By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

For The Russian Economy To Grow

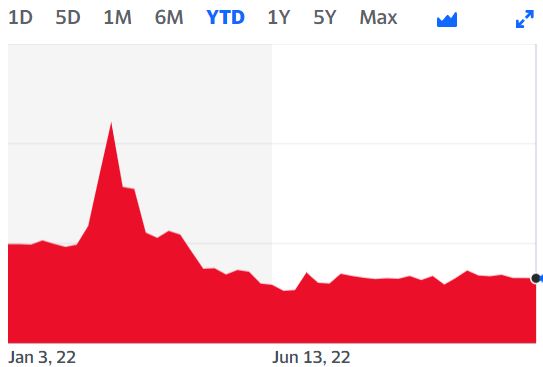

After Russia invaded Ukraine

in February, the Russian economy seemed destined for a nosedive. International

sanctions threatened to strangle the economy, leading to a plunge in the value

of the ruble and Russian financial markets. Every day Russians appeared poised

for privation.

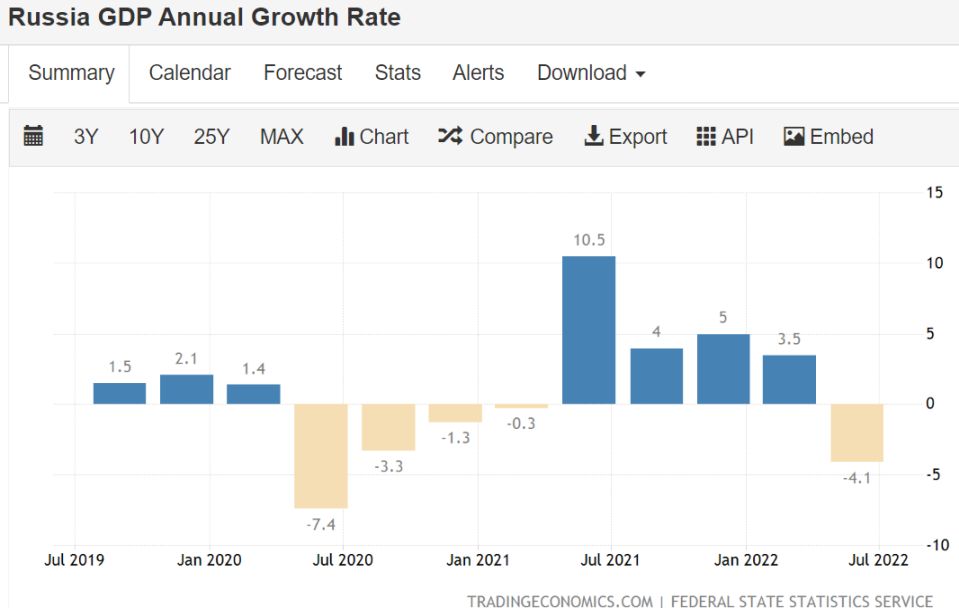

More than eight

months into the war, this scenario has yet to come to pass. Indeed, some data

suggest that the opposite is accurate, and the Russian economy is doing fine.

The ruble has strengthened against the dollar, and although the Russian GDP has

shrunk, the contraction may be limited to less than three percent in 2022.

However, look behind

the moderate GDP contraction and inflation figures, and it becomes evident that

the damage is severe: the Russian economy is destined for an extended period of

stagnation. The state was already interfering in the private sector before the

war. That tendency has become more pronounced and threatens to stifle

innovation and market efficiency further. The only way to preserve the

viability of the Russian economy is either through significant reforms—which

are not in the offing—or an institutional disruption similar to the one that

occurred with the fall of the Soviet Union.

The misapprehension

of what sanctions against Russia would accomplish can be partly explained by

unrealistic expectations of what economic measures can do. Simply put, they are

not the equivalent of a missile strike. In the long run, sanctions can weaken

the economy and lower GDP. But in the short run, the most one can reasonably

hope for is a massive fall in Russia's imports. It is only natural that the

ruble strengthens rather than weakens as the demand for dollars and euros

drops. And as the money that would have been spent on imports is redirected

toward domestic production, GDP should rise rather than fall. The effects of

sanctions on consumption and quality of life take longer to work through the

economy.

At the beginning of

the war, in February and early March, Russians rushed to buy dollars and euros

to protect themselves against a potential plunge in the ruble. Over the next

eight months, with Russian losses in Ukraine mounting, they bought even more.

Usually, this would have caused a significant devaluation of the ruble because

when people buy foreign currency, the ruble plunges. Because of sanctions,

however, companies that imported goods before the war stopped purchasing

currency to finance these imports. As a result, imports fell by 40

percent in the spring. One consequence was that the ruble strengthened against

the dollar. In short, it was not that sanctions did not work.

On the contrary,

their short-term effect on imports was unexpectedly strong. Such a fall in

imports was not expected. If Russia's central bank had anticipated such a

massive fall, it would not have introduced severe restrictions on dollar

deposits in March to prevent a collapse in the ruble's value.

