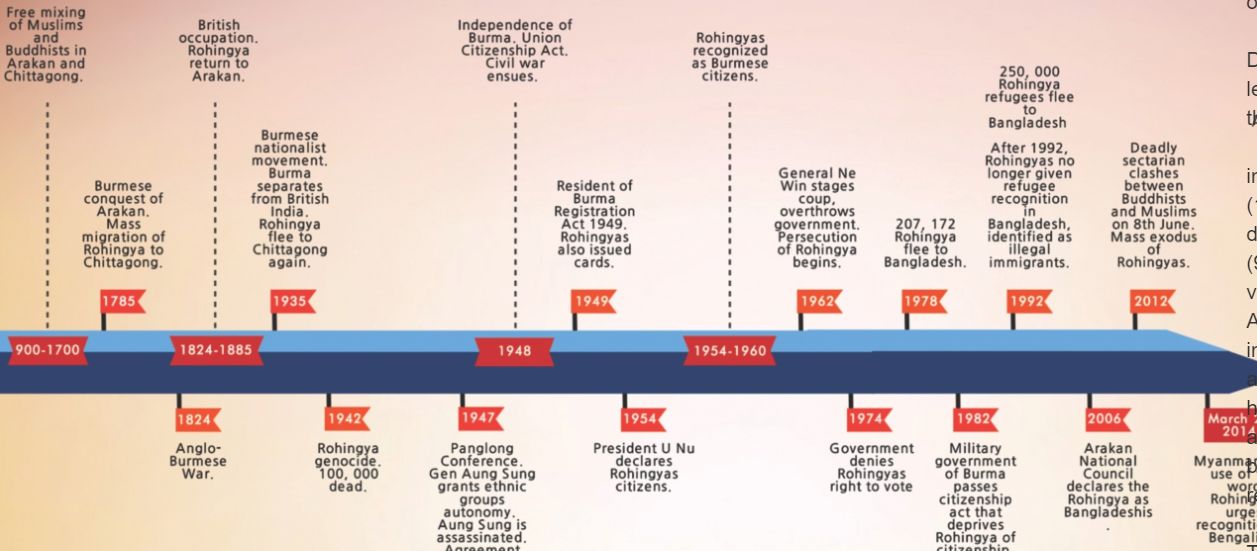

The politics of statelessness

In effect, the battle

for independence was also a battle for ethnic supremacy, and that lies at the

heart of this current crisis. The Rohingya were never accepted.

“They are not really

Burmese. They are Bangladeshis,” said Aung San Suu Kyi to former UK Prime

Minister David Cameron, as featured in his new book today.

This is an example of

how the present-day Myanmar government misrepresents existing real and invented

disputes about the Rohingya.

Rohingya's initially

came to be lumped in with Indian Muslims (specifically Chittagonians)

in Burmese and Rakhine nationalist rhetoric in the 1930s and 1940s and thus the

Muslim population came to be considered the colonizing other. This whereby

Buddhist Rakhines in the colonial legislature in

Rangoon post-1937 already began to differentiate themselves from their Muslim

neighbors, but it was really in the Japanese invasion

when the battle lines were drawn and the Muslims (who supported the

British) and the Buddhists (who supported the Bamars

& Japanese) separated into distinct communities.

Trying to bring the

ongoing discussion to a conclusion in August 2017, a commission chaired by Kofi

Annan issued a comprehensive set of recommendations, including lifting all

restrictions on the Rohingya, and offering them a path to citizenship, that, if

implemented, could go a long way toward improving the Rohingya’s safety and

legal standing in Myanmar.

Reference is here to

Myanmar's 1982 Citizenship Law that says only people of 135 ethnic groups

identified by the state are citizens of the country. These are the groups which

settled in Myanmar before 1824 when the British first occupied the country. Despite

generations of residence in Myanmar, the Rohingya are not considered to be

amongst these official indigenous races and are thus effectively excluded from

full citizenship.

Setting aside the

absurdity of counting ethnic groups for a moment, the figure of 135 ethnic

groups in Myanmar as suggested by experienced Myanmar researcher Bertil Lintner

is propaganda, crafty by the Tatmadaw to divide various ethnic groupings into

smaller constituent units. Late British censuses counted around 20 groups.

The first official

list of all 135 national races was produced just prior to the 2014 national

census. The list mentions a dozen different “national races” in Kachin state,

nine in Kayah state, 11 in Kayin state, 53 in Chin state, nine separate ethnic

Bamar groups, one in Mon state, seven in Rakhine state and 33 in Shan state.

