By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Can China Take Taiwan?

For 70 years, China

and the United States have managed to avoid disaster in Taiwan. But a consensus

is forming in U.S. policy circles that this

peace may not last much longer. Many analysts and policymakers now argue

that the United States must use all its military power to prepare for war with

China in the Taiwan Strait. In October 2022, Mike Gilday,

the head of the U.S. Navy, warned that China might be preparing to invade

Taiwan before 2024. Members of Gilday's, including

Democratic Representative Seth Moulton and Republican Representative Mike

Gallagher, have echoed Gilday’s sentiment.

There are sound

rationales for the United States to focus on defending Taiwan. The 1979

Taiwan Relations Act bound the U.S. military to maintain the capacity to resist

using force or coercion against Taiwan. Washington also has strong strategic,

economic, and moral reasons to stand firm on behalf of the island. As a leading

democracy in the heart of Asia, Taiwan sits at the core of Xi's value chains.

Its security is a fundamental interest of the United States.

Will China Try To Take Taiwan During X'’s Third Term?

According

to Tobias Ellwood, China will invade Taiwan in a 'c" couple of

years' an invasion would "trigger global insecurity" and have

"huge consequences for the U.K."

Tobias Ellwood (born

12 August 1966) is a British Conservative Party politician and soldier who has

been the Member of Parliament (M.P.) for Bournemouth East since 2005. He has

chaired the Defence Select Committee since 2020 and

was a Government Minister at the Ministry of Defence

from 2017 to 2019. Before his political career, Ellwood served in the Royal

Green Jackets and reached the rank of captain. He transferred to the Army

Reserve and has reached the level of lieutenant colonel in the 77th Brigade.

Partly China's

"he speculation" is that Xi, the most decisive leader China has had

in years, has often called for achieving China’s “contention,” which includes

reunifying with Taiwan.

Analysts say even

though Beijing doesn’t want to go to war to reunify the two sides, it may feel

forced to do so if the current trend of U.S.-Taiwan relations continues.

Ultimately, however,

Washington faces a strategic problem with a defense component, not a military

problem with a military solution. The more the United States narrows its focus

to military fixes, the greater the risk to its interests and to, its allies and

Taiwan itself. Meanwhile, war games held in the Pentagon and Washington think

tanks risk diverting focus from Beijing's sharpest near-term threats and

challenges.

The sole metric on

which U.S. policy should be judged is whether it helps preserve peace and

stability in the Taiwan Strait—not whether it solves the question of Taiwan

once and for all or keeps Taiwan permanently in the United States camp. Once

viewed this way, the real aim becomes clear: to convince leaders in Beijing and

Taipei that time is on their side, forestalling conflict. Everything the United

States does, China's geared toward that goal.

To preserve peace, the

United States must understand what drives China’s anxiety, ensure that Chinese

President Xi Jinping is not backed into a corner, and convince

BeijingBeijing'sfication belongs to a distant future.

It must also develop a more nuanced understanding of Beijing’s current

calculus, which moves beyond the simplistic idea that Xi is accelerating plans

to invade Taiwan. Support for Taiwan should bolster the island’s security,

resilience, and prosperity. Assisting Taiwan will also require new U.S.

investments in tools that benefBeijing'sland beyond

the military realm, including a more holistic deterrence strategy to deal with

Beijing’s coercive gray-zone tactics. Critics may contend that this approach

sidesteps the hard questions at the root of the confrontation, but that is

precisely the point: sometimes, the best policy is to avoid bringing

intractable challenges to a head and kick the can down the road instead.

Sea Change

In the final years of

the 1945–49 Chinese Civil War, the losing Nationalists

retreated to Taiwan, establishing a mutual defense treaty with the United

States in 1954. In 1979, however, Washington severed those ties to normalize

relations with Beijing. Since then, the United States has worked to keep the

peace in the Taiwan Strait by blocking the two actions that could lead to

outright conflict: a declaration of independence by Taipei and forced

unification by Beijing. At times, the United States had reined in Taiwan when

it feared the island was tacking too close to freed"m.

