By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

From Napoleon to Lenin

As we have seen in parts one and two of

‘Islam,’ including in

the case of The Holy Empire and the Reformation,

radical changes ‘always begins with ideas that took shape on the

fringes.’ The “mainstream” has been inherently conservative throughout

time, allowing for incremental change but essentially dedicated to preserving

its power structures as the dominant ideology justifies existing relationships.

Not all radical groups are the same, and all the groups will explore take

advantage of challenges that have already shaken the social order. They ‘take

advantage of mistakes that have challenged belief in the competence of existing

institutions’ to be effective.

For a millennium, Russia has been an autocracy with

power concentrated in the hands of an all-powerful leader or leadership group.

The strong centralized rule has held together with a disparate, centripetal

empire and preserved it from the predations of powerful foreign enemies.

Sporadic attempts at democracy have ended in a return to the same default mode

of governance; the cause of the state has taken priority over the interests of

the individual.

At one point, one of the largest countries in the

world, the 1727 Treaty of Kyakhta gave

Russia privileges no other European country enjoyed, which resulted from a

conscious Qing attempt to forestall a Russo-Junghar and Buryat alliance. It worked admirably

well. Conciliated by trade, for several decades, Russia made no further

significant effort to interfere in Inner Asian politics.

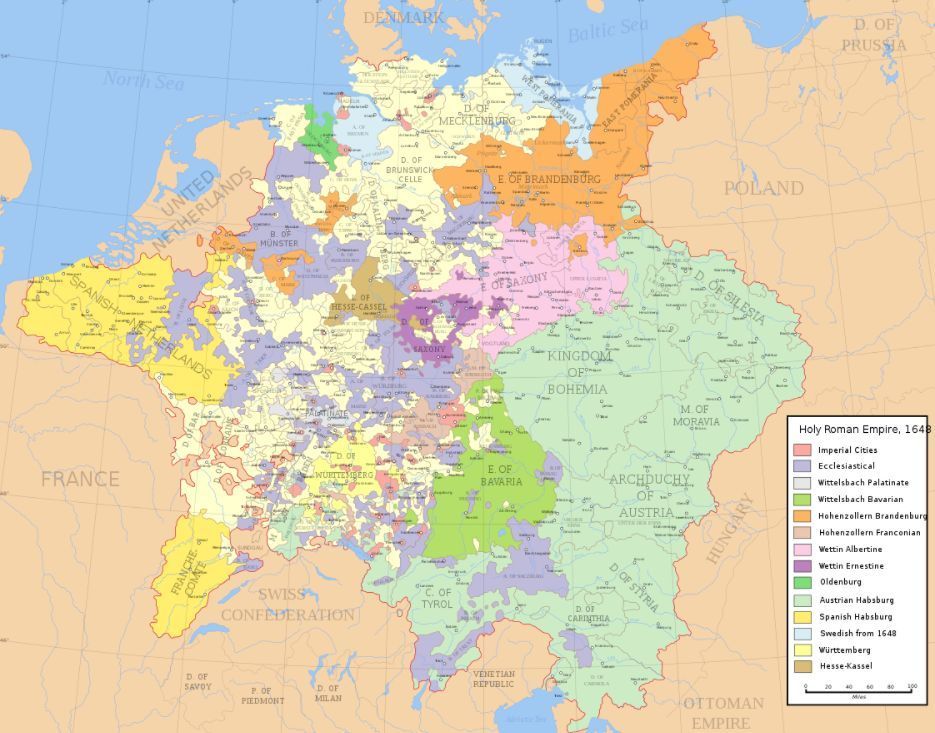

Next, Napoleon

Bonaparte, transformed Europe. He put an end to

the Holy Roman Empire, leaving the Austro-Hungarian Empire in its place;

his disruption of societies throughout Europe created revolutionary and

nationalistic movements everywhere. But his invasion of Russia was a

catastrophe. On September 14, his Grande Armée entered the ancient capital

of Moscow, only to see it too become engulfed in flames leading to his retreat

from Russia:

Within a half-century

of Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo on June 6, 1815, a new Italian nation

was in the process of formation, while the German state of Prussia was well on

its way to building a “German Empire.” France had finally rid itself of the monarchy

re-imposed after 1815, English parliaments were now elected based on

broad-based (albeit all-male) voting, and the Civil War that had torn the

United States apart on the issue of slavery was ending. Genuine participatory

democracy was now contending with hereditary monarchy on a much more even

playing field.

