By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its

consequences in Russia Part Four

Description of

persons involved.

As pointed out the

Anti-Bolshevik Underground in Revolutionary Russia to a large part indeed

hinged on the extensive involvement of Allied interventionist forces, to form

an anti-Bolshevik and anti-German front in the wake of the signature of the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Thus during the late

winter of 1917, the Allies’ ambitious, improbable plan matured some of it

partly based on luck or as Ian C. D. Moffat typified it in his 2015 book 'Chaos'.

Thus afraid by a

German encroachment, on 1 March 1918, the Murmansk government informed

Petrograd that they wanted to accept the Allied offer to assist in the defense

of the city. The Soviets acting on a positive reply by Trotsky placed regional

military authority into the hands of a council-controlled by Allied officers.

Defense of the port passed to the Allied forces with Russian cooperation. On 6

March, marines from HMS Glory landed in Murmansk. On 10 March that same year

Georgy Chicherin who served as People's Commissar for

Foreign Affairs told the British representative in Moskau that the Bolsheviks

were not concerned with Allied actions in North Russia and would try to expel

the Allies from Murmansk. This attitude changed when on 7 June news of a German-backed

enemy force approaching the railway junction at Kem reached Murmansk. The

Murmansk government then acted on its own and authorized the Allies to proceed

against the enemy. On 23 June over a thousand British troops commanded by

General Maynard, arrived at the port, but as agreed at a War Cabinet meeting,

the men remained aboard ship, for the moment. But when Chicherin

protested, on 28 June the Murmansk Presidium voted to ignore Moscow's orders,

and two days later officially broke with Moscow. And thus by now the intelligence-operations

which were meant to guarantee and safeguard communications capability became a

military incursion. This act heralded the

start of the Allied military build-up in North Russia.

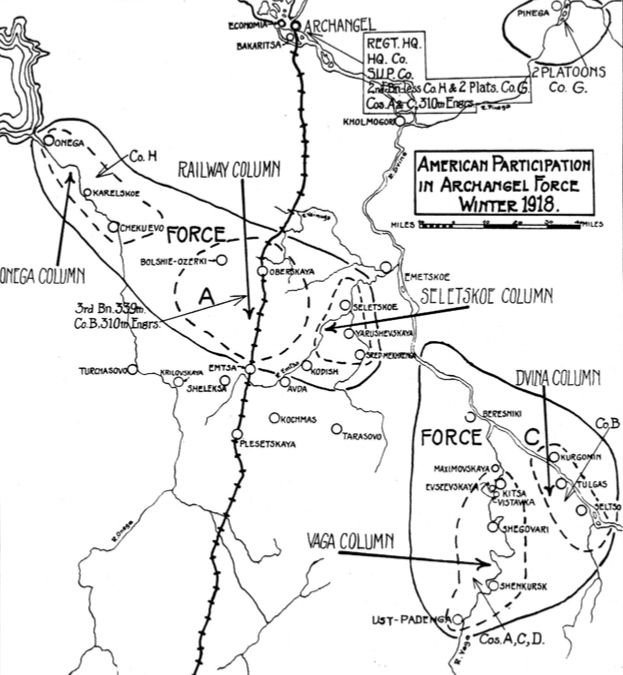

Firstly, Japanese and

Allied soldiers would seize Vladivostok (which in fact they did on April 5,

against Bolshevik wishes) and then head west along the Siberian Railway.

Secondly, British and Allied troops would

occupy Murmansk and then travel south to take Archangel.

