By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Compilation of the Historical Overview

in Chuck Schumer's New book

As described by Schumer, the roots of Zionism can

be traced back to ancient Jewish history and religious traditions, where the

concept of "Zion" symbolized both a physical place and a spiritual

aspiration. Zion, a biblical term for Jerusalem and the Land of Israel, held

deep significance in Jewish prayers and rituals. For centuries, the Jewish

people, dispersed across various continents after the destruction of the

Second Temple in 70 CE, maintained a connection to the land of Israel

through religious customs, writings, and prayers. The longing for a return to

Zion was enshrined in liturgy, with Jews concluding the Passover Seder each

year with the hopeful declaration, "Next year in Jerusalem."

However, this

religious and cultural longing did not transform into a political movement

until the late 19th century, when Jewish communities across Europe began to

confront increasing social, political, and economic pressures. The rise of

nationalism in Europe, coupled with a growing wave of anti-Semitism,

particularly in Eastern Europe, made many Jews realize that integration and

assimilation were becoming increasingly difficult, if not impossible. The

pogroms of the late 19th century in Russia, where Jewish communities were

violently attacked and persecuted, added urgency to the need for a solution to

what was commonly referred to as the "Jewish Question."

Zionism, as a

political movement, was born out of this sense of desperation and the belief

that Jews could only secure their survival through self-determination in their

land. While various thinkers and rabbis had advocated for Jewish resettlement

in Palestine before this time, it was in the late 19th century that the idea

gained traction among Jewish intellectuals and activists, particularly under

the leadership of figures like Theodor Herzl, who gave the movement a coherent

political framework.

Key Figures: Theodor Herzl and Others

As earlier described by us, Theodor Herzl is often regarded

as the father of modern political Zionism. Born in I860 in Budapest, Hungary,

Herzl was a well-educated journalist and playwright who initially believed that

Jews could integrate into European society. However, Herzl's views changed

dramatically after he covered the Dreyfus Affair in France, a scandal in which

a Jewish French army officer, Alfred Dreyfus, was wrongly accused of treason.

The wave of antisemitism that accompanied the affair, even in a country as

politically liberal as France, convinced Herzl that Jews could never fully

assimilate into European societies.

In response to this

realization, Herzl penned his influential work, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), published in 1896.

In this book, Herzl argued that the Jewish people were a nation entitled

to a state of their own and that the most logical location for this

state was in Palestine, the ancient homeland of the Jewish people.

HerzI's vision was pragmatic, emphasizing the need for

political and diplomatic efforts to secure international support for

the establishment of a Jewish state. He called for organized Jewish

migration to Palestine and the creation of Jewish

institutions capable of governing a future state. Herzl's ideas resonated

with many Jews across Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe, where Jewish

communities faced widespread persecution. In 1897, Herzl convened the First

Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, an event that is widely considered the

formal birth of the Zionist movement. The Congress brought together Jewish

leaders and activists from around the world to discuss the practical steps

needed to achieve the goal of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. At the Congress,

the delegates adopted the Basel Program, which declared that "Zionism

seeks to establish a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under

public law."

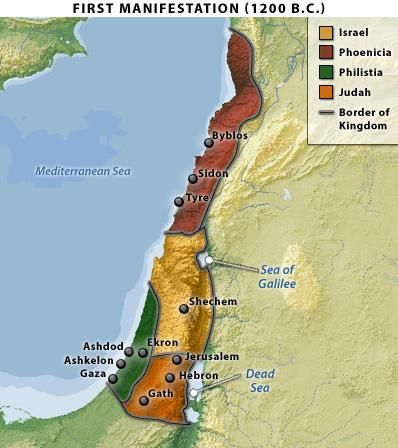

From a historical

point of view one could say, that 'Israel' has manifested itself three

times in history. The first manifestation began with the invasion led by Joshua

and lasted through its division into two kingdoms, the Babylonian conquest of

the Kingdom of Judah and the deportation to Babylon early in the sixth century

B.C. The second manifestation began when Israel was recreated in 540 B.C.

by the Persians, who had defeated the Babylonians. The nature of this second

manifestation changed in the fourth century B.C., when Greece overran the

Persian Empire and Israel, and again in the first century B.C., when the Romans

conquered the region.

The second

manifestation saw Israel as a small actor within the framework of larger

imperial powers, a situation that lasted until the destruction of the Jewish

vassal state by the Romans.

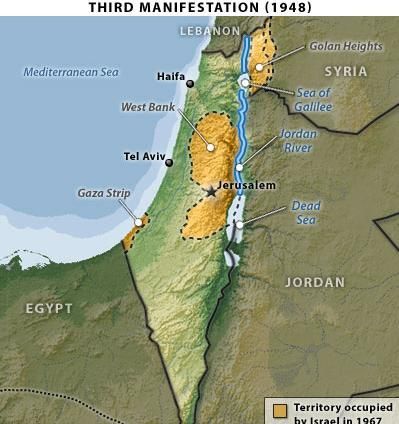

Israel’s third

manifestation began in 1948, following (as in the other cases) an ingathering

of at least some of the Jews who had been dispersed after conquests. Israel’s

founding takes place in the context of the decline and fall of the British

Empire and must, at least in part, be understood as part of British imperial

history.

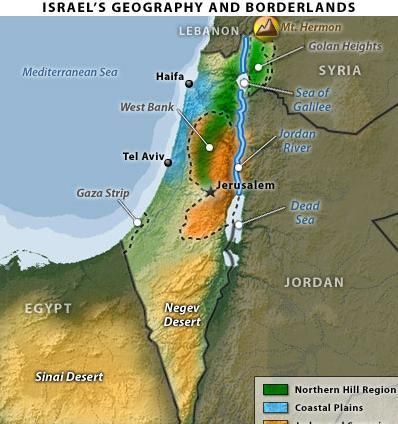

Israel’s reality

today is this. It is a small country, yet must manage threats arising far

outside of its region. It can survive only if it maneuvers with great powers

commanding enormously greater resources. Israel cannot match the resources and,

therefore, it must be constantly clever. There are periods when it is

relatively safe because of great power alignments, but its normal condition is

one of global unease.

On the other hand the

Arabs don’t really care about the Palestinians other than for the destruction

of Israel. For example Gaza is a nightmare into which Palestinians (fleeing

Israel) were forced by the Egyptians.

The idea for

what where de facto Arab-Muslims to call themselves 'Palestinians'

came as a reaction to the Jewish migration to what is now Israel

after WWI. When World War I ended the rule of the Ottoman Empire, which

controlled the Middle East came to an end.

