By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The British Secret Services

Our research back in

the 1970s started with an article about the Political

Warfare Executive (PWE) And The Special Operations Executive (SOE') and parallel to this highlighted two

agents Codename Madeleine and a double agent Henri Déricourt

including summing all up here.

This was followed by

the harrowing story of a double agent following which the SOE in the first half of 1943 were beset by confusion and contradictory instructions. The Chiefs of Staff have dithered between

acknowledging that a severe assault on Normandy could not occur until 1944

while maintaining vain hopes that some minimal attack may be made later in 1943

if only to distract German forces from the Russian front. Winston Churchill has

continued to promote the cause of striking a bridgehead in Normandy. British

and American Chiefs of Staff have lost focus on what SOE should do to support

these muddled policies. SOE has received new orders that reduce France to a lesser

priority than Yugoslavia and Italy, emphasizing sabotage rather than providing

weapons to secret armies. Yet in the first few months of 1943, the parachuting

of weaponry to potential guerrilla forces in France increased markedly, even

while SOE officers were warned that Abwehr spies had infiltrated the critical

PROSPER circuit. These officers also know that Henri , an organizer

of landing sites in France, has been in touch with Sicherheitsdienst officers

in Paris. Lt.-General Frederick Morgan, aka COSSAC (Chief of

Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander, this Commander not yet having been

appointed), has received bizarre instructions from the Chiefs of Staff and has

started planning diversionary campaigns for Northern Europe, under the umbrella

codename of COCKADE. Francis Suttill, the leader of the PROSPER circuit,

makes two visits to Britain, the first at the end of May and a second shorter

one in early June. The guidance and instructions that he receives during these

two visits will turn out to have tragic consequences. 1.

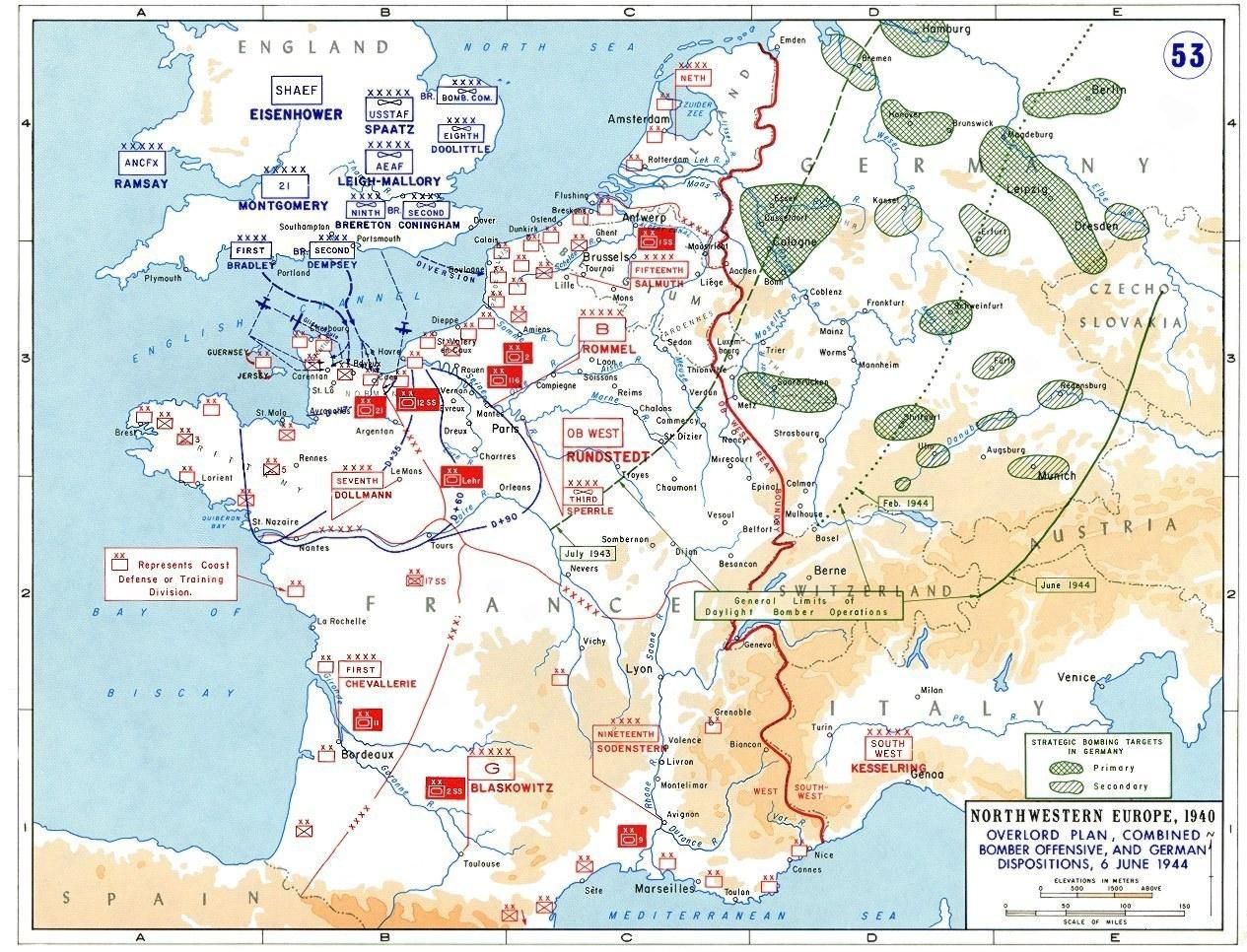

The Allied air

campaign:

We associate

Operation Overlord with the landing at Normandy, but the air campaign and

bomber offensive were a huge and essential component of its success. The blue

shows the scope of campaign to clear the way for the landing, while the red

shows Axis defensive encampments and the green shows Axis strategic targets.

You can also see the diversion out near Calais to the northeast:

Major Francis Suttill

was born in France in 1910 to an Anglo-French family, moving to Britain where

he qualified as a barrister, married and had two sons. When the Second World

War broke out, he volunteered for the Army and ending up an intelligence officer.

In 1942, he was

recruited into the nascent SOE, the hush-hush service recruited from military

and civilian ranks. In October of that year, he parachuted into France to

establish his intelligence-gathering "circuit", codenamed Physician.

Initially, he enjoyed success building up contacts and supplying local

Resistance groups.

But in June 1943,

following lapses in security, infiltration by a German double agent, and a run

of ill luck that set the Gestapo on his trail, he was captured, and eventually

executed 21 months later in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

His capture, along

with 150 agents and Resistance members connected to Physician, was a coup for

the Germans.

In the annals of

Britain's wartime espionage, there are few stories as tragic and murky as the

death of Major Francis Suttill. Codenamed Prosper, he was leader of Britain's

most important Special Operations Executive (SOE) network in France until his

capture and execution by the Nazis in 1945.

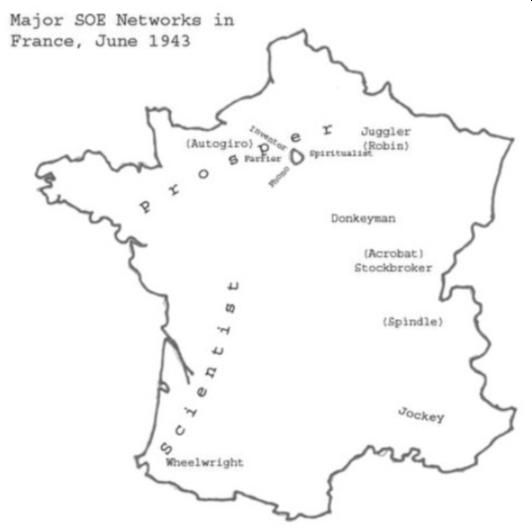

Under Suttill's

leadership the Prosper network was SOE's most important network in France,

notable for its rapid growth, wide circle of contacts and collaborators, and

the geographical reach of its operations "from the Ardennes to the

Atlantic." The fall began in April 1943 and was as fast as its rise. The

network was too large, diverse, and security too lax. The Germans penetrated

and used Prosper for their own purposes. The Air Operations officer for

Prosper, Henri Déricourt, would later be accused

of being a double agent for the Germans. Maurice Buckmaster, the leader of the

French section at SOE's London headquarters, failed to recognize clear signs

that the Germans had infiltrated.

