By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

China and Russia Will Not Be Split

Many American foreign

policymakers dream of being the next Henry Kissinger. Whether they admit it or not,

they look to him as the model of shrewd calculation of national interests,

geopolitical acumen, and devotion to diplomacy. He was a leader who struck

grand bargains with global effects. And no diplomatic maneuver is more

quintessentially Kissinger than the U.S. opening to China in 1972.

As great-power

competition heats up again, today’s U.S. policymakers may be tempted to try to

replicate that success by orchestrating a “reverse Kissinger”—pulling Russia

closer to balance a rising China, in a reversal of what Kissinger did beginning

in 1971, when he was serving as national security adviser to President Richard

Nixon. In an influential paper published in 2021 by the Atlantic Council, the

anonymous author, a former government official, proposed that Washington

“rebalance its relationship with Russia” because “it is in the United States’

enduring interest to prevent further deepening of the Moscow- Beijing entente.”

In its first few months, the Trump administration has seemed to warm to this

idea. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has called for the United States “to have

a relationship” with Russia rather than let it “become completely dependent on”

China. Running a “reverse Kissinger” is also the perfect alibi for President

Donald Trump’s courtship of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Americans dislike

Putin, but if Trump’s embrace of the Russian dictator can be presented as

pragmatic, realpolitik, or otherwise Kissinger-esque,

they might accept it.

In the abstract,

drawing Russia away from China to shift the balance of power in favor of the

United States sounds appealing. In reality, the idea is a bad one. Most

important, the analogy to the Cold War of the 1970s is flawed. Back then,

Washington recognized and exploited, rather than produced, a deep Sino-Soviet

split to improve relations with Beijing. Not only does such a split not exist

today, but Beijing and Moscow are now true strategic partners. Both Putin and

Chinese leader Xi Jinping see the United States as the greatest threat to their

respective countries and have built an institutionalized relationship based on

converging material interests and common autocratic values. Putin has no reason

to give up China’s extensive, concrete, and reliable support to Russia’s

civilian economy and defense industry in exchange for ties to Washington that

may not last past the end of Trump’s term, in 2028.

Moreover, in the

improbable event that the United States could peel Russia away from China, a

new rapprochement with the Kremlin would bring few real benefits to the

American people and come at a steep cost to other U.S. interests. Putin would

never help the United States deter or contain China. Instead, he would leverage

American eagerness for better relations to play Washington and Beijing off each

other as he rebuilds Russia’s economy and military. Even the process of

courting Moscow would be damaging because any favor the United States shows

Russia alienates Europe. Militarily, Russia has far less to offer the United

States than NATO does, and it is an inferior trading and investment partner

compared with the European Union. Trying to win Russia over would mean swapping

a strong, rich, and dependable set of allies for a weak, poor, and fickle

partner. It is an exchange Kissinger, a committed realist, would never have

made.

History Does Not Always Rhyme

The idea of

rapprochement with China originated with Nixon, not with Kissinger.

Nixon wrote in 1967, before he became president, that “any

American policy toward Asia must come urgently to grips with the reality of

China,” that Washington “simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside

the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and

threaten its neighbors.”

Nixon could

hypothesize about a reconciliation because Mao Zedong, China’s leader, was

interested in the same. Although Washington remained suspicious that Beijing

and Moscow were secretly coordinating, in reality the Sino-Soviet alliance had

been over since the late 1950s after sharp differences arose between Mao and

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. By the late 1960s, China and the Soviet Union

were practically at war: the combat at their northeast border around Zhenbao Island, located in the river that separated the two

states, got so intense that Mao even evacuated political leaders from Beijing

in August 1969. At the same time, China was being ravaged at home by the

excesses of the Cultural Revolution. Thus, when Kissinger first arrived in

Beijing in 1971, China was poor, isolated, dysfunctional, and fighting the

Soviets. Kissinger did not need to convince his Chinese counterparts to

distance themselves from Moscow. The former partners had already split.