Some like Lintner

suspect the military divined the supposed number of national races through

numerology. When the SLORC junta declared there were exactly 135 national

races, some analysts noted that the three digits – 1, 3 and 5 –summed equal the

number 9, the military’s supposedly lucky number symbolizing unity.

Under previous

military regimes, major decisions were almost always taken on dates whose

digits added up to the number 9. The 1988 military takeover occurred on

September 18 of that year. Then pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi was put

under house arrest on July 18, 1989, while the later annulled 1990 election her

party won was held on May 27. At one point, Myanmar even had 45 and 90 kyat

banknotes.

Using numerology as a

guide to national peace and unity in a nation with as many diverse ethnic

groups as Myanmar, and where civil war has been raging since independence in

1948, hardly seems like a sensible way forward. A more realistic, fact-based

approach, one which examines why all previous attempts to establish peace and

reconciliation have failed, is clearly needed.

Whether the country

should be a federal union, as most ethnic minority groups demand, or maintain a

highly centralized national structure, as the military believes necessary to

prevent disintegration on ethnic lines, the issue will not be settled any time

soon if there are as many as 135 seats representing each supposed national race

at the peace talks table.

As for the rationale

for rendering the Rohingya stateless boils down to a consensus that the

Rohingya are uninvited guests who have overstayed their welcome.

