By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

While a lot has been

written about the British and Dutch missions in Qing

China, during Russian Imperial times, it was the 1727 Treaty of Kyakhta which gave Russia privileges no other European

country enjoyed until the Opium Wars, which was the result of a conscious Qing

attempt to forestall a Russo-Junghar alliance. It

worked admirably well. Conciliated by trade, for several decades Russia made no

further significant effort to interfere in Inner Asian politics.1

The first diplomatic

crisis in Russo-Qing relations began after the Qing conquest of the Dzungar Khanate in 1755-57. The Dzungar–Qing

Wars were a decades-long series of conflicts that pitted the Dzungar Khanate against the Qing dynasty of China and their

Mongolian vassals. Fighting took place over a wide swath of Inner Asia, from

present-day central and eastern Mongolia to Tibet, Qinghai, and Xinjiang

regions of present-day China. Qing victories ultimately led to the

incorporation of Outer Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang into the Qing Empire.

Between the

mid-seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries, China and its borderlands

figured prominently in the dreamworld of Western geopolitics. Access to its

trade held the key to untold commercial riches. The seeming success of Catholic

missionaries at the imperial court made the augmentation of Christ’s flock by

hundreds of millions of Chinese converts appear to be an imminent prospect.2

For Russians, military dominance over the Qing held the promise of wealth and

security for Siberia, in the near term, and eventually hegemony in Eurasia and

in the Pacific. The Amur valley, a territory which Muscovy formally ceded to

the Qing in the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk after military reverses, was regarded

by influential Russians as a lost Eldorado whose supposed agricultural

productivity and easy access to the ocean could have given economic meaning to

all of the empire’s eastern conquests, from Irkutsk to Alaska.3

In 1754, the

prominent official Fedor Soimonov, soon to be

governor of Siberia, arrived in Nerchinsk to prepare ships and personnel for a

voyage down the Amur River and into the North Pacific. This was envisioned as a

Third Kamchatka Expedition, following in the footsteps of Vitus Bering’s

earlier explorations. Russian officials had come to regard the Amur as crucial

to their plans for the exploration and exploitation of fur-bearing territories

in northeastern Siberia, the Pacific islands, and eventually Alaska. Without

it, goods and supplies needed to be moved to the oceanic port of Okhotsk

through the Stanovoi and Iablonovoi

Mountains, a dangerous and ruinously expensive portage that precluded the

building of large vessels. Anything that could not be carried by a donkey or

packhorse was out of the question; anchors, for instance, had first to be

divided into five parts.18 In 1756, Vasilii Bratishchev

was sent to Beijing to negotiate with the Qing court for permission to

sail down the river; at the same time, the letter from the College of

Foreign Affairs he carried contained the pointed insinuation that the

expedition was not to be abandoned in the event of Qing reluctance. According

to a secret intelligence report Irkutsk governor-general Ivan Iakobii received from the Catholic missionary

Sigismondo di San Nicola in Beijing, Qianlong had read the diplomatic letter Bratishchev brought and exclaimed, “Cunning Russia asks

respectfully [to navigate the Amur] but announces that it has already prepared

ships for the voyage, by which they imply that they will sail with or without

permission.” Permission was denied, in part, San Nicola reported, because of a

desire to protect the pearl fishery in the Manchus’ ancestral domains.4

Anticipating a

rejection, the prominent official Fedor Soimonov had

been ready to sail down the Amur in force, but the College of Foreign Affairs

found his proposal foolhardy and rejected it. Plans for the expedition were put

on hold indefinitely. Soon, however, the tone of diplomatic exchanges became

more hostile in the wake of Qing allegations that Russia was violating the

Treaty of Kiakhta. The new empress Catherine II began

to revisit the prospect of a military solution, which had first been proposed

by Iakobii in the 1750s.

The diplomatic and

military escalation and impasse thus came to constitute a kind of Cold War,

albeit one with lower stakes. Intelligence and other forms of covert action

substituted for military engagement and direct negotiation.

