By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Description of persons

involved

As we have seen in parts one, two, and three, one

can conclude that during the last fortnight of May 1918, the Mensheviks, Right

SRs, and Kadets all held party conferences

that rejected the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, while a Social Revolutionary appeal called for an

immediate armed uprising against the Bolsheviks.

On 18 May, some 400 Constituent Assembly deputies met together and

condemned the treaty, declaring that the state of war with the Central Powers

continued to be in place.

What is commonly known as the Russian Civil War should also rather be

seen as a whole series of

overlapping and mutually reinforcing conflicts: a rapidly escalating

struggle between the armed forces of Lenin’s Bolshevik government and its

counter-revolutionary opponents.

Another subject that led to many controversies was when Grigory Zinoviev, leader of the Comintern,

gave a speech at the meeting of the Petrograd Soviet on 1 November 1918,

where he blamed the British, who allegedly exploited its embassy building to

confer with Russian counter-revolutionaries. This was followed by an operation

that was portrayed as a polite request by the Chekists to allow the search of

the premises, in response to which Captain Cromie

(a British naval attaché who planned to sink Russia’s entire Baltic

fleet) opened gunfire, killing the group’s senior officer who had asked

him in English to cease fire and wounding three other rank-and-file before he

was fatally shot in the head.

Former Russian senior administrators used to confer at the premises of

the British Petrograd mission, secretly overseen by the Cheka agents. On 31

August, Cromie, with another MI6 officer, was holding

a confidential discussion with two double agents nicknamed Shtekel’man

(or Shtegel’man) and Sabir enlisted by the Petrograd

Cheka as early as in the spring of 1918. Apart from these individuals, more

than a dozen auxiliary personnel were staying in the building that night. But

it was Boris Savinkov (a terrorist associated with

the Socialist Revolutionary Party during

prewar years, who served as Kerensky’s Assistant Minister for War and turned to

counter-revolution after the Bolsheviks seized power) whom the Chekists most

wanted to arrest. If the senior officer of the group knew him by appearance,

other service members had no idea what Russia’s supreme political terrorist

looked like in reality.

Boris Savinkov

When Cromie confronted the attackers at the

top of the front staircase, he started shooting at the Chekists climbing the

stairs. A rash shooting, which lasted several minutes, led to tragic results: a

Cheka agent was killed by ‘friendly fire,’ while two others were gravely

wounded by Cromie, who received two bullets to the

back of the head. There could be a reason to conclude that Shtekel’man

or Sabir shot Cromie to cover the tracks of their

rapport with MI6.

Yet there are specific gaps in the understanding of the motives. For

example, did the Petrograd Chekists act on their own or the instructions from

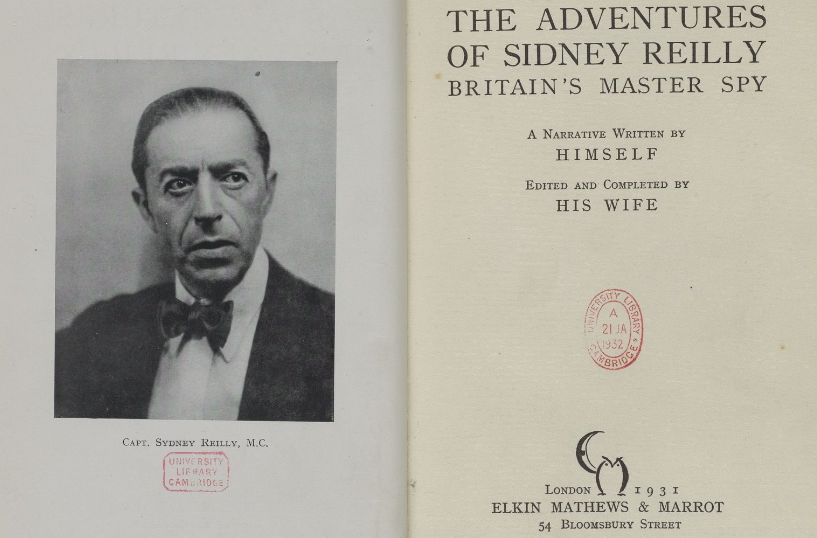

Moscow central office? Was Sidney Reilly associated with the Cheka invasion of

the mission? Could the German military intelligence be somehow involved in the

murder of Cromie to vindicate Count Mirbach’s demise?

As the embassy personnel later recalled, the Chekists turned the entire

building upside down in search of Savinkov. They

confiscated the documents, which Cromie did not

manage to destroy, and appropriated most of the fur overcoats, silverware,

books, art, and even pieces of furniture. Only the intervention of the Danish

and Dutch envoys saved the premises from complete looting.

Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks launched an unprecedented xenophobic campaign

in the press even before the official announcement of the complot. Some

newspapers published Zinoviev’s appeal, which was putatively also attacked by a

killer at the Astoria hotel in Petrograd, ‘to grant the right to workers to

lynch any intellectual right on the streets.’ Lockhart depicted some well-known

political figures such as Trotsky, Kamenev, and Radek, all urging the immediate

execution of the detained British and French citizens.