Economic sanctions

did, of course, have other immediate effects. Curbing Russia's access to

microelectronics, chips, and semiconductors made the production of cars and

aircraft almost impossible. From March to August, Russian car manufacturing

fell by an astonishing 90 percent, and the drop in aircraft production was

similar. The same holds for the production of weapons, which is understandably

a top priority for the government. Expectations that new trade routes through

China, Turkey, and other countries not part of the sanctions regime would

compensate for the loss of Western imports have been proved wrong. The

abnormally strong ruble signals that back-door import channels are not working.

If imports flowed into Russia through hidden channels, importers would have bought

dollars, sending the ruble down. Without these critical imports, the long-term

health of Russia's high-tech industry is dire.

Even more

consequential than Western technology sanctions is that Russia is unmistakably

entering a period in which political cronies are solidifying their hold over

the private sector. This has been a long time in the making. After the 2008

global financial crisis hit Russia harder than any other G20 country, Russian

President Vladimir Putin essentially nationalized large enterprises. In some

cases, he placed them under direct government control; in other cases, he put

them under the purview of state banks. To stay in the government's good graces,

these companies have been expected to maintain a surplus of workers on their

payrolls. Even enterprises that remained private have, in essence, been

prohibited from firing employees. This did provide the Russian people with

economic security—at least for the time being—and that stability is a critical

part of Putin's compact with his constituents. But an economy where enterprises

cannot modernize, restructure, and fire employees to boost profits will

stagnate. Not surprisingly, Russia's GDP growth from 2009 to 2021 averaged 0.8

percent per year, lower than the period in the 1970s and 1980s that preceded

the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Even before the war,

Russian businesses faced regulations that deprived them of investment. Advanced

industries such as energy, transportation, and communication—those that would

have benefited the most from foreign technology and investment—faced the most

significant restrictions. Companies operating in this space were forced to

maintain close ties with government officials and bureaucrats to survive. In

exchange, these government protectors ensured that these businesses faced no

competition. They outlawed foreign investment, passed laws that put onerous

burdens on foreigners doing business in Russia, and opened investigations

against companies operating without government protection. The result was that

government officials, military generals, and high-ranking bureaucrats—many of

them Putin's friends—became multimillionaires. In contrast, ordinary Russians'

living standards have not improved in the past decade.

Since the beginning

of the war, the government has tightened its grip on the private sector even

further. Starting in March, the Kremlin rolled out laws and regulations that

allowed the government to shut down businesses, dictate production decisions,

and set prices for manufactured goods. The mass mobilization of military

recruits in September provides Putin with another cudgel to wield over Russian

businesses to preserve their workforces. Company leaders must bargain with

government officials to ensure their employees are exempt from conscription.

To be sure, the

Russian economy has long operated under a government stranglehold. But Putin's

most recent moves are taking this control to a new level. As the economists

Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny have argued,

decentralized corruption is the one thing worse than corruption. It's bad

enough when a corrupt central government demands bribes; it is even worse when

several different government offices compete for handouts. Indeed, the high

growth rates of Putin's first office decade were partly due to how he

centralized power in the Kremlin, snuffing out competing predators such as

oligarchs operating outside the government's fold. However, the emphasis on

creating private armies and regional volunteer battalions for his war against

Ukraine is building new power centers. That means that decentralized corruption

will almost certainly resurface in Russia.

That could create a

dynamic reminiscent of the 1990s when Russian business owners relied on private

security, mafia ties, and corrupt officials to maintain control of newly

privatized enterprises. Criminal gangs employing veterans of the Russian war in

Afghanistan offered "protection" to the highest bidder or plundered

profitable businesses. The mercenary groups that Putin created to fight in

Ukraine will play the same role.

A Long Road Ahead

Russia could still

eke out a victory in Ukraine. It's unclear what winning would look like;

perhaps permanent occupation of a few ruined Ukrainian cities would be packaged

as a triumph. Alternatively, Russia could lose the war, an outcome that would

make it more likely that Putin would lose power. A new reformist government

could take over and withdraw troops, consider reparations, and negotiate a

lifting of trade sanctions.

No matter the

outcome, however, Russia will emerge from the war, with its government

exercising authority over the private sector to an extent that is unprecedented

anywhere in the world aside from Cuba and North Korea. The Russian government

will be omnipresent yet simultaneously not strong enough to protect businesses

from mafia groups consisting of demobilized soldiers armed with weapons they

acquired during the war. Particularly at first, they will target the most

profitable enterprises, both at the national and local levels.

For the Russian

economy to grow, it will need major institutional reforms and the kind of clean

slate Russia left in 1991. The collapse of the Soviet state made institutions

of that era irrelevant. A long and painful process of building new

institutions, increasing state capacity, and reducing corruption followed—until

Putin came to power and eventually dismantled market institutions and built his

system of patronage. The lesson is grim: even if Putin loses control and a

successor ushers in significant reforms, it will take at least a decade for

Russia to return to the levels of private-sector production and quality of life

the country experienced just a year ago. Such are the consequences of a

disastrous, misguided war.

For updates click hompage here