The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its

consequences in Russia Part Three

Description of

persons involved.

Russia’s disastrous

performance in World War

I was one of the primary causes of the Russian Revolution

of 1917, which swept aside the Romanov dynasty and

installed a government that was eager to end the fighting. The Treaty of

Brest-Litovsk (1918) whereby Russia yielded large

portions of its territory to Germany

caused a breach

between the Bolsheviks (Communists)

and the Left

Socialist Revolutionaries, who thereupon left the coalition. In the next

months, there was a marked drawing together of two main groups of Russian

opponents of Lenin: (1) the non-Bolshevik left, who had been finally alienated

from Lenin by his dissolution of the Constituent Assembly,

and (2) the rightist whites,

whose main asset was the Volunteer Army in the Kuban steppes. This army, which

had survived great hardships in the winter of 1917–18 and which came under the

command of Gen. Anton I.

Denikin (April 1918), was now a fine fighting force, though small in

numbers.

The Anti-Bolshevik Underground

As we have seen in

part one and two a first attempt by America and the

Allies to mount a coup against Lenin and install their own dictator in Russia

was quit for 1917 when a planned Cossack coup failed. But the Plot itself was

still alive. As we will see in part three, it simply segued into 1918. DeWitt

Poole was still leading the charge for the United States, and he would soon be

joined by new players, new armies, and new infusions of cash.

As for finding new

local recruits, the political reality of 1918 was that Russia had been

radicalized as a result of the tumultuous events of 1917. Whereby the

disastrous effect upon Russia's political parties of 1917, then, led to the

formation of several right-left inter-party groups. The so-called Union of

Regeneration hereby combined a number of left-wing parties and the National

Centre with a more right-wing orientation however went their separate ways in

June 1918, with the UR heading east and the National Centre moving to South

Russia, suggests that there was too little faith in this alliance formed

between the two groups and that each hoped that they would be the more

successful. The National Centre, after leaving Moscow, concerned itself with

the Volunteer Army and seemed to be not particularly interested in the fortunes

of the UR in its attempts to arrange a state conference that would create an

all-Russian government according to the plans made in Moscow. For their part,

members of the UR probably thought that an Allied an incursion into Russia via

Arkhangelsk would help them to create a new eastern front, behind which would

be the SR-heartland of the Upper Volga, and that the success of this

intervention would give them hegemony in the anti-Bolshevik camp. Had the two

organizations acted in a more unified manner, they might have had more success.

As it was, the

efforts of the UR appeared to many (particularly in Siberia) as another attempt

by SRs to subjugate all to their party. The potential strength of the two

allied groups, then, never came to fruition as a result of this `go it alone'

strategy, and before either organization even began work, they had made a

crucial mistake: allowing the geographical distance between the two

anti-Bolshevik zones to assume an even greater significance than could have

been the case.

On March 3, 1918,

Lenin signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, American consulates in Russia were

ordered to step up their delivery of information to the State Department. But

in this time of war and civil war, cable service was often unreliable. Poole

told Francis that the Alexandrov cable was slow and “fearfully overloaded,”

with a capacity of only 30,000 words per day. Also, service was often

interrupted by electrical storms and by the Soviet government, which could pull

the plug on a customer any time they wanted.

Unauthorized copies

of ciphered telegraph messages sent by the U.S. consulate in Moscow were

secretly delivered to Soviet “code artists” in Room 205 of the Hotel Metropol,

the capital’s answer to the Ritz in Paris, occupied lately for more proletarian

purposes than candlelit dinners.1 Codebreakers at the Metropol tried to

decipher the telegrams and report the findings to the Bolshevik government.

Sending a cable

“directly” to Washington sometimes meant pursuing a path of telegraph relay

stations around the world, only to see it show up at the State Department a

month late wireless stations bypassed British censors who controlled underwater

cable service to America.

On April 4, 1916, Lanzing had created the Bureau of Secret Intelligence. An

extralegal agency it would have access to information from the War Department,

the Office of Naval Intelligence, the Secret Service, and whatever other

domestic or foreign agencies that were in a mood to help out.7 The BSI’s home

staff was made up heavily of Treasury agents and postal inspectors. They were

among the most highly trained federal agents in America. The Bureau of Secret

Intelligence, code-named U-1, was a clearinghouse for intelligence reports

coming in from overseas.