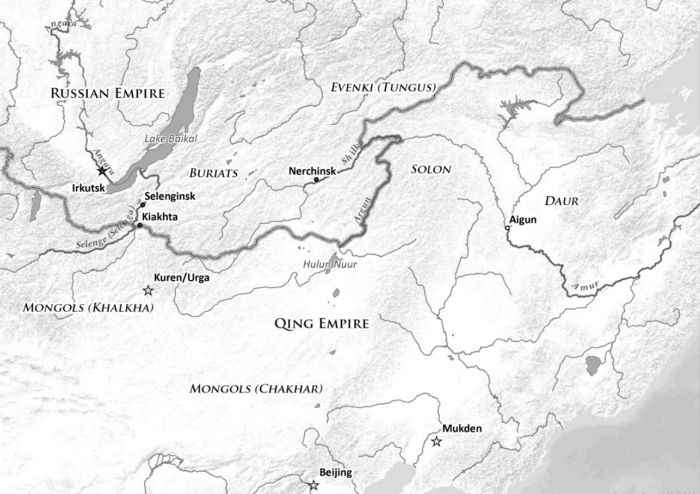

Intelligence and knowledge

Here it was that

intelligence and other forms of covert action substituted for military

engagement and direct negotiation. The Russo-Qing Cold War played out

principally in two theaters: the mountains and steppes around the former Junghar Khanate, where the borders of modern Russia,

Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and China meet, and the border regions east of Lake

Baikal, including northern Mongolia and Manchuria. They were never isolated

from each other. Russian officials stationed in each theater routinely shared information

and strategic deliberations, with Iakobii in his

nominally insignificant town of Selenginsk serving as

the key node for the collection and dissemination of intelligence along the

entire Russo-Qing frontier; on the other hand, Qing armies and command staff

sent to Xinjiang frequently included Khalkha Mongols or members of Solon, Daur,

and other Manchurian tribes.5

And although it was

intended as a kind of the moral equivalent of war, advancing imperial goals in

the absence of credible military or diplomatic force, by the end of fifteen

years of increasingly intensive penetration of Qing Mongolia Russia was no closer

to achieving these goals than it had been at the outset. In the meantime, the

forces that had once so threatened Qing rule in Mongolia now foreclosed the

possibility of a Russian takeover. As the fourth emperor of the

Qing, Ch’ien-lung, put it, rejecting the prospect of an invasion of

Russia: “If the Russians wished to cause trouble they would have done so long

ago when Chingünjav and the Khalkhas

were in confusion and wavering … Since they did not move in the past, they

certainly will not cause trouble now.”6 It would be nearly a century before

Russian ships sailed down the Amur, which would require a brazen annexation

during the Second Opium War, and Mongolia would remain firmly in Qing hands

until the twentieth century. Indeed, perhaps the most valuable information

Russia received from its spies was the constant reassurance that the Qing were

not plotting an offensive and that it was, therefore, free to concentrate its

attention on military events in Europe and on its southern frontier.

In 1763, the Siberian

historian Gerhard Friedrich Müller prepared a memorandum considering the

justifications for war: the “insults and contempt” shown by the Lifanyuan, he argued, provided ample grounds to renew

pre-Nerchinsk Russian claims on the Amur and Mongolia. Müller argued that the

conquest of the frontier would be easier than it seemed at first glance: vastly

outnumbered by resentful Han Chinese subjects and facing discontent from

Mongols who would abandon it for Russia at the first opportunity, the Qing

Dynasty would, if not collapse like a house of cards, at least be easily pushed

into an advantageous peace.

Qianlong, for his

part, had also considered war: he still maintained some claims over the region

east of Lake Baikal and its Buriat and Evenki

population (relatives of the Manchus and Mongols), and a Mongol spy reported to

Iakobii in 1760 that a military council on the

subject had taken place. According to the agent, the Qing generals were wary of

the climactic difficulties of Siberian warfare and the uncertainties

surrounding the Russian response.23 Qianlong himself was reluctant to attack

unless the war could be won at a single blow. Thus neither party took any

meaningful steps towards shattering the peace between the two empires, and

Russia never committed to the required buildup of troops. In 1764, at the

height of the tension, Russian military reforms increased the border’s

theoretical complement of troops by a factor of two, but this was phrased in

purely defensive terms and would, in any case, fall far short of the numbers

needed for an invasion.

The diplomatic and

military escalation and impasse thus came to constitute a kind of Cold War,

albeit one with lower stakes. Intelligence and other forms of covert action

substituted for military engagement and direct negotiation. As in the twentieth

century, when neither side wanted to risk open rupture, the struggle for the

loyalties of third parties became increasingly crucial. This role was played by

the Eurasian peoples caught between the two empires. In the mid-1750s, the

Khalkha leaders of Qing Mongolia were corresponding with Iakobii

about defection, the Kazakh Middle Horde and the Uriangkhai

of the Altai Mountains were swearing fealty to both sides, and Junghar fugitives were demanding asylum in Russia in the

tens of thousands. By the end of the period in 1771, most of the Volga Torghuts (Kalmyks), Western Mongols like the Oirats who dominated the Junghar

Khanate, some of whom had been Russian subjects since the 1630s and others who

had recently fled the Qing conquest, defected across the border in a dramatic

migration famously chronicled by Thomas De Quincey.7

The Macartney embassy

The creasing belief

that Britain was Russia’s main enemy in the Pacific appears to be misleading,

in fact over the next few decades, it would be the Americans, not the British,

who would take the leading role in the emerging maritime fur trade between Canton

and northwestern North America.8

This is when high

officials of the French empire and others, started to rely on intelligence

about the Russo-Qing relationship as they thought the Russians were about to

invade the Qing realm and overthrow the dynasty.

