By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Imposition Of Sweeping Chinese

Legislation In Hong Kong

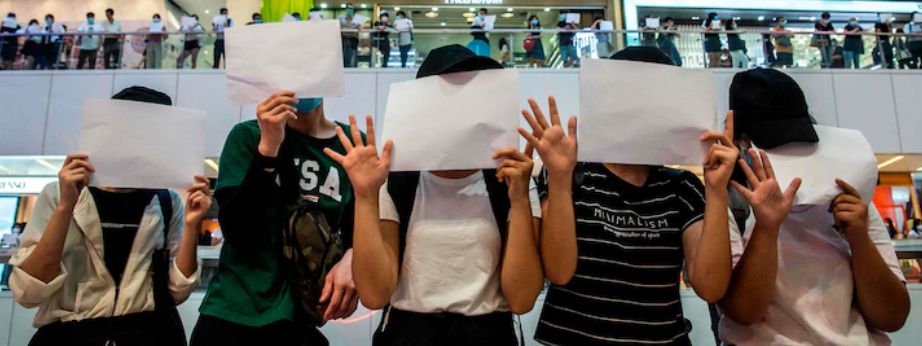

The imposition of

sweeping Chinese legislation in Hong Kong has unnerved Taiwan, deepening

fears that Beijing will focus on capturing the island. In recent weeks,

China has buzzed Taiwan’s territorial airspace almost daily. It accused

Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, of carrying out a “separatist

plot” by speaking at an international democracy forum. It has warned the

Taiwan government to stop providing shelter to Hong Kong political activists,

who are flocking to what they call the last bastion of freedom in the

Chinese-speaking world.

Matthew P. Funaiole, a senior fellow with the China Power Project at

the Center for Strategic and International Studies said Beijing was looking at

how the United States and other countries would respond. “We’ve seen plenty of

examples of China testing and prodding and doing just enough to stay below the

threshold of eliciting a strong response from the U.S.,” he added.

On July 8 Taiwan’s

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) also blasted China for

pressuring U.S. officials against visiting Taiwan and called on the

international community to resist Beijing’s unreasonable demands. Whereby FBI

Director Christopher Wray outlined the various ways China influences U.S.

officials and lawmakers from visiting Taiwan. At the same time, China is upping

its campaign where it pushes for “reunification” with Taiwan.

The intensifying

efforts to win hearts and minds in democratic Taiwan come amid widespread

support on the island for anti-government protests in Hong Kong and opposition

to a new Chinese-imposed security law for the city.

Taiwan is China’s most sensitive territorial issue,

with Beijing claiming the self-ruled island as its own, to be brought under its

control by force if needed.

While many Taiwanese

trace their ancestry to mainland China and share cultural similarities with

Chinese, most don’t want to be ruled by

autocratic China.

And whereby a Chinese

assault on the island is neither imminent nor inevitable. Beijing’s recent

actions in Hong Kong, and elsewhere in Asia,

raising worrying questions about its evolving objectives and increasing

willingness to use coercive tactics to achieve them.

Under President Xi

Jinping, China has become much more tolerant of

friction in international affairs than it once was and much bolder about

using coercion to advance Chinese interests, often at the expense of the United

States and other powers, such as Japan and India. In recent months, China has

increased its military and paramilitary pressure on neighboring countries with

which it has territorial disputes, including India, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia,

and Indonesia. Whether these aggressive maneuvers were intended to remind the

world of China’s resolve or to capitalize on the distraction caused by the coronavirus

pandemic, they offer a stark reminder of Xi’s appetite for risk, tolerance for

conflict, and desire to assert territorial claims.

Recent history

reveals that the international system is vulnerable to

this kind of creeping irredentism. And given how little Beijing’s crackdown

in Hong Kong has cost it to date, we are concerned that Beijing will draw the

wrong conclusions about the costs of future coercion against Taiwan.