Prosper

Major Francis Suttill,

codenamed Prosper, led a network covering Paris. He was executed six weeks

before VE day.

In what has been

called SOE's "catastrophe of 1943," Suttill was captured by the

Germans on 24 June 1943 and later executed. By the end of August 1943, the

Germans had captured many of the nearly 30 SOE agents associated with him and

hundreds of local French people working with or cooperating with SOE. Many were killed, executed,

or died in concentration camps.

As we earlier

referred to in the Harrowing Story Of A Double Agent reference, the French

operations of SOE in the first half

of 1943 were beset by confusion and contradictory instructions. The Chiefs of Staff have

dithered between acknowledging that a severe assault on Normandy could not

occur until 1944 while maintaining vain hopes that some minimal attack may be

made later in 1943 if only to distract German forces from the Russian front.

Winston Churchill has continued to promote the cause of striking a bridgehead

in Normandy. British and American Chiefs of Staff have lost focus on what SOE

should do to support these muddled policies. SOE has received new orders that

reduce France to a lesser priority than Yugoslavia and Italy, emphasizing

sabotage rather than providing weapons to secret armies. Yet in the first few

months of 1943, the parachuting of weaponry to potential guerrilla forces in

France increased markedly, even while SOE officers were warned that Abwehr

spies had infiltrated the critical PROSPER circuit. These officers also know

that Henri Déricourt, an organizer of landing

sites in France, has been in touch with Sicherheitsdienst officers

in Paris. Lt.-General Frederick Morgan, aka COSSAC (Chief of Staff

to the Supreme Allied Commander, this Commander not yet having been appointed),

has received bizarre instructions from the Chiefs of Staff and has started

planning diversionary campaigns for Northern Europe, under the umbrella

codename of COCKADE.

Francis Suttill, the leader of the PROSPER circuit, makes two visits to

Britain, the first at the end of May and a second shorter one in early June.

The guidance and instructions that he receives during these two visits will

turn out to have tragic consequences.

In this report, we

address the following research questions:

- In what manner was the proposal for COCKADE approved?

- What effect did its approval have on Suttill’s behavior and

eventual demise?

- Why were the infiltrated circuits not closed immediately after

German infiltration was detected?

- How did the decision affect SOE? Why did arms shipments to France

increase after the 1943 assault was called off?

- What did the Chiefs of Staff know about the LCS/SOE rogue deception

plan?

And the overarching

question remains: Why has the Foreign Office behaved so obstructively in

withholding information about this case?

Morgan and Operation COCKADE

The TRIDENT Conference

While discussions

between John Bevan, the Controlling Officer, and the Joint Planning Staff had

been going on for some weeks, on June 3, Lt.-General Morgan completed his draft

of Operation COCKADE, the deception scheme designed with a view ‘to pinning the

enemy in the West, and keeping alive the expectation of large-scale

cross-Channel operations in 1943’. General L. C. Hollis circulated it to the

Chiefs of Staff two days later, this group having just returned from the

TRIDENT conferences in Washington, D.C. COCKADE itself consisted of three

subsidiary operations, STARKEY, WADHAM and TINDALL, all of which were designed

to culminate in September of 1943. STARKEY is the most relevant to this story:

WADHAM was a deceptive operation designed to convince the Germans of an

American landing in Brittany in September, while TINDALL represented a

distraction in Norway. It is thus worth reproducing STARKEY’s description here:

An

amphibious feint to force the GAF [German Air Force] to engage in intensive

fighting over about 14 days by building up a threat of an imminent large-scale

landing in the PAS DE CALAIS area. The culminating date should be between

8th and 14th September.

The first startling

aspect of STARKEY was that it involved some actual assaults, not just rumors.

Morgan’s instructions had explicitly called for the German Air Force to be

brought into battle. Yet such ‘feints’ designed to engage the G.A.F.

(‘intensive fighting’) were necessarily dangerous since, if the latter

responded to the bait, lives might have been lost, and the political backlash

when the attack turned out to be half-hearted could have been disastrous.

(Morgan drew attention to such ‘undesirable repercussions’ in the last

paragraph of his submission but recommended that considerations of them not

influence the decision.) The second important dimension was the location

of the threatened large-scale landing, namely in the Pas de Calais area, away

from the coasts of Normandy where the 1944 entry would take place, but on a

heavily defended site where the German response would be expected to be robust.

Operation STARKEY

The proposal for

STARKEY is very odd. Its objective is implicitly declared to be ‘to present a

realistic picture of an imminent large-scale landing.’ Morgan’s reasoning seems

to be that the German Air Force would be brought to battle only ‘by the threat of

an imminent invasion of the Continent’ since its forces were severely depleted.

“To give our fighters the greatest advantage, the threat must be mounted

against the PAS DE CALAIS,” he added. Yet, since that area was so vigorously

defended, the operation would require heavy involvement of the Royal Navy, the

RAF, and the US 8th Air Force and would constitute a diversion from

strategic heavy bombing efforts. Why would those forces commit so readily to

something that was only a feint? If the objective had been to destroy what

remained of the GAF, accompanied by a high degree of confidence, Morgan’s plan

might have received vigorous enthusiasm from his military colleagues. Yet he

bizarrely refers merely to the chance of succeeding ‘to draw the GAF’, and that

‘14 days intensive fighting is probably the maximum we can reasonably

maintain’. Was Morgan recommending an air battle that the Allies could well

lose, or was he just casually indicating that the threat of invasion would not

be taken seriously without such a provocation?

Apart from the fact

that the feint itself was an illusion, as it did include a genuine desire to

engage the enemy, the focus on the Pas de Calais was very risky. Morgan himself

admitted that it was a very well-defended region. Would the Germans take hints

of an attack in that area seriously? It should be recalled that they had

successfully obliterated the Dieppe Raid the previous year. Yet the overall

desire ‘to keep the enemy pinned throughout the summer,’ as Morgan later

qualified the objective, thus hoping to improve the chances of the advance on

Sicily and providing help to Stalin in the East, dominated the plan. After all,

these were the express instructions the Chiefs of Staff issued on April 26.

Moreover, part of it mysteriously suggested that should the GAF be beaten and a

rapid seizure of the Pas de Calais achieved, that would signal a possible

‘complete German collapse or withdrawal.’

Yet this naïve

thinking about targets constituted a fatal flaw. The detailed text of the

COCKADE plan included some puzzling sentences concerning the choice of the Pas

de Calais. Having explained how heavily fortified the area was, and the most

strongly defended, Morgan described the level of bombardment that would be

required ‘over a limited period’ (a very unmilitary, evasive, and indefinite

bureaucratic phrase) to give the impression that a large-scale landing was

imminent. But then, amazingly, Morgan went on to write:

Port

capacities in the PAS DE CALAIS are insufficient to supply a force of more than

nine divisions, even when undamaged. We cannot, therefore, expect the GERMANS

seriously to believe that invasion of the Continent is intended if we leave our

deception plan to this area, and indeed, we shall only contain some of his

reserves if they are badly wanted elsewhere. At the same time, the paucity of

landing craft (actual or dummy) available in this country . . . . will make it

clear to him that simultaneous cross-Channel operations in more than one sector

are not feasible. We must lead him to suppose that a significant part of our

plan is a long sea voyage ship-to-shore operation partly from this country but

mainly from the USA.

Surprisingly, given

the short timetable involved, the minutes of the War Cabinet show no further

discussion of COCKADE for a while. Indeed, on June 17, Morgan moved on to the

real and authentic 1944 Operation, apologizing to the Chiefs of Staff for the delay

in submitting his initial plans for OVERLORD, and added they would be available

on July 15. The next reference to COCKADE appears in a note by General Hollis

on June 23, where he presents a response from Lieutenant General Jacob L.

Devers of the US Army, and Commanding General of ETOUSA (European Theater of

Operations, United States Army), in which Devers generally agrees with the

conclusions of the Chiefs of Staff Committee meeting of June 21 concerning

COCKADE. Then, somewhat incidentally, General Hollis brings the matter of

COCKADE to the Prime Minister’s attention on June 23, where we learn obliquely

that the War Cabinet has approved the operation. (Churchill would have been

briefed on the plan before the War Cabinet set eyes on it. The official minutes

for the meeting at which the approval was made do not appear in the official

series.) Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, is responding to

Churchill’s request for information on raids (Mountbatten’s bailiwick) after

Mountbatten refers to concurrent raids being undertaken as part of COCKADE.