Shortly after the

British took over in 1920 they moved the Hashemites to an area in the northern

part of the peninsula, on the eastern bank of the Jordan River. Centered around

the town of Amman, they named this protectorate carved from Syria “Trans-Jordan,”

as in “the other side of the Jordan River,” since it lacked any other obvious

identity. After the British withdrew in 1948, Trans-Jordan became contemporary

Jordan. The Hashemites also had been given another kingdom, Iraq, in 1921,

which they lost to a coup by Nasserist military officers in 1958.

West of the Jordan

River and south of Mount Hermon was a region that had been an administrative

district of Syria under the Ottomans. It had been called “Philistia” for the

most part, undoubtedly after the Philistines whose Goliath had fought David

thousands of years before. Names here have history. The term Filistine eventually came to be known as Palestine, a

name derived from ancient Greek — and that is what the British named the

region.

As earlier described

by us here, Cultural

Zionism, initially, Hebrew and Jewish culture such as language, arts

identity, and religion, however, had been important rather than the potential

establishment of a state. They, in effect, saw Zionism as a solution to the

problems of Judaism, and they were associated with the thinking of the writer

Asher Ginsberg (1856-1927). The second grouping, the political Zionists, argued

that the need for territory was the most important requirement of the Zionist

movement. Indeed, Herzl's pragmatic reaction to the proposals for the Ugandan

option was a clear illustration of the aim of the political Zionists. As the

Zionist movement as a whole grew, so more and more people started to emigrate

to Palestine. These new immigrants expanded existing Jewish colonies and

founded new ones. In 1909, the first Kibbutz was started by the Sea of Galilee,

called `Kibbutz Degania', and in the same year Tel Aviv was founded along the

shoreline from Jaffa.

Perhaps the greatest

myth surrounding the arrival of the various waves of Jewish immigration to

Palestine during this time (Aliyah) was the question of their motives for

coming in the first place. The majority of the immigrants who came to Palestine

did not do so for Zionist reasons. Rather, they came for a variety of reasons

that involved both persecution in their country of origin and a lack of third

country option. The latter became an increasingly important factor when the

United States closed its doors to Jewish immigration at the end of the 19th

century.

Many who came to

Palestine found life there to be too harsh and left. Emigration has been a

constant problem for the Zionist movement, both in Palestine and subsequently

in Israel. In both the Yishuv and the subsequent state of Israel, there is

clear linkage between immigration and security. In short, as much of the land

as possible had to be settled in order to control it.

In the early days of

the first and second Aliyahs, the immigrants,

most of whom came from Eastern European urban backgrounds, struggled with

having to make the land fertile. It is here that one of the great dilemmas of

the Zionist movement became apparent. Who should farm the land? The first immigrants

took the view that local Arab labor was both better equipped to undertake this

arduous task and also very cheap. The second wave of immigrants took the view

that the state for the Jews would be built using Hebrew labor, and they clashed

with the veteran immigrants over this question. Eventually, the second group

carried the day, but the debate about using Arab or foreign labor never really

went away.

In Eastern Europe,

Zionism remained a rather small movement, particularly when compared

with socialist Yiddishist groupings

like the Allgemeiner Yiddisher Arbeiterbund-the "Bund"-which had been founded in

1897, the same year as the World Zionist Organization. Zionists also found

themselves in competition with Jewish activists drawn to a non-sectarian

Marxism.

However the

settlement activities in Palestine represented the practical approach to

Zionism, and this combined with political Zionism to form what was termed

`synthetic Zionism', which became closely associated with Chaim Weizman

(1874-1952). Born in Russia, Weizman played a central role in the development

of the Zionist movement and was to become Israel's first president. In 1904,

Weizman emigrated from Russia to Britain, where he lobbied for the Zionist

cause and played an influential role in winning some degree of British

recognition for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Along with David Ben-Gurion,

Weizman became one of the central figures of the pre-state Zionist movement,

serving as President of the World Zionist Organization during 1921-31

and 1935-46.

The cultural Zionists

succeeded in defining the goals which the Labor Zionist parties would

eventually implement. The first trend in Zionism, political Zionism, appealed

mainly to Western European intellectuals and contributed little in the way of

an ideology to the people who built up the Yishuv. Political Zionist prejudices

were absorbed into Zionist myth as the Yishuv moved inexorably toward

self-determination during the 1930’s. Only after they were thought-rightly or

wrongly-to anticipate the bitter lessons of World War II did they put cultural

Zionism in eclipse.

While Herzl was the

most prominent leader of the early Zionist movement, other key figures

contributed to the development of different strands of Zionism. For example,

Ahad Ha'am (Asher Ginsberg)

was a leading proponent of cultural Zionism, which emphasized the revival of

Jewish culture and spirituality in Palestine rather than the establishment of a

political state. Ahad Ha'am was concerned that political Zionism, as envisioned

by Herzl, could lead to conflict with the Arab population in Palestine and

argued that the focus should instead be on creating a cultural and spiritual

center for the Jewish people.

Labor Zionism,

another important branch of the movement, was led by figures like David

Ben-Gurion and Berl Katznelson. Labor Zionists believed that the future Jewish

state should be built on principles of socialism and collective labor.

They envisioned a society based on agricultural communes, known as kibbutzim,

where Jewish workers would rebuild the land through their own labor. Labor

Zionism would later become the dominant force in the Zionist movement and in

the early years of the State of Israel, as many of its leaders, including

Ben-Gurion, went on to hold key positions in the Israeli government.

Together, these

various streams of Zionism, political, cultural, and labor, contributed

to the diversity of thought and approaches within the movement, each

playing a role in shaping the future Jewish state.

The First Aliyah and Early Jewish Settlements

The practical

realization of Zionism began with the waves of Jewish immigration to Palestine,

known as Aliyah (literally meaning "ascent"). The First Aliyah took

place between 1882 and 1903, during which time approximately 25,000-35,000

Jews, primarily from Eastern Europe, immigrated to Palestine. These early

settlers were motivated by a combination of Zionist ideals and the desperate

conditions they faced in their home countries, particularly in the Russian

Empire, where Jews were subjected to pogroms, discrimination, and economic

hardship.

The First Aliyah

settlers faced numerous challenges upon arriving in Palestine. The land was

under Ottoman rule at the time, and the Jewish immigrants had to navigate

complex legal and political systems to acquire land and establish communities.

Much of the land they purchased was difficult to cultivate, often consisting of

swamps and arid regions. Malaria, poverty, and hostile relations with local

Arab communities further compounded the difficulties faced by the early

settlers.

Despite these

challenges, the First Aliyah was significant in laying the groundwork for

future Jewish immigration and settlement. Many of the new arrivals

established agricultural communities, some of which, were funded and

supported by wealthy Jewish philanthropists, such as Baron Edmond de

Rothschild. Rothschild played a crucial role in financing agricultural

settlements, providing the financial backing needed to make these communities

viable. The early settlements established during the First Aliyah included

Petah Tikva, Rishon LeZion, and Zikhron Ya’akov, many of which remain prominent

cities in Israel today.