President Woodrow Wilson (seen with his wife Edith Wilson) authorized

the American war against Soviet Russia and approved a secret plot in Moscow to depose Lenin and his

government:

Soviet punitive organs on all levels enthusiastically supported the

campaign of unrestricted terror. ‘We need neither courts nor tribunals! Let the

vengeance of the workers raise; let the blood of Socialist revolutionaries and

White Guards pour out! Destroy out the enemies physically!’ – demanded the

Petrograd Pravda on 1 September 1918. Another public statement by Zinoviev

signaled an apotheosis of mass hysteria when he called for eliminating 10

percent of the Russian citizens who were dissatisfied with the Bolshevik

regime.

Charles R. Crane used his own money to finance private networks of

American agents in Russia for several U.S. presidents, including Wilson:

The plot led to the persecution and killing of British subjects in the

provinces under the Bolsheviks’ rule, including Kalamatiano

(who directed an information bureau in Russia gathering sensitive materials for

American Consul General De Witt Clinton Poole), arrested on 18 September

in front of the American consulate following his return to Moscow from the trip

to Ufa. Unable to withstand ruthless interrogations, Kalamatiano

betrayed to the tormentors a network of secret informants that the Americans

set up in Russia during the First World War.

The bloody repressions against anti-Bolshevik groups aimed at

controlling the Russian population may also be explained by the low personal

culture of many rank-and-file Chekists, combined with a messianic vision of their

chiefs who believed their sacred duty was to exterminate all ‘bourgeoise

exploiters.’ Like French Jacobins in the late eighteenth century, some of them

stated that they were guided by ‘new morality predicated upon glorious ideals

of the destruction of all violence and oppression in the world.

Following the complot’s fiasco, the witch-hunting in the Red Army and

navy led to a massive purge of all displeased with the existing regime. Those

suspected of contacting the British or French missions were immediately sacked,

arrested, and in many cases executed. As the head of the Naval General Staff

reported to Trotsky and Jacov Peters in

October 1918, the Chekists exposed and eliminated sixteen

‘Anglo-Americano-French spies,’ including the chief of the Red Army’s Main

Staff registration service, his assistant, and the director of the Red naval

military intelligence.

Bruce Lockhart’s interrogations by Peters and Lev Karakhan,

the deputy People’s commissar for foreign affairs, took place on several

occasions from 6 to 15 September at the Lubyanka central prison, wherefrom the

diplomat was later transferred to a secure apartment within the Kremlin wall.

For obvious reasons, the British and Soviet versions of these interviews

differed. If Lockhart downplayed his role in the plot to evade a harsh

sentence, the interrogators corroborated the British diplomat’s involvement in

the conspiracy, expostulating him on going to the Bolsheviks’ service.

By 20 September, the Foreign Office and the NKID had finally settled

Lockhart–Litvinov exchange together with the reciprocal deportation of their

assistants. Five days later, the Soviet representative left Aberdeen via the

Norwegian seaport of Bergen for Petrograd. In his absence, one of Litvinov’s

closest associates – Theodor Rothstein – assumed the duties of the Bolshevik

government’s representative in the UK. Accordingly, thirty-one British and

twenty-five Frenchmen, including Lockhart and Grenard, released from prison,

managed to cross the Finnish border by train to reach Stockholm on 9 October.79

Some authors credited Peters or Zakrevskaia with

Lockhart getting permission to quit Soviet Russia. Yet their motives should be

viewed as a secondary consideration. At the same time, the primary motivation

was the Bolsheviks’ objective ‘not to burn all bridges between Russia and

Britain in case their relations returned to normality someday.

The Supreme revolutionary tribunal put an end to the ‘Lockhart plot.’

Whereas Western newspapers ignored it, the Bolshevik press highlighted the

trial regularly. It took the court a week in the interim, from 25 November to 3

December 1918, to sentence six persons to death (including four people – in

absence) and ten – to prison. The court exonerated eight supposed plotters,

apparently the Cheka double-agents. Sidney Reilly managed to bypass the traps

and escaped from Russia, though the Bolshevik put a price of 100,000 roubles on his head. Merely one death sentence was

carried out – that of Aleksander Fride on 17 December

1918, while the same punishment to Kalamatiano was

later changed for a lengthy prison sentence. He was, however, released on 21

August 1921 at the request of the American Relief Administration (ARA) and

deported to the United States, where he died two years later. Strange as it may

seem, none of the Latvian officers were brought to court. As Reilly confessed

to the Chekists who interrogated him after he was finally arrested in 1925, “I

presume that Lockhart’s trial involved people who had nothing to do with me, or

on some occasions, only the remotest connection with the case.”