Thus, the fact of the War Cabinet’s decision on COCKADE appears only as Annex 2

to Mountbatten’s note.

Yet valuable details

about the negotiations can be found elsewhere. In the War Office archives (WO

106/4223), a fuller account of some of the discussions that took place earlier

in the month appears, and some critical observations are evident. For example,

as early as April 29, Sir Alan Brooke had voiced his disagreement that the news

of the setting up of expeditionary forces ‘should be allowed to leak out

through the channels at the disposal of the Controlling Officer.’ Yet that

recommendation does not appear in the report as listed and must have been

derived from discussions. This cryptic statement presumably means that he

disapproved of a policy of using ‘double agents’ through Bevan’s TWIST

committee. However, he did not explain why he was skeptical about that channel

or offer an alternative.

Admiral of the Fleet Dudley Pound

A discussion occurred

at the Chiefs’ meeting on June 8, just after the return from Washington, when it

was resolved to discuss the plan with Morgan while the Joint Planning Staff

performed its detailed analysis and then to meet with Morgan again. Morgan

started by stating that it might be challenging to bring the GAF into battle

and that ‘to provide a sufficiently convincing display of force, battleships

for bombarding the German coast artillery had been included for use in the

later stage of the plan.’ This worried Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea

Lord, who urged ‘cautious considerations’ before the employment of battleships

in the Channel could be sanctioned. Likewise, Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the

Air Staff, could not agree to a major diversion of bombers to meet Morgan’s

requirements.

Air

Marshall Charles Portal

Later, a discussion

concerning, rather archly, ‘Control of Patriot Organisations’ followed.

The meeting recognized the importance of preventing premature risings in the

occupied countries, ‘and it was generally agreed [not unanimously?] that

all patriot organizations must be warned that there must be no general rising

without our definite instructions.’ Morgan was invited to consult with S.O.E.

on these and other topics (such as the shortage of landing craft) the Joint

Planning Staff was instructed to report.

Further doubts

surfaced the following day. A significant commentary – presented anonymously

from the War Office – appears, dated June 9. The note encourages the more

detailed analysis being performed by the Joint Planning Staff but ‘ventilates’

for the preliminary discussion of the following two critical points:

Air

Battle: One of the main advantages it hopes to attain is a profitable air

battle. Is the Chief of Staff convinced that we can be sure of obtaining this

advantage?

Political

Repercussions: We shall eventually find ourselves in a position where German

propaganda can represent that an attempted invasion has been repelled.

Premature rising by Resistance Groups on the Continent may be challenging to

avoid, and their action might be detrimental to success on a later occasion.

Having received an

individual invitation to do so, John Bevan, Controlling Officer of the London

Controlling Section, responded to Morgan’s plan, and his memorandum was

presented to the Chiefs of Staff on June 11. His opinions were strangely meek

and uncritical, but then he was, after all, the architect of the plans since

their conception had antedated Morgan’s appointment. He appeared to approve of

STARKEY and WADHAM but pointed out that the Germans were unlikely to believe

the Allies could carry off three such operations simultaneously in September.

His comments were mainly directed at TINDALL and the chances of the Germans

transferring forces hardened by cold weather to the Russian front. He completed

his report by suggesting that, after the operation had been called off, it

should be described as a ‘dress rehearsal’ rather than a feint to protect

‘secret sources,’ presumably the network of ‘double agents’ passing on

intelligence about the operation to their Abwehr controllers. In his diaries,

Alan Brooke records that Morgan came to see him on June 17 ‘to discuss various

minor difficulties he has come up against’. What they were is not said, but

Bevan presumably wanted Brooke on his side at the coming meeting.

The Chiefs of Staff

took note of Bevan’s memorandum but accepted his recommendation about

publicity. In any case, on June 21, the Joint Planning Staff (JPS) issued its

comprehensive Draft Report. In its introduction, it somewhat surprisingly

expressed confidence in the plan’s conception but rather weakly added the

opinion that it ‘should succeed in pinning German forces in the west’ and that

‘it may also provoke an air battle and will provide most valuable experience.’

It moved quickly over WADHAM and TINDALL and focused on STARKEY, where it

boldly pointed out that:

11. The

object of the plan, as stated, is to convince the enemy that a large-scale

landing in the Pas de Calais area is imminent and to bring the German Air Force

to battle,

12. There

is no intention of converting STARKEY into an actual landing if sudden German

disintegration is imminent. Entirely separate plans are being made for the

possibility of an emergency return to the Continent.

The

planning of Operation STARKEY is limited to purely deceptive measures involving

no plans for re-entry to the Continent.

These were very

significant reminders to the Chiefs of the Casablanca resolutions, and the

seriousness with which they were taken is shown by the fact that the

recommendation of ‘should therefore’ in the printed text has been amended to

‘is accordingly being’ in manuscript, reflecting that the Chiefs had endorsed

this particular observation.

The JPS also

highlighted the political repercussions, and, in consequence, a vital paragraph

soon appeared in the protocols, running as follows:

The

reactions to these operations of the inhabitants of the occupied territories

will require to be controlled by the issue in advance of the most careful

directions. The Political Warfare and Special Operations Executives have,

therefore, been instructed to prepare detailed plans setting out the measures

that should be adopted to prevent any premature rising by the patriot armies.

This is also a

significant statement. While the plan had explicitly excluded any role for

‘patriot armies’ in the STARKEY operation, the JPS implicitly ordains that SOE

agents should not encourage French resistance members to expect or support any

invasion in 1943. (Given the confirmed policy that invasion could not occur

until summer 1944, ‘premature’ presumably meant any time before then.) As far

as the build-up of arms and exhortations over the wireless was concerned, all

this well-intended foresight was too little, too late, and appears to have been

expressed in complete ignorance of what was happening on the ground. Many

‘patriot armies’ had been supplied in France and eagerly expected the invasion.

The War Office

records include the minutes of the decisive meeting on June 21. There were

several caveats: Mountbatten agreed with Pound on the battleship issue; Portal

appeared to have succumbed half-heartedly to the demand for bomber support;

Brooke raised an important point about the repercussions of bombing targets in

France and possible civilian deaths. Some awkward questions were deferred, but

the plans were essentially approved.

The argument behind

the whole COCKADE plan thus appeared to be:

1. We shall

launch an unserious attack on the Pas de Calais.

2. We want to

engage the GAF but have a slim chance of destroying it.

3. The Pas de

Calais is the best-defended area of the French coastline.

4. The area is

not large enough to support an invasion-capable force.

5. The Germans

will not take this attack seriously.

6. We plan to

supplement the air attack with bombardments by battleships (if the Royal Navy

agrees).

7. We are,

however, still determining still determining if the presence of battleships

will be helpful helpful.

8. We shall thus

pretend to launch an assault on Normandy as well, with an even flimsier feint.

9. We will add

this to the pretense of the unlikely arrival of a fleet from the USA.

10. In this way, the

Germans will be convinced that a massive assault is imminent.

It does not take the

brain of a military strategist to conclude that this was an absurd proposition.

Why on earth would the Germans be taken in by it, especially as Allied forces

were amassed in the Mediterranean in preparation for an assault on Sicily or

the Balkans? Was German intelligence so bad that the Wehrmacht would

take seriously the threat of a major assault across the Channel as well? Even

on August 7, the Chiefs of Staff discussed what reduction of German forces

would be necessary to make a 1944 cross-Channel operation possible. Moreover,

Churchill, responding to Stalin’s querulous complaint about the further

deferral of the assault, wrote to him on June 18 about the futility of wasting

vast numbers of military personnel:

It would

be no help to Russia if we threw away a hundred thousand men in a disastrous

cross-channel attack such as would, in my opinion, certainly occur if we tried

under present conditions and with forces too weak to exploit any success that

might be gained at a hefty cost.

That opinion should

have put the kibosh on exploiting ‘German disintegration.’