And although Poole

and Kalamatiano were not Bureau of Secret

Intelligence agents directly, they did work for the State Department, and their

reports went through Polk and the BSI to Lansing and Wilson. So did reports

turned in by other State Department operatives and their Russian agents. That

made them all-important intelligence sources for the BSI.

Pictured below Leland

Harrison was director of the State Department’s Bureau of Secret Intelligence,

the predecessor to the CIA and NSA:

Poole’s operatives

developed informants throughout Russia and Ukraine. Kalamatiano

was his main field officer and recruiter. Kal’s agents included around thirty

men and women who provided political, military, agricultural, financial, and

economic reports.2 Kal condensed the reports into “bulletins” that he sent to

Poole in Moscow. Poole shared them with Consul General Roger Culver Tredwell

and commercial attaché Huntington, both in Petrograd, along with Ambassador

Francis and French and British officials.

The establishment of

Poole’s networks leaves no doubt as to his importance to U.S. intelligence in

Russia. In just a few months he had moved up from a simple consul to the

control officer for dozens of spies. In Russia, he was known as America’s chefagent (German for chief agent, or spymaster).

Lenin was going to

sign a separate peace with Germany and take Russia out of the war. The Allies

(including even the Left Socialist Revolutionaries)

were stunned.

Lockhart conferred with

Foreign Office officials and the British War Cabinet. Then after American Red

Cross Colonel Thompson stopped in London on his way back to America, Lockhart

was summoned to No. 10 Downing Street. Prime Minister Lloyd George informed

Bruce that he had been chosen by King George and Alfred Milner, an ardent

imperialist in the cabinet, for a special mission.

“I have just had a

most surprising talk with an American Red Cross colonel named Thompson, who

tells me of the Russian situation,” Lloyd George was quoted as telling

Lockhart. “I do not know whether he is right, but I know that our people are

wrong. They have missed the situation. You are being sent as a special

commissioner to Russia, with power… I want you to find a man there named

Robins, who was put in command by this man Thompson. Find out what he is doing

with this Soviet government. Look it over carefully. If you think what he is

doing is sound, do for Britain what he is trying to do for America. That seems,

on the whole, the best lookout on this complex situation… Go to it.”

Lockhart was sent as an “unofficial agent” assigned to

pursue “unofficial relations” with the new Soviet government.8 He had cipher

privileges through the Moscow consulate and was supposed to be protected by

diplomatic immunity. In time, that immunity would be severely tested.

Russia’s losses at

Brest-Litovsk confirmed what President Wilson feared would happen: Europe was

getting chopped up by the belligerents, and the fighting wasn’t even over.

Borders were moved, nationalities shifted around like cattle. People in one

country suddenly found themselves belonging to another country where they

didn’t even speak the language.

But a more immediate

problem was that Germany was still camped out on Russia’s doorstep, even though

they had temporarily stopped advancing. Aside from the military threat,

Germany’s presence challenged the Western powers that had an eye on Russia’s

economic resources. Post-war Russia could turn out to be one of the world’s

biggest markets for consumer goods. Germany wanted control of those Russian

shoppers just as the Western nations did. Even if Germany lost the war in the

west, look at what the Fatherland could have in the east.

Meanwhile, the main

American operatives in Russia working on the 1918 Plot were in place, Francis,

Poole, and Kalamatiano, and their Russian agents,

along with Huntington, Judson, Brigadier General William Voorhees Judson head

of the American military mission.

A British spy plotter arrives

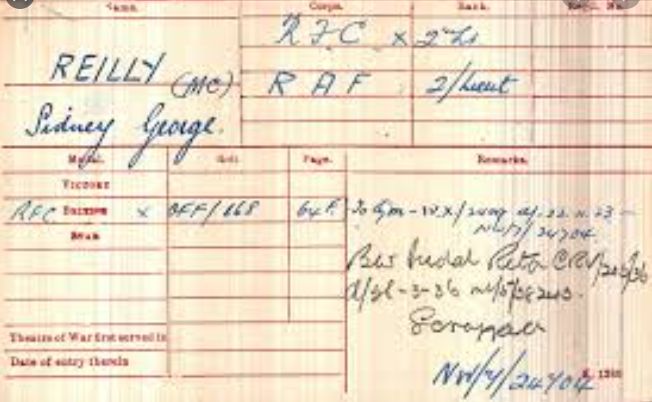

When Sidney Reilly

arrived in Moscow he was wearing the uniform of a British air lieutenant. He really

had been commissioned in the Royal Flying Corps as a volunteer at Toronto the

year before, but was not under RFC command in Russia.1

Although the Allies

were fighting an undeclared war against the Soviets in the summer of 1918,

ordered by the Allied Supreme Command and carried out by Western spies and

surrogate armies such as the Czech Legion and Savinkov’s underground force, the public face the Allies

wore in Russia was different. The Allies claimed that they kept their

embassies, consulates, and military missions open in Russia to help the Soviets

repel German invaders. That is if Lenin and Trotsky ever decided to do that.

