By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Sanctions

Puzzle

It’s been more than 16 weeks since U.S. sanctions meant to “impose severe

costs” on Russia’s economy. Those hoping that an economic collapse might change

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s mind on his invasion of Ukraine are still

waiting.

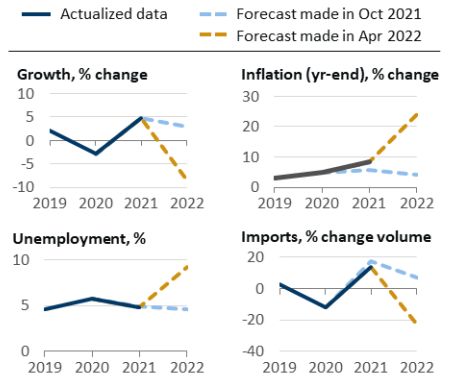

Sanctions that isolate Russia are a shock to the global economy, which

was still struggling to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. The sanctions have

likely contributed to disruptions in global supply chains, higher global

commodity prices, and a slowdown in global economic growth.

Specific EU sanctions can be seen

in detail here.

Yet even as it shuts down some of its economic

reporting, the Russian government announced a budget surplus for the first five

months of this year of roughly $26 billion, spurred in part by high

oil prices. First-quarter GDP figures out today are expected to show a 3.5

percent increase from the same time last year—though a decrease of as much as

10 percent of GDP is likely by year’s end.

“The scale of international sanctions would have caused [an] economic

collapse if they’d come out of nowhere,” Chris Weafer

of Macro Advisory in Moscow told the BBC.

But Russia’s been experiencing sanctions on an incremental basis since

2014. There’s been an enormous ratcheting up, but there’s also an element of

this being something the country’s already been dealing with.

Elsewhere, others under U.S. sanctions go about their business: North

Korea is reportedly preparing a new nuclear test, its seventh overall;

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro is finishing a Middle East tour, and Iran

is once again ramping up its uranium enrichment.

At the White House, officials are getting spooked that the economic

measures they unleashed at the beginning of the war are having a boomerang

effect. According to Bloomberg, Biden administration

officials “are now privately expressing concern that rather than dissuading

the Kremlin as intended, the penalties exacerbate inflation, worsening food

insecurity and punishing ordinary Russians more than Putin or his allies.”

That the sanctions don’t have the desired effect shouldn’t be a

surprise, it is quite unrealistic to expect that economic sanctions against a

great power—and that would be Russia today—will substantially deter a policy

course that the leadership has set upon. No experience validates that

expectation.”

When sanctions have worked, they tend to be on smaller, weaker nations.

Sierra Leone, the Dominican Republic, and Nepal are examples of when sanctions

have achieved their desired outcome for the countries imposing them.

So why do they persist as a

tool of diplomacy?

In part, sanctions can be a helpful way of placating a domestic

audience, especially when a government doesn’t want to appear weak.

“When you have a big offense like this invasion, I would say sanctions

are almost inescapable just to answer the potential domestic criticism, and

then the government will tend to exaggerate the impact of the sanctions imposed,”

Hufbauer said.

Perhaps that’s why they continue to be popular among U.S. policymakers.

Cornell University’s Nicholas

Mulder found in his book, The Economic Weapon: The Rise of

Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War: “Sanctions use doubled in the 1990s and

2000s from its level in 1950 to 1985; by the 2010s, it had doubled again.”

Nevertheless, he argued, “while the use of sanctions has surged, their odds of

success have plummeted.”

Even if they don’t lead to the intended outcome, don’t expect Russian

sanctions to come off soon. Just ask Cuba or Iran, as powerful constituencies

within U.S. politics continue to keep pressure on—even if changes aren’t in

sight. “I think these are going to be in place for a long time,” Hufbauer said. “As long as Putin is in place, we

think it’ll be tough to lift the sanctions.”

Ghosts of sanctions past

In the case of North Korea, it might be time to give up altogether and,

as FP columnist Howard French writes, “consider

what has never been tried before: ending the state of hostility between

Washington and Pyongyang that has fueled North Korea’s push for nuclear

armament.”

French proposes ending the North’s economic isolation, understanding that

decades of sanctions have not stopped it from pursuing its nuclear goals. “The

best hope for peace may lie instead in convincing the North that it has little

to fear from the outside world and can thus afford to incrementally relax its

posture and perhaps even normalize its relations with foreign nations,” French

writes.

For updates click hompage here