The settlers of the

First Aliyah were motivated by a sense of pioneering zeal, viewing their

efforts as part of the Zionist dream to reclaim and rebuild the Jewish

homeland. The idea of working the land and establishing self-sufficient

communities was central to the Zionist ethos, particularly among Labor

Zionists, who saw manual labor as a means of creating a new Jewish identity

based on independence and self-reliance.

The First Aliyah also

marked the beginning of tensions between the Jewish settlers and the Arab

population of Palestine. While relations between Jews and Arabs had been

relatively peaceful under Ottoman rule, the arrival of increasing numbers of

Jewish immigrants seeking to establish permanent settlements on land that had

traditionally been worked by Arab peasants led to growing friction. Arab

leaders and landowners began to view Zionism as a threat to their economic and

political interests, particularly as more land was purchased by Jewish

settlers, often displacing Arab tenants in the process.

The early years of

Zionist settlement in Palestine were, therefore, characterized by both

achievements and challenges. On the one hand, the First Aliyah laid the

foundation for future Jewish immigration and settlement, establishing the first

Zionist agricultural communities in Palestine. On the other hand, it also sowed

the seeds of the conflict between Jews and Arabs that would continue to

escalate.

After the First

Aliyah, subsequent waves of Jewish immigration followed, each contributing to

the growing Jewish presence in Palestine, The Second Aliyah (19041914) brought

more settlers, many of whom were inspired by socialist ideals and sought to

build a new, egalitarian Jewish society through communal fanning and labor.

These immigrants were instrumental in establishing the kibbutz movement, which

would become a central feature of the Zionist project.

As Jewish immigration

continued throughout the early 20th century, the Zionist movement gained

momentum, building the institutions, infrastructure, and settlements that would

eventually pave the way for the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. However,

this period also witnessed the deepening of Arab resistance to Zionism, setting

the stage for the long and complex conflict that would follow.

The Balfour Declaration and its Impact

The Balfour

Declaration of 1917 represents a pivotal moment in the history of Zionism and

the Middle East. Issued by the British government, the declaration articulated

support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people”

in Palestine. This seemingly straightforward statement would have profound

implications for the Jewish people, the Arab population of Palestine, and the

geopolitical landscape of the region. This chapter examines the context

surrounding the Balfour Declaration, the promises made by Britain to the Jewish

people, the international reactions it provoked, and its long-term geopolitical

significance.

British Promises to the Jewish People

The origins of the Balfour Declaration

can be traced back to World War I, during which Britain sought to

secure support from various groups to bolster its military efforts. The war,

which began in 1914, saw the British Empire engaged in a brutal struggle

against the Central Powers, notably Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman

Empire. As the war progressed, Britain faced significant challenges, including

a critical need for additional manpower and financial support.

In this context,

British officials began to recognize the potential value of garnering support

from the Jewish community, particularly in the United States and Russia, Jewish

leaders had long advocated for increased immigration to Palestine and the establishment

of a Jewish homeland- They argued that a formal declaration of British support

would galvanize Jewish opinion in favor of the Allied war effort and encourage

Jewish communities to lobby their governments for additional support.

In 1916, the British

government initiated secret negotiations with key Zionist leaders, including

Chaim Weizmann, a prominent chemist and Zionist activist. Weizmann and others

emphasized the strategic importance of a Jewish state in Palestine as a means to

promote stability in the region after the war and to create a strong ally for

Britain in the Middle East.

To understand the

complexity of Israel's founding, we must first delve into the region's rich and

layered history before the 20th century. The ancient kingdom of Israel, founded

around the 11th century BCE, became the first organized Jewish state, while its

southern neighbor, the Kingdom of Judah, would later become the nucleus of

Jewish religious and cultural identity These kingdoms fell to successive

empires—the Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, and finally the Romans. Jewish

rebellion against Roman rule culminated in the destruction of the Second Temple

in 70 CE and the mass dispersion of Jews throughout the Roman Empire, a key

event known as the Jewish Diaspora.

During the long

centuries of the Diaspora, Jews maintained a deep connection to the land of

Israel, even as the region passed under the control of various empires,

including the Byzantine, Islamic Caliphates, Crusaders, Mamluks, and the

Ottoman Empire. Despite periods of persecution and exile, small Jewish

communities continued to exist in cities such as Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and

Tiberias. Yet, the majority of Jews lived in Europe, North Africa, and the

Middle East, maintaining their religious and cultural traditions while yearning

for a return to their ancestral homeland—a central theme of Jewish prayer and

identity.

By the late 19th

century, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, which had ruled the region for

centuries, signaled a new era of political upheaval and opportunity. The

region's strategic location, situated at the crossroads of Africa, Europe, and

Asia, meant that it attracted the interest of European powers, particularly

Britain and France, which sought to expand their colonial empires.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, negotiated in secret between

Britain and France, would later divide the Ottoman territories into spheres

of influence, including Palestine, where Britain assumed control after

World War I.

This period also

witnessed the rise of Arab nationalism, as the Arab population of the region,

inspired by the weakening of the Ottoman Empire and European colonialism, began

to assert its political aspirations. The desire for self-determination, coupled

with resentment towards European colonial powers, would create the foundation

for Arab resistance to the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine.

The 19th century,

moreover, saw the beginning of a new chapter in Jewish history with the

emergence of modern nationalism, particularly Zionism, as Jews in Europe faced

increasing discrimination, persecution, and the challenges of assimilation.

This rising Jewish nationalist movement would ultimately shape the trajectory

of Jewish immigration to Palestine and lay the groundwork for the creation

of the State of Israel.

The Rise of Zionism

Zionism, the movement

for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, arose in the late 19th

century in response to the twin pressures of European anti-Semitism and the

rise of nationalist movements across Europe. The term "Zionism"

was coined by Theodor Herzl, an Austrian-Jewish journalist and writer, in the

late 19 th century, though the roots

of Jewish yearning for a return to Zion (another name for Jerusalem and

the land of Israel) date back to ancient times.

Herzl, who witnessed

firsthand the virulent anti-Semitism of European society—most notably

during the Dreyfus Affair in France —became convinced that the only solution to

the "Jewish Question" was for Jews to have their own nation-state. His

landmark book, Der Judenstaati (The

Jewish State), published in 1896, laid out the ideological foundation of political Zionism.

Herzl argued that Jews, like other national groups in Europe, deserved the

right to self-determination and that this could only be achieved through the

establishment of a sovereign Jewish state in Palestine.