Moreover, the COCKADE

plan is evasive and uncomfortable about using propaganda, misinformation, and

leakage to abet the project, especially concerning SOE and MI6 networks in

France. Yet, when they considered the COCKADE plan, the Chiefs of Staff must

have known about the recent increase in arms shipments to France and the

campaigns already organized by the PWE to encourage the notion of an imminent

invasion. If that activity ceased, the Nazis would conclude that the military

movements were a sham. But if they continued, to bolster the credibility of the

feint, the Germans would take an earnest interest in infiltrating the networks

to learn more about the date and place of the opening of the ‘Second Front.’

That outcome could only be disastrous – in various ways. Therein lay the

extreme moral dilemma: deceptions can exploit ambiguity about the location of a

surprise attack but cannot dice with the actual existence or nonexistence of

such events.

And the outcome of

the assault could also have been catastrophic. What were the chances of success

of any bridgehead if substantial German forces were maintained in France

(hardly ‘pinned’, it should be stated)? The continued presence of such strength

was, after all, the objective of the Allies, and the outcome might be that a

weakly supported bridgehead would have to face a vigorous backlash and probably

be destroyed or expelled. As further evidence of muddled thinking, just a week

before, at the TRIDENT Conference in Washington, Sir Alan Brooke, in apparent

defiance of CASABLANCA resolutions, had enigmatically stated that the

‘dispersal of German forces is just what we require for a cross-channel

operation and we should do everything in our power to aggravate it’ – precisely

the opposite of what was then planned. Strategic thinking was all over the

place: it was a mess.

About this time, the

whole flimsy infrastructure fell apart. On June 24, Francis Suttill (Prosper)

was arrested in Paris, and soon afterward, he and Gilbert Norman, in a sad

effort to save lives (but not their own), encouraged their networks to reveal

where their weapons, smuggled in by SOE, were hidden.

COCKADE and the Historians

The coverage of the

early days of COCKADE by prominent historians could be better. In Volume 5 of

British Intelligence in the Second World War, Michael Howard records the

drawing up of COCKADE plans but leaves its timing (June 3) to an Endnote. He

then haphazardly goes on to describe how resources (‘double agents’ of B1A)

were enlisted to communicate aspects of COCKADE: “From the beginning of May, a

stream of messages passed through more than a dozen sources, reporting rumors,

government announcements, and regulations and observed troop movements.” That

is a clumsy and obvious anachronism: such events may well have been going on,

but they were in support of other initiatives (or put in the process by

premature anticipation of COCKADE, as I showed in my analysis of XX Committee

minutes), and not activated as a formal response to an inchoate and unapproved

COCKADE. Howard then swiftly moves on to the preparations for late summer and

reports how the Germans did not rise to the bait, the OKW failing to be deceived

about Allied intentions.

Nevertheless, he

relates how von Rundstedt, Commander-in-Chief West, anxiously watched air drops

to resistance movements in France. That was on August 31, however, when the

PROSPER network mop-up had been underway for some time. Even when STARKEY had

been called off, von Rundstedt reputedly feared a central landing as late as

November 1943. Yet,, no forces were transferred to prepare for any such

threat. The opposite occurred.

Roger Hesketh’s’ Fortitude’

In his FORTITUDE

insider history, Roger Hesketh pays scant attention to COCKADE. He dubs STARKEY

an apparent failure, as it did not succeed in engaging the German Air Force.

Moreover, he points out the fallacies in drawing the enemy’s attention to its

most sensitive spot – the Pas de Calais. He drily added: “To conduct and

publicize a large-scale exercise against an objective that one intended to

attack during the following year would hardly suggest a convincing grasp of the

principle of surprise.” In Operation Fortitude, Joshua Levine likewise

classifies COCKADE as a failure. Still, he submits that the exercise offered a

useful experience for the double-cross system and, rather weakly, gave the

planners ‘the opportunity to consider the logistics of a cross-channel

operation in advance of OVERLORD.’ On the other hand, the only mention of

COCKADE or STARKEY in M. R. D. Foot’s SOE in France is an

(unindexed) amendment he made in 2004 when he had to concede that SOE agents

were exceptionally used for purposes of deception in the promotion of STARKEY.

This is a very telling addition that Foot slipped past the Foreign Office

censors.

Anthony Cave-Brown

In his monumental

Bodyguard of Lies, Anthony Cave-Brown moved closest to the truth, although his somewhat

chaotic approach to chronology and tendency to add irrelevant detail subtract

from the clarity of his thesis. As with the other authors, he mixes pre-COCKADE

planning with the events in July and August. Using American archival sources

that came to light in 1972, however, he can show that SOE agents were used in

July and August, right through to the conclusion of STARKEY on September 9,

1943, to mislead the French patriot armies about the imminent invasion – a

probable source for Foot’s amendment. In this way, he can counter Bevan’s

wartime deputy, Sir Ronald Wingate's claim in 1969 that there was no connection

between the LCS and SOE. The tension is evident: the Foreign Office wanted to

bury the notion that SOE had acted contrary to official policy, but the facts

came out.

Moreover, Cave-Brown

lists the media exploitation that occurred, mainly in August 1943, to project

the certainty of a coming invasion. The United Press put out a bulletin that

informed the world of a move by the Allies in Italy and France ‘within the next

month,’ and even the BBC, on August 17, broadcast an ambiguous message that

Frenchmen and Frenchwomen must have interpreted to mean that they should

prepare for the imminent assault. Cave-Brown writes: “The Associated Press and

Reuters picked up this broadcast and made it world news.” All this activity by

SOE and the Political Warfare Executive (PWE) caused significant concerns for

Bevan and his team at the LCS. Such efforts defied the careful edict the Chiefs

of Staff issued about avoiding premature action by patriot forces. Matters were

out of control.

Cave-Brown also

points out that COCKADE failed because Hitler was convinced that the Allies

were bluffing and withdrew over two-thirds of his army from the West.

Between

April and December 1943, a total of twenty-seven divisions of the thirty-six in

the western command were pulled out for service in Russia, Sicily, Italy, and

the Balkans – a compliment to A-Force’s Zeppelin operations on the

Mediterranean at the expense of LCS’s Cockade operations in London.

Thus, the aims of

COCKADE were directly confounded by the clumsiness of the plan. Moreover, the

withdrawal of these German divisions could ironically have allowed the Allies

(in Cave-Brown’s opinion) to' walk ashore’ in Brittany in the summer of 1943,

virtually unopposed – a theory that demanded in-depth analysis elsewhere. For

example, Walter Scott Dunn, in Second Front Now, claimed that the

reduction in strength of the German Western Army in the autumn of 1943 could

have permitted an Allied assault to take place if the Combined Chiefs of Staff

had accepted the possibility seriously.

Yet Cave-Brown

massively mixes up the timetable when he moves to Prosper’s arrest, the

subsequent mopping up of his networks, and the confiscation of arms, making the

same mistake that others have made – that the events leading to the betrayal of

Prosper were part of the COCKADE/STARKEY deception plan. As he writes (p 338:

his sources are not identified, and the details are unreliable):

Moreover,

the SOE/PWE plan for Starkey made provision for deliberately misinforming F

section agents in the field; even before the Chiefs of Staff had approved that

plan and become fully operational in mid-July 1943, specific key F section

agents were flown to London for “invasion” briefings, and others sent to France

with instructions to carry out “pre-invasion” activities. At the proper moment, they were to be informed

that Starkey was only a rehearsal, but by then, for some of them – including

Prosper – it would be too late.

While it is true that

John Bevan, in early May, collaborated with Morgan on the first drafts of the

COCKADE plan (as I reported in April), Bevan exploited the presence of a real

(but insubstantial) attack on the Pas de Calais planned for September as an arrow

in the quiver of the rogue operation that was already underway with Prosper’s

network.

Everyone failed to

note that when Suttill arrived in London in May for his briefings, the notion

of an invasion in the summer of 1943 was still boiling in some quarters, which

excited him. But when he returned for the express meetings in early June, after

Churchill’s return, and when Morgan had just prepared his COCKADE plans,

Suttill learned how matters had changed. He was either told the truth, namely

that the new program involved a massive feint and that he was being asked to

support that activity by continuing to ready his circuits for something that

had to be described as natural, or he was deceived into thinking that an

invasion was still on the cards but had been deferred until September. It was

almost certainly the latter as if the authorities had set out to manipulate him

and his circuits; they would not want to run the risk of his undermining the

whole project. And, if they had nurtured the evil objective of having Suttill

reveal the date only under torture, extracting the truth under pressure would

have been even more convincing. What they probably told him was thus not a

total lie. In any case, he was devastated.

