By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

There can be no alliance between Russia and the West, either for interests

or for the sake of principles. There is not a single interest, not a single

trend in the West that does not conspire against Russia, especially her future,

and does not try to harm her. Therefore Russia’s only natural policy towards

the West must be to seek not an alliance with the Western powers but their

disunion and division. Only then will they not be hostile to us, not of course

out of conviction, but out of impotence. - Fyodor Tyutchev,

Slavophile and a militant Pan-Slavist.1

What ideas drive the Kremlin elite? What binds Russia together? During

the Soviet times, what held together the population was a mixture of ideology

and nationalism. At the beginning of the communist era, people may have

believed in Marxism-Leninism. Still, over time they became cynical as they

understood the difference between communist slogans about equality and the

dictatorship of the proletariat and the reality of a society in which the

Communist Party elite (about 8 percent of the population) lived substantially

better than those not in the party. By the time the USSR collapsed, the Soviet

official national identity was a mixture of patriotism and a belief in the

superiority of the socialist system. But it had been increasingly challenged by

Mikhail Gorbachev, the provincial Communist Party ideology secretary who rose

to become the leader of the USSR in 1985. He understood that he had to reform

the atrophied Soviet system:

Imagine a country that flies into space, launches Sputniks, creates

such a defense system, and can’t resolve the problem of women’s pantyhose.

There’s no toothpaste, no soap powder, not the necessities of life. It was

incredible and humiliating to work in such a government.2

Since the Soviet collapse, Russians have been searching for a new

identity. But after twenty-five years, there is still no consensus, and the

potential ethnic minefields are evident. What does it mean to be Russian? This

question for centuries has provoked controversy and never has been fully answered.

Is being Russian an ethnically exclusive concept? In Soviet times, the “fifth

point” in every internal Soviet passport was nationality. At age sixteen, every

citizen had to state their nationality, mainly determining their career

trajectory. Being Russian was the most desirable category and most

career-enhancing. Then came Ukrainian and other Slavic ethnicities. Being

Jewish—defined as a non-Russian nationality—often meant exclusion from the most

prestigious academic institutions or Communist Party positions. Being Kazakh,

Uzbek, Chechen, or Azeri could also be problematic. This is the exclusive

definition of being Russian: the privileged nationality in a multinational

state.

Since the Soviet collapse, there have been attempts to define

“Russianness” in a more inclusive, civic-based way—as a citizen of Russia,

irrespective of ethnicity. The government attempted in the 1990s to introduce

the inclusive term “Russian” (citizen of Russia) for Russian, as opposed to the

ethnically exclusive “Russky.” It never caught on,

and during the Putin era, the ethnically complete expression has become

mainstream. Indeed, in 2017, Putin stated that the Russian language is the

“spiritual framework” of the country, “our state language” that “cannot be

replaced with anything.”3

After seventy-four years of communist rule and the loss of the

non-Russian Soviet republics, it was unclear what Russia’s new national

identity should be or who was a Russian. So in a rather unusual move, in 1996,

Boris Yeltsin created a commission with a unique charter: to come up with a new

Russian Idea. He appointed an advisory committee headed by the Kremlin’s

assistant for political affairs, Georgii Satarov, and the government newspaper offered the

equivalent of $2,000 to the person who produced the best essay on the topic in

seven pages or less. But from the outset, the project was doomed. Satarov admitted that a national idea could not be imposed

from above but had to come from the bottom up. No one could develop an

appropriate national idea, even though one contestant won a prize for his essay

on the “principles of Russianness.” In 1997, the project was terminated.4

Trying to have a commission create a new national identity on the spot in a

fluid political transition was almost certain to fail. But a new identity is

indeed gradually emerging.

In 2007, the Kremlin backed the creation of an international

organization: Russky Mir (Russian World). Its head is

Vyacheslav Nikonov, grandson of Stalin’s long-serving

foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov, whose demeanor and equally dour

negotiating style was legendary. Nikonov, an

outspoken defender of the Kremlin and critic of the United States, has served

in the Duma and has held academic positions. His foundation is designed to

promote Russian culture and language worldwide and appeal to people who have

emigrated from Russia over the past century to return to their roots. It is

usually defined as “Russian,” inclusively anyone who speaks Russian (Russko-Yazichny) and identifies with Russian culture

irrespective of their ethnicity.

