By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

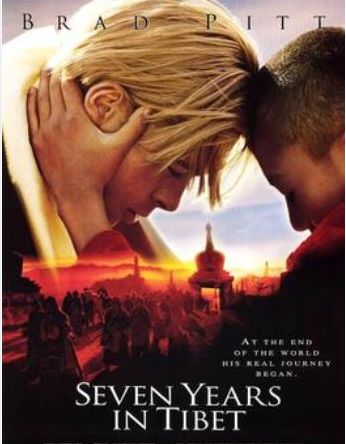

As we have seen, the

case of Seven Years in Tibet was the first clash of Hollywood moviemaking with Chinese politics. Whereby only

a few people know the actual history behind the movie.

The history behind the

movie

In March 1938, Schaefer had traveled to London to obtain permission to

enter Tibet through Assam. The Foreign Office turned him down for reasons of

"Himmler's unrest." Schaefer was told to

apply first to Tibetan authorities (“our normal way”) in the secure knowledge

that the Tibetans would not assent unless strongly backed by the British. The

Tibetan Government's negative reply reached London in May. Meanwhile, in April,

the British Ambassador in Berlin alerted the Foreign Office to Schaefer's press

reports, written as the team “was about” to embark "from Genoa" on

the Gneisenau, that the expedition was under Himmler's patronage, that al its members were SS men, and that its work “will be

carried through entirely on SS principles.”

There is no doubt that Himmler and those in “the Ahnenerbe,”

including possible Schaeffer himself although he specifically denied it, were

steeped in pseudoscientific ideas. For example the belief, in the existence of

an “Aryan race,” by standards of modern genetics is an impossibility.

A chorus of influential Britons pressed the Viceroy in India, Lord

Linlithgow, to let the Germans win.

Geheimnis Tibet

"I had to promise both the viceroy of India as well as the head of

the foreign affairs of the British-Indian central government at Simla and the

political officer at Gangtok not to cross the Tibetan border. Not, as they

(who) considered it to be properly expressed it: "Without official

leave."

However, once Himmler decided to make it a public event, he financed

the return flight to Munich Airport. Ernst Schaefer was awarded an SS

death's-head ring and applause from Himmler at the banquet upon arrival from

the airport.

Shortly after the arrival, Himmler suggested plans to next send 30

heavy-armed SS-Elite troops on a new expedition with Schaefer to Tibet, aiming

to lead the "Tibetan army" in a fight with British soldiers in India.

For this revolt, they counted on help from Nationalist revolutionaries inside

India.

When the Japanese overran the Burma Road between India and China, it

had become necessary to ship supplies to the Chinese leader, Chiang

Kai-shek," by air over the Himalayas; the "hump" route, as it

was known, was proving to be very dangerous.

Meanwhile, Schäfer had traveled to the US to complete his contract with

the Academy at Philadelphia, where he began to be bombarded by telegrams from

Berlin. The first congratulated him on his success; a second, from Himmler's

office, told him that he had been awarded an honorary promotion to 'SS

Untersturmführer Honoris causa.'

Schäfer was flattered and

replied:

I am so proud and happy I am not able to express it. I hope I will be

able to show my gratitude through my actions. All my expectations were in each,

and every respect exceeded though the greatest honor for me is to have been

promoted…

Schäfer immediately sailed back to Germany on the SS Bremen, arriving

in Hamburg. His father met him, who warned him, 'Be as clever as a snake. It is

perilous.'

Schäfer met Himmler, and the two discussed plans for a German

expedition to Tibet. Himmler was enthusiastic, as Schäfer himself recounted:

Having been a member of the Black Guard for a long time, I was only too

glad that the highest SS leader, a very keen amateur scientist, was interested

in my exploration work. There was no need to convince the Reichsführer SS, as

he had the same ideas; he promised to give me all the help necessary.