As we have seen in parts one and two of

‘Islam,’ radical change ‘always begins with ideas that took shape on

the fringes.’ The “mainstream” has been inherently conservative throughout

time, allowing for incremental change but essentially dedicated to preserving

its power structures as the dominant ideology justifies existing relationships.

Not all radical groups are the same, and all the groups will explore take

advantage of challenges that have already shaken the social order. They ‘take

advantage of mistakes that have challenged belief in the competence of existing

institutions’ to be effective.

Including as we will

see below, it is the particular combination of an alternative ideological system

and a period of community distress that are necessary conditions for radical

changes in direction. The historical disruptions chronicled in this book-the

rise of Christianity, the rise of Islam, Protestant

reformations, the Age of Revolution (American and French), and Bolshevism

and Nazism--will help readers understand when the preconditions exist for

radical changes in the social and political order. As Disruption demonstrates,

not all radical change follows paths that its original proponents might have

predicted.

The influence of

German idealistic romanticism on original Slavophilism, in general, has already

been mentioned inspired the Slavophiles to emphasize the organic

character of development and society. Yet the Russian idea was not a copy of German

national thought(‘Teutonophilism’) as Orthodoxy

colored it and, consequently, still represented

traditionalism.

Russia in peril

The significant

problem soon after that was Russia, where circumstances would lead to the first

and then the Second World War with the complete re-ordering of that time ‘Empires’ during the first half of the

1950s.

For a better

understanding, we suggest you start with a General overview and timeline.

In July 1914, Tsar

Nicholas II of Russia faced a dilemma, mainly of his own making.

Franz-Ferdinand, heir apparent to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire,

had been murdered by a Serbian terrorist on June 28. The Austro-Hungarian

regime was preparing to avenge itself upon the government of Serbia, which it

accused, with some justification, of having masterminded the assassination. It

was generally believed that the Austro-Hungarian army would crush the Serbian.

That would be an embarrassment to Russia, Serbia’s most prominent ally, and

alienate the Pan-Slavic public. The tsarist regime that started the First World

War was having trouble working with the modern world. The problem was not that

the system of government was autocratic, the twentieth century was going to see

a great deal of authoritarian government, the problem was that it was an

old-fashioned autocracy that depended upon the stability of relationships that

were centuries old. It didn’t help that Tsar Nicholas himself was a man of

limited intellectual attainment and that the principle for which he lived was

the preservation of the traditional regime he would pass to his heirs. He even

claimed that he had sworn to uphold the tradition of tsarist autocracy. (In

point of fact, he hadn’t sworn such an oath in so many words, but his wife,

Alexandra, liked to tell him that he had.)

Most of the

institutions upon which the tsarist autocracy had long been based were in a

state of flux as the economic conditions of Russia changed in the decades

before the war. Indeed, perhaps the only one of the state’s five fundamental

institutions functioning correctly was the interior ministry, which ran the

highly proactive secret police. The other four groups were the state

bureaucracy, the army, the landholding gentry, and the church.

The state bureaucracy

was not a significant factor by the time Nicholas II had taken the throne. It

was too small and essentially non-existent in many regions of the country. In

areas where the state bureaucracy was dysfunctional, power had devolved upon a

combination of local elective groups, zemstvo, and traditional peasant

cooperatives, which ran the villages where the property was still primarily

held in common.

The traditional

landholding gentry, primarily based on estates worked by serfs, had also fallen

on hard times. After Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War (1853–56), Tsar

Alexander II had emancipated the serfs. This was in 1861. At that point, the

gentry had already been in financial trouble, which meant it had been in no

position to resist the decree. They were somewhat mollified by “redemption

payments” from their former serfs for the land they were given upon

emancipation and the right to continue to charge for the use of “common lands”

such as forests, roads, and rivers.

The emancipation was

satisfactory to neither the peasantry nor the gentry. The peasants wished to

take over the common lands and end redemption payments. The gentry found that

they could no longer support their traditional lifestyles and moved to cities.

By 1914, less than half the gentry still possessed a rural ba.