Zionism was not a

monolithic movement, however, and various factions emerged with differing

visions of what the future Jewish state should look like. Some early Zionists,

like Ahad Ha'am, promoted a cultural Zionism that emphasized the revival of

Hebrew and Jewish culture as Che basis for a Jewish homeland, rather than

the establishment of a political state. Others, like Labor Zionists led by

figures such as David Ben-Gurion, sought to combine Zionist ideals with

socialist principles, advocating for collective agriculture (kibbutzim) and the

building of a new Jewish society based on equality and labor.

Europe, particularly

in Russia, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This period saw the

arrival of the First Aliyah (Jewish immigration wave) in the 1880s, during

which thousands of Jews, many from Eastern Europe, settled in Palestine. These

early settlers faced significant hardships, including disease, economic

instability, and resistance from the local Arab population, but they laid the

groundwork for future Jewish immigration and state-building efforts.

The early 20th

century witnessed further waves of Jewish immigration (the Second and Third

Aliyot), as Zionist pioneers established agricultural communities and cities

like Tel Aviv, seeking to fulfill the Zionist dream of building a Jewish

homeland. The Zionist movement also began to garner support from sympathetic

elements within European society, including some Christian Zionists who saw the

return of Jews to Palestine as part of a religious prophecy.

At the same time,

Arab resistance to Jewish immigration and land acquisition began to grow. The

Arab population, which had lived in Palestine for centuries under Ottoman rule,

increasingly viewed Zionism as a threat to their land, livelihoods, and national

aspirations. Tensions between Jewish and Arab communities escalated in the

early decades of the 20th century, setting the stage for future conflict as

both groups sought to assert their claims to the land.

European colonialism

played a pivotal role in shaping the modern history of the Middle East,

particularly in the decades leading up to the founding of Israel. By the late

19th century, European powers had carved up much of the world into colonial

possessions, and the Middle East was no exception.

The decline of the

Ottoman Empire, long referred to as the "sick man of Europe/ created an

opening for European intervention in the Middle East. During World War I, the

British and French made secret agreements (such as the Sykes-Picot Agreement)

to divide the Ottoman territories into spheres of influence. Following the

defeat of the Ottomans, the League of Nations granted Britain the

mandate to govern Palestine, a development that would have lasting

consequences for the region.

The British Mandate

in Palestine, which lasted from 1920 to 1948, was marked by a delicate

balancing act as Britain tried to manage the competing aspirations of Jews and

Arabs in the territory. Britain had, through the Balfour Declaration of 1917,

expressed support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish

people" in Palestine. This declaration, while vague in its terms, was seen

by the Zionist movement as a significant step toward realizing their goal

of Jewish statehood.

However, Britain's

commitment to Zionism was tempered by its need to maintain stability in the

region, particularly as Arab resistance to Jewish immigration grew more

intense. Arab revolts in the 1920s and 1930s, fueled by opposition to Jewish

land purchases and fears of displacement, led Britain to issue a series of

White Papers that attempted to limit Jewish immigration and land acquisition.

These policies, in

turn, angered the Zionist movement, which viewed them as a betrayal of

Britain's earlier commitments.

The outbreak of World

War II and the Holocaust had a profound impact on the trajectory of Zionism and

the future of Palestine. The mass murder of six million Jews during the

Holocaust galvanized support for the establishment of a Jewish state, both

within the Jewish community and among sympathetic Western powers, particularly

the United States. The war also marked the decline of European colonialism, as

Britain and France, weakened by the conflict, began to retreat from their

colonial possessions.

In the post-war

period, international sympathy for the Jewish people, combined with the

strategic interests of the Western powers, paved the way for the United Nations

to propose a partition plan for Palestine in 1947. This plan, which called for

the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states, was accepted by the Zionist

leadership but rejected by the Arab states and Palestinian Arab leaders. The

subsequent war in 1948, which followed the declaration of the State of Israel,

resulted in the establishment of Israel and the displacement of hundreds of

thousands of Palestinian Arabs—a conflict that continues to resonate in the

region to this day, European colonialism, therefore, played a critical role in

shaping the modern Middle East and the conditions that led to the founding of

Israel. The legacy of colonialism, with its arbitrary borders, foreign

intervention, and the imposition of external political models, has left a

lasting imprint on the region, contributing to the ongoing conflicts and

struggles for national identity and sovereignty.

On November 2,1917,

British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour issued a letter addressed to

Baron Rothschild, a leading figure in the British Jewish community, whereby

also the Balfour declaration was

approved, and communicated by Balfour to Rothschild on 2 November 1917.

During a meeting of the Samuel Committee on 10 May,

Weizmann admitted that lately ‘a great deal’ had been heard ‘about the unrest

amongst Arabs and their opposition to Zionism’, but mainly blamed this on a

lack of support of the Zionist movement ‘by the Administration on the spot’, in

particular ‘the lower officials who in some cases have done a great deal of

irreparable damage’. The military authorities had apparently lost confidence in

‘the possibility or advisability of putting into effect the Balfour Declaration’,

but nothing could be ‘more unjust and short-sighted than that. Jewry is not

going to give up its claim to Palestine, and Great Britain or America is not

going back on a solemnly pledged word.’ This was precisely the line Balfour

took in a letter to Curzon on the declaration proposed by Money. There could

‘of course be no question of making any such announcement as that suggested […]

and in this connection it might be well’ to remind Clayton that ‘the French,

United States and Italian governments have approved the policy outlined in my

letter to Lord Rothschild of November 2nd, 1917’. Balfour also informed Curzon

that Thwaites had suggested that ‘it might be advisable at this stage to send

out to Palestine a further advisor on Zionist matters to assist General Clayton’ and that Thwaites had

‘proposed, in this connection, Colonel Meinertzhagen, D.S.O. as the most suitable person’. The

Foreign Office telegraphed Balfour’s observations to Clayton without further

comment on 27 May 1919.3 Clayton replied on 9 June: ‘Your remarks noted. About

Colonel Meinertzhagen, if you send him out,

he will be useful to me.’ From a later telegram, it appeared that he was not a

bit impressed by Balfour’s reminder that Britain’s allies also supported the

Zionist cause. He wired on 19 June that ‘unity of opinion among the Allied

governments on the subject of Palestine’, was ‘not a factor which tends to

alleviate the dislike of non-Jewish Palestinians to the Zionist Policy. Indeed,

it rather leads to still further anxiety on their part to express clearly to

the world their point of view.’