As Schäfer's plan took shape, Himmler began to pressure him to recruit

team members from within the Ahnenerbe. Himmler wanted staff on board to

investigate his pet theories in the Himalayas. Another was looking for the

Aryan homeland and examining Hörbiger's Welteislehre (World Ice Theory). At

their first meeting, Himmler told Schäfer about the theory and of how the

supernatural ancestors of the Aryans had once been sheathed in ice before being

released from their frozen bondage by divine thunderbolts.

By keeping a distance from what he quietly considered the cranks of the

Ahnenerbe. He decided next to try to decouple his work from the Ahnenerbe

altogether. To do this, Schäfer ensured that the detailed plans for the

expedition, which he had to present to Wolfram Sievers, head of the Ahnenerbe,

were on such a scale that the organization could not afford thus leading them

to reject him rather than him rejecting them. In this he was again successful;

Sievers rejected the project proposal, stating that 'The task of the expedition

… had diverged too far from the targets of the Reichsfuhrer SS …' and that in

any event the Ahnenerbe seemed to have no available funds, and nowhere near the

60,000 RM that Schäfer needed. Himmler was unhappy, but he could do nothing;

Schäfer had successfully detached himself from the Ahnenerbe without losing

Himmler's support.

Schäfer had achieved what he wanted, although he now had to raise the

money to fund the expedition himself.

Himmler had been happy to lend his name to the project as an official

patron, but Schäfer's business connections seem to have been more important.

This suggests that the father and son had collaborated in extracting the

project from the grip of the Ahnenerbe from the

beginning.

Schäfer also had to compromise in the area of science. The quest for a

Nordic empire in central Asia was not, on the face of it, Schäfer's obsession.

He was a zoologist by training, and his aim was to use the expedition to

further his research in zoology and botany, as well as in geology and

ethnology. In contrast, Himmler's priority was to support the occult racial,

anthropological, and archaeological theories of the Third Reich through the

study of the Ayran race and the associated World Ice Theory. There was,

however, some convergence.

The fact that the same kind of animals appears simultaneously in Europe

and the Rocky Mountains region has long been strong evidence for the hypothesis

that the dispersal center is halfway between. In this dispersal center, during

the close of the Age of the Reptiles and the beginning of the Age of the

Mammals, there evolved the most remote ancestors of all the higher kinds of

mammalian life which exist today…Schäfer embraced this idea of a central Asian

dispersal center.

Dr Bruno Beger was a willing member of both the expedition and the SS.

He was an anthropologist who later infamously went on to work at Auschwitz. He

worked there under Professor Hirt on behalf of the Ahnenerbe, tasked with the

collection of 115 human skeletons for inclusion in the Nazi Anthropological

Museum. Gruesome as that may sound, what marked out Beger for all time was that

he selected the 'skeletons' while their Jewish, Polish, and Asiatic owners were

still alive and held captive at Auschwitz. The 'specimens' were transported to

the Natzweiler concentration camp, where they were murdered in such a way as to

avoid damaging the skeleton. The bodies of these poor souls were then shipped

out for scientifically managed decomposition. Beger seemed to excel at this

nasty trade, and while he was collecting over 100 'Jewish Commisar' skulls for

the Berlin Institute, he still found time to supply his old friend Schäfer with

a collection of Asian skulls.

At the time of the Tibet Expedition, Beger was head of the RuSHA's Race

Division (Abteilungsleiter für Rassenkunde), and in order to leave this post,

he joined Himmler's personal staff as a Referentstelle (consultant). For the

moment, he confined himself to non-lethal examinations and the collection of

measurements, photographs, and plaster casts. The text of Geheimnis Tibet shows

that Schäfer and Beger shared the same ideas about race; when Schäfer discussed

the Nepalis, he described them as 'part Indo-Aryan, part Mongoloid’,

'intellectually very superior', and 'biologically robust'. Beger's approach was

very much that of the nineteenth-century anthropologist. As European nations

had conquered the world, anthropologists saw that the new colonies offered a

unique scientific opportunity as laboratories of human types and different

races. Indigenous peoples were measured, photographed, and collected using

calipers and cameras to measure and record. While other colonists sent back

material bounty, the scientists returned to their museums bearing cases packed

with trophy animals and sometimes trophy people.

