By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Testifying before the

Senate Armed Services Committee in 2021, Admiral Philip Davidson, the retiring

commander of U.S. military joint forces in the Indo-Pacific, expressed concern

that China was accelerating its timeline to unify with Taiwan by amphibious

invasion. “I think the threat is manifest during this decade, in fact in the

next six years,” he warned. This assessment that the United States is up

against an urgent deadline to head off a Chinese attack on Taiwan—dubbed the

“Davidson Window”—has since become a driving force in U.S. defense strategy and

policy in Asia.

Indeed, the Defense

Department has defined a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan as the “pacing

scenario” around which U.S. military capabilities are benchmarked, major

investments are made, and joint forces are trained and deployed. Taipei has

been somewhat less fixated on this particular threat. But over the last decade,

as the cross-strait military balance has tilted in Beijing’s favor, Taiwan’s

leaders have ramped up their military spending and training expressly to deter

and deny such an attack.

The threat of an

amphibious invasion, however, is the wrong focal point for the United States’

efforts to protect Taiwan. China’s patient, long-term Taiwan policy, which

treats unification as a “historical inevitability,” together with its modest

record of military action abroad, suggests that Beijing’s more probable plan is

to gradually intensify the policy it is already pursuing: a creeping

encroachment into Taiwan’s airspace, maritime space, and information space. The

world should expect to see more of what has come to be known as “gray-zone

operations”—coercive activities in the military and economic domains that fall

short of war.

A screen broadcasting Chinese naval exercises near

Taiwan, in Beijing

This ongoing

gray-zone influence campaign will not itself force Taiwan’s formal unification

with the mainland. But over the course of many years, the expansion of China’s

military, paramilitary, and civilian operations into Taiwan’s recognized spaces

could reach certain intermediate objectives—most important, preventing the

island from achieving formal independence—while preserving Beijing’s options to

use force down the road. Left unchallenged, Beijing’s gray-zone campaign could

also demonstrate the limits of the United States’ power in Asia. The United

States and its allies are unlikely, for instance, to use the advanced missile

systems they have built up in the region if China never provides a clear casus

belli in the form of a brazen invasion. Instead, U.S. leaders may find

themselves mired in debates over whether China has crossed a redline. With

Washington hamstrung by uncertainty over how far China intends to push its

gray-zone tactics, much of the responsibility for countering China’s campaign

of encroachment will fall to Taiwan.

Although Taiwan’s

leaders frequently draw attention to China’s coercive activities in and around

the Taiwan Strait, most of the major military investments they have made in

recent years—including fighter aircraft, tanks, and an indigenously produced

submarine—are not well aligned with the insidious nature of the gray-zone

threat. Going forward, Taipei should concentrate its efforts on building buffer

zones across all domains, hardening its communications infrastructure, and

accelerating its foreign direct investment to build economic links that are

more resilient against Chinese disruption.

The United States

must also break its fixation on the prospect of an invasion and become more

alert to the dangers posed by a slow strangulation of Taiwan. Washington should

bolster Taipei’s efforts by augmenting Taiwan’s surveillance capabilities,

expanding the role of the U.S. Coast Guard across the South China and East

China Seas and around Taiwan’s maritime approaches, and coordinating with

commercial actors who may feel pressure to comply with Beijing’s restrictions.

If current trends persist, it is likely that the Davidson Window will come and

go with no war—but with Taiwan’s autonomy and the United States’ credibility

greatly diminished.

Darkening Clouds

Over the past decade,

China has asserted itself with increasing potency in East Asian airspace,

waters, and information sphere. Its coast guard and other maritime law

enforcement vessels have used nonlethal methods to gain varied levels of

control over waters disputed by Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines,

South Korea, and Vietnam. In the early months of 2024 alone, Chinese coast

guard vessels have undertaken dangerous maneuvers and fired water cannon to

prevent the Philippines from resupplying a military outpost, Chinese diplomats

have ignored the international Law of the Sea with new claims in the Gulf of

Tonkin, and Chinese vessels have warned off Japanese aircraft operating in

Japan’s territorial airspace around the Diaoyu Islands (known in Japan as the

Senkaku Islands).

These measures

reflect a fundamental intent to impose Chinese domestic law over disputed

territories. Although Hong Kong is more directly under Chinese control than are

the contested waters in the South China and East China Seas, Beijing’s steady

suffocation of the city’s autonomy resembles its strategy toward claimed

maritime spaces. China has implemented legal actions that expand its effective

control over critical aspects of Hong Kong’s governance, all without resorting

to military force.