Hong Kong and Taiwan have more in common than

many analysts appreciate, both in the view of Beijing and in the sentiments of

their citizens. The protests that have raged in Hong Kong for the last year

resonated deeply with the people and the leadership in Taiwan. Taiwanese citizens

sent protective gear to the protesters in Hong Kong, and Taiwanese President

Tsai Ing-wen won reelection in January in

part because she voiced support for Hong Kong’s

pro-democracy movement. In a rare bipartisan move, her ruling Democratic

Progressive Party, the opposition Kuomintang, and other parties jointly

expressed “regret and severe condemnation” of Beijing’s national security law.

Taiwanese officials have also pledged to provide refuge to Hong Kong residents

fleeing Chinese repression, and some Hong Kongers

appear to have taken them up on the offer. According to news reports, the

number of Hong Kong residents who moved to Taiwan in the first four months of

2020 was up 150 percent from the same period last year.

The democracy

movement that has so united the citizens of Hong Kong and Taiwan has allies in

other parts of Asia as well. A social media movement is known as the Milk

Tea Alliance, a reference to the sweet milk tea popular in East Asia, has

brought together activists in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Thailand who are critical

of Chinese nationalist netizens and who oppose Beijing’s new national security

law. Recently, the Milk Tea Alliance spread to the Philippines, where some

citizens have joined the online movement to voice concerns about Chinese

aggression in the South China Sea.

But what many in Hong

Kong, Taiwan, and other Asian countries see as online mobilization in support

of universal democratic norms, Beijing sees as a dangerous movement of

“splittists” who seek to undermine China’s sovereignty, keep China permanently

divided, spread Western values, and contain China in Asia. Indeed, Chinese

authorities regularly blame “external hostile forces” for the protests in Hong

Kong, and for the movement’s resonance in Taiwan and elsewhere.

Xi's China Dream

China’s leaders have

always maintained that they are prepared to use force over Taiwan, either to

prevent the island’s de jure independence or to compel its unification with the

mainland. But Xi has taken a progressively harder line on Taiwan, in word as

well as deed. At the 19th Party Congress in 2017, he declared that

reunification was linked to his “China Dream” of national rejuvenation. Since

then, he has twice stated that the separation of mainland China and Taiwan “should

not be passed down generation after generation.” And in his most recent

speech focused solely on Taiwan, in January 2019, he said that “our country

must be reunified, and will surely be reunified.”

Even more ominous,

Chinese Premier Li

Keqiang omitted the term “peaceful” in front of “unification” previously

standard in official communications about Taiwan, in his annual opening speech

to the National People’s Congress in May. A few days later, State Councilor and

Foreign Minister Wang Yi did the same in his speech to the congress. As a

former head of the State Council’s Taiwan Affairs Office, Wang was well aware

of the significance of this rhetorical change. By the end of the NPC’s two-week

session, “peaceful reunification” was back in the final version of Li’s work

report approved by the congress, along with unconvincing explanations for its

initial absence having to do with poor bureaucratic coordination.

In addition to

hardening its rhetoric against Taiwan, China has sought to isolate the island

diplomatically. In the last five years, Beijing has poached seven of Taipei’s

formal allies, leaving only 15 countries that recognize Taiwan as an

independent country. At the height of the coronavirus pandemic in May, China

even excluded Taiwan from the annual meeting of the World Health Assembly in

Geneva, despite the island’s global leadership in containing and mitigating

COVID-19.