In the end, Schäfer became increasingly concerned that the

expedition would find itself interred by the British, given the war in Europe.

In Berlin, Himmler had no desire to see his precious Tibet Expedition interned,

and so he organized their return. Arriving in Calcutta, the Germans boarded a

British Indian Airways Sunderland flying boat, which flew them from the Bay of

Bengal to Baghdad, where they found a Junkers U90 waiting to fly them on to

Vienna. From there, a U52 took them to Munich, where they were met by Himmler

himself. They all then flew to Berlin for a celebration and reception where

Schäfer was presented with a Totenkopfring by Himmler. He would not publish his

findings until 1950, under the title Festival of the White Gauze Scarves: A

Research Expedition through Tibet to Lhasa, the Holy City of the God Realm.

Some of his more sensational findings found their way into the German press

straight away, where the public avidly lapped them up.

Following the celebrations, the members of the expedition were quickly

assigned to duties fighting in the war. Himmler had something different in mind

for Schäfer - a secret military plot. It was another piece of evidence to

suggest that Schäfer had been a spy all along. The plan was for Schäfer to

return to Tibet in order to incite rebellion against the Raj. Lord Curzon would

have immediately understood the Soviet Union's interest in such a plan; it was,

after all, his fear of Russian ambition that made him send Younghusband and his

'escort' to Lhasa in 1903. Germany too had a historic interest in playing the

'Great Game', and Schäfer's plot would be one of the last hands to be played.

It might seem obvious that on the eve of war, a German expedition

traveling to Tibet, sponsored by Himmler, might be interested in plotting

against the enemies of the Reich. However, Schäfer and Beger always denied that

their work was anything other than scientific. The evidence suggests otherwise.

Schäfer went behind the back of the British by illegally crossing into Tibet

and negotiating with the Tering Raja, who disliked the British. As war became

certain, Schäfer realized that his personal friendships with the Tibetan regent

and Lhasa nobility could be of strategic value. The expedition became aware

that some Tibetans were very hostile to the British; the Regent even asked if

Schäfer could supply him with rifles, a request that was rejected. However, by

1940, that request had been reconsidered. In a letter on 12 January 1940, he

wrote: 'The political group has to be equipped with machinery, guns and 200

military firearms that I promised to the regent of Tibet'. So, either Schäfer

dissembled even to his own colleagues, or he contacted the Regent again after

September. Either way, it is a damning statement.

Schäfer was aware that there was a long tradition of Germans inspiring

indigenous people to topple the hated British Empire. The German government had

frequently used 'scientific expeditions' as a cover for espionage. Schäfer

called the plot he hatched with Himmler' The Lawrence Expedition', and this is

a clue to the origins of the idea. The Lawrence to which he referred was not T.

E. Lawrence 'of Arabia', who had masterminded the Arab Revolt against the Turks

during the First World War, but a German Lawrence, a man called Wilhelm

Wassmuss (1880–1931). The story of Wassmuss had inspired the novelist John

Buchan to write Greenmantle and had been recounted by Christopher Sykes in

1937.

MI5's director, Captain Vernon Kell, had retrieved from India

Office files the Wassmuss diaries (which had been captured in Persia,

but which, when finally in London, had been ignored for months), and the

accompanying German secret ciphers. Once Kell drew the diaries to the attention

of the India Office, the India Office was alarmed; it seemed there was active

German espionage being conducted in Persia against the Empire. The India Office

agreed that a fleet of armored motorcars under the charge of British officers

and non-commissioned officers of General Dunsterville's party should

be established at the southern end of

the Kasr-i-Shirin-Kermansha-Hamadanroad, and should gradually extend its

operations northwards in the direction of the Caspian as circumstances permit.

For updates click hompage here