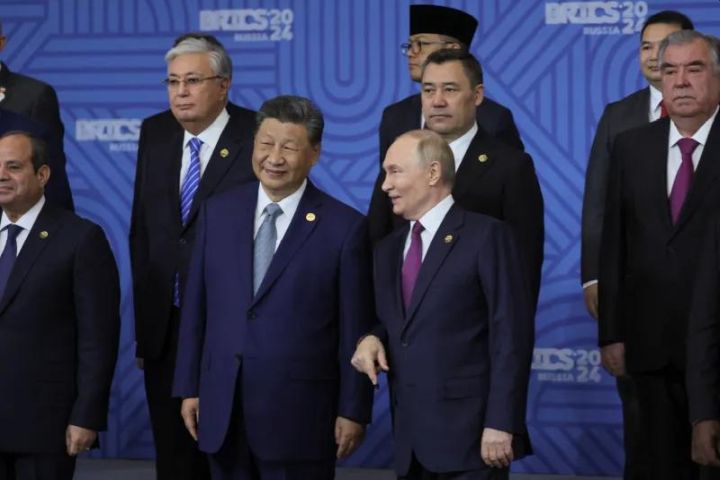

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President

Xi Jinping in Kazan, Russia, October 2024

Relations between

Russia and China today could not be more different. There is no division to

exploit. To be sure, Beijing has acted cautiously in response to Putin’s

full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022: it has abstained rather than voted

against UN resolutions condemning the war; it has never recognized Moscow’s

annexation of Ukrainian territory; it has so far declined to send complete

weapons systems to Russia; and it has carefully tiptoed around Western

sanctions. These positions have disappointed the Kremlin but did not produce a

major rift. Ultimately, what unites Putin and Xi greatly outweighs what divides

them.

The Russian and

Chinese leaders have a common vision of global politics, anchored by their

mutual commitment to autocracy and shared animosity toward the United States.

Both feel threatened by democratic countries and democratic ideas. Putin and Xi

have consistently criticized the United States for supporting “color

revolutions” in their neighborhoods and for working to contain Russian and

Chinese power in Europe and Asia, respectively. They believe the United States

presents the biggest threat to their countries’ domestic stability and external

security. In their view, Washington has far too much power in the world and has

overreached in its promotion of democracy and human rights. They want to

diminish U.S. economic, military, and political influence, as well as weaken

the liberal international order that the United States has anchored since World

War II—and they see each other as critical partners in that effort. Trump

himself may not be committed to promoting democracy or sustaining the liberal

international order, but both Putin and Xi expect that one president will not

erase decades of U.S. strategy and foreign policy tradition.

Putin and Xi do not

just want to make the world safe for autocracies; they also want to shape

international rules, norms, and institutions to make autocracy and state-led

development just as legitimate, if not more so, than democracy and capitalism.

To advance their vision, the two leaders act through various multilateral

organizations that exclude the United States, such as the ten-country grouping

called BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which count

Russia and China as founding members.

The close personal

connection between Putin and Xi facilitates and reinforces their countries’

cooperation. Putin sees Xi as his most important partner in the world, and Xi,

whose father managed the Sino-Soviet alliance under Mao, has a particular

affinity for Russia. The two leaders have met dozens of times. They like each

other—or if they do not, they are very good at faking it. Under different

leaders, the history of betrayal and distrust between Russia and China,

punctuated by Russian conquest of Chinese territory, clashing spheres of

influence, cultural differences, and border disputes, could impede bilateral

relations, but Putin and Xi’s personal ties neutralize these possible sources

of tension. As long as both men remain in power, there will be no split between

their countries.

All of this has also

enabled the rapid expansion of economic and military interests between Russia

and China. Over the past few decades, the two countries have increasingly

cooperated on energy sales, investment deals, arms transfers, defense

industrial projects, and joint military exercises. Russia’s reliance on China

has deepened significantly since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, in 2022.

In 2023, bilateral trade topped $240 billion, its highest-ever value. After

losing its European markets for oil and exports, Russia has become dependent on

revenues from energy sales to China to finance its war. Russian defense

companies receive critical components from China to build new weapons. And

China has quickly scaled up its exports of consumer goods to Russia, filling

the gap left by Western goods. According to the research firm Rhodium Group, in

the automobile sector alone, China’s market share in Russia jumped from 9

percent to 61 percent between 2021 and 2023.