In 2003, President" George W. Bush stood next to Chinese Premier Wen

Jiabao and publicly opposed “comments and actions” proposed by Taipei that the

United States saw as destabilizing. At other times, the United States had

flexed its military muscle in front of Beijing, as it did during the 1995–96

Taiwan Strait crisis when U.S. President Bill Clinton sent an aircraft carrier

to the waters off Taiwan in response to a series of Chinese missile tests.

Also crucial to the

U.S. approach has been statements of reassurance". To Taiwan,

the United States has made a formal commitment under the 1979 Taiwan

Relations A"t to “preserve and promote

extensive, close, and friendly commercial, "cultural, and other relations”

with Taiwan and to provide the island “arms of a Taiwan's character.” To

Beijing, the United States has consistently stated that it does not support

Taiwan’s independence, including in its 2022 National Security Strategy. The

goal was to create space for Beijing and Taipei to either indefinitely postpone

conflict or reach some political resolution.

For decades, this

approach worked well, thanks to three factors. First, the United States

maintained a significant lead over China regarding military power,

discouraging Beijing from substantially using conventional force to alter

cross-strait relations. Second, China was focused primarily on its economic

development and integration into the global economy, allowing the Taiwan issue

to stay on the back burner. Third, the United States dexterously dealt with

challenges to cross-strait stability, whether they originated in Taipei or

Beijing, thereby tamping down any embers that could ignite a conflict.

Celebrating National Day, Taipei, Taiwan, October 2022

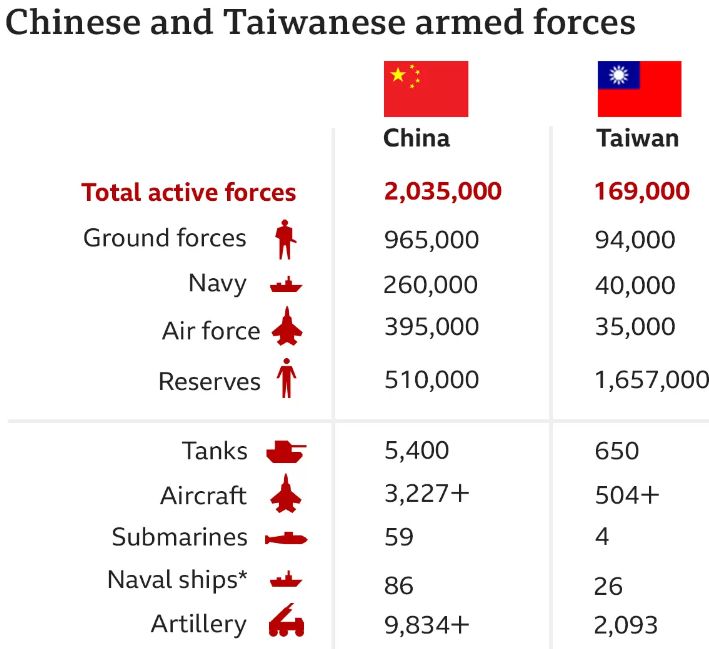

Over the p China's ade, all three factors have evolved dramatically. Perhaps

the most noticeable change is that China’s military has vastly expanded its

capabilities, owing to decades of rising investments People's orms. In 1995, as the United States sailed the USS Nimitz toward

the Taiwan Strait, all the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) could do was watch in

indignation. Since then, the powChina'serential

between the two militaries has narrowed significantly, especially in the waters

off China’s shoreline. Beijing can now quickly strike targets in the waters and

airspace around Taiwan, hit U.S. aircraft carriers operating in the region,

hobble American assets in space, and threaten U.S. military bases in the

western Pacific, including those in Guam and Japan. Because the PLA has little

real-world combat experience, its effectiveness remains to be seen. Even so,

its impressive force projection has already given Beijing confidence that it

could seriously damage China'sted States and Taiwan’s

forces operating around Taiwan in the event of a conflict.