Thus when the

Bolsheviks changed their minds about scuttling Russia’s Baltic fleet, and the

Allies changed their minds about waiting for an invitation to occupy Murmansk

and Vladivostok, not yet in Archangel), it split those that had opposed

uninvited Allied intervention, and those that wanted it to be in co-operation

with the Bolsheviks. In his heart, Lockhart believed the latter arguments too,

but he had begun to waver. Denis Garstin (who knew

Russia from before the war) had written

the previous year that “England needs Russia just as much as Russia needs

England”; who in February 1918 had found the Soviet diplomat Alexandra

Kollontai (Коллонтай) “charming . . . she bowled me over”; and who still judged

Lenin to be “the biggest force I’ve ever felt in my life,” nevertheless, had

begun to waver too: “If you look at what the Bolsheviks want to do you feel

sympathetic,” he wrote, “but if you look at what they’ve done, you’re dead

against them.”1

The not-quite

like-but similarly-minded Journalist Arthur Ransome summarized their argument

in a pamphlet which he wrote at white-hot speed for the Red Cross colonel to

bring with him: On Behalf of Russia: An Open Letter to America.2

On May 14, Raymond Robins set out from Moscow via the

Siberian Railway, with the pamphlet, Lenin’s blessing, and the Bolshevik

leader’s signed laissez-passer to speed his train.3 He carried, too, Lenin’s

invitation to the American government to dispatch an Economic Commission to his

country to explore trade possibilities. He reached Vladivostok in good time and

in good spirits, although noting the Allied occupation of the port with

disapproval, and sailed for home on June 2. “The headlands of Asia fade from

view,” he wrote in his diary that night; “the only sound is the sweep of the

surging sea, the stars shine out, the way ahead is blue-black, and the Russian

tale is told and I have had my day!!!”

When the Red Cross

colonel arrived in America he met with senators, cabinet ministers, labor

leaders, and other leading figures, and experienced a rude shock. Almost

everyone in the US disapproved of his message. The president, upon whom he

pinned his hopes, remained inaccessible and silent while advocates of

intervention in Russia worked on him. Finally, on August 4, Wilson let it be

known that Japanese forces could march east after all, so long as US troops

accompanied them. He made no mention of Lenin’s invitation concerning

Russo-American trade. “The long trail is ended,” a bitter Robins finally

admitted to himself in his diary. “So finishes the great adventure.”4

As for Lockhart and

the remainder of his group back in Russia, it was full speed ahead for intervention now. Garstin first put into words to Whitehall the plan they had

begun to contemplate. On May 10, the young captain reported by a cable that he

had just “been approached secretly by two large organizations of the old army.”

They promised to mobilize near Nizhnii Novgorod, east

of Moscow as soon as the Allies took Vologda and secured the railheads of the

Archangel and Siberian Railways. Then they would launch the counter-revolution.

That he and Lockhart had weighed and

decided they approved of the offer before sending it seems evident, since Garstin recommended that London dispatch the same number of

Allied troops from Archangel to Vologda as Lockhart had suggested in earlier

telegrams: “at least two divisions.”5

Garstin was dabbling in counter-revolution here.6 So was

Captain Francis Cromie, the man once celebrated for his ability to reconcile

Bolshevik sailors and their Tsarist officers and now scheming to destroy

Russia’s Baltic fleet. And so too was Britain’s previous leading champion of

Anglo-Bolshevik cooperation, Robert Bruce Lockhart. No doubt they both shared Garstin’s reservations about the Bolsheviks. But the truth

is that, also, all three of them believed that in conspiring against the regime

they were doing what the British government wanted them to do. And this was

decisive. And instead of the dovish, more sober Robins and Ransome, they

consulted with men who had been in the counter-revolutionary camp all along.

This included the

French ambassador to Russia, Josef Noulens who

dominated the community of foreign diplomats still in Russia.7

Noulens shared the visceral anti-communism of the Quai

d’Orsay in Paris (the French Foreign Office). Although in March he once had

encouraged Trotsky to resist German invasion by promising French support, in

reality, he had always hated the Bolsheviks and never really believed France

could find common ground with them, not even against Germany. Bolshevism

threatened French business and financial interests in Russia. But, said Noulens, “We shall not be allowing any further socialist

experiments in Russia,” said Noulens.8

From April 1918

onward, following directions from Paris with which he completely agreed, he did

his best to help nearly every anti-Bolshevik schemer who approached him. In the

past, Lockhart had ridiculed him for his reactionary views. Now the British agent

followed in the Frenchman’s footsteps. Noulens, he

acknowledged, “commenced to finance and support these [counter-revolutionary]

organizations before I did.”9

But Lockhart was

primed now to collaborate with Noulens and the

others. On May 14, he bade farewell to Raymond Robins at a Moscow railway

station. Then, on May 15, the day after seeing off his erstwhile friend and

ally, he met “an agent sent to me by Boris Savinkoff

[sic].”

Boris Savinkov redux

Boris Viktorovich

Savinkov (Russian: Бори́с Ви́кторович Са́винков) that he

was the Scarlet Pimpernel of the Russian Revolution, had he not also been a stone-cold killer.