A Fool’s Errand

Issuing threats of

annexation and new tariffs, Trump has muddied the waters of great-power

competition with shocking speed by antagonizing the United States’ closest

allies, especially those in Europe and North America. Trump has also tried to

court Putin by taking NATO membership for Ukraine off the table; voting with

Russia, North Korea, and other rogue states on UN resolutions regarding the war

in Ukraine; insisting that Ukraine cede territory to Russia to end the war; and

hinting at lifting sanctions on Russian companies even before a peace deal is

in place. The unnecessary alienation of allies weakens U.S. power and influence

in the world—and directly cuts against the principles of Kissinger-style

realpolitik. Trump’s eagerness to grant sweeping concessions to Putin also

signals that he considers the U.S. relationship with Russia to be more

important than ties to Ukraine or the rest of Europe.

Putin,

unsurprisingly, is already exploiting Trump’s desire for friendship. In March,

after Trump offered multiple concessions to Russia as an incentive for Putin to

sign a cease-fire agreement, Putin asked for more, including demanding that

Washington halt weapons transfers to and intelligence sharing with Ukraine and

that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky be removed from office. In private

meetings with Trump administration officials, Putin and his team may flirt with

using cooperation with the United States to balance China. But it will all be a

game. In Xi, Putin has a stable ideological, military, and economic partner. He

will not abandon that relationship for some vague promise of better relations

with the United States.

Putin’s perception of

the United States as his greatest enemy is decades in the making and unlikely

to change now. His aides and propagandists still champion the same fundamental

outlook. Although the Russian leader may believe that Trump wants closer ties,

he will not think the same about the U.S. foreign policy establishment. He

understands that the U.S. president has significant influence but not complete

control over the making of U.S. foreign policy. He saw Trump fail to deliver

tangible benefits to Moscow, such as lifting sanctions on Russia or cutting off

U.S. military aid to Ukraine, during his first term. After Putin launched his

full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the American public became even more

distrustful of the Russian autocrat. If Trump tries to peel Putin away from Xi,

strong domestic headwinds will limit his options.

Putin, moreover,

knows that Trump will be president for only four years and may have control of

Congress for only two, whereas Xi could rule China for a decade or more. With

so little U.S. support beyond Trump for a pro-Russian pivot, Putin would expect

any rapprochement to end quickly. Even Trump himself is unreliable. He is

certainly more erratic than Xi. Trump’s self-professed affinity for the North

Korean leader Kim Jong Un during his first term, for example, did not progress

beyond effusive letters and two failed summits; it produced no significant

shift in U.S.–North Korean relations.

Putin knows Trump

cannot come close to offering him as much as Xi does. Washington cannot fill

the gaps that Russia would be left with if it dropped its strategic partnership

with China. For example, the United States will not replace Chinese contracts for

Russian energy as the country is already self-sufficient. U.S. policymakers and

defense firms would also be highly reluctant to rebuild Russian military and

defense industrial capabilities. And given the losses they suffered from

previous investments in Russia, the poor rule of law in Russia today, and the

fear of renewed sanctions if Putin again invades Ukraine or another country,

U.S. private banks and companies will hesitate to reenter the Russian economy.

If Trump seems to be

making headway with Putin, Xi has cards to play to keep Russia in the fold.

China could quickly expand its fossil-fuel cooperation with Russia, such as by

finalizing the Power of Siberia 2 natural gas project, which has been delayed for

years. Beijing could also increase its assistance to Russia’s defense

industrial base. And there are plenty of ways that Beijing could tighten its

diplomatic cooperation with Russia at the UN and in key regions of shared

interest, such as the Middle East and Latin America.