The ‘complot of ambassadors’ was featured in several novels and movies

in the USSR and abroad. Instantly, Lockhart was the lead character of the

Hollywood cinema blockbuster British Agent in 1934, whereas the Soviet film,

entitled Whirlwinds Hostile (Vikhri vrazhdebnye), commemorated the complot’s thirty-fifth

anniversary in 1953. On 7 March 2006, the Supreme court of the Russian

Federation refused rehabilitation of all the accused persons.

But there are still open questions, for example, how should one

evaluate the activities of British diplomatic representatives in Soviet Russia

during the summer months of 1918, and was there a real chance for the plot to

be brought to life by the foreign missions. The intervention failed mainly due

to the Bolshevik leaders’ unscrupulous diplomatic maneuvers between the warring

coalitions. At the same time, the activation of domestic

counter-revolutionaries prompted the British, French, and American governments,

as had happened before, to resort to alternative means. The combined operation

to replace the Bolshevik rule with military dictatorship could provide the

re-establishment of the Eastern front until the allies’ victory was gained. On

the other hand, remaining feckless enough to conduct an independent foreign

policy, Moscow would inevitably become a satellite of Western powers. However,

owing to a deficit of appropriate financial resources and the munitions

required by the UK for the final offensive in the summer and autumn of 1918,

most British politicians considered a large-scale armed intervention in Russia

hazardous and, therefore, useless enterprise. London and Paris bet on a coup

d’état by internal Bolsheviks’ opponents backed by the British and French

missions.

Given the general pattern of the coup, the plotters relied upon the

assistance of Latvian rifle units whom they intended to convince into

rebellion. Despite Lockhart’s inexperience in producing anti-governmental plots

and Reilly’s adventurism, the conspirators should have concentrated them to the

north of Moscow or the Volga region instead of spreading forces thinly between

different fronts. At the same time, one may conclude that the plan to rely on

the Latvians in the anti-Bolshevik uprising was challenging to carry out for

its impudent nature, exacerbated by the constant hesitance of national service

members, and, what seems even most important, the preventive actions undertaken

by the Cheka. Dzerzhinsky and Peters steered the plotters down the wrong path

with the help of double agents through the disinformation that the conspirators

received from Lubyanka central office through various channels.

Some maintain that René Marchand

came to Lubyanka to share the intelligence of the complot right after the

meeting of the Entente diplomatic and military representatives on 25 August.

Then the correspondent of the Figaro was recommended by Lenin and Dzerzhinsky

to reveal the ‘insidious intentions’ of Western representatives in the open

letter message, which had the effect of an exploding bomb. It is also clear

that two other factors played a crucial part. First, Lockhart, Reilly, and Cromie seriously underestimated the long-time experience of

the Cheka’s bosses as former ‘professional revolutionaries.’ Second, the

British diplomats and intelligence officers nourished a sense of arrogance

about their limitless organizational and financial capacity. This false

impression allowed historians to define the conspiracy as a ‘true British

plot.’ In any case, one could be led to believe that Reilly’s desire to disrupt

local authorities by conducting sabotage at numerous factories, warehouses, and

railway communications could not be brought to life.

Because of some MI6 officers, the idea to undermine the Bolshevik rule

had been converted into a full-scale plan of a military coup d’état by August

1918. Available evidence indicates that Lockhart

provided diplomatic cover and partial financing for the coup. At the same

time, Reilly and Cromie acted as its general managers

– the former in Moscow and the latter in Petrograd. As for other British

diplomats, they kept away from the conspiracy, informing London of current

developments in Russia and running only occasional errands for Lockhart,

Reilly, or Cromie.

It might be more correct to term the failed attempt to overthrow the

Bolshevik regime as the ‘general consuls’ plot.’ The British MI6 agents and

some diplomatic employees made a decisive contribution to its organization. Yet

Dzerzhinsky and Peters succeeded in catching Lockhart, Cromie,

and Reilly in the trap. The failed coup d’état led to the launching of the Red

mass terror inside Russia as well as to the beginning of the Entente’s

full-scale armed intervention against it at the end of 1918. The ill-famous

conspiracy ruined the Soviet-British relations, expelling in this way any

possible steps towards rapprochement until the spring of

1920 when the new political and economic developments made it again

possible.

Meanwhile, the NKID repeatedly informed the Allied governments of the

Bolsheviks’ readiness for negotiations. On 24 October 1918, Chicherin

addressed Wilson, and on 3 November, the People’s commissar sent a similar

request to the Entente political front-runners via neutral Sweden. Three days

later, the delegates of the Sixth All-Russian Congress of Soviets announced

their peace offer to foreign peoples and governments.

Referring to Cecil’s memorandum of the Russian situation for the

Cabinet, Buchanan described the case in the following manner:

So long as Trotsky, Lenin, and their associates retain power, we shall

never have a sufficient guarantee that German activities will cease. We must,

however, make it clear that our sole object is to free Russia from those who

have betrayed her to Germany and to prepare the way for the holding of a

Constitutional Assembly with a mandate to form a stable central government and

to organize an armed force for the maintenance of order (Buchanan to Cecil, 28

October 1918, The British National Archive, FO 800/205/406–410).

For updates click hompage here