This son of a judge

was a poet, a novelist, a chain-smoking morphine addict, and the former head of

the prewar Socialist Revolutionary Party’s “Fighting Organization.”10 He had

been a terrorist during the Tsarist period. The Tsar’s courts convicted him of

complicity in the 1904 assassination of Russia’s Minister of the Interior,

Vyacheslav Plehve, but as with so many of their

prisoners, failed to hold him after they caught him. Free to follow his

ruthless inclinations, Savinkov had planned or taken part in thirty-two

additional killings, or at least so rumor had it.

In 1917, he served

for a brief period as Kerensky’s Assistant Minister of War, but then supported

General Kornilov’s abortive right-wing uprising against him. When the

Bolsheviks took power, he fled to the Don region, to contact the

counter-revolutionary Volunteer Army of Generals Alexeyev and Kornilov. The

latter two despised each other, as noted above, but they despised Savinkov

more. Alexeyev wrote to Lockhart that he would rather cooperate with Lenin and

Trotsky.11 No sooner had Savinkov arrived in the White Army camp than someone

tried to assassinate him. Not surprisingly, he returned to Moscow, dove

underground and, independent of Alexeyev, with whom despite everything he

nevertheless remained in touch, began to plan an anti-Bolshevik rising.

Moscow was by then an

anti-Bolshevik hothouse, as Lockhart was beginning to appreciate. A “Right

Center,” of counter-revolutionary monarchists, right-wing Kadets and other

conservatives, had pro-German leanings. A counter-revolutionary “Left Center”

of liberal Kadets and various anti-Bolshevik socialists favored the Allies.

Savinkov entered neither body but encouraged them to combine in a “National

Center,” which eventually they did, although without ever relinquishing their

distrust for each other. The great conspirator refused to join but recruited

from this body, and promised to cooperate with it. Meantime he was organizing

his own Union for Defense of the Motherland and Freedom (UDMF). When he

contacted Lockhart, he had between two thousand and five thousand men under his

command.12 He had spies shadowing Lenin and Trotsky, preparing to assassinate

them. And he had begun to plan a rising in three towns north of Moscow to

coincide with the Allied intervention “on a large scale” that Lockhart’s new

ally, ambassador Noulens, already had encouraged him

to believe would take place in late June or early July.13

Lockhart reported to

London on his meeting with Savinkov’s representative, and added: “With your

approval I propose to continue to maintain an informal connection with [him]

through third parties.” The Foreign Office did approve. Lockhart would be safe

enough: he is “so much identified with Bolsheviks that he is hardly likely to

be suspect,” noted one mandarin. Sir George Russell Clerk, a more senior and

experienced official, added more cagily still: “I believe that the Bolsheviks

know pretty well everything that goes on. I am not quite sure of our cyphers,

and I am confident that unless Mr. Lockhart gets direct instructions to the

contrary he will continue to keep in touch with Savinkoff

[sic]. I should therefore leave this unanswered for the present.”14

Cagey, yes; but Clerk

had set a precedent that would have significant consequences. At the end of

May, Lockhart took note that the Foreign Office remained silent on Savinkov,

and understood, quite correctly, that it meant for him to maintain the

connection. In the middle of August, at a crossroads again, and with the

Foreign Office again incommunicado, he not unreasonably drew a similar

conclusion and plunged into even deeper waters, this time with fatal results.

Boris Savinkov might

have received money from the United States. In May or June 1918, Xenophon Kalamatiano reportedly met with a Russian agent linked to

the SRs. On June 27, Kal reported to DeWitt Poole that this man’s group planned

to mount an uprising two weeks later to turn out the Soviet government. That

would coincide with the July revolts that Savinkov planned.

Savinkov could have

received payments from Washington through an American official in Europe such

as Oliver T. Crosby. He was a U.S. Treasury special representative in Paris who

had been assigned to pay Kaledin with U.S. funds

laundered by Paris and London. Czech intelligence reportedly contacted Crosby

on April 27, 1918, to inquire about the “promised funds” that Kal should have

raised for them through British agent Sidney Reilly.

If Kalamatiano could get funds for the Czechs, he likely could

have obtained cash for Savinkov.

But Boris testified

at his 1924 trial in Moscow that his attacks on the Soviets were financed by

French Ambassador Joseph Noulens and the Czechs. No

available evidence, though, indicates whether that money had originally come

from Washington.

The plan called for

Savinkov’s army to seize Yaroslavl, Rybinsk,

Kostroma, and Murman. French forces would advance the short distance from

Archangel to take Vologda themselves. Vologda was important because it was the

largest town south of Archangel on the rail line down to Moscow. Vologda was

designated the link-up point for American, French, British, and Czech forces

that would then join Savinkov’s army and march on the capital.