The Exodus of European Jews

The aftermath of

World War II brought with it a significant humanitarian crisis for the Jewish

population of Europe. The Holocaust left millions of Jews displaced,

traumatized, and without homes. Many survivors sought to rebuild their lives,

yet the conditions they faced were dire. In the years following the war, Jewish

immigration to Palestine surged as displaced persons sought refuge from the

horrors they had endured. This chapter examines the conditions in displaced

persons camps in Europe, the patterns of Jewish immigration to Palestine

post-World War II, and the impact of British immigration policies on this

influx.

Displaced Persons Camps in Europe

After the war, Europe

was littered with the remnants of the Nazi regime, and among its most tragic

legacies were the displaced persons camps. These camps were established

primarily to provide temporary shelter and assistance to Holocaust survivors

and other refugees. The camps, which sprang up across Germany, Austria, and

Italy, housed thousands of Jewish displaced persons (DPs) who had lost their

homes, families, and communities. Living conditions in these camps were

often harsh and overcrowded. Many DPs had no idea where their families were or

if they had survived the war. The camps lacked adequate sanitation, food, and

medical care. Despite these challenges, the DPs exhibited remarkable resilience

and determination. Many were eager to start anew and rebuild their lives, but

they faced significant obstacles. The question of where to go loomed large over

the displaced community, and for many, the answer lay in Palestine.

In the DP camps,

Jewish life was revitalized, albeit in an uncertain environment. Organizations

such as the Jewish Agency and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee

(JDC) provided assistance, resources, and support to help the DPs rebuild their

lives. Education and cultural activities were organized in the camps, fostering

a sense of community among survivors. Despite their trauma, many DPs began to

reassert their Jewish identity and culture, holding celebrations,

religious services, and educational programs.

The connection to

Palestine grew stronger among the displaced Jewish community in Europe. Many

DPs viewed the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine as the only

viable solution to their plight. The Zionist movement gained momentum in the DP

camps, and leaders advocated for the mass immigration of Jewish survivors to

Palestine. The aspirations of these refugees intertwined with the broader

Zionist goal of establishing a Jewish state, emphasizing the urgent need for a

haven.

Jewish Immigration to Palestine Post-World War II

The immediate

post-war years saw a dramatic increase in Jewish immigration to Palestine. As

the reality of the Holocaust sunk in and the conditions in DP camps remained

dire, Jewish survivors, spurred by the hope of establishing a new life in

a Jewish homeland, made the perilous journey to Palestine. This surge of

immigration, known as Aliyah Bet, was characterized by both legal and illegal

efforts to enter the British Mandate territory.

Illegal immigration

was a key component of this post-war influx. Many Jews, disillusioned with

British restrictions on immigration, resorted to clandestine operations to

reach Palestine. Organized by groups such as the Haganah and the

Irgun, these efforts involved smuggling Jewish refugees into Palestine

despite British naval patrols and restrictions. Overcrowded ships, often in

dire conditions, set sail from various ports in Europe, risking interception by

the British authorities.

These clandestine

operations highlighted the determination of Jewish refugees to reach Palestine.

Many ships were intercepted by British forces, leading to arrests and

deportations of Jewish immigrants back to Europe or to internment camps on

Cyprus. The British government's stringent immigration policies further

fueled tensions between the Jewish community and British authorities. Despite

these challenges, thousands of Jewish refugees successfully reached Palestine,

where they sought to establish new lives and contribute to the burgeoning

Jewish community. The urgency of the situation was amplified by the unfolding

geopolitical landscape. The establishment of the United Nations and the

subsequent recommendation for the partition of Palestine in 1947 created a

sense of optimism among Jewish leaders. The growing recognition of the need for

a Jewish state spurred greater momentum for immigration. Jewish communities in

the United States and around the world mobilized to support the cause, raising

funds and resources to facilitate the arrival of Jewish immigrants.

As the number of

Jewish immigrants surged, tensions between Jewish and Arab communities

escalated. The influx of Jewish refugees intensified Arab fears of

displacement and loss of land. Clashes between the two communities became

increasingly common, further complicating the situation in Palestine.

British Policies on Immigration and Their Effects

The British

government faced immense pressure in the wake of World War II, particularly

concerning its policies on Jewish immigration to Palestine. The aftermath of

the Holocaust highlighted the urgency of the situation and drew

international attention to the plight of Jewish survivors. However, British

authorities remained committed to limiting Jewish immigration in response to

Arab opposition and concerns about maintaining stability in the region.

In 1946, the British

White Paper reaffirmed the restrictive immigration quotas established in

previous policies. The document outlined a maximum of 150,000 Jewish immigrants

allowed into Palestine over a specified period, contingent on the approval

of Arab leaders. This policy was met with outrage from the Jewish community,

who viewed it as a betrayal of the commitments made in the Balfour Declaration.

The restrictive

immigration policies led to significant tensions between Jewish groups and

British authorities. Jewish leaders and organizations escalated their efforts

to challenge British restrictions, leading to acts of resistance, including

bombings and attacks on British installations. The situation reached a

boiling point in 1947 when Jewish paramilitary groups intensified their

campaign against British rule in Palestine, demanding an end to restrictions on

immigration and the establishment of a Jewish state.

The British government's inability to

effectively manage the escalating violence and unrest ultimately prompted them

to reconsider their position. Faced with increasing international pressure and

mounting violence.

Followed by the formation of the UN Special

Committee on Palestine, the details of the UN Partition Plan (Resolution 181),

and the reactions from Jewish and Arab communities, earlier described by

us here.

Formation of the UN Special Committee on Palestine

The United Nations

was established in 1945, following the devastation of World War II, with a

mandate to promote peace, security, and cooperation among nations. The plight

of Jewish refugees and the ongoing conflict in Palestine prompted the UN to

take an active role in finding a solution to the tensions between Jewish and

Arab communities. In 1947, the UN General Assembly established the United

Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) to investigate the situation in

Palestine and propose a plan for its future. The formation of UNSCOP came in

response to escalating violence and unrest in Palestine, particularly as Jewish

immigration surged in the aftermath of the Holocaust. The British government,

overwhelmed by the growing tensions and unable to maintain control, announced

its decision to withdraw from Palestine. Faced with this vacuum of authority,

the UN sought to provide a framework for resolving the conflicting aspirations

of Jews and Arabs.

UNSCOP comprised representatives

from various member states, including both Western and non-Western countries.

The committee's mandate was to conduct an investigation into the

situation in Palestine and consider various solutions, including the

possibility of partitioning the territory into separate Jewish and Arab states.

Members of UNSCOP traveled to Palestine to gather evidence, conduct interviews,

and consult with local leaders and communities.

During its

investigation, UNSCOP encountered a complex landscape of competing narratives

and aspirations. The Jewish community buoyed by international sympathy and the

trauma of the Holocaust, emphasized the need for a Jewish state as a sanctuary

for Jews worldwide. In contrast, the Arab community, rooted in its historical

connection to the land, expressed deep fears about losing their homeland and

their rights to self-determination.

