By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Singapore and 'Asia'

In Singapore, the imposition of unity

and conformity has been supervised closely by a leadership imbued with a strong

sense of its unique capacity to create a well-ordered political, social, and

economic structure resting on a high degree of harmony and consensus.

Singapore's authoritarian governance has been both concealed and justified

by its Confucianist style of politics.

Lee Kuan Yew, who laid the

foundations of a system and also his son as Singapore's third Prime Minister

continued this appropriation of Confucius, seeking to defend illiberalism by

grounding it in an appeal to ancient and ineffable Chinese traditions.

Nonetheless, when seeking to wrest sovereignty from British colonial

control, Lee Kuan Yew had recourse to universal civil and

political rights, such as the freedom to organize and to hold peaceful

protests. And he aptly warned: 'Repression is a habit that grows’. And so it

has grown in Singapore, where the defense of universal human rights has been

reversed, replaced by a questionable and politically convenient invocation of

'local' values. Elections in Singapore are tightly controlled to minimize

opportunities for genuine competition. Individuals who run against People's

Action Party (PAP) candidates, and electorates that vote them into parliament,

suffer the consequences at the hands of a government with very little tolerance

for such behavior. The ruling party punishes electoral districts that do not

toe the line while opposition politicians are harassed and intimidated

relentlessly. The Internal Security Act - with its provisions for indefinite

detention without trial has sometimes been used against political opponents.

But the civil law has proved just as useful, with PAP figures successfully

prosecuting defamation cases and bankrupting opponents in previous years.1

Lee Hsien Loong

Also, aspects of public and private life

are controlled through education, health, housing, employment, pensions, and

the regulation of associational life. Not surprisingly, the government rejects

the concept of 'civil society' in the sense that this is a social space free of

government regulation or surveillance. In its place, we find a concept of

'civic society' emphasizing duties and obligations to the community rather than

'individual rights'. Explanation of the differences between 'civic' and 'civil'

in formal discourses in Singapore are phrased in terms of communitarian versus

individualistic values and practices. Civic values are of course those depicted

as communitarian, emphasizing 'self-help, social responsibility and public

courtesy' and working for the 'larger good of society'. Civil values, which

include individual rights such as free speech, are depicted as far less worthy

and representative only of 'special interests'.2

Singapore's political system has

deployed culture in general, and Confucianism in particular, as a political

tactic against the legitimacy of political opposition. This must be understood

against the background of rapid economic change in Singapore since full

independence in 1965, and the social and political consequences of such change.

In the early post-independence period, modernization was vigorously promoted

and 'traditional cultural values' were regarded as inhibiting the attitudes

needed to create an economically robust state. After just a decade and a half,

however, the PAP perceived that it could well fall victim to its own success,

for modernization very often meant political liberalization as well. Attention

therefore shifted to readjusting official ideology and, with it, the

cultural/political orientation of the population to achieve modernization sans

liberalization.

A major turning point came when the

PAP's share of the popular vote started to decline. By the late 1970s Prime

Minister Lee began to express public concern about too much 'Westernization'.

This included the development of a more open, critical public political culture

manifest in the electorate's growing willingness to listen to a variety of

alternative ideas about politics and government and to vote for opposition

candidates. Particular attention was given to the 'problem' of the Singaporean

Chinese, with Lee Kuan Yew expressing concern about the corrosive

effects that Western influences were having on this population group.3

Singaporean Chinese, viewed as

especially vulnerable to the insidious effects of Western culture, therefore

became a priority for re-education. Since they also constituted around

three-quarters of the population, with Malays, Indians, and other smaller groups

making up the remainder, they happened to be politically the most significant.