Many gentry members

joined the developing professional classes in the cities and participated

Alexander II created zemstva (the plural of zemstvo)I

in by the time war threatened 1864. They were elected from five classes (large

landholders, small landholders, wealthy townspeople, less well-off townspeople,

andAlexander II created zemstva

(the plural of zemstvo)n and economic development; their existence had given

people a taste for non-autocratic administration. By the beginning of the

twentieth century, they functioned in all provinces of the Russian Empire other

than those in the west, where the majority non-Russian populations of

Ukrainians, Poles, Jews, and Germans were regarded as suspects by the tsarist

regime.

Of the remaining

branches of tsarist power, the agents of the Interior Ministry were widely loathed,

the army was inadequate, and the essentially medieval Church had little sway

among the educated classes. As revolution in the second half of the nineteenth

century, these educated classes were expand, these educated classes were expandinging. New industries require people with technical

skills, and the Asrovide them. Enrollment in schools

increased by 400% between 1880 and 1911, while the litera,

these educated classes were expandingcy rate for the

population as a whole increased to nearly 30% (albeit far more so in cities,

where the literacy rate was 45%, as opposed to the vastly more populous

countryside, where the rate was just over 17%).

Unfortunately for the

tsarist regime, people encountering the world of Western ideas soon became

hostile to the autocracy. Universities became hotbeds of anti-regime thought

and launching pads for various radical groups. One member of an extremist

group, a group that held that regime change could be provoked by acts of

terrorism (a peculiarly Russian belief at the time), was Aleksandr Ulyanov. He

was hanged on May 20, 1887 for his role in a failed conspiracy to assassinate

the tsar. That would cause some difficulty for his younger brother, Vladimir.

The Ulyanov boys were sons of a local school inspector, and, at the time of his

brother’s execution, Vladimir (Figure 5.4), who had excelled as a student of

classical languages, had earned a place at Kazan University. Already suspect to

the regime, he was soon expelled for subversive behavior. It was only with a

great deal of help from his mother, and many apologetic letters on his own

part, that Vladimir Ulyanov was readmitted to Kazan University a year after his

expulsion and obtained his law degree. After a few years of country living, and

continued contemplation of the works of Karl Marx and other modern thinkers

whose work he had encountered at Kazan, Ulyanov moved to St. Petersburg. Now

thinking, as result of his reading, that change in Russia would stem not from

terrorism but rather from the fulfillment of the historical process which would

lead to a proletarian revolution of Marxist theory, Ulyanov became involved

with the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, organizing workers in the

belief that they would make common cause against the “autocracy” with the

“liberal bourgeoisie.” Soon after his marriage to fellow radical Nadezhda

Krupskaya in 1897, he and she were exiled to a reasonably salubrious part of

Siberia for organizing a strike.

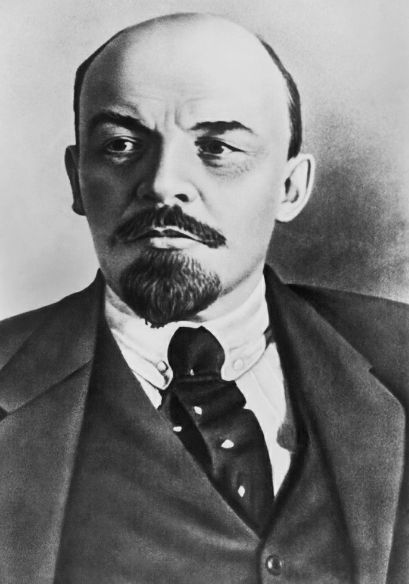

Vladimir Ilyich

Ulyanov Lenin in 1920. Vladimir Ulyanov adopted the name, Lenin, possibly

derived from the Siberian river, Lena. He is here shown with the implacable

image he favored at the height of his power.

Released in 1900, the

revolutionary couple moved abroad to continue their participation in radical

politics, joining the Liberation of Labor, a Swiss group connected with the

Russian Social Democrats. Ulyanov took up an editorial position in its Russian-language

paper Iskra (Spark). At this point his study of the Russian labor movement

convinced him that, if left to its own devices, it would fall short of forming

the revolutionary proletariat required by Marxist theory for the establishment

of a socialist society. What he saw (correctly) was that a labor movement

tended to acquiesce with capitalism if it was granted a greater share of the

profits.