Prosper’s Torment

The various accounts

of Francis Suttill’s reactions

to what he was told in London are all flawed because they deal inconclusively

with the contradictions in his arrival and departure dates. (I presented then

an original theory that Suttill made two visits to the UK in late May and early

June, a hypothesis that neatly resolves all the contradictions in the various

accounts.) Thus, all the hints and attributions that appear in the works of

Foot, Fuller, Marshall, Cookridge, Suttill,

and Marnham have to be re-interpreted in

the light of Visit 1 (where Suttill is encouraged to believe that an actual

assault is imminent) and of Visit 2 (where he is made aware of the COCKADE plan

that refers to some form of attack in September and learns of the need to

restrain his forces until then).

For example,

When Cookridge writes that “Suttill had

also arranged at Baker Street for the pace of arms and explosive deliveries to

be stepped up” (not that that was in his power), it indicates clearly that the

meetings must have occurred at the end of May when Suttilthe increased

activity bolstered Suttill’s enthusiasm-hopes of an early invasion. Since

Marshall (relying very much on what Henry Sporborg told

him) imagines there was only one visit and concentrates on the post-COCKADE

briefing, he asserts that the viSuttill’s request

did not initiate the visit that he was called back to London specifically by

Churchill, even though Churchill was not in London at the end of May. “Could

the great network hold out until July?” he imagines Suttill thinking before the

invitation. Marnham, echoing Suttill Jr.,

obviously cannot explain the call from Churchill and declares that Suttill

requested the May visit himself because he was concerned about security and

needed to talk to his bosses about it.

Further, Marshall, in

turn citing Fuller, reports that Suttill informed Jean Worms (the leader of a

sub-circuit called JUGGLER) that ‘they would have to hold out until September’

(p 178); that statement confirms that the discussion must have taken after his

second visit: not only that, he gives the impression that an actual invasion

will be occurring in that month, confirming that the STARKEY plan (or a part of

it) has been explained to him. (We cannot confidently tell whether that is how

the COCKADE operation was described to Suttill or whether he decided to

misrepresent reality in the cause of the more incredible deception.) Marshall

had earlier (p 161) asserted that Suttill had been ‘knocked sideways’ by the

news that the invasion would not occur until the first week of September.

Again, it is not clear whether this was the impression given to Marshall

by Sporborg, who would have known at that time

(unlike Buckmaster) that it was untrue but may have also represented the facts

to Suttill dishonestly.

When Marnham writes (p 116) that rumors started in Sologne at the end of May that an invasion was

imminent, the author accurately echoes what Cookridge wrote

while providing an accurate date for Suttill’s first return from London. Yet, a

couple of pages later, when Marnham describes

Suttill as returning from London, with the belief that an invasion was

imminent, and on June 13 refusing to pay heed to Culioli’s requests

that parachute drops be stopped, the chronology does not allow him to point out

that this occurred after the second visit, whenSuttill was

aware that the invasion was no longer imminent. (Marnham has

recently communicated to me his agreement with my hypothesis that there were

two visits.) Suttill’s actions here suggest he was putting his whole weight

behind the rogue LCS deception plan.

On the other hand, when

Francis Suttill Jr. describes his father’s decision that the area behind the

Normandy coast was ‘one of the areas where arms were most needed to support an

invasion’ but that the drops (on June 10) took place further south because of

the presence of German troops in the area (pp 176-177), the author reflects

total ignorance of the circumstances by which arms were still being flown in

contravention of the new COCKADE policy. Earlier (p 161), Suttill had

introduced a drop near Mantes on June 16/17 where ‘some of the material was

destined for the communists . . . .; the rest was hidden for the group to use

in the expected invasion’, he l; heise is

completely tone-deaf about the political climate and machinations. He bases his

dismissal of his father’s briefing by Churchill on the fact that Churchill was

not in the UK at the end of May and ignores the evidence of a June encounter.

It is thus impossible

to determine, with complete assurance, what went through Suttill’s mind whether

he was given the complete and accurate account of the STARKEY deception plan.

He decided that he should be responsible for possible sacrifices to aid the

deception or whether he was misled into thinking that it would culminate in an

invasion in September that could be supported by resistance forces. He was,

therefore, justified in keeping his networks on the alert. What his cited

statements do confirm, however, is that he believed an invasion was imminent

when he returned at the end of May. The overwhelming evidence from the arms

build-up in the spring and he continued shipments into June and beyond after the

COCKADE plan had been approved, suggests that he was a victim of the

unsanctioned cowboy deception effort being masterminded by LCS, with the

complicity of senior SOE officers.

Yvonne Rudellat

Irrespective of both

visits, Suttill was doomed. I can add little to how the Sicherheitsdienst trapped Pierre Culioli and Yvonne Rudellat at

a checkpoint, where the Germans discovered hand-written names and addresses

being carried and crystals to be passed to wireless operators. Careless talk

and casual meetings led to the inveiglement of Suttill after Norman and Borrel

had been arrested. Readers can turn to the works of Foot, Marshall, and Marnham to learn the details. When Gilbert Norman was

shown copies of private letters that Déricourt had

carried back and forth between France and the UK, he gave up. He was

impersonated in his role as a wireless operator and brought to despair when

London rebuked him (his ghost operator) for not performing the necessary

security check to indicate that he was not transmitting under duress. He and

Suttill then made a deal with their captors that they would reveal the

locations of the arms dumps in exchange for the lives of their agents and

collaborators. The value was not honored. Scores of resistance workers, as were

Suttill, Norman, Borrel, and others, were quickly executed in 1944.

Betrayal

Henri Frager

Suttill believed

there was at least one traitor, so he sought the recall in late May. His

colleague Henri Frager, who was being manipulated by the deceptive Hugo

Bleicher of the Abwehr, had been complaining about Déricourt,

and these criticisms had resonated with Suttill, who recalled Déricourt’s overall casualness in his operations, as well

as his unjustified interest in the private lives of his contacts and

passengers. Just before he was arrested, Suttill confided these fears to

Madame Balachowsky, a distinguished biology

professor who had organized a circuit in the Versailles area with her husband.

He also told her he believed they had an agent in Baker Street.

When the initial

investigations by MI5 into Déricourt’s possible unreliability took place

in November 1943, a curious flashback to July took place. In one of the Déricourt files at the National Archives (KV 2/1131, p

16) appears an extract from notes that a Miss Torr had taken on July 9, during

a study of GILBERT (Déricourt) and ‘the PROSPER

circuit and its connections’. It runs as follows:

The

arrests in this circuit started . . . . . in April (1943) . .

. . When PROSPER went back to France at the end of May, he found the

security of his circuits further compromised by two things . . . . .

secondly, GILBERT (see below) had had a

good deal of trouble, partly through being too well known in his former

identity, partly through the indiscretions of HERVE, trained by us but sent out

by the D/F section on a special mission. GILBERT went south to lie low, and for

a while, things went well.

This is an

extraordinary entry, as much for what it does not say, what it reveals, and its

timing. The ellipses clear some embarrassing information. The arrests of April

were of the Tambour sisters by the Gestapo: Suttill foolishly tried, through an

intermediary, to pay a ransom for their release but was shockingly hoodwinked.

The first of the items excised from Torr’s report may have been the suspicions

that Pierre Culioli was indulging in Black

Market transactions, or it may have been the fact that Edward Wilkinson was

arrested on June 6. Hat subsequent German raids ‘led to the recall of Heslop a

few weeks later’ (as Francis Suttill, Jr. records). In any case, there was

enough severe concern about infiltration and betrayal to demand protective

action.

How HERVE contributed

to Déricourt’s problems is elusive. (I have

not yet been able to establish who he was. Buckmaster refers to an agent,

Hervé, in They Fought Alone.) In the file, it is reported that,

after his return to France on May 5, Déricourt found

his security endangered because his colleagues were far too careless in their

social gatherings in Paris, and his real identity was known to too many people.

The note continues:

When someone at a bar finally asked him if he had

had a good Easter in London, he felt it was time to take steps, and therefore,

he went down to Marseilles, partly to see someone we wished him to

exfiltrate and partly to lie low. Here, he came up against

the Luftflotte and, owing to

their attentions, had to go about with some of his old friends and make a show

of being friendly with the people who had put up his name to the Luftflotte.