Hence, operating openly in a British uniform and carrying legitimate military

credentials offered Reilly a measure of protection.

Reilly’s destination

on the sweltering afternoon of May 7, 1918, was a fearful one. He was on his

way to the Kremlin, the ancient brick fortress in Moscow that was now the seat

of the Soviet government.

A hot sweltering day

it was, he knocked on one of the gates and announced to the guards that he was

an emissary from none other than British Prime Minister Lloyd George. Sidney

demanded to see Lenin at once. To his surprise, he was admitted.

They signed him in as

“Relli.” Reilly was met by Vladimir Dmitrevich Bonch-Bruyevich, Lenin’s personal secretary and close

friend. Bonch-Bruyevich already knew Sidney. They had

met through a mutual friend, Alexander Ivanovich Grammatikov,

a Petrograd book collector who had once been Reilly’s lawyer. He also used to

be a Bolshevik but was now secretly a Social Revolutionary.

Bonch-Bruyevich and Reilly had a talk. Just as Lloyd George had sent

Lockhart to Russia because he didn’t trust Ambassador Buchanan’s reports, now

Whitehall was dissatisfied with some of the conflicting opinions they’d

received from Bruce about what to do about the Soviets. Reilly was London’s new

flashlight in the dark, at least as far as the British Secret Service was

concerned.

“My superiors clung

to the opinion that Russia might still be brought to her right mind in the

matter of her obligations to the Allies,” Reilly wrote later. “Agents from

France and the United States were already in Moscow and Petrograd, working to

that end.”9

Reilly also thought

he could fulfill his mission best if he worked alone and developed his own

agents.10 But Reilly couldn’t get past Bonch-Bruyevich.

After a brief talk, Vladimir Dmitrevich got rid of

Sidney. Then shortly after 6 P.M., Bruce Lockhart answered the phone in his

office. Lev Mikhailovich Karakhan, a deputy in the

commissariat of foreign affairs, was on the line. He wanted Lockhart to come

see him. He had an extraordinary story to share.

When they sat down to

talk, Karakhan told Lockhart about the audacious

appearance of this fellow called Relli. Was he really a British officer on a

diplomatic mission? Or an imposter?

“I was non-plussed,”

Lockhart recalled, “and holding it impossible that the man could have any

official standing, I nearly blurted out that he must be a Russian masquerading

as an Englishman, or else a madman.” (There was an old saying about mad dogs

and Englishmen in the noonday sun.)

Bruce told Karakhan he would check on the matter and get back to him.

Lockhart then returned to his office and called in Ernest Boyce. Boyce was

technically head of the British Secret Service in Russia but would soon find

that London’s new man in town intended to usurp his authority. “Relli” was

Sidney Reilly, Boyce said, and he really was from the SIS. That evening,

Lockhart summoned Reilly.11 When Sidney arrived, he corrected a few details of

the story Bruce had heard, but otherwise confirmed it.

“The sheer audacity

of the man took my breath away,” Lockhart said. “Although he was years older

than me, I dressed him down like a schoolmaster and threatened to have him sent

home. He took his wigging humbly but calmly and was so ingenious in his excuses

that in the end he made me laugh.”12

Reilly took his

reprimand patiently because Lockhart worked for a different ministry and had no

authority over him. Nor could Boyce touch Reilly, since Sidney had been sent by

the SIS chief himself. As far as Sidney was concerned, he was now the head of British

intelligence in Russia, whether Lockhart and Boyce liked it or not. He would

work with them as the spring and summer progressed, but right now he had his

own operations to pursue.