Savinkov said the

French had advance knowledge that left-wing Socialist

Revolutionaries were planning their own Moscow uprising, and Savinkov’s

attacks in the Upper Volga should coincide with that, though he would not be

cooperating with the Left SRs.

Lockhart now,

self-confident and determined as ever, although pursuing a program

diametrically opposed to his initial one, he embarked upon a series of

dangerous, clandestine meetings, often accompanied by the equally fearless

Grenard. “I am in touch with practically everyone,” he reported to London on 23

May.15

Through Lieutenant

Laurence Webster, an intelligence agent acting as Passport Control Officer in

Moscow, he engineered a series of meetings with two leaders of the Moscow

Center, Professor Peter Struve, a former Kadet, and Michael Feodoroff,

a former Tsarist minister, both now supporters of General Alexeyev.16 He also

established links with counter-revolutionary right Socialist-Revolutionaries,

to whom he gave money.17 Quickly he realized that the Moscow hothouse was

planning something big. Where previously he would have talked things over with

Robins and Ransome (who might have acted as restraining influences), now he

talked to Reilly, Garstin, and Cromie, and to Noulens, and Grenard and DeWitt Clinton Poole. They all

favored the forward policy.

Lockhart engaged

Captain Cromie in discussions about the destruction of Russia’s fleet in the

Baltic Sea. Britain’s naval attaché lived in the Petrograd hothouse rather than

the Moscow one and, as soon became apparent, he was doing more than dabble in

counter-revolution there. Where first Cromie had wanted to destroy Russia’s

Baltic fleet so Germany could not have additional ships, now he wanted to

destroy Bolshevism so Germany could not have Russia. Already he was “the moving

spirit” among a group of Petrograd anti-Bolshevik activists, including other

Allied officials and members of Savinkov’s UDMF. They often met near the docks

not far from the British embassy at a Latvian social club (of which more later)

that catered to sailors and their officers.17 These Petrograd conspirators had

a pipeline funneling White volunteers north to Archangel. They had Russian and

British agents already in situ planning to overthrow its Bolshevik-dominated

Soviet with the help of those volunteers, just as Poole’s occupying forces

(“not less than two divisions,” Cromie also stipulated, no doubt after

consultation with Lockhart)18 arrived from Murmansk.19 Then they would

establish a White counter-revolutionary Volunteer Army in Archangel to

accompany Poole’s troops when these marched upon Vologda, and onward to aid

Savinkov when he launched his insurrection. In other words, Cromie and the

Petrograd hothouse knew what the Moscow hothouse was planning and intended to

help.20 Lockhart decided to help too.

As we will see

Latvians and their Rifle Brigade were to determine the shape and then the

outcome of most of the conspiracies and internal eruptions that convulsed

Russia for the rest of the year. It was troops from the brigade, led by Captain

Eduard Berzin, who crushed the revolt of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries in

July, after they murdered the German ambassador. Meanwhile, the Allied

conspiracy, now managed by an erratic caucus of Lockhart, Cromie, Reilly and

the French ambassador, Joseph Noulens, was in chaos.

They had assumed that the British force at Archangel, under General Frederick

Poole, would advance south to seize the junction town of Vologda. His march was

supposed to be timed to support counter-revolutionary risings in towns nearer

Moscow, launched by their fanatical fellow plotter Boris Savinkov, who was

involved in several attempted risings against the Bolsheviks. Unfortunately,

General Poole failed to tell them that he had decided to postpone his offensive

(he had previously requested reinforcements in the form of a brass band from

Britain – jolly good for recruitment). As a result, Savinkov’s insurrections

took place but were suppressed by the Red Army after brutal street-fighting.

Lockhart did not

despair, though he now knew that Poole’s force was far too small to defeat the

Red Army. ‘Determined, competitive, hard-nosed, capable and supremely

confident, he set out to recoup the situation,’ Schneer writes. He began by

hurling money around. He gave Savinkov’s clandestine National Centre a million roubles in cash, and planned – with a French colleague – to

raise this to 81 million (nearly £60 million in today’s money). Then he began

to think about the Latvians. How loyal were the soldiers of the Rifle Brigade

to Bolshevism, now that the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had allowed the Germans to

overrun Latvia? How loyal, indeed, were they to Russia as opposed to their own

country? Could they be persuaded at least to move out of Poole’s way? In

Petrograd Cromie was recruiting Latvian seamen for his own plot to disable

Russia’s Baltic fleet, while Reilly was saying: ‘If I could buy the Letts, my

task would be easy.’ Lockhart began to look for disillusioned members of the

Rifle Brigade.