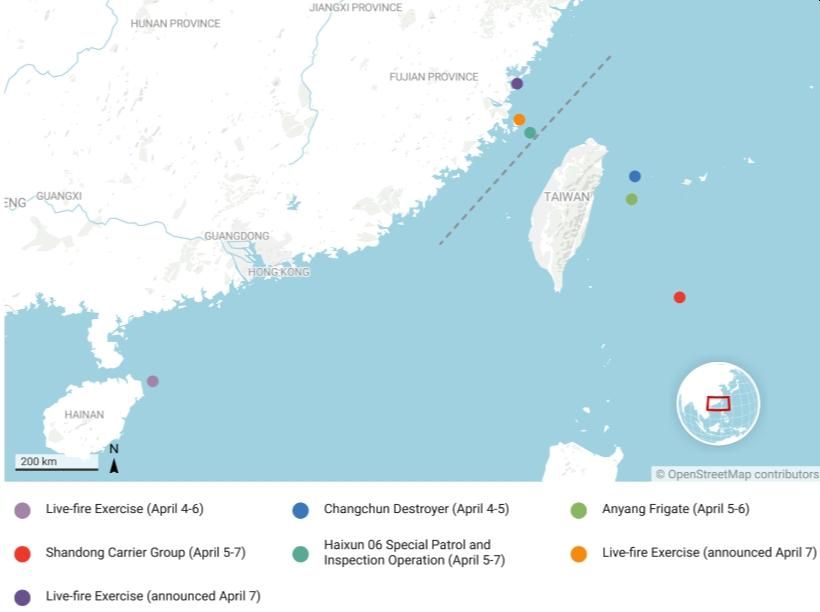

Taiwan has

increasingly become the target of coercive activities that resemble China’s

gray-zone repertoire in the South China and East China Seas. The Chinese air

force has conducted nearly three times as many incursions into Taiwan’s Air

Defense Identification Zone (the area in which aircraft are required to

identify themselves to Taiwanese authorities) since January 2022 as it did

between 2018 and 2021, according to reports released daily by Taiwan’s Ministry

of National Defense. Beijing has also routinely sent ships and aircraft across

the median line running through the Taiwan Strait, effacing a de facto boundary

that was defined in 1955. The Chinese military has increased the frequency,

intensity, and duration of live-fire drills that temporarily establish sea and

air control in the waters and airspace surrounding Taiwan, effectively

encircling the island. China’s formidable capabilities in information warfare

also figure prominently into its gray-zone concept of operations. Beijing

saturates Taiwanese media with disinformation and is suspected of cutting

submarine Internet cables to outlying islands under Taiwan’s control.

China’s gray-zone

activities in the Taiwan Strait should not be viewed as a mere prelude to an

amphibious invasion. Rather, Beijing’s persistent use of similar tactics in

nearby waters suggests such actions are the primary methods in a patient,

long-term strategy aimed at subjugating Taiwan without resorting to an

invasion. With this approach, China is attempting to choke off the island’s

control of surrounding waters and airspace and limit its ability to make

autonomous military, diplomatic, and economic decisions. Actions along these

lines would fall well short of the outright occupation that a successful

amphibious invasion might offer. Yet this more ambiguous campaign may yield

similar outcomes, leaving Beijing in control of Taiwan in most ways that matter

without the necessity of any formal capitulation.

Russia’s failure to

rapidly seize Kyiv after its 2022 invasion of Ukraine vividly reinforces the

appeal of this strategy. Since 2022, Beijing has shown increased interest in

cheaper and less risky measures to slowly squeeze the island, likely a

reflection of its recognition, following Moscow’s military struggles, that a

swift military victory over Taiwan will be difficult to achieve. China could

keep tightening the noose by rolling out more special coast guard patrols that

cover ever-greater swaths of the Taiwan Strait or by imposing customs or

quarantine measures to curtail commercial flows. These possible operations

would not stray far from activities Beijing has already undertaken around

Kinmen Island, for example. Such actions do not amount to a blockade in

operational or legal terms, but they achieve similar objectives and preserve

the option to conduct a more comprehensive and lethal campaign in the future.

Low Risk, More Reward

Because Davidson was

the most senior U.S. military officer in the Indo-Pacific and thanks to rising

concern across the U.S. national security community about the pace of China’s

military modernization, the Davidson Window was quickly accepted as dogma by

U.S. policymakers and military leaders. But a number of factors make an

outright Chinese military invasion less likely than a low-intensity

encroachment campaign, both before 2027 and well into the future. The Chinese

Communist Party has linked unification with Taiwan to the wider goal of

“national rejuvenation” by 2049, but Chinese leader Xi Jinping himself has

remained vague about what such unification means in practice. China can afford

to push its timeline well beyond the Davidson Window without departing from its

long-term policy toward Taiwan.

China is also limited

by a lack of recent combat experience and low confidence in its capability to

conduct joint operations. As long as Beijing’s coercive measures are expanding

its effective control over Taiwan, China is likely to keep traveling down this

well-worn path—one that can give it much of what it desires at a tiny fraction

of the cost of an amphibious invasion. The tepid response to China’s coercion

strategy thus far from the United States and its allies has done little to

discourage leaders in Beijing. Building and militarizing outposts on the

disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, evicting the Philippines from

Scarborough Shoal, and undermining Vietnam’s efforts to develop offshore oil

and gas fields by blocking Hanoi’s physical access to the sites are among a

litany of small successes that expand China’s control and build confidence in

its capacity to scale up those efforts.