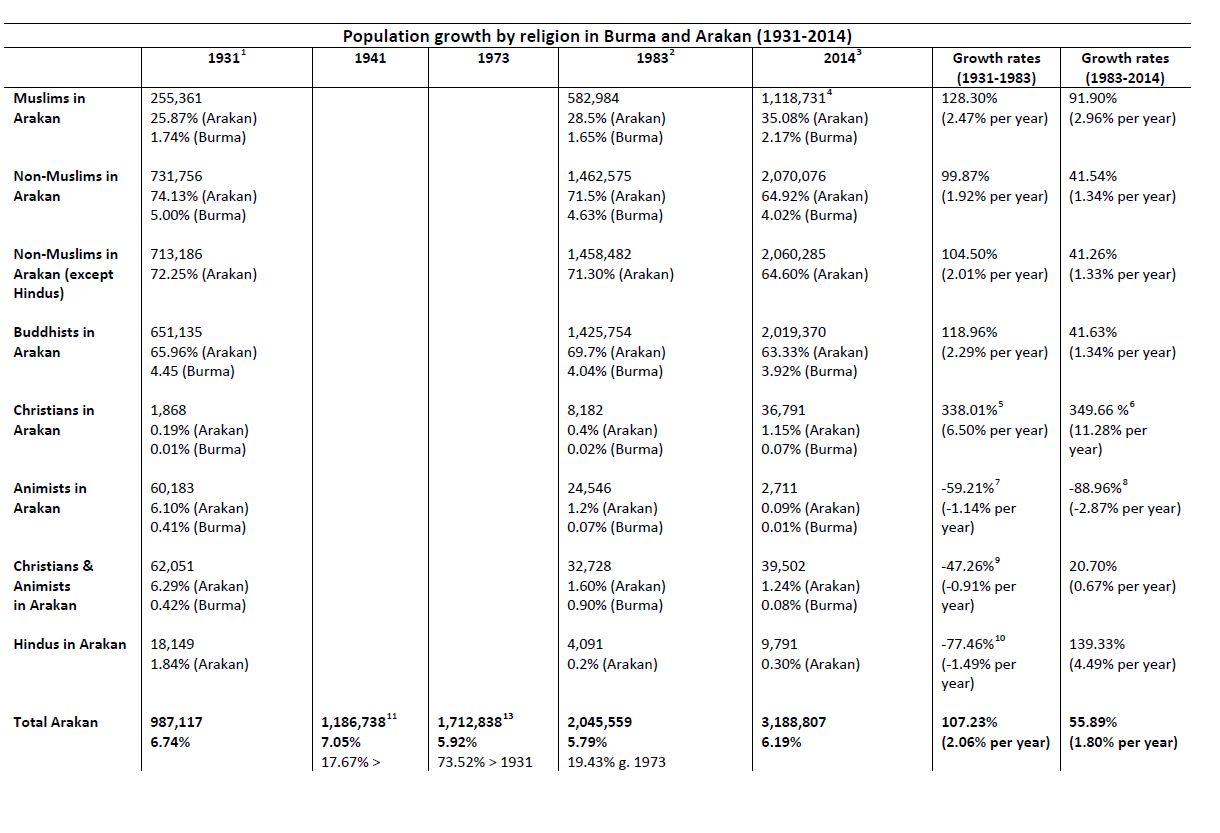

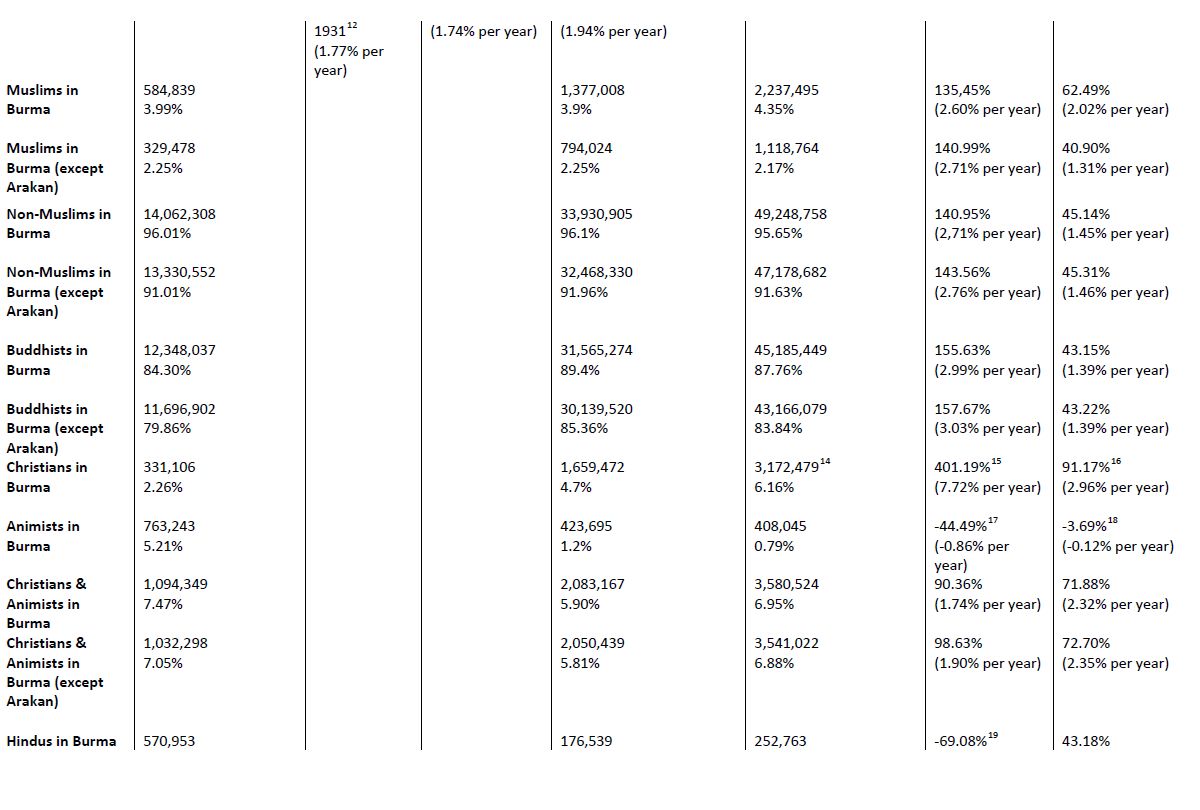

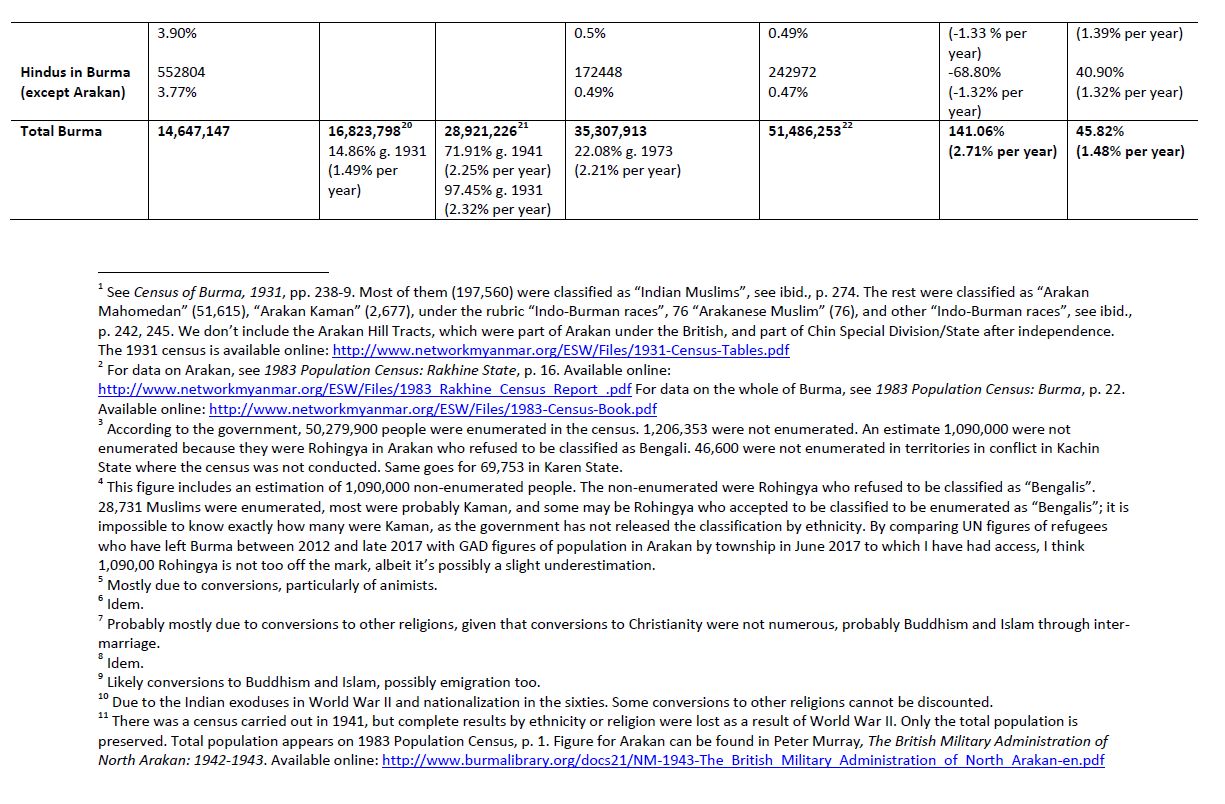

Countering the

narrative of the leaders of Myanmar recent historical studies have shown that

Arakan, rather them being only recent illegal immigrants, was first settled and

established by "Bengalis," as inscriptions pre-dating the Mranma expansion into the Arakan littoral make clear. Not

to mention that (as suggested

by scholar Kyaw Min Htin) the referent "Rakhine" has been shown

to have been floating and evolving in terms of its meanings. In other words what is now considered the Rohingya ethnicity

emerged in Arakan, to begin with.

Arguing that

arbitrarily choosing 1823 as the cut-off date resonates with a political

purpose and the chosen date appeals to Burmese ethnonationalism because it

negates what occurred under subsequent British colonial rule. Whereby it is an

irony that Myanmar claimed territorial sovereignty over Arakan without actually

giving citizenship to a section of people.

The opportunity military planners in Myanmar were

waiting for

According

to the UN investigation giving military planners in Myanmar the opportunity

they were waiting for on 25 August 2017 a rag-tag group of the Arakan Rohingya

Salvation Army, or ARSA, appeared out of the darkness armed mainly with sticks

and machetes and stormed some thirty police posts, killing about a dozen

Myanmar security personnel in Rakhine State (also known as Arakan State) in

western Myanmar. Apparently (according to the UN investigation), the Myanmar

military responded with overwhelming force and brutality, reportedly killing

and raping civilians indiscriminately and burning villages. Within a few weeks,

under the pretext of “clearance operations” against a population it accuses of

having immigrated illegally from Bangladesh and harboring extremists and

terrorists, the military forced more than half a million Rohingya to flee

across the border into Bangladesh, where they joined another half-million or so

who have fled the apartheid-like conditions and periodic pogroms of recent

years.

Yet despite the

allegations of the military and some Buddhists in the country that this group

is linked to IS there are no links between insurgent groups and Islamic

jihadist groups, and to in addition label ARSA as “Bengali terrorists” to

justify excessive force is distorted and manipulative. ARSA does

not have broader goals related to Islamic fundamentalism, and their stated

purpose is to aid the Rohingya and secure their rights as citizens of Myanmar.

The response of the Tatmadaw has also been disproportionate, killing hundreds

through “area

clearance operations” and displacing over eighty-eight thousand people.