A Costly Pivot

When Kissinger and

Nixon pulled China closer to the United States in the early 1970s, doing so gave

Washington leverage in its negotiations with the Soviets on arms control,

broader détente, and more. Later, following the normalization of

U.S.-Chinese relations (and Moscow’s 1979 invasion of Afghanistan), the United

States and China established a joint facility to monitor Soviet nuclear and

missile tests and started cooperating on defense. As China opened its economy

to the world in the 1980s, American businesses and consumers

benefited from the growth of China’s manufacturing sector. There are no parallel

benefits to a U.S. partnership with Russia today.

Putin and Russia have

little to offer that would serve U.S. security interests, and what they do

have, they will not use. The purpose of luring Moscow onside would

be to weaken Beijing’s position, including its ability to project military

power in its neighborhood. But Russia’s armed forces, having barely held their

own in Ukraine, cannot be expected to provide much in the way of containment of

China. Even if Russia were to build up its military, Putin would never deploy

it against China. Nor would he position additional Russian soldiers, missiles,

or ships to deter Chinese aggression in Asia.

On the diplomatic

front, Putin knows that fully realigning with the United States is off the

table. Washington’s Western partners will never agree to invite Russia to join

the European Union or NATO or even rejoin the G-7. Because of this, Moscow will

not give up the position it has now by withdrawing from BRICS, the SCO, or

other clubs anchored by Beijing. Policymakers dreaming of a new U.S.-Russian

partnership might believe that Putin could help isolate China at the UN

Security Council. This alone is not worth much to the United States, however,

since Beijing still holds a veto in that body.

Moscow cannot make

Washington a compelling economic offer, either. The United States is a net

exporter of fossil fuels and does not need additional energy imports from

Russia. Putin could extend all sorts of new investment opportunities to

American firms, but those firms have been burned before when they tried to do

business in Russia. The oil and gas company ExxonMobil, for example, signed a

multibillion-dollar joint venture with the Russian state-owned energy company

Rosneft, only to have it end after Putin invaded Ukraine in 2022. Cautionary

tales abound of American businesspeople struggling to protect their property

rights and, at times, their personal freedom amid the lawlessness of the

Russian system. A diplomatic thaw, then, is unlikely to yield significant

material benefits any time soon.

As the negotiations

over a cease-fire in Ukraine have already shown, Putin has no interest in

giving up anything for free or even after receiving significant concessions. He

would certainly demand a lot from Washington to pivot away from Beijing.

Handing Russia control of all of Ukraine would be one of them. Pulling U.S.

soldiers out of Europe and weakening, perhaps even abandoning, NATO could be

another. Having signed a new defense treaty with North Korea in 2024, Putin

could even ask for changes to U.S. military deployments in South Korea, which

Trump had already explored during his first term.

Pursuing closer

relations with Russia would come at a high cost for the United States’

relationships with its more trustworthy and capable partners. A complete

embrace of Moscow would send shockwaves through U.S. allies in Europe and Asia,

further undermining the credibility of those alliances at a time when many

countries are already concerned about U.S. commitments. Allies might stop

buying U.S. weapons, cease sharing intelligence, and reduce their trade with

and investment in the United States. European countries could even create a new

alliance that excludes Washington. Some non-nuclear countries, especially in

Asia, might decide to build their own nuclear arsenals if they see tightening

U.S.-Russian ties as an indication that the United States no longer prioritizes

the security of countries under its nuclear umbrella.

Ultimately, trying to

peel Russia away from China is both imprudent and wrong. It would be imprudent,

above all, because it would hand Putin a dangerous amount of power. Moscow

would become the pivot player in the competition between Beijing and Washington,

with ties to both and space to maneuver to its advantage. The United States

would be solving one of Putin’s core geopolitical problems: his excessive

reliance on China and limited leverage with Beijing. Making nice with Moscow

would also be wrong. It would mean endorsing Putin’s abhorrent, violent actions

both in Ukraine and at home, where he has deepened his dictatorship by

arresting protesters, activists, and opposition leaders, including Alexei

Navalny, Putin’s most formidable political opponent, whose death in a Russian

penal colony last year raised suspicions of Kremlin involvement. Embracing such

a leader is not worth the limited gains of using him to balance against China.

The sooner U.S. policymakers realize that this strategy will not work, the better

for both U.S. interests and the integrity of American values.

For updates click hompage here