UNSCOP faced

significant challenges in crafting a proposal that could address the grievances

of both communities. The committee recognized the urgency of the situation and

the necessity of reaching a solution that would provide a basis for

coexistence. After extensive deliberations, UNSCOP ultimately settled on the

idea of partitioning Palestine as a means to reconcile the

conflicting national aspirations of Jews and Arabs.

The UN Partition Plan: Resolution 181

On November 29, 1947,

the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 181, which recommended

the partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, along with an

international administration for Jerusalem. This landmark resolution was rooted

in the principles of self-determination and aimed to provide a framework for

resolving the ongoing conflict.

According to

Resolution 181, the proposed partition plan outlined the following key

features:

Territorial Division: The

plan designated approximately 55% of the territory of Palestine for the

establishment of a Jewish state, while allocating around 45% for an Arab state.

The partition proposal divided the land into various zones, taking into

account the demographic distribution of Jewish and Arab populations.

Jerusalem: The

city of Jerusalem was to be established as an international city, administered

by the United Nations. This decision reflected the city's significance to both

Jews and Arabs, as well as its religious importance to Christians. The plan sought

to ensure that Jerusalem remained accessible to all faiths and protected from

sectarian conflict.

Economic Union: The

partition plan proposed the establishment of an economic union between the two

states, aimed at fostering cooperation and stability in the region. This union

was envisioned as a means of facilitating trade, commerce, and mutual support

between the Jewish and Arab communities.

Minority Rights: The

resolution emphasized the importance of safeguarding the rights of minorities

in both states, mandating that both the Jewish and Arab populations be afforded

protections to ensure their civil and political rights. This provision aimed to

alleviate fears of persecution and discrimination.

The passage of

Resolution 181 marked a significant turning point in the quest for a Jewish

homeland and the future of Palestine. The resolution reflected a growing

international consensus regarding the necessity of addressing the competing

claims of Jews and Arabs and provided a formal framework for partitioning the

territory.

Reactions from Jews and Arabs

The reactions to the

UN Partition Plan were starkly divided, reflecting the deep-seated animosities

and conflicting aspirations between the Jewish and Arab communities. The

announcement of Resolution 181 triggered a wave of responses that would shape

the course of events in the region for years to come.

Jewish Response

The Jewish community

largely welcomed the UN Partition Plan, viewing it as a legitimate recognition

of their national aspirations. For many Jewish leaders, the resolution

represented a historic milestone in their quest for statehood. Prominent

Zionist figures, including David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann, expressed

support for the partition plan as a necessary step toward the establishment of

a Jewish state.

The Jewish Agency,

which served as the representative body of the Jewish community in Palestine,

officially endorsed the UN plan. The agency's leaders viewed the partition as

an opportunity to create a secure homeland for Jews, particularly in light

of the horrors of the Holocaust. The announcement of the partition plan

inspired a renewed sense of hope and determination among Jewish communities,

both in Palestine and abroad.

In the weeks

following the passage of Resolution 181, Jewish leaders mobilized to prepare

for the establishment of a Jewish state. They focused on strengthening

institutions, bolstering defense capabilities, and rallying support from the

international community. The Jewish community viewed the partition as a moral

imperative, reflecting the urgent need for a safe haven where Jews

could thrive. However, there were also factions within the Jewish community

that expressed reservations about the partition plan. Some more radical Zionist

groups, including the Irgun and Lehi, rejected the proposal outright, believing

that the partition would undermine their aspirations for a greater Jewish state

encompassing all of Palestine. They called for increased military action

against British authorities and Arab groups, asserting that a Jewish state

should be established without compromise.

Despite these

dissenting voices, the overall reaction among the Jewish community was one of

hope and determination. The passage of Resolution 181 fueled a sense of urgency

to establish the Jewish state, with plans for immigration, infrastructure, and

governance accelerating in anticipation of independence.

Arab Response

In stark contrast,

the Arab community vehemently opposed the UN Partition Plan. Arab leaders

viewed the resolution as a grave injustice that denied their rights to

self-determination and sovereignty over their ancestral lands. The Arab Higher

Committee, led by prominent figures such as Amin al-Husseini, condemned the

partition plan, asserting that it violated the principles of fairness and

justice.

The rejection of

Resolution 181 was rooted in deep historical grievances and fears of

displacement. Arab leaders argued that the proposed partition disregarded the

demographic realities of Palestine and ignored the rights of the Arab

population, who constituted the majority. The idea of partitioning their

homeland was met with outrage and disbelief, as many Arabs felt that their

national aspirations were being ignored.

In the wake of the

UN's decision, Arab leaders called for mass protests and mobilized public

opinion against the partition plan. The Arab League, formed in 1945, expressed

solidarity with the Palestinian cause and called for the rejection of any plan

that sought to partition Palestine. Arab nations, fearing the consequences of

the proposed partition, threatened to intervene militarily to prevent its

implementation.

The rejection of the

partition plan set the stage for a heightened sense of conflict and tension in

the region. As the date for the planned implementation approached, both Jewish

and Arab communities braced for confrontation. The Arab response to the UN's

decision reflected the deep divisions that had emerged in Palestinian society

and foreshadowed the violence and upheaval that would follow.

Escalation of Violence

The adoption of

Resolution 181 did not quell tensions; instead, it intensified the violence

between Jewish and Arab communities. As Jewish armed groups prepared for the

potential establishment of a Jewish state, Arab forces mobilized to oppose the

partition and defend what they viewed as their homeland. The months leading up

to the planned withdrawal of British forces and the potential declaration of

independence were marked by a series of violent confrontations.

In December 1947,

following the announcement of the partition plan, clashes erupted between

Jewish and Arab communities in various parts of Palestine. Arab attacks on

Jewish settlements and retaliatory actions by Jewish militias escalated,

resulting in casualties on both sides. The violence highlighted the deepening

mistrust and animosity that had developed between the two communities, further

complicating efforts for peaceful coexistence.

In the weeks leading

up to the British withdrawal, the situation continued to deteriorate. Armed

groups from both communities engaged in increasingly violent confrontations,

leading to widespread chaos and insecurity. The violence culminated in a series

of events known as the "Black Saturday" in April 1948, during which a

coordinated attack by Arab forces on Jewish communities resulted in significant

casualties.

The escalating

violence prompted both communities to prepare for the possibility of full-scale

conflict. The Jewish community began to organize its defenses, while Arab

leaders called for a united front against what they perceived as the imminent

threat to their existence. The stage was set for the inevitable clash that

would follow the declaration of the State of Israel.