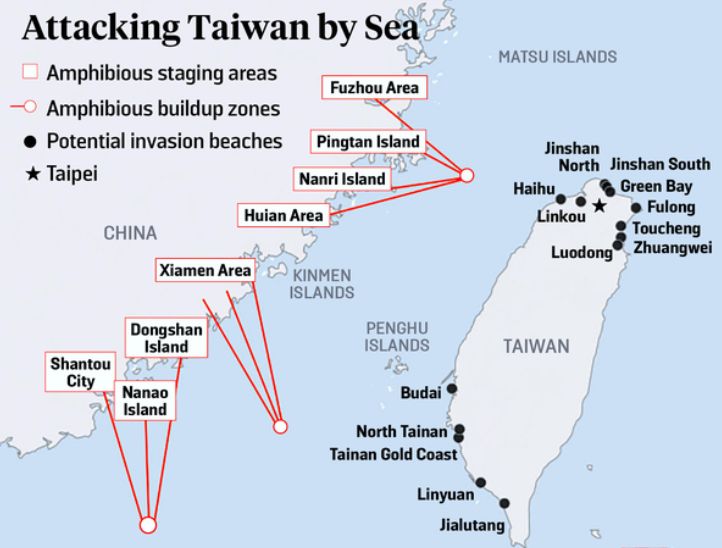

Invading Taiwan?

At the same time,

China has ramped up military pressure on Taiwan. Its air force and navy have

conducted more than ten transits and military exercises near the island since

mid-January, including an increasing number of deliberate incursions into

Taiwan’s airspace, according to research

by Bonnie S. Glaser and Matthew P. Funaiole of the

Center for Strategic and International Studies. In March 2019, China’s air

force sent two advanced fighter jets over the centerline of the Taiwan Strait

for the first time in 20 years. Since then, it has sent an increasing number of

aircraft across the centerline. China’s strategic bombers have also

circumnavigated the island multiple times in recent months, while other Chinese

aircraft have crossed the Miyako Strait between Taiwan and Japan. All of these maneuvers

were intended to intimidate Taiwan by demonstrating Beijing’s readiness to use

force at a moment’s notice.

Shortly after Taiwanese

president Tsai Ing-wen landslide reelection in January, the Chinese military apparently leaked a photo

depicting soldiers studying maps of Taiwan. Invasion routes are clearly marked

on the maps. One of the maps shows Chinese forces landing in southern Taiwan,

but only after seizing Penghu, a Taiwanese archipelago of 90 islets that lies

30 miles from the main island.

China has little

choice but to capture or suppress Penghu before invading Taiwan proper.

Taiwanese forces on the archipelago operate a long-range radar plus Hsiung Feng II

anti-ship cruise missiles and Sky Bow III surface-to-air missiles. If a

Chinese invasion fleet bypassed Penghu without destroying its garrison, the

fleet would be subject to missile strikes at its flanks.

It’s not for no

reason that Paul Huang, a researcher with the Taipei-sponsored Institute for

National Defense and Security Research, early this year described Penghu’s as

the most important of Taiwan’s three major island garrisons.

If China failed to

suppress or capture Penghu, the main invasion force “might be obliged to abort

the operation, making an assault on Taiwan one of history’s nonevents—like

Hitler’s invasion of England,” analysts Piers Wood and Charles Ferguson wrote

in a 2001 edition of the U.S. Naval War College Review. But taking the islands

could be hard for China. Their 60,000-strong permanent garrison includes an

army brigade with 70 upgraded M-60 tanks and an artillery battalion. The

Taiwanese navy routinely deploys a missile destroyer in the waters around

Penghu. The air force practices

staging nimble Indigenous Defense Fighters to the archipelago’s airport.

A

major beach-defense exercise in 2017 involved 3,900 Taiwanese troops, IDF

and F-16 fighters, AH-64, CH-47 and UH-60 helicopters, RT-2000 multiple-launch

rocket systems, tanks, 155-millimeter and 105-millimeter howitzers and teams

firing Javelin anti-tank missiles at offshore targets. The Taiwanese fleet

operates just two front-line submarines,

but in

the event of war it’s a safe bet that at least one of them would prowl near

Penghu.

There is little Tsai

can do to convince China to dial back the diplomatic and military pressure

short of accepting its unilateral definition of “one China” and its “one

country, two systems” model, both of which are now wholly discredited by what

has happened in Hong Kong. In the worldview of China’s leaders, Tsai’s

commitment to Taiwanese independence, she perceived efforts at “de-Sinification” on the island, and the growing

connections between Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the democratic world more broadly

all legitimize China’s saber-rattling, and perhaps, eventually, its use of

force. Xi appears to have made up his mind about Tsai, wrongly but perhaps

conclusively. He and other Chinese leaders are still weighing the costs and

benefits of a harder line on Taiwan as they take the measure of U.S. and

international willpower, which is why the U.S. response to the Hong Kong law

matters so much.

