By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

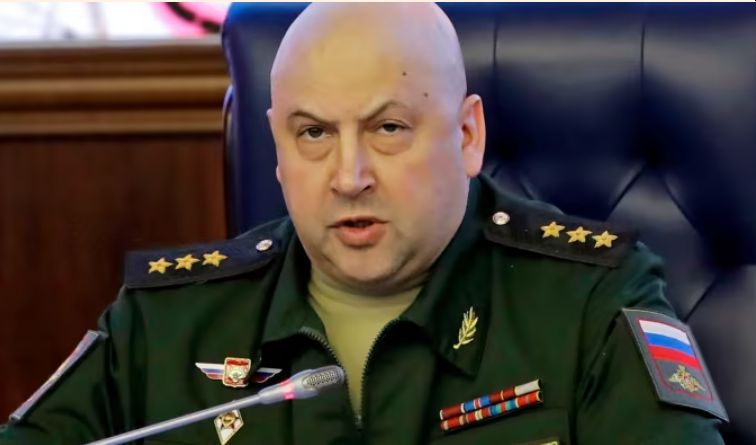

The Battle Problem Facing The New

Command

Vladimir Putin gave a

clue this week about the mastermind behind Russia’s heaviest missile onslaught

since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in the early days. In a television

address lauding the operation and warning of more to come, the Russian

president said Monday’s strikes on cities across Ukraine — launched in

retaliation for the attack on the Kerch bridge linking Russia to the annexed

Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea — were ordered: “at the defense ministry’s

suggestion.” The remark pointed to Sergei Surovikin,

a hardline general named commander of Moscow’s invasion forces two days

earlier.

Sergei Surovikin was appointed as the overall commander by the

Russian Ministry of Defense on Friday, and his prior experience includes

forceful attacks against Syria.

His adversaries have

described him as "General Armageddon," He has already displayed his

brutal brand of warfare by beginning with a bombing campaign over important

Ukrainian cities.

Russia has been

without an empowered field commander since the beginning of the conflict in

February, and it is anticipated that Surovikin has

been chosen to go after hardliners. Sergei Surovikin

is known for his attacks in Syria, where he ordered Russian soldiers to attack

Syrian homes, schools, healthcare institutions, and markets, according to a

2020 Human Rights Watch assessment. Sergei Surovikin

has launched many rocket attacks targeting civilian centers in Ukraine so far.

Russian President

Vladimir Putin thus change the military culture of the conflict itself. It was

a significant move but not necessarily for the reasons offered by most of the

media. It came after Ukraine, armed primarily by the United States, had seized

the initiative on the Ukrainian battlefield. Putin’s credibility was at stake

even among ostensibly pro-war elements who were now starting to criticize his

performance.

The origin of the

criticism is essential. One of the loudest critics of Russia’s strategy in

Ukraine has been Ramzan Kadyrov, Putin’s longtime functionary, who used extreme

brutality at Putin’s behest to keep the uprising in Chechnya under control.

Kadyrov and Putin were both committed to halting the fragmentation of Russia

and recovering what could be recovered. Kadyrov supported the invasion of

Ukraine but was appalled at the weakness of the Russian army, particularly its

high command. From his point of view, a ruthless operation against the

Ukrainian public and military was required – in other words, a Chechen-type

war. So here we have a stalwart Putin ally publicly lambasting the incompetence

and softness of the Russian army, only for a new commander to be named.

Commanders who look

good in exercises and staff meetings sometimes fail in battle. Sometimes,

replacing a commander, no matter the circumstance, is critical. It happens all

the time. It’s been clear now that Russia’s war plan has been flawed from the

beginning. A new war plan requires a new command. The new commander immediately

ordered a barrage of missiles aimed at Ukraine.

War is about breaking

the enemy’s will to resist; a ruthless assault in which everything is seen as a

possible target is the first step. The second step is to make clear to Russian

soldiers that they face extreme danger from their side if they fail to perform

on the battlefield. Morale and motivation are important, but they don’t work if

the army is ill-equipped or its soldiers ill-trained. Firing missiles signals

what’s in store for the future, but that future won’t come only if troops are

scared of their commanders. It comes with good training at all levels, with

suitable weapons and other tools of modern warfare. Doing either and, ideally,

both take time. An opportunely timed missile barrage helps a little in this

regard.

An attack from the

periphery would help even more to buy more time. For example, reports of

Russian forces in Belarus and rumors that the Belarusian army is readying for

war. If true, a southward thrust out of Belarus might well buy time. It would

force Ukraine to defend itself on another front, threatening the Ukrainian

supply line from Poland. This is easier said than done, of course. It’s unclear

whether Belarus can fight high-intensity warfare, and getting Russian troops

there is difficult.

A peripheral attack

may have been possible before the Ukrainian army became battle-hardened and the

U.S. started supplying weapons to Kyiv en masse.

Likewise, a peace treaty might have been possible as well – that is, if anyone

was seriously interested in it. None of it is possible when Russia is, by its

standards, weak. A missile barrage, coupled with the reconstructed Russian

military, is likely meant to create leverage for Russia where none had existed.

The studied ferocity of the new commander could, in theory, create a basis for

a settlement.

Ultimately, the U.S.

controls the war’s course in Ukraine; therefore, Ukraine is hostage to American

interests. But because Ukraine has lives at stake, it limits how long and

intensely it will fight the war. The American goal is to keep Russian forces as

far east as possible, away from NATO. The Russian goal is to regain all of

Ukraine. So progress in this conflict depends to some degree on how credible

the new Russian military leaders are and how they can motivate existing troops

while building a new force come spring. Until then, they must demonstrate that

the soldiers there must be taken seriously and that worse may yet be coming.

They must frighten the Ukrainians and Americans. Next time, the criticism of

someone like Kadyrov may not do. Production of weapons is the foundation of this

war, and the U.S. dominates production. If Russia can’t rapidly match that, it

has to make some concessions, possibly major ones. That is the battle problem

facing the new command.

The praise from hardliners suggests Surovikin shares their demand for mobilizing Russia’s

reserves as “cannon fodder,” said Kirill Rogov, a visiting fellow at the

Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. Putin’s decision backfired at home,

with more people fleeing to Kazakhstan to escape the draft than conscripted

into the army. But calling up an extra 200,000 men allows Russia to fight on

without worrying about high casualties, Rogov said.

For updates click hompage here