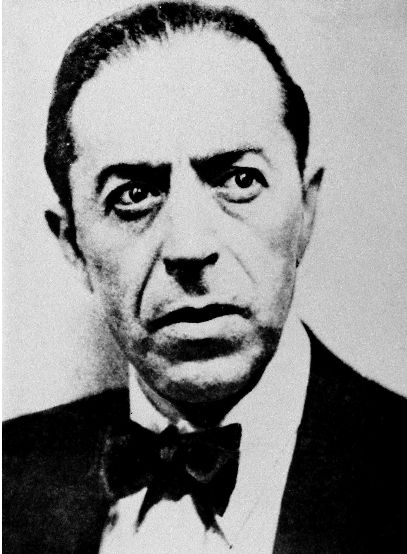

Sidney Reilly seen here pictured during a later

occasion:

Allied spy's and the Cheka

For Allied spies,

their main problem was the Cheka, the Emergency All-Russian Commission for

Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage. It was created in late 1917 by Lenin

to liquidate his political enemies. (The latter words of the title were changed

in 1918 to Profiting and Corruption.) The name was commonly abbreviated to VCheka, or simply Cheka. But some people liked to say that che’ka was the sound made when a Chekist cocked his Mauser

pistol.

The Cheka had two

branches, political, and criminal. The criminal branch was made of former

municipal police detectives, who in tsarist days had been known as agenturi, or fileri. They wore

suits and handled routine police work and answered the calls that came even in

time of civil war, arson, robberies, murders, kidnappings. Uniformed officers

had formerly been called gendarmes, though some people used the traditional

term, blue archangels, or simply, blues. The Bolsheviks changed the name of the

police to “militia.”

The political branch

was the dreaded secret police. They tracked down enemies of the party, a

category that included everybody from nosy newspaper reporters to foreign

spies. Some of them were experienced holdovers from the Okhrana. Some were

Germans, who had a reputation for efficiency and discipline. The old hands wore

suits and were more quietly efficient than the younger recruits who strutted

about in leather caps and jackets, khaki trousers, and brogans, with pistols

tucked into their waistbands.

After the Russian

Civil War, Soviet intelligence and counterintelligence officers would pride

themselves on being nondescript. They wore suits and ties. They shaved. They

got haircuts. They were no more tough-looking than anybody else you saw on the

street. Under Dzerzhinsky, though, a menacing appearance was de rigueur for a

headhunter. That included a heavy beard stubble. All Bolsheviks who weren’t at

a top-level were supposed to look shoddy, DeWitt Poole later wrote. “I suppose

they had to shave occasionally. I don’t know what they did after shaving,

probably laid up at home for a day so that they could grow a stubble.”7

The Cheka relied

heavily on informants. That might be the waiter serving you tea in a café, the

schoolteacher living next door to you, the woman driving your streetcar.

Informants wore jackets, dresses, municipal uniforms, work clothes, or student

attire, all looking invisibly Russian. In return for their services, their

internal passports announced they were Cheka “collaborators.” That allowed them

to pass through checkpoints and to break up in lines. This widespread use of

citizen informants would serve as the model for Hitler’s Gestapo, Mussolini’s

OVRA, and the East German Stasi.

Xenophon Kalamatiano (or Kal as he preferred to be called) and other

Allied operatives in Russia had to watch for such informants as they made their

rounds collecting information. They had to be suspicious of everyone, including

people they thought they knew. Agents got turned all the time. And double

agents, today known as moles, were sent in to infiltrate the networks. That’s

why the cells were compartmentalized.

Kal recruited agents

by using his social and business connections. He undoubtedly picked up

additional prospects from the consulate. But he had to be especially cautious

of volunteers. Walk-in offering information might turn out to be an agent

provocateur sent by the Cheka. Another source of danger was journalists skilled

at eavesdropping on conversations that were supposed to be secret. One of those

listeners would soon contribute to a catastrophe for the Allied plotters.

One of Kalamatiano’s most valuable military informants seems to

have been Colonel Alexander Vladimirovich Friede, head of Red Army

communications in Moscow. Friede was a Latvian who was secretly anti-Communist.

He made copies of incoming military traffic and sent them by courier to Kalamatiano and British agent Sidney Reilly.

On a higher level, French

colleagues working with Poole and ambassador Francis included General Jean

Lavergne, chief of the French military mission to Russia; Joseph-Fernand

Grenard, consul general in Moscow; and Ambassador Joseph Noulens.

At one point, Poole told Francis that he

and Lavergne were working “along the line of action that you [the ambassador]

have recommended.” Poole said that Lavergne and a General Romé

“were deeply impressed with the need for immediate action, counting each day

lost as a threat to the process of any military operations we may eventually

undertake.”8

Paris was

particularly keen to overthrow the Soviets because French investors lost 13

billion francs when Lenin repudiated tsarist debts in February 1918.9

The money had been

invested in bonds purchased by French citizens (that allegedly were backed by

the Gold held by the Russian Czar) to finance the war and maintain a

Franco-Russian alliance against Germany. Now France wanted her money back.