Thus traditional Confucian ethics were recruited to bring the ethnic Chinese

firmly back under the ideational control of the government. In as far as

Confucianism is Chinese, Singaporean Chinese could be expected to feel a

'natural' affinity with it. This project was difficult to promote, however,

partly because Singaporean Chinese had never had any particular familiarity

with Confucian teachings.4 Nonetheless, the stereotypical equation of

Confucianism with Chineseness

worked well, if measured by the degree of tacit acceptance with which it was

met. In 1983 the Institute of East Asian Philosophies (IEAP) was founded to

advance the understanding of Confucian philosophy so that it could be

reinterpreted to meet the needs of contemporary society.5

Elements of harmony, consensus, and

society before self - the very essence of what was later to become the core of

'Asian values' were emphasized as culturally authentic and explicitly

contrasted with the dissent and individualism said to mark Western liberal

democracies. One IEAP scholar proposed to dispense with the oppositional

elements of democracy altogether, arguing that 'the genuine consent of the

people going through the process of selection in a one-party state is ...

democratic' and that whereas Western democracy allowed debate both inside and

outside government, the 'Eastern form of democracy' allowed the government to

reach a consensus 'through closed debate with no opposition from without'.6

The PAP nonetheless wanted Singapore to

be called a democracy, thus shoring up its credentials as a modern state

commanding respect in the international sphere where no state could call itself

authoritarian. Postcolonial states such as Singapore had argued for

independence based on self-determination and all the normative implications

this principle has for democracy. But substance generally mattered less than

appearances. In Singapore, as in other authoritarian states, the challenge for

the PAP in the postcolonial order was to revise democracy so as to retain the

formal institutions while eliminating any substantive challenges to their

monopoly of power. The very civil and political liberties so passionately

argued for under British colonial rule were now repudiated at the point of

inconvenience to new power-holders. There is nothing new in partisanship and

self-interest defeating a general principle. What is of interest here is how

particularistic cultural principles were harnessed to this cause.

Regardless of the actual lack of

Confucian knowledge or understanding among the Singaporean Chinese, the fact

that a quarter of Singapore's population was not ethnically Chinese meant that

those belonging to ethnic minority groups were alienated by the emphasis on

what was seen as a purely Chinese program. Precisely because Confucianism was equated

with Chineseness, it could not neutrally embrace a population that was

also Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, Sikh, and so on. However, the

political project of creating a set of values to contrast with those of the

West could not be abandoned. Confucianization therefore

gave way to a 'shared national values' campaign. Again this was initiated and

closely supervised by the PAP government, being formally introduced in a white

paper entitled 'Shared Values' released in 1991. In addition to stressing the

dangers of 'Western values, four key values were identified as common to all

the major 'Asian' traditions: 'the placing of society above self; upholding the

family as the basic building block of society; resolving major issues through

consensus rather than contention; and stressing racial and religious harmony'.7

Dr Mahathir bin Mohamad

The set of Confucian values promoted

earlier was therefore transformed into a set of generic' Asian values'.

Packaging what was simply a very conservative set of social and political

values was not only more suitable for Singapore's diverse population but more

readily available elsewhere in the region, especially

in neighboring Malaysia where the then Prime Minister, Dr Mahathir bin Mohamad was keen to promote Asian

values as the basis for his particular brand of anti-Westernism while shoring

up the legitimacy of his political position. Since then, the Asian values

discourse has moved back and forth between a narrower focus on 'Confucian values'

and the broader Asianist approach, depending on the country concerned

and the audience. But Confucianism, like any relatively complex system of

thought, whether embodied in religions like Islam and Christianity or

ideologies like socialism and liberalism, contains ambiguities and

contradictions accommodating a variety of interpretations.

Interpreting

Confucius 'Confucianism' names a complex set of ideas almost universally

assumed to have originated with a historical figure known in English as

Confucius, otherwise rendered as Kongzi,

Kung Ch'iu, Kung Tzu, or K'ung Fu-tzu. A native of Shandong province, Confucius

is thought to have lived during the transition from the Spring to Autumn period

of the Zhou Dynasty from around 551 to 479 Be, when chaos and disorder attended

the breakdown of political and social order. The original teachings attributed

to Confucius - contained largely in the collection of sayings known as The

Analects or Lunyu - reflect a concern with

establishing lasting peace and harmony in social and political life. It was a

formula for what we might now call 'good governance' incorporating a strict set

of rules, rituals and relationships supporting a moral order based on virtue.