The seeming confusion about what it means to be Russian has its roots

in the origins of the Russian state. Muscovy became a consolidated state at the

same time as it began to expand and conquer adjacent territories in the

fourteenth century. It expanded (and sometimes contracted)for the next five

hundred years as the state grew stronger. It fought wars with Tatars, Livonian

knights, Poles, Swedes, Turks, and Persians—and its population constantly

became more ethnically diverse. Many “Russians” were the product of mixed

marriages with various roots. Indeed, one-third of the prerevolutionary Russian

imperial foreign ministry was staffed by Baltic Germans, ethnic Germans who

lived in the Baltic states when the Russian Empire acquired them. For instance,

in the early twentieth century, the Russian foreign minister was Count Vladimir

Lamsdorf. One of his descendants later became West

Germany’s economics minister. Russians’ sense of their own identity was also

increasingly bound up with their sense of imperial destiny, paternalistically

ruling those around them, including Ukrainians, who were known as their “little

brothers.”

Perhaps because of this ambiguity about what it meant to be Russian,

the elite grappled with the issue by focusing not so much on ethnicity but on

the uniqueness of Russian civilization. Over the years, the Russian Idea became

a powerful cornerstone of the country’s avoiding identity. Its core was “the

conviction that Russia had its own independent, self-sufficient and eminently

worthy cultural and historical tradition that sets it apart from the West and

guarantees its future flourishing.”5 Russian rulers early on defined themselves

by how they differed from Europe, stressing their Eurasian vocation. That,

rather than comparing themselves, say, to Asia, was their starting point. In

the nineteenth century, deputy minister of education and classical scholar

Count Sergei Uvarov summed up the essence of the

Russian Idea in the famous triad “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and NatIdeality.”

This is what defined the Russian state. Its three fundamental institutional

pillars were the Orthodox Church, the monarchy, and the peasant commune.

Inherent in this nineteenth-century definition of what it meant to be

Russian was the belief in the superiority of a communal, collective way of

life, as opposed to the competitive individualism of the more developed

European countries. Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, for instance, vividly portrays the

contrast between the artificial, mannered lives of the Saint Petersburg

courtiers who spoke only French to each other and the pure, simple, moral life

Levin leads on his country estate. The organic ties between the monarch, the

peasants, and the Church had little room for an emerging middle class, which

might eventually challenge the power of the absolute monarch. The peasant

commune, or mir (which also means both “world” and “peace”), formed the basis

not only of the Russian Idea but also of an incipient political system that stiIdeanfluences the way Russians view relations between

rulers and the ruled.

Harvard historian Edward Keenan elaborated on the distinctive aspects

of the Russian system, which began in medieval times and arguably persists

today. He described it in a pioneering article published just before the Soviet

collapse. He argued that the political culture of both the Russian peasant

commune and the Russian court emphasized the importance of the group over that

of the individual and discouraging risk-taking. At the court, it was important

for the boyars (nobles) to act as though they supported a strong tsar, even if

the reality was otherwise and the tsar was weak. Informal mechanisms were far

more critical than formal institutions of governance, and it was essential to

obscure the rules of the game from all but a small group of power brokers who

were privy to these rules. Moreover, foreign emissaries in Russia were

primarily kept ignorant of what was happening in court. Over centuries, the

persistence of opaque rules of the game within the Kremlin walls has made it

difficult for outsiders and foreigners to understand how Russia is ruled and

what motivates its foreign policy.6

The traditional tendency to emphasize Russia’s uniqueness also focused

on the moral and spiritual qualities of the Russian Idea. The nineteenth-century

poet Fyodr Tyutchev famousIdearote:

The notion that Russia was somehow beyond a rational understanding

became part of the image of a country that could not adhere to norms

constructed in the West.

Indeed, Russians have long been divided over whether they should look

to the West or the East. Although the Russian Idea had many adherents in the

nineteenth century, it also had opponents. Dissent and opposition have as long

a tradition in Russia as has autocracy. After Russia’s humiliating defeat by

Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire in the Crimean War in 1856, there was

growing pressure at home for reform. The serfs were emancipated in 1861, and

Tsar Alexander II created local legislative councils and reformed the

judiciary. He introduced other measures designed to give a small portion of the

population a voice in the political system. But it was not enough for those who

wanted Russia to adopt European institutions. Indeed, Alexander was

assassinated in 1881 by members of a revolutionary group seeking radical

change.