Lastly, the recent Fact-Finding report released by the Office of the United

Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) noted that the Myanmar

government has published

photos and names of 1,300 supposed ARSA terrorists without due process and

that throughout their interviews, no Rohingya mentioned ARSA as a factor in

feeing Rakhine state. Overall, ARSA is a low-level insurgency group inflicting

minimal casualties on Myanmar forces. Although posing a threat to government

forces, the Tatmadaw has responded in kind with premeditated and ruthless

retaliation against the civilian Rohingya population. This negates the Myanmar

government narrative that the violence in Myanmar is the result of a Rohingya

insurgency. The term “ethnic cleansing” is a broad term to denote cases where

an ethnic, national, or cultural group is being threatened with erasure by

another group. This term has been applied to the Rohingya on numerous

occasions. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has referred

to the situation in Rakhine state as ethnic cleansing including

that of genocidal intend.

Press freedom besieged

In December 2017 two

Reuters reporters were jailed for doing their job. Their “crime” was

investigating the military's crimes in Rakhine and finding credible evidence of

mass executions of Rohingya by state security forces In January 2019 the appeal

of these reporters, sentenced in 2018 to seven years in jail, was rejected, a

decision with far-reaching consequences for Myanmar’s reputation and freedom

of expression The ruling is thither evidence of the state's determination to

bury the truth about the 2017 atrocities in Rakhine. In May 2019 the reporters

were pardoned and released from prison, but then conviction stands and there

was no apology for the gross miscarriage of justice or for the year and a half

of separation from their families. Whereby striking was also that most

opposed to freeing two reporters was Aung San Suu Kyi. The NLD and "the

Lady" seem to have forgotten how freedom of expression was once a

core value. Critics assert that she has become increasingly authoritarian,

isolated, and intolerant of criticism.

Ronan Lee published a

study showing that the state media publication, the Global New Light of Myanmar

newspaper, has actively produced anti-Rohingya speech in its editions and

influenced violent narratives about the Rohingya Muslims circulating on social

media. It shows how official media contributed to a political environment where

anti-Rohingya speech was made acceptable and where rights abuses against the

group were excused. While regulators often consider the role of social media

platforms like Facebook as conduits for the spread of extreme speech, this case

study shows that extreme speech by state actors using state media ought to be

similarly considered a major concern for scholarship and policy.

The military believes

that as long as it can concoct a scenario of plausible deniability, invoke

terrorism, play up IS links, and conceal the evidence of crimes against

humanity, it can avoid accountability. What makes the Rohingya crisis unique in

comparison to the long list of historic ethnic insurgencies is the way in which

the Central Burmese called Bamar have organically rallied around the government

and military. From anti-government rallies, the last year has for the first

time seen mass pro-government rallies. Thus large numbers of Bamar across many

classes have been involved in online harassment campaigns of anyone who opposes

the brutal treatment of the Rohingya.

Some 65 percent of

the population is ethnic Bamar, but there are more than 100 other ethnicities, dozens

of which have taken up arms over the years." The large number of

non-Bamar parties comprising members of single ethnic groups is a testimony to

the fact that the non-Bamar nationalities prefer to go their own way.

Suu Kyi's current

Bamar led government’s and military’s premise seems to be that “a rising Bamar

tide will lift all ethnic boats”, but in reality, that

isn’t the case. In 2017 a guide at the Shwedagon

Temple in Yangon vigorously

defended Ma Ba Tha (Association for the

Protection of Race and Religion, a Buddhist nationalist group) and the military

campaign against the “Bengali," asserting that the term “Rohingya" is

invented to gain international sympathy.

The Rohingya as invented to gain international

sympathy narrative

As I pointed out before the above Ma Ba Tha narrative is also applied by some scholars, like when a

Harvard university student wrote in the Diplomat “[I]n even a cursory survey of

Rohingya history, it is clear that the Rohingya are not an ethnic, but rather a

political construction…. At stake are issues of legitimacy. The international

community’s use of the term ‘Rohingya’ validates the narrative of essentialising a Muslim identity in Rakhine state”.

They argue that

despite a general understanding that a part of the Arakan Muslims had deep

roots in the country and that Rakhine history cannot be understood without its

social and religious complications with Bengal from the past down to the

present, a pervasive Rakhine narrative about Muslims in Arakan has viewed them

as ‘guests’ who have betrayed the trust of their hosts by claiming territorial

ownership. The claim of a distinctive ethnicity made by Rohingyas is,

therefore, considered by them as fake.

Many such analyses

give a false sense of complexity that seeks to water down murderous ethnic

cleansing and deny any political urgency. Also, as I pointed out in a section

titled "The Rakhine/Rohingya ethnicity

conundrum" a good example of that is represented by an otherwise

respected scholar Jacques P. Leider.