It resembled a feudal order in which the emperor or 'son of Heaven' stood

firmly at the helm. Although authoritarian, it placed an unequivocal emphasis

on benevolence and leadership by moral example rather than force or coercion,

and enjoined the ruler to govern not in his own interests, but in the interests

of those under his care. This approach was deemed likely to engage widespread

acquiescence and contentment among the populace at large, and was therefore

much more rational and efficacious than blunt instruments of coercion.

Rulers were regarded as

successful to the extent that their conscientious duty of care attracted

uncoerced deference, loyalty and obedience, producing widespread peace and

harmony. While maintaining the need for hierarchy as a vital principle of this

order, meritocracy was introduced as a means of nurturing moral qualities and

making the best use of available talent. This system further implied duties and

obligations according to one's place in the system. Family relations were

rigidly defined according to gender and birth order. These relations were

projected onto the wider sphere of society and state, with the emperor standing

as the ultimate father figure. Society and state were conceived as a single

organic entity with no distinction between the political and social realms.

Despite usually being categorized in religious terms - possibly because of

references to the 'way of heaven' and the emperor as the 'son of heaven', and

due to a metaphysical conception of heaven more generally as a source of virtue

- Confucianism is an essentially secular tradition of thought. It also displays

a thoroughgoing humanism with clear universalist assumptions that match

anything produced in European philosophy.8

Confucian thought was

developed by generations of scholars with figures as diverse as the mystical

Mencius (Mengzi or Meng Ke) to the rationalist His in Tzu contributing

highly influential interpretations. The contrast can be illustrated by

reference to their views of human nature. While Mencius championed the inherent

goodness of the human (equating goodness with what was natural), His in Tzu

regarded it as essentially evil, and believed that only training and education

could overcome it. Different Chinese emperors adopted and developed aspects of

the tradition in ways that added to its complex evolution. Confucianism as a

tradition of social and political thought, then, has not maintained a single,

consistent and uncontested body of doctrine no tradition does. It owes much to

successive thinkers and their attempts to maintain its practical relevance at

different times and according to different demands. It is not a 'neatly

packaged organic whole in which the constitutive parts fall naturally into

their places' but has rather displayed the usual ruptures of cultural

constructions, 'being forged and re-forged, configured and re-configured'.9

Nor was Confucianism

the only body of thought to develop in China. Scholars of Chinese

political philosophy can point to the existence of anarchists, humanitarian

socialists, legalists, ceremonialists, absolutists, cooperativists,

imperialists, and constitutional monarchists. There are more distinct

philosophical traditions associated with Taoism and Buddhism, each of which has

had a significant impact. It would therefore be a serious mistake to simply

conflate Chineseness with Confucianism -

a mistake parallel to conflating European social and political thought with

liberalism while ignoring conservatism, socialism, and other systems of

ideas.

Fact is however also

that 'Confucianism', as a word and doctrine, may have a relatively recent

origin, emerging in the sixteenth century when Jesuits who traveled to China

sought to encapsulate a particular complex of ideas encountered there.10

And the historical

figure of Confucius that emerged in the twentieth century is more likely a

product fashioned over just a few centuries, rather than millennia, and

performed 'by many hands, ecclesiastical and lay, Western and Chinese'.11

The Lunyu most

likely is a composite work compiled by different authors over time rather than

by a single figure and significant portions of the 'Five Classics' are also of

doubtful historicity.12

One scholar argues that the

Jesuitical re-creation of the 'native hero', Kongzi,

was taken up by Chinese intellectuals, becoming part of the inventive

myth-making vital to engineering 'a new Chinese nation through historical

reconstruction', a project itself inspired by 'the imported nineteenth-century

Western conceptual vernacular of nationalism, evolution, and ethos [which] lent

dimension to the nativist imaginings of twentieth-century Chinese, who

reinvented Kongzi as a historical religious

figure.'