Pursuing such a

gray-zone strategy entails some risks. China must carefully calibrate the

timing and extent of its coercive activities to avoid counterproductive

reactions from Washington and regional allies. Chinese actions to restrict or

sever critical flows of food, fuel, or information to Taiwan, in particular,

risk inviting symmetric responses from the United States. But the gray-zone

approach also offers distinct advantages. Beijing can rely heavily on law

enforcement and civilian assets in its activities against Taiwan, but the

United States lacks the nonmilitary maritime forces required to respond in

kind. Washington may turn toward economic or diplomatic measures, but these

cannot directly reverse China’s physical and operational gains and are unlikely

to impose costs sufficient to force China to change course.

The United States has

struggled to coordinate effectively with allies and partners to prevent China’s

progressively more coercive gray-zone actions. As long as Beijing does not

directly impede the flow of commercial traffic through the Taiwan Strait, most

countries are likely to remain on the sidelines. Some foreign actors, including

China’s regional neighbors and commercial entities such as shipping firms,

would likely accommodate many types of new restrictions Beijing might place on

Taiwan. Multinational firms have already set a worrisome precedent of deferring

to Beijing: Japanese and South Korean firms, for example, have for years

deferred to Beijing’s notification rules (as opposed to those set by Taipei)

for commercial flights traveling over the Taiwan Strait.

Key Change

If the United States and

Taiwan remain narrowly focused on the Davidson Window, they will make decisions

that are poorly matched to China’s more probable strategic choices. Investments

in precision munitions and the forward deployment of large numbers of U.S.

warships and aircraft in Asia are mismatched against Chinese actions calibrated

to stay just beneath the threshold that would make these assets useful.

Similarly, Taiwan’s pursuit of high-end military hardware such as submarines

and fighter jets and upgraded military training focused on repelling Chinese

invaders will do little to impede China’s creeping exercise of coercive control

through law enforcement and other nonlethal tactics.

Instead, Taiwan

should take the lead in proactively pushing back on China’s encroachment by

creating buffer zones that protect its airspace, waters, and economy. Calling

attention to Chinese gray-zone operations will not be sufficient on its own.

Taiwan would benefit from focusing its defense investments on domain-awareness

capabilities—for instance, acquiring more advanced ground- and sea-based

sensors to better detect and monitor the presence of Chinese aircraft and ships

in nearby airspace and waters. It should also build a large fleet of

inexpensive air and sea drones that could support surveillance operations in

Taiwan’s outlying areas and respond to the staggering scale of Chinese

incursions at a reasonable cost. Taiwan must also expand its coast guard to

more assertively push back against the activities of China’s coast guard and

maritime militia. Taipei has made some modest steps in these directions but is

moving far too slowly to meet the challenges posed by China’s intensifying

campaign. Taiwan will need to quickly increase its spending on the development

of indigenous capabilities and focus any foreign military financing from the

United States on these types of systems.

In the information

domain, Taiwan should harden its communication systems and train a more

sophisticated cyber defense workforce. Even more important, Taiwan must

accelerate its efforts to expand and diversify its satellite communications

services and infrastructure to defend against Chinese attacks on its

information networks and submarine Internet cables. Already, Taiwan has signed

a contract with Eutelsat OneWeb—an analog to the Starlink system that has proved so vital in Ukraine—but it

should take further steps to augment satellite bandwidth in the near term.

Washington will also

be crucial to Taiwan’s buffer zone strategy. In April, Congress earmarked $2

billion for defense aid to the Indo-Pacific, but how this money will be

allocated remains unclear. The United States should use a portion of available

funds to bolster Taiwan’s aerial and maritime surveillance and intelligence

capabilities and its fleets of air, sea, and subsurface drones. Washington

should also consider an expanded role for the U.S. Coast Guard in and around

the Taiwan Strait. Currently, U.S. Coast Guard forces patrol the exclusive

economic zones of U.S. allies such as Japan and the Philippines, uphold the

international Law of the Sea, and engage in exercises with regional partners.

Extending the Coast Guard’s mandate in waters near Taiwan to include, for

example, patrolling nearby fisheries to ensure access and support resource

conservation could push back against China’s efforts to control these areas

while matching Beijing’s use of law enforcement vessels. Using Coast Guard

vessels is less likely to provoke escalation than employing the U.S. Navy and

better suits a policy aimed at preserving the fragile status quo.

Finally, the United

States ought to coordinate with corporations to support Taiwan’s economic

buffer, especially those that ship goods to the island via sea and air. An

interagency group from the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, and State

should establish channels to assess emerging risks and share early warning

indicators with the leaders of large multinational trading firms, shippers, and

insurers. This exercise should be conducted in a private setting to facilitate

contingency planning and provide governmental and military support for these

corporations to undertake physical and financial preparations that will ensure

Taiwan’s access to global markets.

If the best predictor

of future behavior is past behavior, the United States and Taiwan should be as

focused on developing strategies to prevent Taiwan’s slow subjugation as they

are on forestalling outright invasion. If Washington cannot alter its single-minded

outlook, it could end up as a bystander as Taiwan slips under creeping Chinese

control in a silent fait accompli.

For updates click hompage here