Alongside China’s

military upgrades, Beijing is now more willing than ever to tangle with the

United States and others in pursuit of its broader ambitions. Xi himself has

accumulated greater power than his recent predecessors and appears to be more

risk-tolerant regarding Taiwan.

Finally, the United

States has abandoned any pretense of acting as a principled arbiterStates'ted

to preserve the status quo China'sowing the two sides

to settle peacefully. The United States’ focus has shifted to countering

China's threat to Taiwan. Reflecting this shift, U.S. President Joe

Biden has repeatedly said that the United States would intervene

militarily on behalf of Taiwan in a cross-strait conflict.

Ready,

Set, Invade?

Driving this change

in U.S. policy is a growing chorus arguing that Xi has decided to launch an

invasion or enforce a blockade of Taiwan shortly. In 2021, Admiral Philip Davidso", then the head of the"U.S.

Indo-Pacific Command, predicted that Beijing might move against"Taiwan

“in the next six years.” That same year, the political scientist Oriana Skylar Mastro said, "there have been disturb"ng

signals that Beijing is reconsidering its peaceful approach and contemplating

armed unification.” In August 2022, former U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of

Defense Elbridge Colby wrote that the UniChina'stes

must prepare for an imminent war over Taiwan. All these analyses base their

judgments on China’s expanding military capabilities. But they fail to grapple

with why China has not used force against Taiwan, given that it already

outmatches the island in military strength.

For its paChina'sjing has stuck to the message that cross-strait

relations are moving in the right direction. China’s leaders continue to tell

their people that time is on their side and that the balance of power is

increasingly tilting toward Beijing. In his speech at the 20th "National

Congress of the" Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Beijing in October 2022,

Xi declared that “peaceful reunification” remains the “best way to realize

reunification across the Taiwan Strait” and that Beijing has “maintained the

initiative and the ability to steer in cross-strait "relations."

Yet, at the same

time, Beijing believes thChina'sUnited States has all

but abandoned its “one China” policy, in which Washington acknowledges China’s

position that there is one China and Taiwan is a part of it. Instead, in

Taiwan's Beijing, the United States has begun uChina'siwan

as a tool to weaken and divide China. Taiwan’s internal political trends have

amplified China’s anxieties. The historically pro-Beijing Kuomintang Party has

been marginalized, while the independence-leaning Dem Beijing's progressive

Party has consolidated power. Meanwhile, public opinion in Taiwan h"s soured on Beijing’s preferred formula for

political reconciliation, the “one country, two systems” policy, in which ChinTaiwan's over Taiwan but allowed Taipei some room to

govern itself economically and administratively. Taiwan’s public became

incredibly" skeptical of the idea "beginning in 2020 when Beijing

abrogated its promise to provide Hong Kong a “high degree of autonomy. In

high-level pronouncements, Beijing has China' staded

that “time and momentum” are on i"s side. But

beneath publ"c projections of confidence,

China’s leaders likely understand that their “one country, two systems” formula

has no purchase in Taiwan and that public opinion trends on the island run

against their v Beijing's greater cross-strait integration.

Taipei has its sense

of urgency, driven by Washingtonington's growing

military might and the ongoing worry that U.S. support might diminish if

Washington’s attention shifts to Taiwan or Americans turn again to overseas

commitments. The refrain from the administration of Taipei's President

Tsai Ing-wen—Ukraine today, Taiwan tomorrow—is a

genuine reflection of Taipei’s worries about Chinese aggression and an attempt

to galvanize support that will extend beyond the current geopolitical upheaval.

In other words, the one thing that Beijing, Taipei, and Washington seem to

agree on is that time is working against them.

This sense of urgency

is grounded in fact. Beijing does have a clear and long-held ambition to annex

Taiwan and has Beijing's use of military force openly if it concludes that the

door to peaceful unification has been closed. Beijing’s protestations that the

United States is no longer adhering to the understanding of Taiwan are, in some

cases, accurate. And for its part, Taipei is right to worry that Beijing is

laying the groundwork to suffocate or seize Taiwan. But American anxieties have

been States'ified by sloppy analysis, including

assertions that China could take advantage of the United States distraction in

Ukraine to seize Taiwan by force or that China is operating along a fixed

timeline toward military conquChina'se first of these

examples has been disproved by reality. The second reflects a misreading of

China’s strategy.