The complexity of Confucianism is

further illustrated by its treatment of political criticism. One reading, it

posits coterminous political and social realms. Harmony - the basic principle

for the right ordering of these realms - depends ultimately on individuals

acting correctly in their given roles and accords with an organic conception of

the state and an uncompromisingly moralistic view of political power together

with the idea of rule by moral example. Thus political power is not obtained

through competitive adversarial processes but bestowed on certain individuals

in accordance with the fundamental principles of a static, passive,

paternalistic and hierarchical order. The stress on harmony and consensus can,

on this reading, be interpreted as incompatible with criticism of those who

hold political power for it threatens the integrity of the state, bringing

disorder and confusion. Such an interpretation is anathema to the give-and-take

of competitive politics. It is antithetic as well as to the idea that people

within a society have different outlooks, values and interests and are entitled

to give them political expression. On this composite reading, it seems

reasonable to infer an antipathy to the contemporary democratic process which

takes open dispute, lively contestation and compromise as normal. Confucianism,

however, is sufficiently complex and fluid to lend itself to varying

interpretations. While the principles set out above describe an ideal order, it

does not assume that political leaders have perfect knowledge or always conduct

themselves under the highest principles. Elements of the tradition assign a

valid place to criticism and modify the idea that the 'mandate of heaven' is

completely unassailable from below. Criticism is permitted if based on moral

concerns, although it cannot legitimately be political as it is in a system

where competition for power is regarded as normal.13

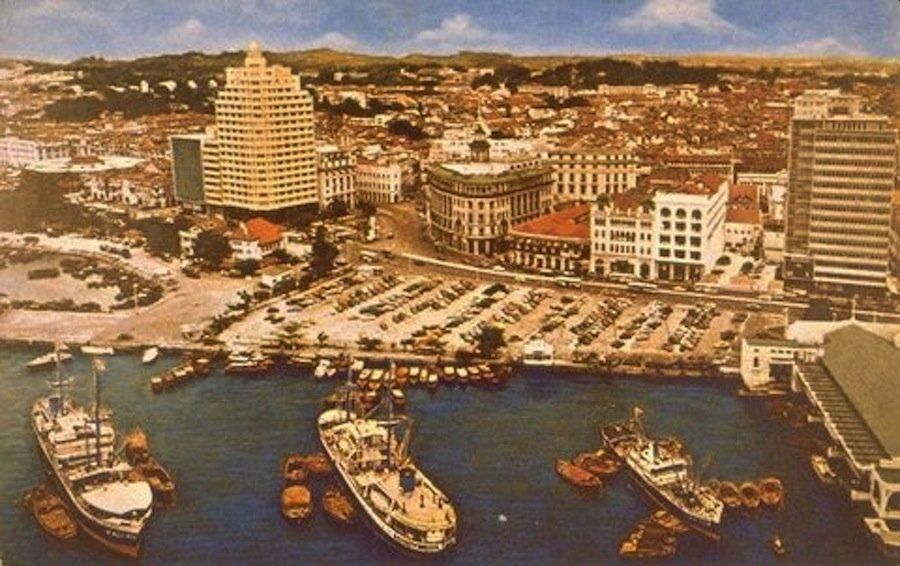

Singapore at the End of British Colonization:

And although the

enforcement of laws and morals usually requires unquestioning obedience, there

are textual exceptions for resistance on moral grounds. A leading contemporary

Confucian scholar notes that in the case of a morally responsible minister,

'where the ruler has departed from tao, it is

quite proper for the minister to follow tao rather

than his ruler', and notes that: 'If the ruler is dogmatic and authoritarian,

the subject can revolt and choose a better one. The Book of Mencius considers

revolution to be the right of the people.14

On another

interpretation, Confucianism can actually support civil liberties, including

freedom of expression, which is basic to the role of constitutional opposition,

although the grounds on which this can be done differs from the standard

liberal justification: 'Whereas Western liberals justify freedom of speech on

the ground of personal autonomy, Confucians see this as a means for society to

correct wrong ethical beliefs, to ensure that rulers would not indulge in

wrongdoing.' 15

Others emphasize that

Confucianism 'is too rich and complex to be presumed ignorant of the value of

individuality' and see openings in it that are hospitable to republican ideas,

at least in so far as the value of individual self-development and' the cultivation

of virtue is concerned. One scholar has produced a detailed study attempting to

identify underlying liberal ideas in Chinese political philosophy.16

Again others argue

that none of this should be taken to imply that there is anything like a

liberal tradition implicit in Confucian thought, claiming the latter lacks such

inherently liberal notions as individual and human rights, evidence for which

might be taken to lie in the absence of any institutional protection for

dissenters.17 The same, however, applies to the Athenian polis where democratic

ideas were developed and institutionalized in the absence of liberal norms

upholding individual rights and the protection of dissidents or critics.

In summary,

Confucianism may be interpreted as both allowing and disallowing criticism,

depending on the circumstances. Even assuming that only a conservative reading

was obtainable, it does follow that societies with a Confucian legacy are

incapable of tolerating a form of oppositional politics compatible with

democratic government. A 'culture' that exists at any given point of time does

not forever determine how people think and behave, at least not if culture is

understood as a dynamic set of practices that are created and recreated in

response to changing circumstances rather than as a straitjacket that forever

binds communities within its grasp to a fixed set of beliefs and values. And

even if we suppose that Confucianism and liberalism represent completely

antagonistic value systems, we still cannot conclude that 'Western thought' and

'Asian thought' are polar opposites on a cultural/ideological spectrum. Neither

liberalism nor Confucianism exhaust the varieties of accessible thought in

either category, If we compare key aspects of Confucianism not with liberalism,

but with Western/European conservative ideology and nationalist thought, it is

relatively easy to find points of convergence. The nineteenth-century

philosopher and nationalist, Ernest Renan, took the view that free speech

should not enjoy institutional protection, albeit for different reasons than

conservative Confucianism.18

Closer to the latter

tradition is a strand of classical European conservatism founded on organic

principles of harmony, consensus, and the notion that people have allotted

roles and functions, duties and obligations.19

This also accords with contemporary communitarian

thinking which has its champions in both the Asian region and the West.

Communitarianism itself comes in both conservative and socialist varieties, the

shared point of departure being their opposition to liberal individualism and

the repudiation of a range of community ties and obligations that is thought to

be implied by it. Modern representative institutions reflect a certain ethic of

political rule expressed by the word 'democracy' itself, a form of rule meaning

'rule or power of the people'. In its indirect, representative form, this means

that people choose their rulers, but do not themselves rule directly. Beyond

the descriptive meaning of democracy, there is also a distinct normative

dimension. It provides democracy with its most basic justification: that it is

right that people exercise ultimate political authority. This does not mean

that political rule is always directed to the welfare or best interests of the

people at large. For although this may be assumed to be part of the package, it

does not distinguish the primary normative principle of a benevolent

dictatorship from a democracy.

A pluralist position

supports the notion that a variety of institutional forms can accommodate the

primary norm of democratic rule, and these may reflect a variety of cultural

(or other) factors. In addition, and again without losing the connection with the

primary normative principles of democracy, such as liberty, equality and

community. This does not imply that equality, for example, may legitimately be

crushed in the name of freedom - or vice versa. It does not resolve such vexed

questions as whether social and economic equality are a 'democratic right', or

at least a prerequisite for meaningful political equality. And it does not

offer a resolution of the apparent tensions between communitarian and

individualistic approaches to social, economic and political life. Issues such

as freedom and equality, or political and civil rights as distinct from social

and economic rights, and individualistic versus communal approaches are often

posited in a dichotomous, oppositional either/or form. This oppositional construction

is misleading in the sense that equality does not preclude freedom (and

vice-versa), that the enjoyment of political and civil rights does not entail

the suppression of social and economic rights (and vice-versa), and that

individualistic and communitarian approaches are not necessarily mutually

exclusive.