As the nineteenth century wore on, those who believed in Russia’s

unique and superior destiny—the Slavophiles—were challenged by the

Westernizers. They wanted Russia to adopt European values and institutions, the

rule of law, and greater democracy. More radical elements turned to socialism

or anarchism, but they all looked west to construct the socioeconomic model

they wanted Russia to adopt. Although successive Russian tsars, beginning with

Peter the Great, had looked to Europe as a technological and economic model

they tried to emulate, they resolutely rejected the idea of emulating Europe’s

political model because thaIdeauld have spelled the

end of Russian absolutism.8 In today’s Russia, those committed to perpetuating

Russia’s unique system and protecting their vested interests continue to battle

the minority who would like Russia to become a thoroughly modern state with the

rule of law and institutions that serve the population.

Just as Russians have been ambivalent about the West, the West has been

uncertain about—if not downright hostile toward—Russia. The scathing—and

ultimately incorrect—criticism in the Twittersphere of the shoddy state of

Russian hotels in Sochi in 2014 on the eve of the Olympics echoed many past

complaints of Russia’s backwardness. Indeed, for centuries the outside world

was generally suspicious of Russia. A series of Western travelers to Russia in

the nineteenth century described a Russia that shocked many of their readers:

backward, even barbaric, and the antithesis of what an enlightened society

should be. The French Marquis de Custine published La

Russie en 1839 after a trip

to Russia, in which he wrote:

He must have sojourned in that solitude without repose, that prison

without leisure called Russia, to feel the liberty enjoyed in other European

countries, whatever form of government they may have adopted. If your sons are

ever discontented with France, try my recipe: tell them to go to Russia. It is

a helpful journey for every foreigner; whoever has well examined that country

will be content to live anywhere else. It is always good to know that a society

exists where no happiness is possible because man cannot be happy unless he is

free by the law of nature.9

Another renowned traveler was the American George Kennan, a cousin of

the grandfather of the famous diplomat and historian George Frost Kennan.

George Kennan, the elder, traveled extensively in Russia in the nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries, producing the two-volume Siberia and the Exile System,

for which he interviewed political exiles sent to Siberia by tsarist

bureaucrats. He became a fierce critic of the repressive tsarist system but

soon became disillusioned with the Bolsheviks, writing, “The Russian leopard

has not changed its spots.… The new Bolshevik constitution… leaves all power

just where it has been for the last five years—in the hands of a small group of

self-appointed bureaucrats which the people can neither remove nor control.”10

Soviet Ideology

How have ideas influenced Russian foreign policy? And does Russia need

an ideology to guide its foreign policy? Or is nostalgia for the

nineteenth-century days when Russia was a great power to inspire today’s

Kremlin? Indeed, the current occupants of the Kremlin are fond of invoking the 1815

Congress of Vienna, when the great powers divided Europe, as a model to be

admired. Tsarist Russia’s ideological trilogy of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and

Nationality was directed mainly toward Russia’s internal evolution. There was

no official foreign policy ideology in an era when Russia became a major player

in the nineteenth-century Concert of Europe. When the Bolsheviks took power,

however, that changed. Marxism-Leninism became the official ideology with an

explicit foreign policy component. Of course, the Bolshevik leader Vladimir

Lenin took the writings of the German Karl Marx—and adapted them to the Russian

environment. Marx had been dubious that the large peasant Russia was ripe for

revolution, and Lenin had to explain it.

Nevertheless, what appeared revolutionary at the beginning increasingly

began to resemble the imperial era as time went on. “Soviet socialism turned

out to bear a remarkable resemblance to the Russian tradition it pretended to

transform.”11 This was equally true in foreign and domestic policy. Soviet

ideology blended the rhetorical aspects of Leninism with a heavy dose of

Russian nationalism. And whatever the formal doctrine, the predominant feature

of the Soviet attitude toward the international arena was a dialectical view of

the world. The USSR was against the West, which was out to defeat the Soviet

Union. Agreement with the West might be possible on a case-by-case basis, but

in the long run, the interests of Russia and the glavnyi

protivnik (main enemy) were opposed. This dialectical

view and suspicion of the outside world has been remarkably durable throughout

the reign of tsars, communist general secretaries, and post-Soviet presidents.