Deposing the Soviets and seizing control of the Russian economy would go a long

way toward paying that debt. Kalamatiano’s closest

French street associate was Martial-Marie-Henri de Verthamon.

De Verthamon was sent to Russia in early 1918 as a saboteur to

work against both the Soviets and the Central Powers.

Russian historian

Yuliya Mikhailovna Galkina wrote that he was a small

man, a cigar smoker whose black hair and mustache matched his black trenchcoat and cap. He chose “Monsieur Henri” as his code

name, which left French ambassador Noulens in

despair.

The ambassador was

also irked that de Verthamon insisted on operating

independently of the French military mission in Russia. But that was Henri’s

style. He didn’t trust anybody’s headquarters; they would be under surveillance

by the opposition. He preferred a portable office. He could move it from his

apartment to a park or a quiet café down a side street somewhere. He sent in

his reports and stayed away from missions, embassies, and consulates.

De Verthamon was thirty-seven when he arrived in Kyiv on March

22, 1918. He spoke no Russian and had to rely on the two French naval

lieutenants who worked with him. He was fluent in Spanish, though, and carried

a Spanish passport. He and his co-conspirators claimed they were Spanish

refugees fleeing the war. Once they got to Ukraine they set about poisoning

grain supplies the Bolsheviks had promised to Germany after Brest-Litovsk.

Henri then went to Moscow in May and used “the military tact of old France” to

recruit former tsarist officers for his spy network. He’s credited with blowing

up a Soviet power plant, three railroad bridges, and some ammunition dumps and

oil wells.10

Monsieur Henri also

worked with military attaché Pierre Laurent, who used to be the liaison between

the French mission and the provisional government’s Russian Revolutionary Army

and who was now spying against the Soviets. Laurent possibly supplied de Verthamon with the explosives he used. Poole said he later

gave false passports to some French and British spies to smuggle them out of

Russia. He said they had been poisoning food supplies in Ukraine, so they might

have included de Verthamon’s team.11 Another French

spy available to Kalamatiano was Captain Charles

Adolphe Faux-Pas Bidet (https://www.ouest-france.fr/europe/russie/charles-adolphe-faux-pas-bidet-l-ennemi-de-trotski-5362065).

Bidet joined the French navy as a boy, and as he sailed the seven seas he

learned seven languages, including Russian. He left the navy at the age of

twenty-nine and joined the Paris Prefecture of Police in Paris in 1909. In 1914

he was assigned as a detective with the Sûreté

Nationale, the highly efficient French counterintelligence service that had

served as a model for Scotland Yard. Bidet worked the case against Mata Hari,

an exotic dancer hired to spy for the French but who was exposed as a double agent

for Berlin.

Bidet also kept an

eye on Trotsky in Paris before the war, when Lev Davidovitch was editor of an

internationalist newspaper, Nashe Slovo (Our Word).11

Trotsky later complained that Bidet watched him with a “hateful” look.

“He was distinguished

from his colleagues by an unusual roughness and brutality,” Trotsky wrote. “Our

interviews always ended in splinters.”12 Shop

Still, there seems to

have been some other kind of relationship between the two men. To keep Trotsky

from getting arrested by the tsarist secret police, Bidet deported Lev

Davidovitch to the safety of Spain. Perhaps it was an act of mercy. Perhaps

Bidet was trying to groom Trotsky as a future mole for the French. Whatever the

motivation, it would later save Bidet’s life in Moscow. Bidet was sent to

Russia in 1917 as one of France’s top spies after receiving the Legion of

Honor.13

Meanwhile, the war

continued against the Central Powers, even if Lenin had surrendered Russia.

French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, supreme Allied commander, at first advocated

cooperating with the Bolsheviks if they would stand up to the German army.

Foch’s general staff concurred. Getting into bed with the Reds that way was

simply a matter of ignoring soiled sheets in the name of expediency.