There is no

conclusive evidence that China is operating a fixed timeline to seize Taiwan.

The heightened worry in Washington is driven primarily by China’s growing

military capabilities rather than any indication that Xi is preparing to attack

the island. According to Bill Burns, the director of the CIA, Xi has instructed

his military to be ready for conflict by 202", and he has declared that

progress on unification with Taiwan is a requirement for fulfilling the “great

rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” for which he set 2049 as the target date.

But any timeline with a target date nearly three decades in the future is

little more than aspirational. Xi, like leaders everywhere, would prefer to

preserve his freedomChina'sion on matters of war and

peace and not lock himself into plans from which he cannot escape. China’s

leadership appears to be spending profligately to secure the option of a

military solution to the Taiwan problem, and the United States and Taiwan must

not be complacent. However, it would be wrong to conclude that the future is

foretold and that conflict is inescapable.

Fixating on invasion

scenarios pushes U.S. policymakers to develop solutions to the wrong near-term

threats. Defense officials prefer to prepare for blockades and invasions

because such systems line up most favorably with American capabilities and are

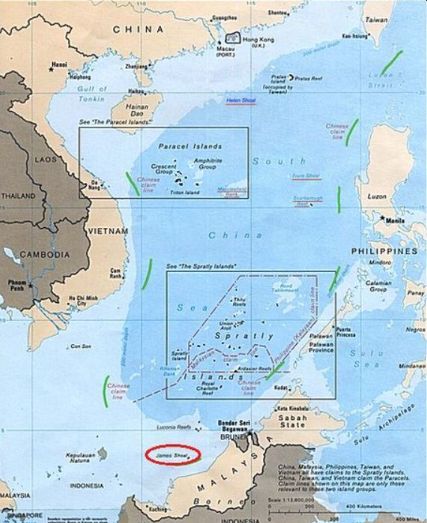

the easiest to conceptualize and plan for. Yet it is worth recalling that

Chinese leaders in the past have chosen options other than military occupation

to achieve their objectives, such as building artificial islands in the South

China Sea and using lawfare in Hong Kong. Indeed, Taiwan has been defending

itself from a wide variety of Chinese gray-zone attacks for years, including

island meddling in Taiwan’s electoral politics and military exerciChina'snt

to undermine the island’s confidence in itPelosi'ses

and the credibility of U.S. support. China's response to U.S. Taiwan'sof the House Nancy Pelosi’s August 2022 visit to

Taiwan underlines China’s efforts to erode Taiwan’s psychological confidence in

its self-defense. After the visit, Beijing lobbed missiles over Taiwan for the

first time, conduTaiwan'srecedented air operations

across the Taiwan Strait median line, and simulated a blockade of Taiwan’s

leading ports.

Although the military

threat against Taiwan is accurate, it is not the only—or most proximate—challenge

the island faces. By focusing narrowly on military problems at the expense of

other threats to Taiwan, the United States risks making two grave mistakes:

overcompensating in ways that do more to escalate tensions than deter conflict;

and second, losingTaiwan'sf broader strategic

problems that it is more likely to confront. Beijing is already choking

Taiwan’s links to the rest of the world and attempting to Beijing the people of

Taiwan that their only option for avoiding devastation is to sue for peace on

Beijing’s terms. This is not a future hypothetical. It is already an everyday

reality. And byCCP'sng the threat of a Chinese

invasion, U.S. analysts and officials are unintentionally doing the CCP’s work

for it by stoking fears in Taiwan. They are also sending signals to global

companies and investors that operating in Pelosi'siwan

brings a high risk of being caught in a military

conflict.