What was the international component of Marxism-Leninism? Ironically,

Karl Marx believed that international relations would be irrelevant once the

revolution took place. “The worker has no country,” he wrote.12 Foreign policy

was the preserve of the bourgeoisie. Once the proletariat was in power, there

would be no more national states. Of course, in Marx’s thousands of writing

pages, he said very little about the future, only the past and present. It was

left to his Russian disciple Vladimir Lenin to explain how Marx’s ideas

pertained to relations between states. Lenin’s significant contribution was his

treatise Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism, written in 1916. He

sought to explain why World War One had broken out and why it would bring about

the end of the capitalist system and the beginning of the socialist era.

Without delving into the minutiae of Lenin’s arguments, Imperialism explained

that capitalist countries would inevitably come to blows over competition for

colonies, and the proletariat in both the metropolises and the colonies would

rise to defeat their oppressors. Long after Soviet citizens had become cynical

about their ideology, this theory retained its appeal in third world

countries—and one can hear echoes of these theories in contemporary Cuba,

Zimbabwe, and Venezuela. Lenin remained a committed internationalist until his

early death in 1924, as did his would-be successor Leon Trotsky. But Trotsky

was no match for his rival, the one-time Georgian seminarian Joseph Stalin, who

defeated him in the succession struggle in the late 1920s and eventually had

him murdered with an ice pick in Mexico City in 1940.

Unlike the other Bolshevik leaders, Stalin had spent very little time

abroad, spoke no European languages, and was suspicious and resentful of his more

cosmopolitan comrades. But precisely because his rivals did not take him as

seriously as they should have, he could outmaneuver them and amass power. Once

he was securely in the Kremlin, Stalin realized the international revolution

predicted by Marx and Lenin would not happen anytime soon. So he redefined

internationalism in 1928: “An internationalist is one who unreservedly supports

the Soviet Union.” From then until the end of the USSR, Soviet ideology, under

the guise of internationalism, became increasingly nationalistic. Behind the

rhetoric was an understanding that Russian national interests should be

paramount. The Soviet Union’s Eastern European allies after 1945 should define

their appeals in terms of Moscow’s needs. During the height of Sino-Soviet

hostility, when the USSR and China engaged in a brief border war in 1969, the

struggle was explained in ideological terms. The real reason was a classical

struggle for territory, power, and influence. Therefore, by the end of the

Soviet era, very few in the Soviet elite believed in the tenets of

Marxism-Leninism. It was only when Gorbachev came to power that the USSR

officially eschewed the doctrine of the inevitable clash between communism and

capitalism and began to promote the idea of mutual interdependence.

Nevertheless, the ideal view of the world continued to influence many

officials—including a mid-level KGB officer working

in Dresden in the late 1980s.