Having spotted a

legitimate problem with conventional theory, Ulyanov now began gaining a

reputation as a major theorist in his own right. In 1902 he published a

pamphlet, using his new pseudonym, Lenin, entitled What is to be done. In this

work, he developed his perception about labor movements to argue the autocracy

could only be overthrown by a group of professional revolutionaries who would

inject socialism and revolutionary fervor into the workers. In his view, “the

theoretical doctrine of Social-Democracy arose quite independently of the

spontaneous growth of the working-class movement, it arose as a natural and

inevitable outcome of the development of ideas among the revolutionary

socialist intelligentsia.” It was for this reason that “class political

consciousness can be brought to the workers only from without.” The way forward

was through an organization of revolutionaries “who make revolutionary activity

their profession.” 1

Following the

publication of What is to be Done, Lenin practiced what he had preached by

seizing control of the extremist wing of the socialist movement at the Second

Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, held in 1903 in

Brussels, calling his supporters the Bolsheviks, or “majoritarians.”

The losing faction came to be known as Mensheviks or “minoritarians.” Given

that there were all of fifty delegates in attendance, this might not seem like

a particularly earth-shattering event. The fact it would become one was largely

Nicholas’ fault.

Lenin’s experience

was at the extreme end of the spectrum, but most well-educated people, who were

not recruited into government, remained contemptuous of the regime. The result

of this situation was that the state was effectively at war with what became

known as Russia’s liberal intelligentsia, as well as the radical fringe. The

increasing success of Russian industrialization, industrial productivity

increased by an astounding 129% during the 1890s, also meant there was an

expanding class of factory workers. For these people, the result of their

labors was not an improvement in their living conditions, which quite often

remained squalid. As late as 1920, 42% of homes in St. Petersburg had no

plumbing.

The collapse of the traditional regime

The collapse of the

traditional regime began in 1904/5. The emergent Empire of Japan launched a

surprise attack on Russian holdings in northern

China and Korea in 1904. The subsequent failures of the army led to rallies

in the capital of St. Petersburg, culminating, on January 9, 1905, in a mass

demonstration upon which the army opened fire, killing hundreds. As news from

the front went from bad to worse (including the destruction of the Russian

Baltic fleet, which had been sent around the world to join the fight), there

were strikes, mutinies, peasant revolts, and further mass shootings.

Various groups

emerged to put pressure on the government. Zemstva

members (organ of rural self-government in the Russian Empire and Ukraine;

established in 1864 to provide social and economic services) formed a

zemstvo congress; socialist radicals, meeting initially in Paris, formed a

Union of Liberation (Soyuz Osvobozhdeniya, first

major liberal political group founded in St. Petersburg) demanding a

constitutional monarchy, the right of self-determination for non-Russian

minorities, and the right to vote for all (male) Russians. In May, the even

more radical university students formed a Union of Unions, largely representing

white-collar workers and, like the Union of Liberation, demanded expanded

voting rights; unlike the liberals, this more radical group demanded a

parliamentary democracy and the abolition of private property.

The major difference

between the “liberal” and “radical” wings of the Russian opposition was that

the former looked to reform the tsarist government, the latter looked to

destroy it. Leaders of the liberals like Peter Miliukov

and Peter Stuve saw themselves as people who could modernize the tsarist

regime. What they would not countenance was an appeal to terrorism to bring the

regime down. On this point, they differed from the radicals, who were well

connected with Russia’s vigorous terrorist organizations. This is where Lenin’s

critique of social democratic movements is particularly important, for, in What

is to be done, he wrote:

He who does not close

his eyes cannot fail to see that the new “critical” trend in socialism is

nothing more nor less than a variety of opportunism . . . the freedom to

convert Social-Democracy into a democratic party of reform, the freedom to

introduce bourgeois ideas and bourgeois elements into Socialism.

Further, he had

written of his bitterness toward Social Democrats who disgraced the calling of

a revolutionary. This was shared by others who saw themselves as

revolutionaries in his terms, and who saw themselves as shaping the workers

into a revolutionary force. They became stronger than the Social Democrats in

the streets precisely because they developed better relationships with the

workers, whose views they saw it as their purpose to reform. So it was that

when, in October, workers in St. Petersburg organized the first elective

committee, or Soviet, to coordinate anti-government activities, one of their

leaders was a radical Menshevik named Leon Trotsky.

Faced with war in the

east and riots in the streets, Tsar Nicholas bowed to pressure from his

ministers, announcing what appeared to be a comprehensive program of political

reform. This was on October 17; the tsar’s decree included a guarantee of civil

rights for Russia’s people and the creation of a national assembly, or Duma,

which would have the power to approve the legislation.

