By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Ukraine And U.S. National Security

The war in Ukraine

has sparked a puzzling development in U.S. national security thinking. At the same

time as U.S.-European cooperation has surged, an influential group of American

scholars, analysts, and commentators have begun pressing the United States to

prepare to scale back its commitment to Europe radically. The basic idea is not

new: restraint-oriented realists have long called

for the United States to rethink its security posture in Europe.

However, they have

been joined by an influential band of China hawks, who argue that the United

States must curb its European commitments. The primary contest, this group

believes, is in the Indo-Pacific, against China—and

Washington must focus all its resources on that confrontation.

The specific wishes

of these realists and hawks are often vague, combining ill-defined cuts to U.S.

forces in Europe with demands for Europe to step up its security without

necessarily calling on Washington to ditch NATO outright. But if the United

States is to reduce its obligations to NATO, to go all-in on the China threat,

as they argue it should, it will have to slash its forces in Europe and at

least raise the possibility of pulling away from the alliance.

On a conceptual

level, this idea is bold and thought-provoking. In theory, Washington can

significantly bolster its Indo-Pacific posture by empowering allies to take the

lead in Europe and liberating U.S. resources for use in Asia. But a closer look

at the dynamics in the play shows how self-defeating such a shift would be in

practice. Instead of strengthening Washington’s hand in Asia, the result could

weaken the United States' growing competition with China.

Apples And Oranges

To begin with, the

tradeoff between Europe and the Indo-Pacific is less significant than some

skeptics suggest. The military needs of the two regions are quite different.

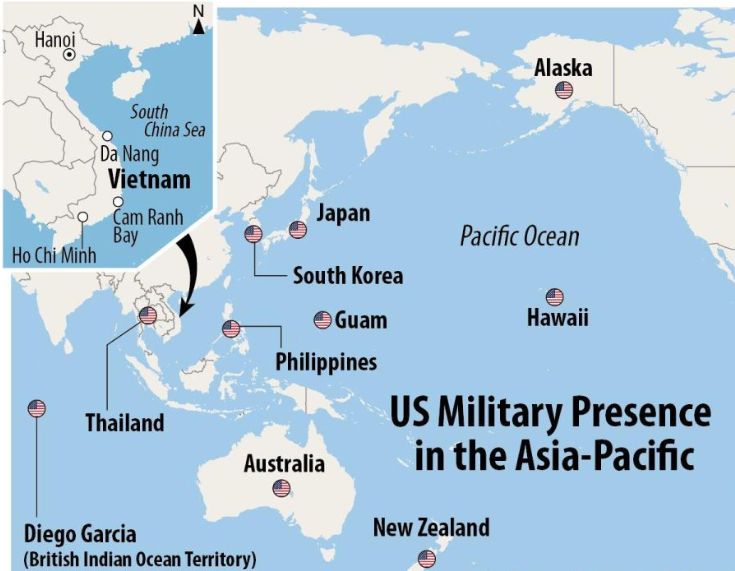

Because of its vast distances and maritime orientation, the Indo-Pacific

primarily requires ships and airplanes, not ground forces of the sort that

Europe needs. Both theaters place demands on standard capabilities, including

air and missile defense and advanced munitions. Still, the Defense Department is

buying more, and allies can help in these areas.

The long-standing

charge that the United States needlessly lavishes resources on Europe is also

mistaken. In 2018, for example, one estimate of the total cost of U.S.

contributions to NATO budgets, U.S. forces in Europe, European Deterrence

Initiative programs, and security assistance came to about $36 billion, less

than six percent of the U.S. defense budget that year. With the Biden

administration’s decision to deploy roughly 20,000 additional troops to Europe

after February 2022, that bill has grown, but only temporarily. The 2024

defense budget is $842 billion, of which the United States European commitments

represent only a tiny fraction.

Advocates of

disengagement from Europe often ignore an uncomfortable fact. The only way to

save significantly on European commitments would be for the United States to

take the most extreme and risky step of leaving NATO—a step few, if any, of the

Europe critics recommend. It would, however, be necessary: no other measure

would lead to significant reductions. If, for example, the United States were

to seek merely to reduce its presence in Europe but stay in NATO, it would

still need to maintain sufficient forces and capabilities to fulfill its NATO

obligations. The U.S. defense bill would not shrink by much.

Polish and American tanks near Orzysz,

Poland, May 2023

U.S. interests

preclude any complete separation from Europe. Consider what would happen if the

United States were to leave NATO to focus on the Indo-Pacific, and then Russia

decided to attack one of the Baltic countries or Poland. It is inconceivable

that a U.S. president could sit by and do nothing as Europe fought for its life

against a brutal autocrat. Such inaction would be particularly implausible if

Russia got significant help from China, the power the United States had pivoted

to challenge. If a European war will almost certainly draw in the United

States, then the best way to avoid massive costs and risk is not to penny-pinch

on peacetime commitments. The most cost-effective option is to stay, strengthen

existing alliances, and keep war from happening in the first place. Moreover,

the growing partnership between Russia and China means that Europe and the

Indo-Pacific are now inextricably linked. However much the United States may

wish to prioritize one region over the other, backing off from Europe will

empower Russia, China’s primary partner, and ally, even as it feeds Beijing’s

narratives about U.S. decline and the triumph of autocracy.