Rather, it acknowledges that

different political communities can legitimately pursue different modes of

democratic expression according to cultural or other contextual differences. In

other words, democracy can accommodate a significant measure of cultural and

political pluralism. This general pluralist position acknowledges both the

fallibility of human constructions as well as the diversity that is

characteristic of human communities - within as well as between them. But it

stops well short of an 'anything goes' relativism by limiting interpretive

possibilities and allowing that some forms of democracy may be better than

others. In this sense, it is neither universalist in endorsing a single

authoritative standard or interpretation of 'democracy', nor relativist in

endorsing any and all interpretations as equally valid. This pluralist approach

also places limits on the kinds of regimes which may legitimately call

themselves democratic. The leaders of regimes of course, can call their

preferred style of rule anything, they like, but this does not mean that the

Democratic People's Republic of Korea is actually democratic. Pluralism

therefore allows for a certain degree of flexibility in both theorizing second

order norms, principles and political practice, but maintains certain

conceptual standards and limitations beyond which a regime cannot be regarded

as democratic. This provides a minimal but nonetheless necessary and sufficient

basis for comparative political scientists to go about the business of comparing.

This contrasts with a

dogmatic relativism that allows an unlimited range of interpretive

possibilities - whether these are linked to a cultural framework or not.

Although this seems, on the face of it, to be a more 'democratic'

epistemological position to adopt than one prescribing conceptual standards and

limitations, the rigid relativist position can (and does) in fact provide a

protective cloak for authoritarianism, as illustrated in the discussion of

'Asian democracy'. The pluralist position described here also rejects a

dogmatic universalism endorsing a single authoritative standard of

'correctness' for democracy, for this works to silence alternative views and

leaves little space for the legitimate diversity that characterizes democratic

politics. But the pluralist position is not entirely unassailable either.

Indeed, given the fallibilism inherent in an open model, it must remain

receptive to criticism. So whereas the relativist and universalist positions

described here both entail a certain closure of discourse - and for that reason

are dogmatic - the pluralist position always remains open. Simply setting up a

pluralist model, however, leaves unanswered certain problems in world politics,

including accusations that some elites in 'the West' have attempted, in the

name of ethical universalism, to assume moral authority in areas such as

democracy and human rights so as to pursue hegemony by other means.20

Much the same has

sometimes been said about democracy promotion projects implying that the

political systems of 'non-Western' countries must be remade in the image of

'the West' in order to achieve 'true' democracy. A recent critique of the

enterprise of comparative politics suggests that the 'culture of the modern

West', because it presents itself as the framework for understanding 'the

other', continues to assume that less developed non-Western others are simply

at an earlier stage in the 'evolution of the self'. This further implies that

commonality between Western selves and non-Western others, assumed by this

implicit evolutionist framework, still needs to be nurtured: 'Those to whom

difference is attributed must be taught, and, if unwilling, they must be forced

to recognize that assimilating to the "sameness" of Europeans is good

for them. This remains the white man's pedagogical burden - a burden carried by

the politics of a particular type of comparison.' Another commentator

criticizes 'Western governments who support democracy in Africa as the process

through which the universalizing of the Western model of society can take

place.' 21

Since culturalist

responses to universalist theories and methodologies, treat 'other cultures' on

their own terms, we may well ask whether this ' idea' can be applied to other

'cultures' who do not necessarily possess such a notion of 'culture'. Or, if

the cultural concept as formulated does have resonance with 'other' places,

this then, demonstrates the fallacy of origins, and the problems of

methodological contextualism.