In some quarters the

October decree garnered approval. Elsewhere it created even more chaos. In

rural Russia, peasants saw that strikes were going unpunished in the cities.

They decided they needed to get in on the action, taking what they saw as

justice into their own hands, which meant trying to force landlords to sell up

and move away. This violence, largely directed against the property because the

landlords were absent anyway, was ultimately met with extreme violence,

directed against humans, by the state.

As violence spread in

the countryside, the tsar undermined whatever goodwill (there wasn’t a lot of

it) had accrued as a result of his decision to summon the Duma. A logical

conclusion that could have been drawn from the October decree was that Nicholas

was creating a constitutional monarchy. That was not how Nicholas understood

himself. He saw the Duma as a consultative assembly to his continuingly

autocratic self.

The result of what

appeared to members of the liberal intelligentsia as the tsar’s prevarication

was that the divisions continued to fester. The first Duma, elected in 1906,

was almost immediately dissolved for being too liberal. A second Duma, also

elected in 1906, was also dissolved for excessive liberalism (it was chock full

of socialists). When a Duma that was marginally acceptable to the tsar took

office in 1907, the leading parties were conservative. These parties were

dominated by landowners with close connections to zemstva.

They believed private property rights provided the foundation for modern

civilization and were strongly nationalistic, wishing to see Russia as a

dominant power in the Middle East and the chief protector of Slavs everywhere.

They tended to be deeply suspicious of the Germans, whose assumption of racial

superiority they deeply resented. The most liberal group in the Duma (aside

from a few socialists) were people linked to urban and industrial groups. The

ministers who formed the tsar’s effective government met with the Duma, and

while there was a chair who ran the Duma’s meetings, Nicholas rather than the

Duma appointed the ministers.

The complicated

politics of the earlier Dumas had left severe splits pretty much everywhere.

Left-wing parties loathed the tsar, whom they felt had betrayed them by not

living up to the promise of a constitutional monarchy. Socialists loathed the

liberals, who, they thought, had betrayed them by dealing with the tsar. They

also tended to hate each other. In 1912, eighteen Bolsheviks, meeting in

Prague, formally split from the Social Democrats. The most important things

liberals and radicals had in common were the beliefs that workers could

overthrow the state and that the tsar was evil. Just for good measure, the

court continued to loathe the professional classes.

Beyond the walls of

the Duma, the peasants, whose hopes for massive land distribution had been

enflamed by the revolution of 1905, saw their hopes quashed by the

conservatives, and workers did not feel they had gained much of anything.

Conservatives, who regarded Russia’s Jews as potential revolutionaries, took

advantage of their power to foment mass murders of the Jewish population

(pogroms). The depth of these divisions was lost on Nicholas as he contemplated

leading Russia to war. Although Russia’s military had been modernizing at a

good clip in the wake of the catastrophe of 1904/5, it was still far from

complete functionality in the event of a major war. This was not lost on the

government, for when tensions erupted with Turkey over the appointment of a

German general to the senior post in the Turkish army, Russia had contemplated

war. At that point, Peter Durnovo, a former interior minister, had published a

memorandum in which he pointed out that: The quantity of our heavy artillery .

. . is far too inadequate, and there are few machine guns. The organization of

our fortress defenses has scarcely been started. . . . The network of strategic

railways is inadequate. The railways possess a rolling stock sufficient,

perhaps, for normal traffic, but not commensurate with the colossal demands

which will be made upon them in the event of a European war. Lastly, it should

not be forgotten that the impending war will be fought among the most civilized

and technically most advanced nations. Every previous war has invariably been

followed by something new in the realm of military technique, but the technical

backwardness of our industries does not create favorable conditions for our

adoption of the new inventions. On all points he was correct, as he was when he

predicted that the government would be blamed for disasters and that:

In the legislative

institutions a bitter campaign against the government will begin, followed by

revolutionary agitations throughout the country, with Socialist slogans,

capable of arousing and rallying the masses, beginning with the division of the

land and succeeded by a division of all valuables and property. The defeated

army, having lost its most dependable men, and carried away by the tide of

primitive peasant desire for land, will find itself too demoralized to serve as

a bulwark of law and order. The legislative institutions and the intellectual

opposition parties, lacking real authority in the eyes of the people, will be

powerless to stem the popular tide, aroused by themselves, and Russia will be

flung into hopeless anarchy, the issue of which cannot be foreseen. Durnovo

died in 1915 just as what he wrote here was proving to be completely correct.