This was a blatant

lie that Déricourt used to suggest that

these encounters were the first that he had with the German authorities.

The note then says

that Déricourt ‘returned to Paris to help

organize the June Lysander operations’ without offering dates. Suttill’s son

remarks, however, that, on the same night (June 20) that his father spoke to

Madame Balachowsky about his concerns, ‘a

Lysander operation organized by Déricourt failed

because he did not appear, nor had he collected the two passengers who were

booked to return to London, Richard Heslop and an evading RAF officer’. Using

the file HS 6/440 and quoting the testimony of Jacques Weil, Suttill Jr. states

that Déricourt had been arrested for a

short time before Prosper’s arrest and concludes:

It is

also possible that the

Germans may have warned him about something planned that night not far

from the landing grounds he was proposing to use at Pocé-sur-Cisse,

near Amboise’.

An excellent analysis

might suggest that, with these exposures well-known, the senior officers of SOE

should immediately have taken precautionary measures to inoculate against

further infiltration, such as sealing off circuits, stopping meetings and the sharing

of resources, terminating flights and shipments for a while, and ensuring the

general quiescence of all network activity until the hubbub appeared to have

subsided, and. An investigation had been completed at Baker Street. Yet, as has

been made clear, nothing of the sort occurred. When Déricourt sent

a letter to F Section at this time, explaining his contacts with the Germans at

the Luftflotte, Nicolas Bodington

(Buckmaster’s number 2) on June 21 made his infamous annotation, available

on Déricourt’s file: “We know he is in

touch with the Germans and also how and why.” Robert Marshall crucially

reported on what Harry Sporborg told him on

March 21, 1983:

There

existed a standing instruction (though SOE tended to think of it as more of an

understanding) that when it was known that one of their networks had been

penetrated, then the LCS had to be informed (usually through) ‘so that the

network in question might be exploited as quickly as possible for deception

purposes’. In this case, the

information had traveled in the opposite direction, and the LCS was

informing the SOE that the decision to exploit PROSPER had already been taken.

Neither Colonel Buckmaster nor her F Section officers were ever

informed of this decision. (All The King’s Men, p 162)

After three days of

intense interrogations of Suttill, Norman, and Borrel, on June 28, Kieffer of

the Sicherheitsdienst presented his

prisoners with photocopies of correspondence carried on flights organized

by Déricourt, identified as deriving from the

agent known as BOE/48. The manner of their betrayal became apparent to the

three.

The Dangle

From any perspective,

contact by an agent or officer of SOE with a member of one of the enemy’s

intelligence or security services should have been regarded as highly dangerous

and irregular. Thus, it is difficult to conclude that the decision to encourage

or allow Déricourt to maintain his contact

with Boemelburg was either innocent or

propelled by severe tradecraft policies. Yet the possibility that Déricourt was somehow able to mislead the Sicherheitsdienst to the advantage of SOE’s

objectives in landing agents and supplies has remained in the air. When M. R.

D. Foot wrote about the events, he referred with minimal commentary to Déricourt’s testimony of February 11, 1944, under

interrogation:

German

intelligence services did better out of intercepted reports from the field,

which they certainly saw and saw by Déricourt’s agency.

When challenged on this point, he made the evasive reply that even if he had

made correspondence available to the Gestapo, conducting his air operations

unhindered would have been worth it. (SOE in France, p 270)

This must be one of the most outrageous statements

ever made about the history of SOE, implying that, for some reason, if

the Sicherheitsdienst turned a blind

eye to the arrivals and departures taking place under their nose, they would

ignore the implications and forget about the possible threat to the Nazi

occupation of France in the form of saboteurs and secret armies. And yet, this

was presumably the mindset of Buckmaster and Bodington, who repeatedly came

to Déricourt’s defense and expressed their

regard for him and his work. With Buckmaster, it was out of ignorance and

naivety; with Bodington, duplicity and conspiracy. (The renowned and

security-conscious SOE agent Francis Cammaerts said that Bodington

‘had created a lot of death’ in France.) Even after MI5 and SOE learned,

through interrogations in early 1945, about the purloining of courier mail,

they continued stoutly defending Déricourt.

Thus one returns to

the overarching question concerning the motives and behavior (responsible for

Security), Gubbins (responsible for all of Western Europe), Dansey (Assistant

Chief of MI6), and Bevan (head of the London Controlling Section): what were they

possibly thinking by allowing Déricourt to

consort with the Nazis, and why on earth did they believe that the Sicherheitsdienst would be fooled by any ploy

that they concocted? After all, Déricourt had

been spirited out of France to Great Britain and had soon returned under the

control of a British Intelligence Service. The Nazis would be naturally very

suspicious, even brutal. If SOE/MI6 believed that, since they had employed him

when he was out of their sight, they controlled him, they were under a delusion.

Similarly, they were massively mistaken if they believed that Déricourt could act as a valuable transmitter of

disinformation to the Germans without damaging their networks' integrity. It is

tough to conclude other than their motivations concerning the safety and

security of PROSPER and other circuits were dishonorable.

The obvious question must

be: If the objective was to ‘pin’ German forces in NW France in September, why

was Déricourt not used to pass on the date

of the phony STARKEY attack by word of mouth? What was his role? He was engaged

well before the COCKADE operation was conceived and thus was deployed for more

devious ends. Déricourt was not told of the

details of STARKEY: he was a lowly air movements officer and would have been

such an obvious plant that the Germans would not have trusted what he said or

expected him to be able to gain such secrets. It would all have been too clumsy

and transparent.

On the other hand, a

whole subcurrent of suggestions (for example, from Rymills)

has flowed that Dansey had been trying to infiltrate the Sicherheitsdienst for a couple of years and

that Déricourt was his latest candidate.

Marshall is one of those observers who suggest that Déricourt was

installed in France to gain intelligence on the workings of Boemelburg’s organization, presumably to

help safeguard MI6’s agents in France. Still, such a dangerous game would have

been hardly worth the candle. In any case, given Déricourt’s background,

the Germans would have been very cautious before exposing any valuable

information to him as someone who had passed through Britain's security

apparatus.

The essence was that Déricourt had not been a Vertrauensmann, sent to Britain to infiltrate

British intelligence by convincing the British authorities of his loyalties, to

be sent on a mission to France. If SOE’s intentions were devious but benign,

the only way that Déricourt would have

survived would be by claiming he was a Nazi sympathizer, after which the Sicherheitsdienst would have made demands on

him that threatened the circuits. And that happened: he volunteered a level of

cooperation to the Gestapo, subsequently being given his BOE/48

appellation. Boemelburg must have wondered

why, if Déricourt were willing to reveal

details of SOE landings and take-offs, he would behave so indiscreetly over his

contacts with the Germans, which (as is apparent)apparent being communicated

back to London. Nevertheless, They were happy to take the evident facts and

exploit them, as the process carried no risks for them, but they would have

been suspicious of any more covert messages. As Rymills wrote,

questioning the account of Déricourt’s actions

by the Sicherheitsdienst officer

Goetz:

However

intelligent or unintelligent one believes Boemelburg might

have been, it does not ring true that he would have accepted Déricourt’s account of his visit to London under

British Intelligence auspices without demur. Anyone who confessed to the head

of an enemy’s counter-intelligence that he had been recruited and trained by

British Intelligence before being parachuted back into France as their Air

Movements Officer would most certainly have been subjected to a rigorous

interrogation in-depth for

a considerable time. He did not even spend three days in

the German equivalent of the London Holding Centre. Would anyone with one iota

of common sense believe a story about London seething with communists? Could it

possibly have been as simple as that? If it were, Déricourt was taking a gigantic risk – putting his

head in the lion’s mouth.

The nature of the

leakage was more subtle. Suttill knew the date of the invasion but would likely

reveal it only under torture – which is what happened. And, as has been

suggested by Frank Rymills, some of the letters

that Déricourt allowed the Gestapo to

photocopy may have been forged by MI6 specialists and carried revealing

messages about the circumstances of the planned invasion. Déricourt was the courier and purloiner for these

deeds: the events occurred at the same time as the famous MINCEMEAT deception

operation of early May 1943. The Germans were likelier to be taken in by

well-crafted forgeries than blatant disinformation. As Marshall writes (p 190):

From all

the interrogations and written material that had been gathered, Boemelburg was sufficiently confident to send a report

during the third week of July to Kopkow in

Berlin that stated the invasion would fall at the Pas-de-Calais during the

first week of September.