The USA to deter Beijing?

If so the US

administration (which US

defense agreement with Taiwan) might need to start by improving its

coordination with European and Asian allies. It has issued symbolically

important joint statements in Hong Kong, first with Australia, Canada, and the

United Kingdom and then with the G-7. But much more diplomacy is needed to

broaden that coalition and coordinate pressure on Beijing. That so few Asian

governments have criticized China’s new law is deeply worrisome, as is the

European Union’s initial

pledge that it will merely “follow developments closely.” But before

Washington can rally its European and Asian allies behind a unified message on

Hong Kong, it will have to stop kicking them. Trump’s unilateral withdrawal of

troops from NATO, his extreme demands for payment from Tokyo and Seoul, his

threats to pull troops out of South Korea, and his disinterest in the G-7 and

other groupings have pushed these allies away at a time when they would

ordinarily be open to U.S. leadership. These actions have also telegraphed

vulnerability, disunity, and lack of resolve among Western allies to

Beijing.

But China is creating

more favorable conditions for U.S.-led diplomacy in Hong Kong. Beijing’s

so-called wolf warrior diplomacy, aimed at

intimidating countries critical of its handling of the pandemic, combined with

its recent aggression on territorial issues has alienated much of the world.

The United States should seize this opportunity to make Hong Kong a diplomatic

priority. In the lead-up to the Legislative Council elections in Hong Kong in

September, Washington should lead the G-7, the Association of Southeast Asian

Nations, the European Union, and the so-called Quad of the United States,

Japan, Australia, and India in joint statements and actions warning Beijing

against arresting political candidates it dislikes.

The United States and

its European and Asian allies should also consider offering Hong Kong citizens

residency and a path to citizenship, just as the United Kingdom has done. And

if the situation in Hong Kong deteriorates, owing to arrests of candidates in

the September elections, for instance, the United States should consider

sanctioning the Chinese officials responsible. Such measures won’t restore Hong

Kong’s autonomy in the near term, but they could discourage overt acts of

repression and help shape Beijing’s thinking about Taiwan.

Staving off Chinese

aggression, whether in Taiwan or elsewhere in Asia, however, will also require

the United States to get serious about military deterrence in the western

Pacific. Over the last two decades, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has made

advances that seriously eroded U.S. military power in the western Pacific,

especially around Taiwan. Recent operations by two U.S. carrier battle groups

in the South China Sea were important demonstrations of willpower, but capacity

matters, too. As former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work has written,

the U.S. military now faces the prospect of losing a fight with China in

defense of Taiwan. The Pentagon has focused on building large platforms, such

as aircraft carriers and big-deck amphibious ships, but such facilities don’t

effectively deter China’s anti-access/area-denial capabilities. The United

States needs to rethink its forward-basing posture, increase its cooperation

and interoperability with allies such as Japan, and improve its ability to

fight in highly contested environments, including through greater use of

unmanned systems.

Washington could also

help Taiwan make its political system more resilient in the face of Chinese

pressure and its military better able to degrade Chinese capabilities in a

fight. The latter objective will not be served by selling the island the

billions of dollars’ worth of M1A2 tanks authorized by the Trump administration

in 2019. These do little to deter a combined naval, air, and missile campaign

from China, and the PLA will always be bigger and better equipped than Taiwan’s

army in a ground battle. Rather, the United States should work with Taiwan to

develop asymmetric

military capabilities that would actually stand a chance of deterring a Chinese

invasion or attacks on critical infrastructure.

Plus U.S. pressure

should also be tempered with skillful diplomacy to ensure that Beijing sees an

international coalition moving against it but doesn’t feel so threatened that

it lashes out or is able to separate the United States from its allies.

For updates click homepage here