For, even though a settlement was reached with Turkey, the salient facts he

outlined were shoved under the carpet when tensions erupted in the Balkans following

the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. Russia’s government was not alone in

behaving irrationally in the summer of 1914. The Austro-Hungarian regime was

given to magical thinking, as was the government of Serbia. But it was Russia’s

government that started the war despite the deficiencies that had been noted

earlier that year. The German government, which had encouraged the extremely

aggressive Austro-Hungarian response to the assassination, was awash in Social

Darwinist fantasies about the greatness of imperial states. This made it

possible for the chief of the German general staff to assert that it was better

to start a “preventative” war (his term for a war that would begin with the

all-out violation of the sovereignty of a peaceful state) sooner rather than

later, because Russia would complete rearming within two or three years. That

would make the “inevitable” two-front war between the Germans, the French, and

the Russians much more dangerous. Also, there was a well-developed tendency in

German thought to regard extreme violence as logical when deployed in the

interests of the state. Civilians, in the German view, were no more protected

by international conventions than were states, if “reality” dictated otherwise

in the event of war. Hence the German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann

Hollweg’s genuine surprise when England responded to the invasion of Belgium by

declaring war, and his infamous comment that he could not believe Britain would

enter the war because of a “scrap of paper” (the treaty obligating it to come

to Belgium’s defense in the event of an invasion).

The one thing all the

governments had in common, hastening into the war that would destroy them, was

the belief the war would be short. They had no plan for what would happen if an

offensive through Belgium, depending in part on the physical conditioning of

reservists (not good), should grind to a halt at the Marne; or if the

aggressive offensive into the Rhineland, lacking proper artillery support,

should be blown to smithereens. On all sides, long-standing expectations of a

future “great war” that would reshape the balance of power, linked with “all or

nothing” military planning, had created a situation in which freedom of

diplomatic maneuver was restricted. Brutal as the losses were on the western

front, the biggest disasters were those suffered by the Russians in the east.

Offensives against the pitifully equipped and worse led Austrian army in what

is now western Ukraine were successful, but two armies, sent into Germany on an

accelerated schedule per France’s request, were annihilated. The year 1915 was

even worse for the Russians. While the war in France and Belgium sputtered

along as a bloody, mud-soaked stalemate, the German army launched an all-out

offensive into Poland. Russian armies, which had not been adequately equipped,

men were routinely sent into the front lines without rifles, were pummeled.

Demoralized soldiers surrendered en masse. Around a

million Russians became prisoners of war, more than the number of soldiers

still under arms in September 1915. When the Germans ended their offensive, they

had occupied more than 10% of Russia’s prewar territory. Nicholas’ response to

the disasters of 1914 and 1915 completed the destruction of the monarchy’s

vestigial authority. In January 1915, Nicholas prorogued the Duma for seven

months. When it reconvened in July, with the army in full retreat, liberals and

conservatives joined forces in attacking the conduct of the war. A leading

figure was now a man named Alexander Kerensky; a leading topic of discussion

was the need for the Duma to take charge of affairs from the now-discredited

bureaucracy. There was no actual plan for this, but the tsar didn’t like all

the negativity. He prorogued the Duma again in August. This made the creation

of a unity government that would include himself an impossibility. Then, also

in August, Nicholas sacked his uncle, also Nicholas, the titular commander of

the army since the outbreak of the war. Nicholas assumed command, which meant

all future failures would be blamed on him, and disasters would happen even

though Mikhail Alekseev, the new chief of staff, was actually a competent

person. The previous war minister, Sukhomlinov, was

another casualty of the 1915 campaign. His replacement, a man named Polivanov,

was stunningly competent. Joining with leaders of industry he solved the

production problems that had disarmed the army in the previous two years. He

was so good at his job that Nicholas sacked him in March of 1916 (he would

later assist Leon Trotsky in creating the Red Army). Otherwise, Nicholas was

visibly under the influence of his wife Alexandra, whose loyalty was suspect

since she was German by birth; and aristocratic society was appalled by the

influence exercised through Alexandra on Nicholas by a man named Rasputin.