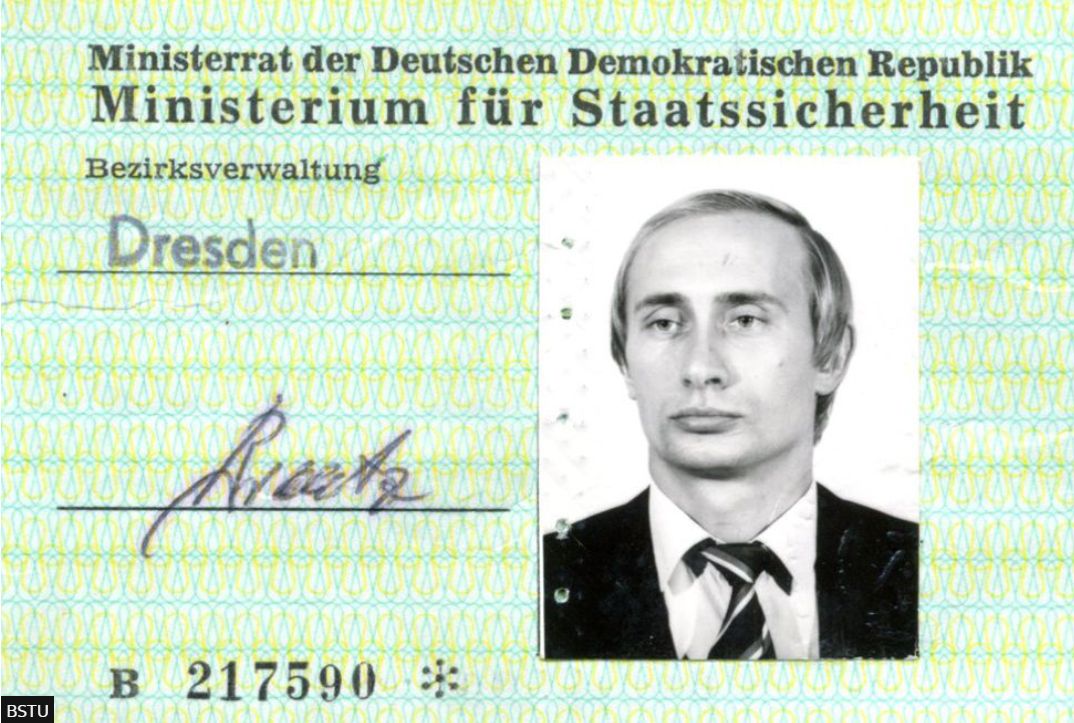

Putin had arrived in Dresden in the mid-1980s for his first foreign

posting as a KGB agent, and he was 33 when he received this Stasi ID

card:

In his biographical book Vladimir Putin, First Person. (New York: PublicAffairs, 2000), 55, Putin claims that he would

have spent another couple of years in the USSR for extra training in West

Germany, so he opted for East Germany, which did not require more training

because he wanted to leave “right away.” So the thirty-three-year-old KGB agent

set out for Dresden, which was considered a provincial backwater in the GDR,

although its party chief, Hans Modrow, was a leading reform-minded politician.

A more prestigious posting would have been in the capital, East Berlin. But

Putin relished being in East Germany, which was a consumer paradise compared to

the Soviet Union. His two-and-a-half-room apartment in a drab building on the

Angelikastrasse was a decided improvement on his childhood kommunalka, and he

was able to buy a car. Putin’s former wife, Ludmilla, later recalled that life

in the GDR was very different from life in the USSR. “The streets were clean.

They would wash their windows once a week.”

His former KGB colleague, Vladimir Usoltsev, describes Putin as

spending hours leafing through Western mail-order catalogs, to keep up with

fashions and trends.

He also enjoyed the beer - securing a special weekly supply of the

local brew, Radeberger - which left him looking rather less trim than

he does in the bare-chested sporty images issued by Russian presidential PR

today.

What else did Vladimir Putin do in Dresden during his five-year stay?

There is no agreement on this question, largely because information about his

years there is very scant. Putin’s own account of what he did is minimalist. He

says he was engaged in “the usual” textbook political intelligence activities:

“recruiting sources of information, analyzing it, and sending it to

Moscow—recruitment of sources, procurement of information, and assessment and

analysis were big parts of the job. It was very routine work.” (Putin, First

Person, 69–70.)

He was a senior case officer. In according to Fiona Hill and

Clifford G. Gaddy, Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin (Washington, DC:

Brookings Institution Press, 2014, 167) in 2001, he elaborated on his

training by saying that the key attributes of a good case officer are the ability

to work with people and with large amounts of information Putin has downplayed

the extent of his activities in the GDR. Soviet and East German senior

intelligence officials have confirmed that he was not on their radar screens,

as have Western intelligence officials. Others have suggested that Putin’s KGB

activities in the GDR may have been more extensive. Rahr claims that a “thick

fog of silence” surrounds Putin’s Dresden years, and anyway it would not be in

the interest of the German government to reveal what it knows. Some have

claimed that Putin was part of Operation Luch (“ray,” or “beam”). This was a

KGB project to steal Western technological secrets. Others argue that Luch

involved recruiting top party and Stasi officials in the GDR with the aim of

using them to replace the anti-reform die-hard Honecker regime. Indeed, Luch

became the subject of an investigation by the German authorities after Putin

came to power because they were concerned he might have recruited a network in

East Germany that survived the fall of the wall. Apparently he did begin to

recruit people, only to have them exposed after the Stasi (secret police) files

were opened following unification.