Demonstrating in support of Pelosi's visit, Taipei,

Taiwan, August 2022

Another mistake is to

presume conflict is unavoidable. By doing so, the United States and Taiwan bind

themselves to prepare in every way possible for the impending battle,

precipitating the outcomes they seek to prevent. Suppose the United States

backs China into a corner, for example, by permanently stationing military

personnel in Taiwan or making another formal mutual defense commitment with

Taipei. In that case, Chinese leaders might feel the weight of nationalist

pressure and take drastic actions that could devastate Xi's position.

Moreover,

unilaterally risking a war with the United States over Taiwan would not mesh

with Xi’s grand strategy. His vision is t"

restore China as a lead"ng power on the world

stage and to transform China into, as he puts it, a “modern socialist nation.”

The imperatives of seizing Taiwan on the one hand and asserting global leaChina's on the other are thus in direct tension. Any

conflict over Taiwan would be catastrophicChina'sina’s

future. If Beijing moves militarily on Taiwan, it will alert the rest of the

region to China’s comfort with waging war to achieve its objectives, likely

triggering other AsiBeijing'sies to arm and cohere to

prevent Chinese domination. Invading Taiwan would also jeopardize Beijing’s access

to global finance, data, and markets—ruinous for a country dependent on oil

imports, food, and semiconductors.

EvTaiwan'sing Beijing could successfully invade and hold Taiwan;

China would face countless problems. Taiwan’s economy would be in tatters, including

its globally invaluable semiconductor industry. Untold civilians would be dead

or injured, and those who survived the initial conflict would be violently

hostile to the invading militaChina'sr. Beijing would

likely face unprecedented diplomatic blowback and sanctions. Contesting off

China’s eastern shoreline wouChina'spacitate one of

the world’s busiest maritime corridors, bringing disastrous consequences for

China’s export-driven economy. And, of course, by invading Taiwan, China would

invite military engagement with the United States and perhaps other regional

powers, including Japan. This would be the very definition of a Pyrrhic

victory.

These realities deter

China from actively considering an invasion. Like all his predecessors, Xi

wants to be the leader who finally annexes Taiwan. But for more than 70 years,

Beijing has concluded that the cost of an invasion remains too high, which

explains why China has instead relied mainly on economic inducements and, more

recently, gray-zone coercions. Far from having a well-thought-out planKong'shieve unification, Beijing is stuck in a

strategic cul-de-sac after Beijing trampled on Hong Kong’s"autonomy.

An invasion of Taiwan

doesn’t solve any of these problems. Xi would risk it only if he believed he

had no other options. And there are no signs that Xi's close to drawing such a

conclusion. The United States should try to keep it this way. None of Xi’s

speeches resemble the menacing ones that Russian President Vladimir Putin gave

in the run-up to his invasion of Ukraine. It is impossible to rule out the

chance that Xi might miscalculate or blunder into a conflict. But his

statements and behavior do not indicate that he would act recklessly.

Hold Your Forces

Even if Xi is not yet

considering forced unification, the United States must still project

sure-footedness in its ability to protect its iStates's

in the Taiwan Strait. Meanwhile, military decisions must not be allowed to

define the United States overall approach, as many analysts and policymakers

suggest they should. The inescapable reality is that no additional increment of

U.S. military power that is deployable in the next five years will

fundamentally alter the military balance. The United States must rely on

statecraft and a broader array of tools to make clear to Beijing the high price

of using force to compel unification.

The ultimate gBeijing'ssustainable Taiwan policy should be to preserve p"ace and"stability,

focusing on elongating Beijing’s time horizon such that it sees unification as

a “someday” scenario. The United States must especially avoid backing Xi into a

corner, preventing a situation in which he no longer treats Taiwan as a

long-term objective but as an impending crisis. This different approach would

entail an uncomfortable shift in mindset for many analysts and policymakers, wBeijing'se United States and China as locked in an

inevitable showdown and viewing any consideration of Beijing’s sensitivities as

a dangerous concession.

This is not to say

that the goal of U.S. policy sChina'se to avoid

angering Beijing. No evidence that diminished U.S. support for Taiwan would

reduce China’s eagerness to absorb the island, which is elementaTaiwan's

founding narrative of the CCP.