Rasputin had gained influence with Alexandra by claiming that he could cure the

hemophiliac crown prince (in fact all he did was hypnotize him from time to

time). Rasputin had advised Nicholas not to go to war, but now that the war was

on, he supported Alexandra in her efforts to toughen Nicholas’ resolve. The war

went better for Russia in 1916. Polivanov’s reforms meant soldiers went into

battle with weapons and the artillery had shells. The Germans were largely

distracted by their offensive against the French fortress city of Verdun and by

the British offensive on the Somme. Russian armies could thus turn on the

hapless Austrians for much of the summer, which they did. The Germans only

intervened to halt Russian progress at the summer’s end. By that time there

were new problems. Chief among them was the food supply of major cities. The

peacetime rail system was geared to shipping grain south to the Black Sea for

export. It could not be easily redesigned to ship the large quantities of food

needed by the army and urban populations largely located in the north. The

transport issue was further complicated by bureaucratic issues. The large

estates which provided most of the surplus for the market were hard hit by the

recruitment of their workers into the army; common peasants, who were less well

connected with the export market, found little reason to sell their grain when

inflation seemed to be pushing their potential returns higher. They might as

well hold on to their grain, and there wasn’t much for them to do with whatever

money they might get. With production shifted to the war effort, there were few

consumer goods on the market. Also, the production of anything was hampered by

problems in delivering coal to major cities, where there were factories to be

run and buildings to be heated. By the end of 1916, Moscow and Petrograd were

getting only a third of the food they required. The Duma, which was still

meeting in December, expressed ever-increasing frustration with the regime.

And, on the evening of December 16–17, right-wing aristocrats assassinated Rasputin.

The assassins thought they could save Russia by removing his banal influence

from the court that even they no longer trusted. It made no difference. More

serious were the morale issues afflicting the mass of the population. Peasants

recruited into the new army and sent into rear areas for training were worse

off than peasants who stayed at home with their food. Also, with much of the

professional officer corps either dead, captive, or at the front, the process

of re-professionalizing the reservists who made up the bulk of new draftees

fell into the hands of officers who were badly outnumbered even when, as some

were, they were competent. By the winter of 1916/17, Petrograd (as St.

Petersburg was now called) was filled with hungry, unhappy soldiers. There were

more than 150,000 men stationed there in barracks built for 20,000. To make

matters worse, the weather turned really foul. Such was the situation in

February 1917, when the Duma was scheduled to reconvene. Durnovo’s dire

predictions were about to be realized.

Arthur Zimmermann was

a German diplomat who liked interfering in other countries’ affairs. He is

perhaps most famous for the ludicrous telegram he sent to Mexico, urging the

Mexican government to seize the territories forming part of the southern border

of the United States. That helped precipitate the United States’ entry into the

Great War. Equally destructive was what he did with information passed upstream

by a Marxist businessman, active in Zurich, that Vladimir Lenin was living

there. Zimmermann arranged for Lenin’s return along with that of a number of

associates, including both his wife and his mistress, to Russia. On March 24

the train left Zurich for the port of Sassnitz where the travelers took ship

for Sweden and a new train that would take them through Helsinki to Petrograd.

In the evening of April 3, the train reached Petrograd’s Finland Station. Lenin

greeted the Bolsheviks and other socialists who gathered to meet him with a

speech attacking the Provisional Government.

Three weeks after

Lenin’s arrival, the Bolsheviks were organizing riots against the regime and

recruiting “Red Guards,” thugs to attack their enemies. In May, Leon Trotsky,

who had been in New York when the February revolution broke out, arrived back

in Russia. Reconciling earlier differences, Trotsky would become Lenin’s

invaluable agent, without whom the Bolshevik revolution could not have

succeeded. British intelligence had briefly detained Trotsky in Canada, then

let him continue his journey at Miliukov’s request.

That was a huge error on the part of the Provisional Government. Lenin’s plan

was to use the Petrograd Soviet as a base from which to pressure the

Provisional Government into collapse. Trotsky would be the point person for

putting the plan into action. In plotting his revolution, Lenin was aided by a

series of errors on the Provisional Government’s part (aside from not shooting

him on sight).

The Provisional

Government was an unelected entity whose members had taken over from the tsar.

Unlike members of the Central Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, who were

elected to their positions, the leadership of the Provisional Government could

not claim any sort of popular mandate. As the Provisional Government delayed

seeking a mandate, soviets were springing up all over Russia—seven hundred by

the spring of 1917, and labor unrest increased. The Provisional Government’s

first error was therefore the failure to immediately seek a popular mandate.