In one respect,

therefore, the ruse had been successful. The Sicherheitsdienst passed

STARKEY on the planned date to von Rundstedt and Army Group West.

SOE’s Strategy & the Chiefs of Staff

What was going

through the minds of Hambro and Gubbins if they were in control of SOE’s

destiny? Marshall (in the anecdote cited above) indicates that COCKADE was a

deception plan and that the decision had been made to exploit PROSPER was

communicated to SOE ‘about the time’ that Suttill met Churchill, namely in

early June. Yet the TWIST Committee’s conspiracies and the increase in

shipments of arms and supplies to France had been going on for months

already. Déricourt was already some ‘agent

in place,’ in contact with Boemelburg. All this

suggests that the maverick project to promote the notion that an

actual assault on the North-West French coastline was planned for 1943 –

probably because Churchill devoutly hoped it to be true when the Committee was

set up towards the end of 1942 – was very much alive and kicking and that the

notion implicit in STARKEY that the feint could conceivably be turned into a

reality allowed the TWIST activity to gain fresh wings without flying entirely

in the face of military strategy.

A more resolute

Hambro and Gubbins could have stood up to the COCKADE presentation and said:

‘Enough!’, especially as the details of the plan did not then allow for or

encourage the idea of subterranean work by SOE to further the work of the

deception. In principle, their circuits could have been protected until the

real invasion. They could have insisted that the military aspects of the plan

be pursued as specified, without any hints of assistance and preparation across

the Channel, or, better still, they could have advised that a poorly conceived

project like COCKADE should be abandoned immediately, as it would jeopardize

assets needed for OVERLORD the following year. They then should have called for

a suspension of arms shipments to France.

Yet, with the

pressure for COCKADE to be launched, the SOE leaders were hoisted with their

own petard: movements were already in place for providing weapons and

ammunition to an evolving patriot army, and if that process suddenly ground to

a halt, the illusion of an assault in September would have evaporated

completely. The Germans might not have been suspicious if there had been no predecessor

introduction of arms. So Hambro and Gubbins had to buckle under, hoping the

inevitable sacrifices would not be too costly.

The Chiefs of Staff

must have known what was going on, even though the outward manifestations of

their thinking suggest otherwise. The early minutes studiously avoid discussing

the possibility of SOEs defying the established rules to support patriot armies

in France (no longer a top-tier target country) prematurely. In his diaries,

General Sir Alan Brooke very carefully stressed that if any impulses for

invading in 1943 were still detectable, they came from his American

counterparts (Marshall and King). He earnestly repeated his assertion that such

ideas were issued from those who had not studied and imbibed the Casablanca

strategy that outlined why southern Europe had to be engaged first. Yet one

activity must have been known to the Chiefs: the increased use of aircraft to

fulfill SOE’s greater demand for drops. Given the previous fervent opposition

by Air Marshall Harris to the diversion of planes from its bombing missions

over Germany and the reliable evidence of the increase in shipments in the

spring of 1943, it is impossible to imagine that this change of policy was

somehow kept concealed from the eyes and ears of the Chiefs of Staff.

One might conclude

that, at some stage, the Chiefs concluded that the presence of substantial SOE

networks in France and their connections with armed resistance groups, instead

of being a hazard that had to be controlled, could instead become the primary

source of rumors of the invasion, a much more decisive factor than all the

dummy operations in the Channel. At the end of June (as I described above), the

PWE and SOE had been invited to suggest what actions they might take to

forestall any premature risings. This led to some very controversial exchanges.

SOE and the PWE are

on record as approving the COCKADE plan. On July 18, General Hollis introduced

to the War Cabinet Chiefs of Staff Committee a paper, dated July 8, developed

by PWE, with SOE’s ‘full consultation,’ that outlined the plans to deal with some

of the less desirable fallouts from the STARKEY Operation. The brief is given as:

- To counter the repercussions of STARKEY upon the patriot armies in

Europe,

- To counteract the effects of the enemy’s counter-propaganda

presenting the outcome of STARKEY as a failure to invade.

The report

constitutes a bizarre approach to STARKEY, as it manifestly assumes that the

effort will be entirely a feint, with no references to an engagement with the

GAF or the following-up with possible beachheads to take advantage of a German

disintegration. On the contrary, the paper reminds readers that ‘the operations

contemplated include no physical landings.’ Thus, it is a recipe for dealing

with the disappointments when STARKEY is shown to be a blank.

A quick explanation

of the political problem is set up but with very woolly terminology. The

anonymous author observes that ‘the expectation of early liberation is the main

sustaining factor in resistance’, but he does not distinguish between groups

dedicated to sabotage and the misty ‘patriot armies’ that are supposed to be

waiting in the wings. In any case, these bodies (the author states) will be in

for a major disappointment as winter approaches. The argument takes a strange

turn, presenting the fact that, since there will be no landings, there will be

no obvious cue for uprisings that would then have to be stifled, and further

states that ‘it is to our advantage that:

. . . the Occupied Peoples of the West, while prepared for the

intervention which the operations imply and for active co-operation in such

intervention, would naturally prefer that their own countries should not be

devastated by the final battles.

This is an utterly

irrelevant, illogical, and unsubstantiated hypothesis. It is unclear who ‘these

Occupied Peoples of the West’ are, but if pains must be taken not to subdue the

enthusiasm of potential ‘patriot armies,’ what were the latter expecting would

happen in the ensuing invasion? That the significant battles would all occur in

other countries and that the Nazis would fold? Then why were the French being

supplied with so much weaponry? The author is undoubtedly delusional. Yet he

says that ‘the peoples of the West’ will overcome their dismay that COCKADE was

only a diversion because they will learn that HUSKY is giving encouraging

results.

The paper then goes

on to outline what PWE and SOE should do, namely engage in a communication and

propaganda exercise to convince the patriot armies to stay their hand until

they receive the order from London to start the uprising. The report includes the

following startling paragraphs:

15. It is

suggested, however, that the P.W.E./S.O.E. has a positive contribution

to the success of COCKADE itself.

16. The object would be:

To assist

the deception by producing the symptoms of underground activity before D-day, which the enemy

would naturally look for as one preliminary of an actual invasion.

It goes on to give examples

of operations ‘on a scale sufficient to disturb the enemy, but would be so

devised so not to provoke premature uprisings or to squander any stratagems or

devices needed in connection with a real invasion ’such as printed instructions

on how to use small arms, and broadcasts by ‘Western European Radio Services’

on how the civilian population could make itself into ‘useful auxiliaries’.

This seems to me

utterly cynical. During a period immediately after the arrests of Suttill,

Norman, and Borrell and the betrayal of arms and ammunition dumps, when news of

the crackdown by the Gestapo was being sent to London by multiple wireless

operators (including over Norman’s hijacked transmitter), the PWE and SOE

contrived to recommend the creation of ‘the symptoms of underground activity

coolly’. This suggestion was made when SOE and MI5 carefully inquired into the

penetrations and arrests. [N.B. The news was not confined to SOE.]

Either the spokesperson was utterly ignorant of what was going on (highly

unlikely), or he was wilfully using STARKEY

as an opportunity to provide an alibi for the collapse of the networks.

Furthermore, for the

seven days leading up to D-day (the September 1943 date for STARKEY), the units

suggested that leaflets should be dropped addressed to ‘the patriots,’ telling

them that the forthcoming activity was only a rehearsal. Astonishingly, the

author suggests that the B.B.C. should be brought in ‘as an unconscious agent

of deception’, encouraging the notion that a coming assault was actual until

the broadcasting service, like the press, would be informed that the operations

were only a rehearsal. This initiative was a gross departure from policy since

the B.B.C. had carefully protected a reputation for not indulging in black

propaganda and instead acted as a reliable source for news of the realities of

war throughout Europe.

A final plea (before

outlining a brief plan as to how the PWE and SOE should play a role in this

deception) is made for a concerted effort to enforce the idea that patriot

armies should be subject to the control of the Allied High Command. Still, it

is worded in such an unspecific and flowery way that it should have been sent

back for re-drafting:

From now on,

we should even more systematically build up the concept of the

peoples of Occupied Europe forming a series of armies subject to the strictest

discipline derived from the Allied High Command in London.