Just when the

Bolsheviks became aware of the plot isn’t clear from Schneer’s book. But they

surely assumed its existence even before it took shape. Nothing was more

inevitable than that the envoys of the ‘bourgeois imperialist Entente’ would

look for ways to subvert a communist revolution and incite its opponents to

rebel. The Cheka kept a close eye on the consulates and embassies in Moscow and

Petrograd, noticing that counter-revolutionary leaders were using them as

sanctuaries, even as bases.

From the American

side, David R. Francis the American ambassador to Russia was a key coordinator

of the Plot. He asked Washington for 100,000 troops to take Petrograd and

Moscow in support of the coup against Lenin:

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences in

Russia Part One

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Two

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Three

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Five

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences in Russia Part Six

The 1917-18 Envoys' Plot and its consequences

in Russia Part Seven

1. Walpole, “Denis Garstin

and the Russian Revolution,” p. 598: Garstin to

?, January 18, 1918.

2. Arthur Ransome, On

Behalf of Russia: An Open Letter to America, New York, 1918, p. 27.

3. Wisconsin State

Historical Society, Robins’ Diary Entry, May 14, 1918.

4. William Hard,

Raymond Robins’ Own Story, New York, 1920, online version, Chapter V, “The

Bolshevik ‘Bomb,’” http://net.lib.byu.edu/estu/wwi/memoir/Robins/Robins5.htm

5. Oxford University,

New Bodleian Library (OUNBL), Milner Collection, Dep. 109, Box B, Lockhart to

Foreign Office, May 10, 1918.

6. Walpole, quoting

letters dated May 15, 1917, February 14, 1918, and July 17, 1918.

7. Michael Jabara

Carley, “The Origins of the French Intervention in the Russian Civil War,” The

Journal of Modern History, Vol. 48, No. 3 (September 1976), pp. 413–39

8. Victor Serge, Year

One of the Russian Revolution, 2015, p. 231.

9. John W. Long,

"Plot and counter-plot in revolutionary Russia: Chronicling the Bruce

Lockhart conspiracy, 1918, Intelligence and National Security, Volume 10, 1995

- Issue 1

10. Winston

Churchill, Great Contemporaries, London, 1937, p. 103.

11. R H Bruce

Lockhart, British Agent,1933,p. 288.

12. Winston

Churchill, Great Contemporaries.

13. The National

Archives, London (TNA), WO 106/1186, Summary of telegrams on Russia; for

Savinkov more generally, see, especially, Richard Spence, Boris Savinkov,

Boulder, CO, 1991. For the promise to Savinkov made by Noulens,

see University of Indiana, Lilly Library, UILL, Lockhart Collection, Bruce

Lockhart, “The Counter-Revolutionary Forces,” p. 4. For just how complicated

this counter-revolutionary world really was, see Jonathan Smele,

The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, 1916–26, London, 2015.

14. TNA, FO 371/3332,

Lockhart to Foreign Office, and notes on file, May 15, 1918.

16. TNA, FO 371/3313,

Lockhart to Foreign Office, May 23, 1918.

17. TNA, FO 371/3348,

Bruce Lockhart, “Secret and Confidential Memorandum on the alleged ‘Allied

Conspiracy’ in Russia,” November 5, 1918, p. 1.

18. They alleged it

at the 1922 trial of right SRs. See N. V. Krylenko, Sudebnye

rechi. Izbrannoe, Moscow, Iuridicheskaia literature, 1964, pp. 157–8.

19. G. E. Chaplin, “Dva perevorota na Severe (1918),” Beloe delo: letoopis’ Beloi bor’by, vol. 4 (Berlin: Mednyi vsadnik, 1928), p. 14.

This is an extract of the autobiography in Russian of G. E. Chaplin, who took

part in the events discussed above (translation provided by Andrey Shylakhter). See also Benjamin Wells, “The Union of

Regeneration: The Anti-Bolshevik Underground in Revolutionary Russia, 1917–19,”

DPhil thesis, Queen Mary College, University of London, 2004, p. 62.

20. TNA, ADM

137/1731, Cromie to Admiralty, June 14, 1918.

For updates click homepage here