The Constituent Assembly was pushed off until January. The Provisional

Government’s second error, arguably as serious as the failure to seek a

mandate, was agreeing to General Order Number 1. This was issued on March 1

(13) by the governing committee of the Petrograd Soviet, addressed to the

garrison of Petrograd. Among other things, it required the election of

soldiers’ committees which would provide members for the Soviet; that the

garrison was politically subject to the Soviet; that the Soviet could

countermand orders of the Provisional Government; that off-duty soldiers should

have the same rights as civilians; and that officers, who were not to be rude

to their men, were no longer to be addressed by their titles. General Order

Number 1 undermined the discipline of the whole army and deprived the

Provisional Government of the ability to control the capital. General Order

Number 1 also made the continued prosecution of the war effort deeply

problematic. The third error was not ending the war as soon as possible.

Instead of ending the war, the Provisional Government insisted it would honor

existing agreements with the allies. It was in the context of the continuing

war that Kerensky’s tendency to dress in a military uniform and claim that he

would be the Carnot of the new regime caused concern.

The Provisional

Government rapidly lost credit. The continuation of the war, on the grounds

that it was necessary for the nation’s honor, alienated the garrison in

Petrograd, which remained the ultimate power broker. But all was not yet lost.

In June and July, the garrison was unready to abandon the Provisional

Government for the unknown quantity of the Bolsheviks. The failure of a riot,

which he inspired, to gain traction with the garrison caused

Lenin to flee to Finland.

Kerensky, proactive for

once, saw to it that “details” of massive payments from the German government

to the Bolsheviks were published in Petrograd newspapers. Lenin would not

return to Russia until October, and then it would be in disguise.

Working from his

Finnish base, Lenin instructed his followers to issue a simple message: “Bread, Peace, Land.” Kerensky, who became Russia’s

virtual dictator after the failure of the Bolshevik agitation in July, meanwhile,

alienated whatever support he might have expected from the army outside of

Petrograd. In August he suppressed a nascent coup being planned by General Lavr

Kornilov to suppress the Bolsheviks. In doing so, Kerensky alienated the

military’s leadership and was left pinning his hopes on the elections to the

Constituent Assembly, which was still not due to assembling in Petrograd until

January. A Congress of Soviets was scheduled to assemble in October.

Lenin once again

sprang into action. Taking advantage of the fact Kerensky had now alienated the

Petrograd garrison as well as the general staff and anticipating the convening

of a Congress of Soviets, Lenin ordered a coup against the Provisional Government

for the evening of October 23–24. By the morning of October 25, the Bolsheviks

had seized control of Petrograd, Kerensky had fled the scene, and the last

defense of the Provisional Government, by a battalion of female soldiers

stationed in Petrograd’s Winter Palace, ceased. The Bolsheviks, although still

a minority party, secured ratification for their seizure of power from the

Congress of Soviets. A few days later, again employing armed force, the

Bolsheviks took control of Moscow. From these two bases, they would gradually

develop the capacity to govern Russia. As important as Lenin’s leadership was

Kerensky’s failure to build any sort of coherent opposition to Bolshevik

extremism. He had no answer for the slogan “Bread, Peace, Land.” His inherent

suspicion of tsarist institutions, honed by years of antagonism between the

tsar and the Duma, made it impossible for him to build an effective coalition

with which to suppress the growing power of what had been, in February 1917,

truly the oddball fringe of the Russian political spectrum. Bolshevism was so

outside the mainstream that many of its leaders, among those who were not

incarcerated, had not lived in the country for years.

Lenin had crushed the

hollow Provisional Government. The next

challenge was building an actual government of his own. The structure that

rapidly evolved, by which a single party took over the institutions of a state,

bore an eerie similarity to states imagined in the historical past, such as the

vision Theodor Mommsen (whose History of Rome Lenin had read) had offered of

the government of Julius Caesar, who “retained the deportment of the

party-leader” while building a new Roman state after 48 BC. Even more important

for Lenin was the French experience of the 1790s. He had eighty-seven books on

French history in his library, most of them on this period; his enthusiasm for

the Jacobins had led to colleagues and rivals comparing him to Robespierre as

early as 1903. Now, with an actual coup to run, Lenin often turned his thoughts

to the events of 1793 and 1794. Despite analogies people drew, Lenin didn’t

think he was Caesar or Robespierre. But he was very aware of what happened to

them and using the Red terror he had no

intention of falling short of total success.

For updates click homepage here