Following Russia's

1792 expedition to Japan (when they received trade concessions from the

Tokugawa shogunate) at the time when it also had made leeway in China, the

Russians now looked with concern on the British embassy

in the Chinese capital headed by (the former British ambassador in St.

Petersburg) George Macartney who had been deputed by the government in London

to request ‘fair and equitable’ trading rights from the Qianlong Emperor.

Thus the fear of the

British threat, by the end of 1791 led Russia to developed a secret,

conspiratorial plan to derail the Macartney embassy by poisoning the well in

Beijing and describe the potential options as follows:

1. To send to

Beijing, under the pretext of border disputes, a smart, humble, and resourceful

man; to send with him some scholars, to disabuse the Chinese of the idea that

we are all Kropotovs, who unfortunately gave them a

very poor sense of our degree of enlightenment. Beyond this, a few Jesuits, in

their ordinary civil capacity, who by means of their brethren located in

Beijing, may be quite useful. Through them, he must secretly persuade the

Chinese Government of the danger to which it will be subject if it once allows

the English into their ports, by depicting their behavior in India, the

destruction of the most beautiful domains of the Great Mogul, and that they

have equal aims in mind for China, and so on. The 2nd means consisted in this,

that before dispatching the minister, two Jesuits should be sent with news of

this enterprise, who can meanwhile preemptively discover who in the Chinese

ministry supports the English, and can underhandedly give them to know of the

hostile plans of the English against their state as a matter known full well in

Europe.9

This was followed by

the 1805 Golovkin embassy, Alexander I’s attempt to one-up Macartney by

extracting commercial concessions like those the British

envoy had failed to obtain during his 1793 embassy.

Several members of

the embassy had associated intelligence-gathering functions,

including the academics, but it seems clear that the unofficial head of

intelligence was 27-year-old Count Iakov Lambert, son of the French émigré

Henri-Joseph de Lambert and the embassy’s second secretary. In preparation for

departure, Lambert collected all the existing documents he could find in the

central archives having to do with RussoQing

relations. In addition to Lambert, the embassy also employed the best Qing

experts in the empire. Like Macartney, Golovkin took his intellectual

preparation seriously; unlike him, he would not be caught unawares by Inner

Asian politics.

In the wake of the Golovkin

debacle, Russia tried to use the next rotating shift of the Russian

Ecclesiastical Mission to gather intelligence, particularly about French and

British attempts to deal with the Qing, and make contact with the former

Beijing Jesuits. In 1807, the mission’s escorting agent Semën

Pervushin was issued a set of instructions which gave

him detailed guidance for conversations with the missionaries. Beyond being

merely cautious of possible British influence and bribery, in conversations

with ex-Jesuits, the agent would “observing exterior calm, subtly extract

needed information, and not immediately or suddenly so that they may not guess

at what you need.” He was provided with a few sample conversational scenarios

as illustration.113 Though it is likely the Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not

know this, a register of all the Beijing ex-Jesuits would be brief indeed: by

this point only Frs. Poirot, de Grammont, and Panzi

remained among the living and were unlikely to be of much use or

influence.

The Golovkin embassy

however had longer-term consequences. In 1816, Macartney/William Amherst’s

embassy failed in part because Qing officials imitated Yundondorji’s

precedent in demanding that he kowtow not just in Beijing, but in advance of

his audience. Both sides explicitly invoked Golovkin in the process.10

The geopolitical

environment of the region however was shaped not by the scientific achievements

of the explorers who traversed it, but by the mistaken assumptions, failures of

knowledge, and outright deceptions on the basis of which European powers took

action. It was an environment riddled with paradoxes. An age of intelligence

failure became an age of conspiratorial obsession; Britain, so long represented

as the spearpoint of European imperialism in China, depending on intelligence

about Russia; Russia, despite its long history of intelligence, gathering in

the Qing Empire, was just as susceptible to strategic ignorance as Britain and

France. These paradoxes should reshape our understanding of the period. If an

outsize personality like the Hungarian adventurer Maurice

Benyovszky was able to keep the entire foreign-policy apparatus of

France spellbound by false information, it was not because the events he

revealed were marginal or unimportant, but because European ignorance was so

profound.