Legacy of the UN Partition Plan

The UN Partition Plan

and the reactions it elicited marked a critical juncture in the history of

the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The resolution represented the

first international acknowledgment of the competing national aspirations of

Jews and Arabs, yet it also underscored the challenges of reconciling these

aspirations in a divided land.

The passage of

Resolution 181 and the subsequent events in Palestine laid the groundwork for

the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948. The Jewish community's

acceptance of the partition plan provided a legal basis for declaring

independence, while the Arab community's rejection set the stage for violent

conflict. The ensuing war resulted in the displacement of hundreds of thousands

of Palestinians, a legacy that continues to shape

the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to this day.

The UN's role in

proposing a partition plan also underscored the limitations of international

intervention in resolving deeply rooted national conflicts. While the plan

sought to provide a peaceful resolution, its failure to gain acceptance from

both sides highlighted the complexity of the situation and the inability to

bridge the chasm of distrust and animosity.

In retrospect, the UN

Partition Plan remains a controversial and contentious topic in discussions

about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It is viewed by some as a

legitimate effort to address historical grievances and provide a framework for

coexistence, while others see it as a symbol of injustice and a precursor to

the ongoing struggles faced by the Palestinian people.

The formation of the

UN Special Committee on Palestine and the adoption of Resolution 181 marked

pivotal moments in the trajectory of

the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The UN's efforts to address the

competing national aspirations of Jews and Arabs through the partition plan

reflected the complexities of the situation and the challenges of reconciling

deeply held grievances.

The reactions from

both Jewish and Arab communities illustrated the stark divisions that had

developed over the years. The Jewish community largely embraced the partition

plan as a pathway to statehood, while the Arab community vehemently rejected

it, viewing it as a violation of their rights. The ensuing violence and chaos

foreshadowed the tumultuous events that would unfold in the wake of the plan's

adoption.

The legacy of the UN

Partition Plan continues to reverberate in contemporary discussions surrounding

the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As the quest for a just and lasting

solution endures, the events of 1947 serve as a poignant reminder of the complexities,

challenges, and unresolved aspirations that continue to shape the region.

The Civil War (1947-1948)

The period between

1947 and 1948 was marked by escalating violence in Palestine as tensions

between Jewish and Arab communities erupted into a civil war. Following the

United Nations' adoption of Resolution 181, which proposed the partition of

Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, both communities prepared for

the impending political changes. However, the situation quickly spiraled into

armed conflict, characterized by violence between Jewish and Arab militias, key

battles that would shape the future of the region, and the involvement of

international actors seeking to influence the outcome. This chapter examines

the dynamics of the civil war, the pivotal moments that defined it, and the

roles played by external powers in this turbulent period.

Violence between Jewish and Arab Militias

As the UN Partition

Plan was approved, the situation in Palestine became increasingly volatile.

Both Jewish and Arab communities began to mobilize their militias in

preparation for the anticipated violence that would follow the announcement of

partition. For the Jewish community, this meant bolstering the ranks of

the Haganah, the primary paramilitary

organization, alongside other groups such as the Irgun and Lehi. The Arab

community, on the other hand, saw the emergence of various militia groups,

including the Arab Liberation Army (ALA), which was composed of fighters from

neighboring Arab countries.

The conflict began

with sporadic violence that quickly escalated into widespread armed

confrontations. In December 1947, following the UN's decision, the first major

clashes erupted between Jewish and Arab communities. The violence was marked by

ambushes, retaliatory attacks, and targeted killings, with both sides

committing acts of brutality that exacerbated the animosities.

Jewish militias

initially focused on securing strategic areas, particularly those designated

for the Jewish state in the partition plan. Arab groups, fueled by the fear of

losing their land and sovereignty, launched attacks on Jewish settlements and

communities, leading to an intensification of violence. Both sides employed

guerrilla tactics, and as the conflict escalated, the casualties mounted.

The situation

worsened as the fighting spread to urban centers. The city of Jerusalem became

a focal point of violence, with competing claims to control significant

religious sites. In particular, the Old City of Jerusalem, home to key

religious landmarks for both Jews and Muslims, became a battleground, and

clashes resulted in numerous casualties and considerable destruction.

As the violence

escalated, the local population became increasingly polarized. Many Jews

rallied to the cause of statehood, motivated by the horrors of the Holocaust

and the desire for a secure homeland. Conversely, many Arabs feared for their

future and felt their rights were being violated. The civil war, thus, became

not only a struggle for territory but also a fight for identity,

self-determination, and survival.

Key Battles and Turning Points

Several key battles

and events defined the civil war, marking turning points that would shape the

course of the conflict. As the violence intensified, the battle for control

over territory and resources became increasingly critical.

Operation Nachshon

In April 1948, the

Jewish community launched Operation Nachshon, aimed at securing the roads

leading to Jerusalem, which were under Arab control. The operation aimed to

lift the siege on Jewish neighborhoods and ensure access to supplies. Despite

fierce resistance from Arab forces, the Haganah was

able to capture strategic positions, leading to increased control over access

routes.

The battle for

Jerusalem culminated in the fierce fighting for the Old City, which was

primarily Arab-controlled. On May 28, 1948, Jewish forces successfully

captured the western half of the city, but the Old City, with its significant

Arab population, remained under Arab control until the conclusion of the war.

The struggle for Jerusalem illustrated the deep-seated divisions and the

emotional significance the city held for both communities.

The Safed Massacre

The city of Safed,

located in northern Palestine, became a significant flashpoint in the

civil war In April 1929, a massacre of Jews in Safed resulted in the

deaths of 18 Jewish residents at the hands of Arab mobs. This event left a

lasting scar on the Jewish psyche and fueled a sense of urgency for

self-defense and military preparedness.

In response to rising

tensions, the Haganah and Irgun launched an

offensive to secure Safed and surrounding areas. In early May 1948, they

successfully took control of the city, displacing many Arab residents. The

Safed Massacre served as a rallying cry for Jewish forces, highlighting the urgent

need for military action in the face of perceived existential threats.

The Battle of Haifa

The city of Haifa,

located on the Mediterranean coast, was another critical battleground during

the civil war. The strategic importance of Haifa lay in its port, which was

vital for the importation of supplies and arms. The city's population included

a significant number of both Jews and Arabs, making it a flashpoint for

conflict.

In April 1948, as

tensions escalated, Jewish forces launched an operation to secure Haifa.

The Haganah, supported by the Irgun, attacked

Arab neighborhoods, leading to fierce fighting. The battle culminated in the

capture of Haifa on April 22, 1948. The fall of Haifa resulted in the

displacement of a large portion of the Arab population, as many fled amid the

violence and chaos.

The capture of Haifa

was significant not only for its strategic value but also as a psychological

victory for Jewish forces. It demonstrated the growing military capabilities of

the Jewish community and their determination to secure their future in Palestine.