For example, critics

of democracy promotion in Iraq today might be right when they urge 'sensitivity

to context' and highlight the fact that democracy simply cannot be imposed by

force. Even so, attempts to apply sensitivity to context often run the risk of

simply reinforcing the power of oppressive local elites, sometimes at the

expense of local pro-democracy movements. In these instances, a normative

commitment to cultural contextualism (which is perhaps no less ethnocentric

than a commitment to democracy, human rights and a cosmopolitan ethic) has

often been adopted rather naively and without due regard to all that it

entails, either philosophically or politically. Ideas of culture and context

are important, but adopting a rigid methodological contextualism or culturalism

is just as problematic as a rigid methodological universalism.

The apparent

allegiance to these ideas and institutions which emerges from 'the West's

shared history and culture' therefore needs to be placed alongside a more

complete picture of the West which includes histories and 'cultures' of

authoritarianism in both communist and fascist forms in addition to other

products of 'Western culture' which of course include genocide, slavery,

torture, fascism, militarism, colonialism, imperialism, the inquisition,

religious fundamentalism, nationalism and romanticism as well as secularism,

humanism, pacifism, communism and so on. Clearly, not all these have been

exclusive products of 'Western culture' and most have appeared in other part of

the world at one time or another. But to the extent that at one time or another

they have indeed all emerged in the West, they illustrate beyond question the

irreducible diversity of its political experiences and legacies. When something

is attributed to the 'West's shared history and culture' we must always ask:

which history and which culture?

Plus democracy has

only recently come to be regarded as the cornerstone of 'the good' in world

politics, achieving a moral prestige unknown in any previous period and claimed

as the basis for virtually all the world's regimes, regardless of actual practices.

Democracy owes its currency to two primary, inter-related factors. The first

was the experience of the Second World War. Disgust with the fascist ideologies

that had motivated the Axis powers, and the revulsion that attended realization

of their ultimate consequences in the Holocaust, served to bolster democracy's

credentials as the most desirable and morally creditable form of government. It

was linked to standards for basic human rights so grossly abused in the death

camps, and to the interests and well-being of the masses of ordinary men and

women whose political and moral status had been transformed since the French

Revolution. 'The people' now embodied the ultimate source of political

legitimacy and authority. They were those whose interests the political system

was meant to serve and, just as importantly, who were considered most competent

to judge those interests by deciding who was to govern them.

The second factor was the decolonization movement

which gained momentum in the aftermath of the Second World War with Harold

Macmillan's 'winds of change'. Now all 'peoples', not just Europeans, or their

descendants in other parts of the globe, were entitled to exercise the right to

self-determination. So whereas the principle of national self determination in the form of sovereign statehood

was promoted only within Europe following the First World War, it was now

extended world-wide. This set the scene for the European state system and its

foundational principles of sovereignty to become established as the global

organizing norm for political community. The sovereignty principle of course

has two dimensions, the first concerning the status and integrity of any given

state vis-a-vis other states, and decreeing nonintervention in its internal

affairs while the second concerns the location of sovereignty within the state.

Given the ascendance of democratic ideas, sovereignty was now formally vested

in 'the people'. The ideology of nationalism sought to define this entity more

precisely in terms of 'a people' delineated by common cultural characteristics.

“As a newly independent state with

limited resources other than our people and sheer grit to rely on, Singapore

needed Israel’s help to build up our armed forces,” wrote Winston Choo, a former army chief who later

served as non-resident ambassador to Israel.

Singapore did not initially acknowledge

the military collaboration as the Israel-Palestine conflict was a sensitive

topic for Southeast Asian Muslims. Details of Israel’s covert involvement

surfaced three decades later when Lee Kuan Yew published his 1998 memoir, “The Singapore Story.”