Build a ‘concept’? To

what avail? How would ‘peoples’ form a ‘series of armies’? How would discipline

be enforced – for example, with the Communist groups or de Gaulle’s loyalists?

The paper seeks to maintain that only through the communications of the Prime

Minister and others to the ‘contact points’ established within Western Europe,

and ‘upon the evidence of the genuineness of our D-day instructions, will

depend the favorable or unfavorable reaction to COCKADE.’

Suppose the Chiefs of

Staff had spent any serious time reviewing this nonsense. In that case, they

should have immediately canceled the COCKADE operation, as its rationale and

objectives were nullified by the probable embarrassing fallout. In any event, their

concerns should have been heightened by an ancillary move that occurred soon

afterward. As Robert Marshall reported, on July 26, Stewart Menzies, the head

of MI6, sent a note to the Chiefs of Staff via Sir Charles Portal that claimed

that SOE in France was essentially out of control and that SOE should be

brought under MI6’s management. Of course, this was also an utterly cynical

move since Dansey had been responsible for infiltrating Déricourt into the SOE organization. But Gubbins could

hardly accuse the vice-chief of MI6 of being ultimately accountable since he

would then have to admit how woefully negligent he had exercised proper

security procedures in his units.

Instead, Gubbins read

the note, was highly embarrassed, and tried to counter that the groups under

his control ‘had not been penetrated by the enemy to any serious extent,’

instead naively implying that they had, of course, been penetrated and that he

was confident that the degree of such was minor. He shamelessly tried to

conceal the full extent of the damage from his masters but failed to make his

case. On August 1, the Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee recorded their

opinion that SOE had been ‘less than frank in their reports about their

situation in France.’

SOE was in trouble.

Yet STARKEY was not canceled, and the propaganda campaign continued. Gubbins

plowed on, recommending increasing aid to the French field to the maximum and

noting that ‘the suffering of heavy casualties is inevitable.’ And then Hambro,

Gubbins’ boss, had to respond to a negative opposingandum from

Portal about diverting bombers to support SOE’s operations. In a long letter to

the Chiefs of Staff dated July 26, Hambro cooked his goose since he showed that

he was unfamiliar with official strategy and was also not in control of the

(largely phantom) armies whose strength he had exaggerated. He made a plea for

more air support, claiming that maintenance of the effort was essential if SOE

were to fulfill its mission. He added, however, two damning paragraphs

highlighting relevant factors, which merit being quoted in full:

- As may be expected, the recent increase in our operations

has increased enemy activities to counter them and a consequent higher

wastage rate among our men in the field. Therefore, maintaining our

organizations at their present strength and day-to-day activity requires

increasing our current efforts.

- People on the Continent were confident that the Allies would invade in

1943. The recent developments in ITALY will confirm this feeling.

Daily reports from the field reiterate that people of occupied

countries relied upon the Allies returning to the Continent in

the Autumn of 1943.

Suppose the

Allies do not return to North-west Europe. In that case, there will

be a severe fall in morale and, consequently, in the strength

of the Resistance movements, which depend significantly on their vigor and

confidence that gives the will to resist. The only way of

countering the deterioration will be by showing the people of occupied

countries that the Allies have not failed them. This cannot be done by

propaganda and broadcast alone but requires to be backed up by a steady flow

of significantly increased deliveries of arms and other

essentials.

The propaganda

campaign behind COCKADE did not help Hambro, but he showed an alarmingly naïve

understanding of the military climate and the realities of SOE operations. His

statements about the possibility of a widespread return to the Continent in

1943 were absurd and irresponsible, given the Casablanca decisions and what the

resistance in (for example) Norway was being told. He simplistically grouped

many disparate nations and their populations (‘People on the Continent’) as if

generalizations about their predicament, hopes, and expectations could sensibly

be made. Every country was different – a truth with which Hambro was not

familiar. He proved that his organization could not control the aspirations and

activities of the groups who were, in fact, dependent upon SOE, and he showed

that the tail was wagging the dog. He tried to finesse the matter of ‘wastage

rates’ in his field agents without admitting the gross penetration by the

Germans that had occurred. He tried to preach to the Chiefs of Staff that they

should endorse policies they had already rejected. Unsurprisingly, he lost his

job a month or so later.

The Aftermath and Conclusions

This chapter

essentially closes with the arrest of Francis Suttill (Prosper). Yet, there is

much more to the story. In late July, Bodington paid a surprise visit to Paris

to investigate what had happened to Prosper’s network. It was an

extraordinarily rash and stupid decision: he was watched by the Sicherheitsdienst but was allowed to return

home unmolested. The assault aspect of COCKADE turned out to be an abject

failure, as the Wehrmacht ignored any rumors or feints to

engage the GAF. (Brooke does not mention it in his diaries.) Even the continued

activity of SOE in France, designed to keep many Wehrmacht divisions

‘pinned,’ did not prevent the release of troops to the Balkan and Russian

Fronts. Arms drop to French resistance workers continued. The Nazis seized more

arms caches and arrested and executed more agents and resistance workers. Déricourt came under fresh suspicion in the autumn of

1943 and was eventually ordered back to the UK and interrogated at great

length. After the war, he was put on trial by a military court in Paris, but

Bodington exonerated him. Having been rebuked, SOE came under the control of

the army men late in 1943. OVERLORD was, of course, successful in June 1944 and

was abetted in some notable incidents by patriot armies.

I recommend readers

turn to Marnham, especially for the dénouement of Déricourt’s story. Chapter 20 of War in the

Shadows, ‘Colonel Dansey’s Private War,’ gives an excellent account of the

self-delusion and distortion that surrounds the case of his treachery. Yet that

may not be enough. Again, I believe Marnham’s account

is flawed because of some critical misunderstandings or oversights. Déricourt was not a Sicherheitsdienst

officer who was ‘turned’ at the Royal Patriotic School in Wandsworth; he was an

amoral individual who ingratiated himself with the Nazis by criticizing

‘communist-ridden’ London.

The shipments of

weaponry in the spring of 1943 were not in early anticipation of the COCKADE

plan but the result of a rogue LCS operation that had been going on for months.

COCKADE was essentially the child of Bevan, who passed it on to Morgan. Francis

Suttill crucially made two visits back to the UK in late May

and early June, which has enormous implications for the ensuing events. The SOE

tried to deceive the Chiefs of Staff over the penetration of its circuits.

These ‘lapses’ do not undermine the strong case that Marnham makes

about the tragic manipulation by SOE & MI6 of the doomed French courses,

but it does mean his story is inadequate. And there may be more to be

unraveled. At some stage, I may want to return to the enormous archival

material comprising the files on Déricourt, Hugo

Bleicher, and other German intelligence officers. Yet it will be exhausting and

challenging to reconcile the testimonies of so many liars and deceivers.

I believe there is a

severe need for a fresh, authoritative, and integrative assessment of SOE’s

role in the events of 1943 and 1944. Olivier Wieviorka’s 2019

work The Resistance in Western Europe, 1940-45, is a valiant

contribution. Still, he skates over the complexities a little too quickly, with

the result that he comes out with summarizations such as: “The statistics

confirm that, before 1944, the British authorities did not believe it useful to

arm the internal resistance”, an assertion that is both frustratingly vague but

also easily contradicted. (Some of the less convincing conclusions may be

attributable to an unpolished translation.)

Halik Kochanski’s

epic new work Resistance: The Underground War Against Hitler, 1939-1945,

covers a vast expanse of territory in an integrative approach to international

resistance, but it, therefore, cannot do justice to every individual situation.

Some of her chapters are synthesis masterpieces, but many of her stories are

re-treads of familiar material. Moreover, she relies almost exclusively on

secondary sources and treats all as equally reliable. Kochanski nevertheless

offers a very competent synopsis of the downfall of the Prosper circuit and the

ripple effect it had on other networks. She mentions Déricourt’s

treachery but does not analyze it in depth, drawing attention to the

contradictions in Buckmaster’s two books. She classifies All the King’s

Men as a‘ conspiracy theory’ and praises unduly Francis Suttill’s Shadows

in the Fog as if it were the last word on the subject. She does not

appear to have read War in the Shadows, and her account lacks any