Whatever the extent of his activities in the GDR, Putin may have seen

Dresden as the first stepping-stone in an international career. But his time

there ended very differently than he had expected. On November 9, 1989, the

Berlin Wall fell, largely because, in the face of mass, peaceful street

protests, Gorbachev made a principled decision not to use force to keep in

power unpopular communist governments and because the East German police state

had run out of steam. When an angry mob showed up at the Dresden Stasi

headquarters—where the KGB was co-located in December 1989—demanding access to

its voluminous files, Putin had to defend the building and burn the documents,

“saving the lives of the people whose files were lying on my desk.” Indeed, the

furnace exploded because it could not burn all the files fast enough. In his

autobiography, Putin complains bitterly that there were no instructions from

Moscow. “Moscow was silent.… Nobody lifted a finger to protect us” from the

crowd outside. At this moment, he feared for his own safety.

One month later, a dejected Putin left Dresden. As a parting gift, his

German friends gave his family a twenty-year-old washing machine, with which

they drove back to Leningrad. The GDR would disappear nine months later, and

the USSR would follow suit two years later. Putin’s 2000 epitaph on German

unification was critical but unsentimental: “Actually, I thought the whole

thing was inevitable. To be honest, I only regretted that the Soviet Union had

lost its position in Europe, although intellectually I understood that a

position built on walls and dividers cannot last. But I wanted something

different to rise in its place. And nothing different was proposed,” he

concluded. “They just dropped everything and went away.”

Putin emerged from five years in the GDR not only with a deep

understanding of East German society but also with a foundation that would

prove important to him in his post-Soviet career. One East German who later

became an important member of his inner circle was Matthias Warnig. After the

fall of the wall, Warnig became head of the Dresdner Bank office in Saint Petersburg

in 1991, and by 2002 he ran all their operations in Russia. He subsequently

became the managing

director of Nord Stream.

The five years in Dresden influenced Putin in other ways. He lived

through the sudden collapse of a rigid, repressive system that was unable to

deal with dissent. The experience of fending off the mob at the Stasi

headquarters apparently gave him a lifelong aversion to dealing with hostile

crowds. It also reinforced for him the need for control, particularly over

opposition groups. Nothing like that should ever happen again, especially in

Russia. He left the GDR humiliated by Moscow’s unwillingness and inability to support

him during his most difficult hour, and not knowing what would await him when

he returned to the USSR, which had dramatically changed during his five years

abroad.

1. Kirk Bennett, “The Myth of Russia’s Containment,” American Interest,

December 21, 2015,

https://www.the-american-interest.com/2015/12/21/the-myth-of-russias-containment/.

2. “Interview, Mikhail Gorbachev: The Impetus for Change in the Soviet

Union,” transcript, Commanding Heights, PBS, April 23, 2001,

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/int_mikhailgorbachev.html.

3. Neil Hauer, “Putin’s Plan to Russify the Caucasus,” Foreign Affairs,

August 1, 2018,

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2018-08-01/putins-plan-russify-caucasus?cid=nlc-fa_fatoday-20180801.

4. Timothy J. Colton, Yeltsin: A Life (New York: Basic Books, 2008),

389–90.

5. Tim McDaniel, The Agony of the Russian Idea (Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, 1996), 11.

6. Edward L. Keenan, “Muscovite Political Folkways,” Russian Review 45,

no. 2 (1986): 115–81.

7. Cited in Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin, by Fiona Hill and

Clifford G. Gaddy (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), 17.

8. Angela E. Stent, “Reluctant Europeans: Three Centuries of Russian

Ambivalence Toward the West,” in Russian Foreign Policy in the Twenty-First

Century and the Shadow of the Past, ed. Robert Legvold

(New York: Columbia University Press, 2007).

9. Astolphe de Custine,

Empire of the Czar: A Journey Through Eternal Russia, translation of La Russie en 1839 (New York:

Doubleday, 1989), 619.

10.

https://collections.dartmouth.edu/teitexts/arctica/diplomatic/EA15-39-diplomatic.htm.

11. Marshall Poe, The Russian Moment in World History (Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, 2003), 82.

12. The Communist Manifesto,

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm.

For updates click hompage here