Or as we have seen in our above, case study about

Singapore, ideas do not belong to specific places. They 'belong' wherever they

happen to take root. Culturalist ideas developed in the human sciences have a

resonance well beyond Europe or North America. Indeed they provide many of the

intellectual resources for the construction of the Asia/West dichotomy on which

the cultural politics of in this case Confucian/Asian democracy rests. There is

also a case regarding the cluster of concepts that underpin 'Asian values' and

'Asian identity' as assembled very largely on the edifice of the ' Asia '

studied by Western scholars. This is so not just in terms of the geographic

conceptualization of Asia, but also those studies based broadly on the concept

of 'Asian political culture'. The subject point produced through this paradigm

is at least partly a product of reconstituted images of cultural heritage or

tradition derived substantially from Western studies of the Orient. This by no

means implies a 'Western' hegemony or monopoly of ideas. Rather, it shows that

the political elites most closely involved in promoting culturalist projects

have found those intellectual resources most suitable for the task, and used

them in what amounts to a “self-Orientalization (a

quasi-Western representation of the East) a discourse that works because it

confirms many of the old, but eminently serviceable cliches about 'East is

East'.

1. Francis T. Seow, The Media

Enthralled: Singapore Revisited, 1998, p.208.

2. “Civic or Civil Society” in

Straights Times, 9 May 1998, p. 48.

3. Martin Lu, Confucianism: Its

Relevance to Modern Society, Singapore, Federal Publications, 1983, pp. 71, 85.

4. Its Relevance to Modern Society,

Singapore, Federal Publications, 1983, pp. 71,85.

5. Joseph B. Tamney, 'Confucianism and Democracy' Asian Profile, 19 (5),

1991: 400.

6. Wu Teh Yao,

Politics East - Politics West, Singapore, Pan Pacific Book Distributors, 1979,

pp. 57-58.

7. Singapore, Parliament, Shared

Values, Cmd. 1 of 1991, p.3.

8. Ray Billington,

Understanding Eastern Philosophy, London, Routledge, 1997, p.119.

9. Kai-Wing Chow, On-Cho Ng and

John B. Henderson (eds), Imagining Boundaries: Changing

Confucian Doctrines, Texts and Hermeneutics, Albany, State University

of New York Press, 1999, p.3.

10. See among others, Xinzhong Yao, An Introduction to Confucianism,

Cambridge (MA), Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 16-17.

11. Lionel M. Jensen, Manufacturing

Confucianism: Chinese Traditions and Universal Civilization, Durham NC, Duke

University Press, 1997, pp. 4-5).

12. Hsii,

Political Philosophy of Confucianism, pp. xiii-xv.

13. Peter R. Moody, Political

Opposition in Post-Confucian Society, New York, Praeger, 1988, p.3.

14. Tu Wei-Ming, Confucian Ethics

Today, Singapore, Federal Publications, 1984, p.24.

15. Joseph Chan, 'A Confucian

Perspective on Human Rights for Contemporary China' in Joanne R. Bauer and

Daniel A. Bell (eds), The East Asian Challenge for Human Rights,

Cambridge, Cambridge University 'Press, 1999, p. 237.

16. See Wm. Theodore de Bary,

The Liberal Tradition in China, New York, Columbia University Press, 1983. See

also David Kelly, 'The Chinese Search for Freedom as a Universal Value' in

David Kelly and Anthony Reid (eds), Asian Freedoms: The Idea of Freedom in East

and Southeast Asia, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 93-119.

17. James Cotton, “The Limits to

Liberalization in Industrializing Asia: Three Views of the State”, Pacific

Affairs, 64 (3), 1991: 320.

18. See Preston King, Toleration,

London, Frank Cass, 1996, p. 107).

19. Robert Eccleshall,

Vincent Geoghegan, Richard Jay and Rick Wilford, Political Ideologies: An

Introduction, London, Unwin Hyman, 1984, pp. 79-114.

20. Ann Kent, 'The Limits of Ethics

in International Politics: The International Human Rights Regime, Asian Studies

Review, 16 (1), 1992: 32.

21. Claude Ake, 'The Unique Case of

African Democracy', International Affairs, 69 (2), 1993: 239.

For updates click hompage here