The proposal to move

troops from Europe to reinforce the Indo-Pacific misreads the requirements for

deterrence. China is most likely to attack Taiwan if it becomes desperate,

believing it will lose any hope of unification if it fails to act. Beijing is

unlikely to be deterred by modest additional capabilities shifted from Europe

at such a moment. Indeed, such a redeployment could quickly spark Chinese

escalation by signaling the beginning of a more determined phase of U.S.

efforts to “contain” China. In other words, the dramatic demonstration of U.S.

disengagement from Europe to reinforce its Indo-Pacific military presence could

induce war rather than deter it.

Membership Has Its Privileges

The United States

also derives various benefits from NATO membership that contribute directly to

its global military effectiveness, including in the Indo-Pacific. Washington’s

cooperation with European allies in areas including coordinated ballistic

missile defense operations enhances capabilities that the United States can use

to address threats beyond Europe. U.S. participation in NATO exercises—for

example, training in Arctic areas with Finnish and Norwegian troops or

practicing amphibious operations with Sweden—improves U.S. forces’ skills.

NATO’s vigorous response to threats, including disinformation campaigns, has

generated insights that inform U.S. and partner responses elsewhere through

intelligence sharing, joint planning and exercises, and combined analysis. NATO

allies are also developing capabilities for joint intelligence and targeting in

a shared battle space, likely to offer critical lessons for similar initiatives

in the Indo-Pacific. Finally, NATO has begun work on combating cyberwarfare,

announcing a Comprehensive Cyber Defense Policy, forming Cyber Rapid Reaction

teams, and building a Cyber Defense Center of Excellence in Estonia, to share

intelligence, develop standard plans and norms for cyber defense, and engage in

shared training and exercises.

The advantages that

NATO offers Washington are not confined to Europe. Indeed, it is increasingly

evident that the United States would call on NATO for assistance in the event

of a clash in the Indo-Pacific. Although it has often been assumed that the

alliance would be a bystander to wars elsewhere, a major conflict with

China will challenge those assumptions. As described by defense experts

including Jeffrey

Engstrom, Mark

Cozad, and Tim Heath,

Chinese military doctrine calls for paralyzing blows against an enemy’s military,

social, and political systems at the war's outset. Such attacks could well

reach into the continental United States, which would, at least in theory,

provide grounds for NATO’s leaders to invoke Article 5, requiring the

alliance’s other members to assist Washington. Indeed, there is a precedent for

such a request: NATO invoked Article 5 after the 9/11 attacks on the United

States.

The general belief

has been—and rightly remains—that European governments will be eager to avoid a

U.S.-China conflict. This desire was made plain by French President Emmanuel

Macron’s statement in early April that Europe should not get “caught up in

crises that are not ours.” But a massive strike on U.S. forces or on the United

States itself may leave European leaders with little choice but to help in some

way. And over the last few years, America’s European allies have edged closer

to open support for U.S. commitments in the Indo-Pacific. Several NATO members,

including Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom,

have sent ships to the Indo-Pacific. In 2021 alone, there were 21 such

deployments. In recognition of the Chinese threat, NATO has also been deepening

its institutional partnerships with Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South

Korea. Not all of these deployments are surprising. France has long been in the

Indo-Pacific and still has over 7,000 troops. The United Kingdom also has

historical ties to the region. Its membership, with Australia and the United

States, in the trilateral security pact AUKUS has bound it directly to

Indo-Pacific security. Formal NATO strategy documents have been increasingly

explicit in identifying China as a threat.

These commitments

remain highly conditional, and NATO members, with smaller navies and air forces

and persistent European and Mediterranean responsibilities, could only send

modest forces to the Indo-Pacific. Even during an invasion of Taiwan, many

European allies may choose to restrict their help to noncombat roles. But such

support can be critical in numerous ways: sharing intelligence; cooperating in

cyber defense; ramping up munitions production; providing logistical, medical,

and other support functions; and potentially deploying symbolic units to other

Indo-Pacific countries. Such assistance could relieve the United States of

other responsibilities, fill gaps, and send powerful signals about a unified

response to further aggression.

Close coordination

with Europe is also critical to the United States’ efforts to oppose China’s

campaign to dominate the international system's norms, rules, and institutions.

The United States cannot do this alone. European support on many emerging

issues—from climate and cyber threats to artificial intelligence—will be

essential to ensure that these norms are not set in ways that undermine shared

interests. True, cooperation would continue if the United States left the

alliance. But the injured prestige, feelings of abandonment, and political

blowback that would erupt if Washington were perceived to be cutting Europe

loose would disenchanted European governments more determined to carve out a

course independent of U.S. goals. Finally, others will watch any U.S.

uncoupling from Europe and draw conclusions. Washington could hardly expect

Indo-Pacific governments to place their trust in a nation that had breached its

commitments to its staunchest allies. Beijing would doubt whether the United

States, which had deserted Europe, would make good on its pledge to defend

Taiwan.

Me Too, Not Me First

The proposal to

disengage the United States from Europe misreads the current strategic moment.

Since World War II, the United States has made a case for its international

role as the sponsor of a shared order of mutual benefit. After two decades of

threats to U.S. standing—from Iraq to the financial crisis, “America first” to

Afghanistan—coordinating responses to Russian aggression in Ukraine has

reaffirmed the value of American leadership.

Stripping, or even

significantly downgrading, the United States European commitments would

demolish much of this accumulated legitimacy. It would validate the grim

picture that China and Russia are painting the United States, which is

pitilessly self-interested and transactional. It would severely undermine the

United States painstaking attempts to build a reputation as that rare great

power offering something other than naked ambition to the world. The country’s

chief competitive advantage in the contest with China is its dominant global

network of friends and allies. Now is the time to strengthen those coveted

ties—in Europe and elsewhere.

For updates click hompage here