Rakhine histories

here are part of a self-consciously political project to appropriate Arakanese

cultural heritage as their exclusive national patrimony, motivated by the

dramatic collapse of Arakanese power at the hands of Bamar and British invaders

and colonizers. Within the Tatmadaw's ideology, which supplanted "The

Burmese Way to Socialism," is considered a "national race" is

vitally important to be considered equal under the law and in the eyes of the

state. The answer isn't to place Rohingya within this, but to end it. The

problem is that the Burmese defend their apartheid state under the guise of

"national sovereignty," and neither the U.N. or any world power has

any interest in compromising that liberal shibboleth for the sake of a couple

of million persecuted Muslims.

A recently published

article offered some striking imagery of the

two-year Rohingya crisis in three timelapse satellite GIFs.

What to expect next?

Myanmar's position on

the Rohingyas’ designation is as hardline as ever. Zaw Htay, a government

spokesman, said that “action”

will be taken against media and officials who had described the refugees as

“nationals” in their reports or comments ahead of the failed repatriation.

The Ministry of

Construction had apparently used the “nationals” term in a statement quoted by

state-owned media, including the TV and radio station MRTV, the Mirror, Myanmar

Alin and the Global New Light of Myanmar. The MRTV report was aired on August 12

and several newspapers ran it the next day, followed by corrections on August

14.

The UNHCR thus must

be aware that nearly all the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are there to stay,

despite

recently giving over 500,000 of them fraud-proof, biometric identification

cards, supposedly as a first step “to safeguard their way home.”

“Most of these people

are stateless and most of these people have not had any form of identification

document, so far the vast majority of the Rohingya refugees, this is the first

ID, a first proof of identity that they have,” UN spokesperson Andrej Mahecic told journalists in Geneva in July. What he failed

to mention was that by admitting that the refugees previously had had no formal

ID cards, they would also be unable to prove any previous residence in Myanmar

and therefore (apart from the token 3,000 Rohingya refugees Myanmar suggested

they are willing to take) not be eligible for repatriation as far as Myanmar

authorities are concerned.

At the same time, resentment

against the Rohingyas is growing in areas south of Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh,

where most of them are encamped. According to local sources, the influx of

refugees, and international refugee workers, has caused a spike in prices of

basic commodities. Many locals also fear they will lose their jobs as refugees

increasingly sneak out of the camps seeking work for lower-than-local wages.

Forest areas near the densely populated camps have been denuded for building

materials to construct homes and shelters for the refugees. All this while more

Rohingyas made attempts at entering Bangladesh by crossing the River Naff.

Bangladesh’s newfound

hardline approach to Rohingya is unhelpful and misguided, as it assumes

responsibility for the Rohingya’s residence in Bangladesh lies with the

Rohingya themselves instead of Myanmar’s authorities.

However, how much it

would cost Bangladesh as host of the camps if none of the refugees are returned

to Myanmar was not mentioned in the UNDP/PRI report, and that now appears to be

the most likely, and from Dhaka’s perspective, worst case scenario.

Agencies like the

World Food Program have launched

a relief operation to aid thousands of Rohingya refugees whose possessions have

been swept away in the torrential rains that hit Cox’s Bazaar in Bangladesh

this week.

And the UN seems

clear what it wants to do, Radhika Coomaraswamy, a Sri Lankan lawyer who is one

of the U.N. Independent International Fact-Finding Mission three international

experts, cited a number of options: having the Security Council refer the matter

to the International Criminal Court, establishing an ad-hoc tribunal on Myanmar

or having countries with universal jurisdiction use it to deal with the plight

of the Rohingya Muslims who fled military crackdowns to Bangladesh. In

parallel, she said, through the Genocide Convention a demand can be made to

the International Court of Justice for compensation and reparations to the

Rohingya.

During a 17 Sept.

news conference in the Palais des Nations a UN panel stated that Myanmar incurs

state responsibility under the prohibition against genocide and crimes against

humanity, as well as for other violations of international human rights law and

international humanitarian law. And that Myanmar’s civilian leader, Daw Aung

San Suu Kyi, could

face prosecution for crimes against humanity committed by the military.

The finding of “state

responsibility” means that Myanmar should be brought before the International

Court of Justice (ICJ) for failing to honor its obligations under the 1948

Genocide Convention, one of few international human rights instruments it has ratified.

“The scandal of

international inaction has to end,” said Mission Expert Christopher Sidoti.

For updates click homepage here