Noulens, too, showed a patient wait-and-see attitude toward

the Reds, at first. So did Louis de Robien, a twenty-six-year-old attaché at

the French embassy in Petrograd. De Robien said that if France broke with

Russia, Paris would be playing into the hands of the Germans. Then Berlin would

have a clear field to make Russia their “most rewarding of colonies.”14

After Brest-Litovsk,

Lansing instructed American diplomats in Russia to withhold contact with the

Bolsheviks. But the consuls went ahead and tried to deal with them anyway,

discreetly, for a while. “One has to,” Poole said at the time. They were the de

facto government.15

Then Poole began to

press Washington for intervention against the Soviets. But he warned that a

purely military operation would fail. It had to be accompanied by economic

relief, technical assistance with railroads, and probably some administrative

help.

“The bulk of the

Russians are generally ignorant and moved only by immediate and material

considerations,” Poole wrote in a report to Lansing. “The educated political

leaders are [Communist] party men lacking in the Western conception of

patriotism. No class has developed self-reliance, and all dislike hard work.”

Even with the goodwill of the Russian people, “we can count on very little

serious practical help from them.” Poole further wanted to reopen the Russian

fronts to keep the Germans tied down in the east.16

Trotsky did ask for

Allied help in training his new Red Army, and General Lavergne was open to the

idea. But diplomats at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Quai d’Orsay, the

mother church of old-line French diplomacy, didn’t like the idea of helping

raise an army that might turn on them. The Quai d’Orsay overruled Lavergne. The

idea of Franco-Soviet cooperation turned out to be only a brief flicker of a

candle.

British

representative Bruce Lockhart initially believed that the Allies and the

Bolsheviks could work together.’ Another member of Lockhart’s circle was the

fiercely vigorous Captain Cromie, the British naval attaché, who regarded the

Bolsheviks – indeed, all Russians – with contempt, but agreed on the tactical

need for good relations. Back in London, right-wing advisers were selling the

war cabinet a different plan. The Allies should seize the Russian ports of

Murmansk, Archangel and Vladivostok, and use them as bases to cross Russia and

– with the help of anti-Bolshevik forces – re-establish the Eastern Front. Like

the Americans in Iraq in 2003, the British had deluded themselves that they

would be welcomed as liberators by the Russian population. Patriotic Russian

soldiers, they told themselves, would be burning to resume the war against

Germany.

So far, American,

French, and British diplomats in Russia had been sharing information with one

another. America and France had spies in Russia, but the British Secret Service

had not contributed any high-level agents but that changed now when Sydney Reilly

and Bruce Lockhart joined the plot.

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences in

Russia Part One

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Two

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences in

Russia Part Four

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Five

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences in Russia Part Six

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Seven

1. DeWitt Poole to

Ambassador David R. Francis, June 21, 1918, Francis Papers.

2. Kalamatiano to Poole, undated report, courtesy of NARA. Kalamatiano smuggled this report out of prison a few weeks after

he was arrested. He probably gave it to a Norwegian consul who visited him.

3. According to the

Imperial War Museum, the RFC had become the Royal Air Force the month before

Reilly arrived in Moscow. See “Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force Family

History,” www.iwm.org.uk.

4. Sidney Reilly,

Adventures of a British Master Spy: The Memoirs of Sidney Reilly, 2014, 6–7.

5. Robert Hamilton

Bruce Lockhart, Memoirs of a British agent,2003, 273–74.

6. Lockhart, British

Agent, 273–74.

7. Poole,

“Reminiscences, of DeWitt Clinton Poole,” 1952 unpublished typescript, Columbia

Center for Oral History, Columbia University,135.

8. Poole to Francis,

May 3, 1918, Francis Papers.

9. Carley, Michael

Jabara. Revolution and Intervention: The French Government and the Russian

Civil War. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1983, 44.

10. Yuliya Mikhailovna Galkina, “To the question of the French

involvement in the Lockhart affair: Who is Henri Vertamon?”

in cleo No. 3, 2018, Institute of Humanities and

Arts, Ural Federal University, 176–86, www.academia.edu.

11.Phillipe Madelin,

Dans le secret des services: La France malade de ses espions? (Paris: Éditions

Denoël, 2007), 19, www.rackcdn.co.

12. Phillipe Madelin,

Dans le secret des services: La France malade de ses espions? (Paris: Éditions

Denoël, 2007), 19, http://www.rackcdn.co.

13. Nicolas Skopinski,

“Charles Adolphe Faux-Pas Bidet, l’ennemi de Trotski,” Ouest-France, November

6, 2017, http://www.ouest-france.fr.

14 Louis de Robien,

The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia, 1917–1918, trans. by Camilla Sykes (New

York: Praeger, 1970), 149.

15. Poole,

“Reminiscences,” 175.

For updates

click homepage here