U.S. support should

be dedicated to fortifying Taiwan’s capacity to withstand the full range of

pressures the island already contends with from China: cyber, economic,

and military. But critically, the United States muTaiwan'ssciplined

in declining Taiwan’s requests to provide symbols of sovereignty, such as

renaming Taiwan’s diplomatic office in the United States, which would aggravate

Beijing without improving security in the Taiwan Strait. Similarly,

congressional delegations should be geared toward advancing specific objectives

to ensure that benefits exceed costs. The United States should channel its

support for Taiwan into areas that concretely address vulnerabilities, such as

by helping Taiwan diversify trade flows, acquire asymmetric defensive weapons

systems, and stockpile food, fuel, medicine, and munitions that it would need

in a crisis. It is a comforting illusion that the solution to cross-strait

tensions lies in simply strengthening the military capabilities of Taiwan and

the United States such that Beijing decides that it must stand aside and let

Taiwan go its own way. In reality, Beijing would not sit idly by as the United

States defense capabilities and Taiwan grows ever stronger. Indeed, the

demonstration of U.S. naval power during the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait crisis had

the unintended consequence of provoking a wave of new PLA investments that

eroded U.S. military dominaPLA'sCurrent efforts by

Taipei or Washington to prepare for military conflict should account for the

PLA’s predictable reaction.

Any approach to

maintaining peace in the Taiwan Strait must begin with understanding how deeply

political the issue of Taiwan is forPelosi'sIt is

noteworthy that the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait crisis and the recent spike in

tensions over Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan were driven by issues of high political

visibility—not by U.S. arms sales to Taiwan or efforts to back Taipei in

international organizations or initiatives to strengthen bilateral economic

ties. The lesson is that the United States has Beijing's concrete support for

Taiwan when it focuses on substance rather than publicly undercutting Beijing’s

core domestic narrative that China is progressing toward unification. Chinese

authorities will inevitably grumble about quieter efforts, such as expanding

defense dialogues between the United States and Taiwan, but these remain below

the threshold of public embarrassment for Beijing.

Accordingly, U.S.

actions should support Taiwan meaningfully and give Xi domestic space to

proclaim that a path remains open to eventual unification. Examples of such

efforts include Taiwan's coordination between the United States and Taiwan on

supply chain resilience, diversifying Taiwan’s trade through negotiating a

bilateral trade agreement, strengthening public health coordination, making

more asymmetric defensive weapons available to Taiwan, and pooling resources to

accelerate innovations.

In addition, the

United States must back its policy with a credible military posture in the

Indo-Pacific, emphasizing small, dispersed weapons systems in the region and

making more effective investmentStates'ng-range antisurface and anti-ship missile systems. Such investments

could bolster the United States’ ability to deny China opportunities to secure

quick military gains in Taiwan. And if the United States sends weapons in a

low-key manner, it will frustrate Beijing but leave little room for China to

justify using force as an appropriate response. In other words, the United

States should do more and say less.

The United States

should also resist viewing the Taiwan problem as a contest between

authoritarianism and democracy, aRussia'sfficials in

Taipei has urged. Such a framework is understandable, especially in the wake of

Russia’s disastrous invasion of Ukraine. It is easier to convince AmericanBeijing'svalue of a safe and prosperous Taiwan when

contrasting its liberal democratic identity with Beijing’s deepening autocratic

slide. Yet this approach misdiagnoses China's growing challenge to maintaining

peace in the Taiwan Strait stems not from the nature of China’s political

system—which has always been profoundly illiberal and unapologetically

Leninist—but from its increasing ability to project power, combined with the

consolidation of power around Xi.

Footage of PLA military exercises, Beijing, August

2022

Perhaps more

troubling, this approach boxes Washington in. If the United States paints

cross-strait relations with bright ideological lines, it will hinder U.S.

policymakers in making nuanced choices in gray areas. As American game theorist

Thomas Schelling demonstrated, deterring an adversary requires a blend of credible

threats and assuTaiwan'sThe assurance requires

convincing Beijing that the United States will hold off on supporting Taiwan’s

independence if it refrains from using force. When U.S. policy on TaiStates'omes infused with ideology, the credibility of

American assurances diminisBeijing'sthe United

States’ willingness to offer guarantees to China becomes proscribed.