The Role of International Actors

Throughout the civil

war, various international actors played a role in shaping the course of events

in Palestine. The geopolitical context of the post-World War II era influenced

the actions and responses of both the Jewish and Arab communities.

British Policy and Withdrawal

As violence

escalated, British authorities found themselves in a precarious position. After

World War II, Britain faced mounting pressure to address the growing

humanitarian crisis and the urgent need for a resolution in Palestine. However,

the British government remained conflicted, caught between the demands of

Jewish leaders for statehood and Arab opposition to partition.

In early 1947, the

British government announced its intention to withdraw from Palestine,

effectively relinquishing its mandate. The withdrawal created a power vacuum

that further fueled the conflict. As British forces began to evacuate, tensions

mounted, and both Jewish and Arab militias seized the opportunity to assert

control over key territories.

The British

withdrawal ultimately set the stage for the declaration of the State of Israel

and the subsequent Arab-Israeli war. The absence of British authority

led to a complete breakdown of law and order, exacerbating the violence and

chaos.

U.S. Involvement

The United States

played a crucial role in shaping the political landscape during the Civil War.

In the aftermath of World War II, the U.S. was increasingly supportive of the

Zionist movement and recognized the need for a Jewish state, particularly in

light of the Holocaust and the plight of Jewish refugees.

The U.S. government

offered political support for the UN Partition Plan and advocated for Jewish

immigration to Palestine. As the civil war escalated, American leaders faced

pressure to intervene diplomatically and provide support to the Jewish

community. American public opinion largely favored the establishment of a

Jewish state, and many humanitarian organizations worked to assist Jewish

refugees and immigrants.

However, the U.S.

also faced challenges in its relationships with Arab nations. As tensions grew,

U.S. policymakers sought to balance their support for the Jewish community with

diplomatic relations with Arab states. This balancing act would become increasingly

complicated in the lead-up to the establishment of the State of Israel.

Arab League Intervention

In response to the

increasing violence and the impending declaration of the State of Israel, the

Arab League took decisive action. The organization, which was founded in 1945

to promote cooperation among Arab nations, expressed solidarity with the Palestinian

cause and sought to prevent the partition of Palestine.

On May 15, 1948,

following the declaration of independence by Israel, neighboring Arab

countries, including Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Iraq, launched a military

intervention against the newly formed state. The Arab League's intervention

aimed to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state and protect Arab interests

in Palestine. The military campaign marked the beginning of the

first Arab-Israeli war, fundamentally altering the trajectory of the

conflict.

The civil war in

Palestine from 1947 to 1948 marked a critical juncture in the struggle for

national identity, self-determination, and statehood for both Jews and Arabs.

The violence between Jewish and Arab militias reflected deep-seated historical

grievances and competing national aspirations. Key battles, such as those

in Jerusalem, Safed, and Haifa, highlighted the fierce struggle for territory

and control.

The role of

international actors, including the British government, the United States, and

the Arab League, shaped the course of the civil war and influenced the outcomes

of critical events. The withdrawal of British forces and the subsequent

military intervention by Arab states set the stage for the establishment of the

State of Israel and the transformation of the geopolitical landscape in the

region.

As the civil war

concluded, the implications of this period would reverberate for decades to

come. The conflict resulted in the displacement of hundreds of thousands of

Palestinians and laid the foundation for a protracted struggle that continues

to define the Israeli-Palestinian conflict today. The legacies of the

civil war, the aspirations for statehood, and the ongoing quest for peace would

shape the trajectory of both Israeli and Palestinian identities in the year to

come.

The Declaration of the State of Israel

On May 14, 1948,

David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, proclaimed the establishment

of the State of Israel. This momentous event marked the culmination of decades

of Zionist aspiration, encapsulating the dreams and struggles of the Jewish

people for a homeland following centuries of persecution and displacement. The

declaration of independence came in a climate of violence, uncertainty, and

geopolitical upheaval, setting the stage for both celebration and conflict.

This chapter explores BenGurion's leadership,

the political processes that led to the declaration, and the international

recognition and reactions that followed.

Ben-Gurion's Leadership

David Ben-Gurion

emerged as a key figure in the Zionist movement and the eventual establishment

of Israel. Born in 1886 in Plonsk, Poland, he

immigrated to Palestine in 1906 and became deeply involved in the Jewish labor

movement and the Zionist cause. As a staunch advocate for Jewish statehood,

Ben- Gurion's leadership style was characterized by determination, pragmatism,

and a profound commitment to the Zionist vision.

Throughout the

tumultuous years leading up to the declaration of independence, Ben-Gurion

played a pivotal role in uniting various factions within the Jewish community.

He worked to forge a consensus among the different political and social groups,

from the leftist Mapai party to more militant factions like the Irgun and Lehi.

His ability to navigate these complex dynamics was crucial in fostering a

unified front in the face of external threats.

Ben-Gurion was

acutely aware of the historical moment and the necessity of declaring statehood

before the impending withdrawal of British forces. He argued that the Jewish

community must act decisively to establish a sovereign state, as it represented

not only the culmination of Jewish aspirations but also the only viable means

to ensure the safety and survival of Jews in the region.

As the civil war

intensified, Ben-Gurion convened meetings with other Jewish leaders to prepare

for the declaration. He emphasized the urgency of the situation, stressing that

a formal declaration of independence would legitimize the Jewish claim to statehood

in the eyes of the international community. On the eve of the declaration, he

sought to balance the aspirations of the Jewish community with the realities on

the ground, acknowledging the fears and grievances of the Arab population while

resolutely pushing forward with plans for statehood.

On May 14, 1948,

Ben-Gurion delivered the historic declaration in a ceremony at the Tel Aviv

Museum. His speech articulated the deep historical connection of the Jewish

people to the land of Israel and affirmed the commitment to building a

democratic state that would uphold the rights of all its inhabitants. The

declaration resonated with a sense of urgency, hope, and determination,

capturing the emotional weight of the moment.

In April 1948, the

Jewish community launched Operation Nachshon, aimed at securing the roads

leading to Jerusalem, which were under Arab control. The operation aimed to

lift the siege on Jewish neighborhoods and ensure access to supplies. Despite

fierce resistance from Arab forces, the Haganah was

able to capture strategic positions, leading to increased control over access

routes.

The battle for

Jerusalem culminated in the fierce fighting for the Old City, which was

primarily Arab-controlled. On May 28, 1948, Jewish forces successfully

captured the western half of the city, but the Old City, with its significant

Arab population, remained under Arab control until the conclusion of the war.

The struggle for Jerusalem illustrated the

deep-seated divisions and the emotional significance the city held for both

communities.

For updates click hompage here