The Russian

intelligence structure never succeeded in creating a self-enclosed world of

discourse, in which the terms, as well as the objects of study, were determined

by the needs and categories of power. Indeed, the reason it was developed so

assiduously was that Russians could not but confront the strength and regional

influence of their competitor. Moreover, it was too frequently disturbed by the

human lives of the people on which it relied. Mongols made for convenient

informants, except when they knew how valuable they were and tried to make the

most of their position; missionaries might have been well-placed sources, but

the violent, liquor-soaked world they made for themselves turned them from a

solution into a problem. It was only when the Russian state managed to sever

nearly all the links connecting it informationally with the Qing that it began

to indulge fantasies of global power centered on the North Pacific, listening

far more closely to projectors in St. Petersburg than to its own officers in Eastern

Siberia (who were themselves not above idle scheming). Russia’s competitors,

for their part, were seduced by the promises of privileged intelligence access

contained in putatively secret documents and published sources and pursued

policies that were doomed to failure as a result.

Conclusion

In the middle of

the seventeenth century, statesmen and scholars all over Europe looked at China

as a beacon of commercial, intellectual, and cultural potential, offering the

promise of wealth as well as global civilizational convergence. Russia’s earliest

ventures eastward became interesting to a variety of audiences as an indication

that this convergence was to be realized together with Europe’s commercial

ambitions. Just as merchants in London and Amsterdam made thousands from the

trans-Muscovite rhubarb trade, so too did agents and diplomats exploit

Muscovy’s emerging potential as a source of sinological

knowledge. Well into the eighteenth century, Western Europeans avidly sought

out rumors and documents about the war they thought was coming between

Catherine and Qianlong or the embassy they thought had established a lasting

alliance between Peter and Kangxi. By the nineteenth century, this was no

longer the case. British and American commercial vessels began to prove

definitively that Russia’s China trade was of regional rather than global

significance, and the work of its agents and missionaries became objects of

academic and not political curiosity (in contrast to Central Asia, where

Russian advances gave the initial impetus to British fantasies about the “Great

Game”).

But no significant

group of Qing subjects, whether Mongol, Turkic, or Manchurian, chose to defect

to Russia, and no unexpected conflict gave Russian border officials the pretext

to execute their ambitious strategic plans. Instead, the future of Russo-Qing

relations would depend on the problems faced in the mid-nineteenth century by

the Qing empire itself, borne out of both internal and foreign conflict. The

Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion provided the Russian Empire with the

opportunity to negotiate from a position of strength; in the case of the Second

Opium War, Russian gains, territorially the greatest of any imperialist power,

were directly based on exploiting the Qing government’s desperation. As a

strategy for gaining power, knowledge had become a dead end.

1. On this see also

Gregory Afinogenov. Spies and Scholars: Chinese

Secrets and Imperial

Russia's Quest for

World Power. Cambridge Harvard University Press, 2020.

2. The most

thorough account of the former is Louis Dermigny, La

Chine et l’Occident: le commerce à Canton au XVIIIe siècle, 1719-1833 (Paris: S.E.V.P.E.N., 1964); the

classic statement on the latter, Arnold Rowbotham, Missionary and Mandarin :

The Jesuits at the Court of China (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1942).

3. See Mark Bassin,

“Expansion and Colonialism on the Eastern Frontier: Views of Siberia and the

Far East in Pre-Petrine Russia,” Journal of Historical Geography 14, no. 1

(January 1988): 3–21, doi:10.1016/S0305-7488(88)80124-5; and for the nineteenth

century, Mark Bassin, Imperial Visions : Nationalist Imagination and

Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1999).

4. See among

others Jonathan Schlesinger, The Qing Invention of Nature: Environment and

Identity in Northeast China

and Mongolia, 1750-1850, 2012.

5. See Loretta Eumie Kim, “Marginal Constituencies: Qing Borderland

Policies and Vernacular Histories of Five Tribes on the Sino-Russian Frontier”

(Ph.D., Harvard University, 2009).

6. Lo-Shu Fu

(Compiler, Translator), Documentary Chronicle of Sino-Western Relations,

1644-1820, 1966, 238.

7. Thomas De Quincey,

Revolt of the Tartars and the English Mail-Coach (London: Bell, 1895).

8. Louis Dermigny, La

Chine et l’Occident: le commerce à Canton au XVIIIe siècle, 1719-1833 (Paris:

S.E.V.P.E.N., 1964), 1161–1198.

9. As quoted in Afinogenov, Spies and Scholars.

10. Gao Hao, 'The

Amherst embassy and British discoveries in China,' October 2014,History 99

(337) DOI: 10.1111/1468-229X.12069.

For updates click homepage here