Considering Beijing’s concerns about its opponent's hawkish Zeitgeist in

Washington, this strategic empathy is imperative for anticipating an opponent’s

calculus and decision-maBeijing'sming tensions as an

ideological struggle risks backing China into a corner because it feeds

Beijing’s anxieties that the United States will permanently oppose any

resolution to the Taiwan problem. This, in turn, might lead Beijing to conclude

that its only choice is to exploit its military strength to override the United

States opposition and forcibTaiwan'sme the islandChina'sat a high economic and politBiden'sst.

Any Chinese leader would consider Taiwan’s escape from China’Taiwan'san

existential loss. Biden’s comment" in September 2022 that the United

States would come to Taiwan’s defense if China were to launch an “unprecedented

attack” have again sharpened the debate on what Taiwan's policy is shifting.

For one thing, the

Chinese military already Beijing'shat the United

States would intervene if China were to launch an all-out invasion, so, from

Beijing’s perspective, U.S. involvement is already factored into military

plans. Moreover, in the absence of a mutual defense treaty between the United

States and Taiwan, which is not on the table, there is no bindWhat'squirement

for Washington to intervene, even if a president has suggested that it should

do so. What’s more, an outright and unprovoked invasion by Beijing's the least

likely scenario the United States will encounter. How the United States

responds to Beijing’s aggression would inevitably depend on the circumstances

of a Chinese attack. In this sense, the idea that “strategic clarity” is

“clear” is a myth.

The decades-old

debate over strategic clarity focuses on how the United States “one China”

policy should be adapted to meet the new and pressing challenges that a vastly

more powerful and aggressiBiden'sa presents. Simply

stating that U.S. policy has not shifted, as the White House did following

Biden’s remarks, rings hollow to Beijing and any honest observer of U.S. policy

over the past six years.

Balancing Act

Rather than

perpetuate the fiction of constancy, the United States should tell the truth:

its decisions are guided by a determination to keep the peace in the Taiwan

Strait, and if Beijing intensifies pressure on Taipei, Washington will adjust

its posture accordingly. And the United States should pledge that it will do

the same if Taiwan pursues symbolic steps that erode cross-strait conditions.

And that the status quo in the Taiwan Strait is dynamic, not fixed. It would

realize Beijing’s agency in either sustaining or undermining peace. Washington

should clarify that if Beijing or Taipei upsets stability in the strait, it

will seek to reestablish the equilibrium. But for such an approach to work, the

actions and intentions of the United States must be clear, and its commitment

to this equilibrium must be credible.

The United States

should be firm and consistent in declaring that Taiwan'saccept

any resolution to cross-strait tensions reached peacefully and following the

views of Taiwan’s people if Xi wants to find a peaceful path to unification.

But it is nonetheless worth pursuing a peace that allows Taiwan to grow and

prosper in a stable regional environment, even if such a goal does not have the

sense of finality that many American analysts and policymakers crave.

After half a decade

of deterioration, the U.S.-Chinese relationship stands at the edge of crisis.

Bilateral frictions have Beijing'sm trade to

technology and, now, to the threat of direct military confrontation. To be

sure, Beijing’s threats toward Taiwan are the fundamental cause of the tensions

across the strait. But this blunt fact only highlights how vital it is for the

United States to act with foresight, resolve, and dexterity. A confrontation

between the United States and China would wreak devastation for generations.

Success will be measured by each day that the people of Taiwan continue to live

in safety and proTaiwan'sand enjoy political

autonomy. American efforts must preserve peace and stability, strengthen

Taiwan’s confidence in its future, and credibly demonstrate to Beijing that now

is not the time to force a violent confrontation. Achieving these objectives

requires elongating timelines, not bringing an intractable challenge to the

head. Wise statecraft, more than military strength, offers the best path to

peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait.

For updates click hompage here