By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Seven years

in Tibet and the Chinese interference

In part one, we covered a

new brand of diplomacy taking hold in Beijing, and its chief architects have a

suitably fierce nickname to match their aggressive style, which is all due to a

movie; they are the wolf warriors. Twelve days

after its premiere, Wolf Warrior 2 was not just the highest-grossing movie of

the year; it was the highest-grossing movie in China’s history.

Where underneath, we will

chronicle why the head of strategic planning for the Walt Disney Company

flew to Washington DC to explain Disney’s decision to make a movie, but

the Chinese continued to be resolutely opposed to making this movie.

Hence the head of strategic planning next felt the need to approach

the former secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, for help.

Tibet in Beijing

The main

entrance of the Tibet Hotel is seen behind a police vehicle parked outside the

hotel at the 2022 Winter Olympics, Friday, 11 Feb. 2022, in Beijing. People

attending the Beijing Winter Olympics can’t visit Tibet because they’re in

China’s “closed loop” system for foreign visitors. But some visitors, including

part of the Associated Press’ Olympics team, are getting a taste of the region

because they’ve been assigned to the Tibet Hotel. The hotel has been built and

outfitted to evoke the remote area on China’s western edge.

One of the hotel’s two restaurants, Shambhala, a reference from Tibetan

Buddhism to a mythical kingdom hidden in the Himalayas, is decorated with

prayers wheels along one wall. It’s closed during the Olympics because there

aren’t enough diners.

This Chinese belief in Shambhala essentially (and we don’t claim that

is where Chinese believers got it from) goes back to Saint Yves d’Alveydre, Mission de l’Inde en Europe. According to Sven Hedin, Ossendowski

and the Truth,1925, was then borrowed by Ferdynand Ossendowski

in his highly popular Beasts Men and Gods, where Ossendowski

claims that he had heard about it in Mongolia included a subterranean

realm of 800 million inhabitants called “Agharti”; of

its triple spiritual authority “Brahytma the King of

the World.”

This wasn’t Ossendowski’s first

literary fraud, as historian George F. Kennan has pointed out, he was

also co-creator of the so-called “Sisson

documents.”

The backgrounds story of

the movie, which we covered early on, presented extensive details about the

original German expedition the Brad Pitt movie referred to.

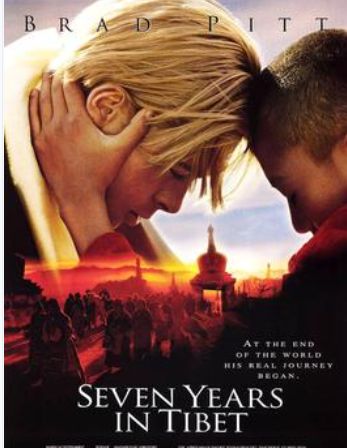

A government relations

executive at Sony Pictures Entertainment received a perplexing phone call that

concerned a politically sensitive movie called Seven Years in Tibet. Brad

Pitt and David Thewlis were stars, with music composed by John Williams with a

feature performance by renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

Howard Stringer, Sony Corporation of America’s top executive, explained

that the film had been shown to some Chinese officials. It had so offended them

that there was no concern that they might expel all Sony business from the

country.

Work on Seven Years in Tibet had begun innocently enough. In the early

1990s, Jean-Jacques Annaud, a French director known for little-seen but

well-respected art house movies like The Bear and The Lover, was drawn to Asia

after filming a movie in Vietnam. He had a strong desire to return and explore

the continent’s spirituality and asked his assistant for books he could adapt

into movies on the theme. She brought him Heinrich Harrer’s memoir. Harrer was

a mountaineer who’d left Nazi Europe to summit Nanga Parbat in British India,

only to be taken prisoner, and eventually finds himself tutoring a teenage

Dalai Lama as war broke out between Tibet and China. “Fabulous,” thought Annaud

as he read the book and assessed its cinematic potential. “Here’s a blond Aryan Nazi who becomes the teacher of

the Dalai Lama.” Brad Pitt, Hollywood’s most famous blond, got the part.

The movie was perfectly timed for the Dalai Lama’s star-making moment

in Hollywood. He was born in a shed and identified as the fourteenth

incarnation of the Dalai Lama at four years old. Now the docile monk lived in

Dharamsala, where a government-in-exile of about 113,000 Tibetans sandwiched

between China and India is based. As the repression of Tibet grew, the Dalai

Lama’s public persona rose. In 1989 he won the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1992 he

guest-edited the December issue of French Vogue.

The following year, Richard Gere, star of An Officer and a Gentleman

and Pretty Woman, went off-script before announcing the winner for Best Art

Direction at the Academy Awards to decry the “horrendous, horrendous human

rights situation” in Tibet. Sharon Stone called herself a disciple. In a 1997

ceremony in India attended by 1,500 monks and nuns, Steven Seagal, the star of

ultraviolent revenge fantasies like Hard to Kill, was anointed

a tulku, a “reincarnated lama and radiant emanation of the Buddha.”

Disney’s ABC put Dharma & Greg, about a young American woman embracing

Buddhism, on its prime-time lineup. A charming monk who encouraged others to

shun all earthly possessions had become the patron saint of Beverly Hills.

His Holiness was so popular that soon there were not one but two movies

about him underway. Also, among those taken in were E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

screenwriter Melissa Mathison and her husband, Harrison Ford, already a fixture

in the Hollywood firmament as the star of Star Wars and Raiders of Lost Ark.

The couple had traveled to Tibet in 1992 and met a tour guide, Gendun Rinchen, who China accused of being a spy and

imprisoned for nearly a year. Mathison was preparing to write Kundun, a

screenplay about the Dalai Lama’s teenage years. Mathison wanted to ground

Tibet in the story of the real people caught in a political and spiritual

tinderbox. “Part of the tragedy of Tibet is that it’s been Shangri-La” in

Hollywood movies, she said, presented as a caricature and not as a pressing

humanitarian crisis. “Nobody believed it existed in the first place, so its

destruction was the destruction of a fantasy.” She began telling associates in

Hollywood that hers would be the original Dalai Lama production of 1997; she

and Ford had flown to India and read the Kundun script with the man himself.

Martin Scorsese came on board to direct. Then the Dalai Lama, ever the

diplomat, also endorsed the story that had inspired

Seven Years in Tibet.

“Harrer is one of the few Westerners who

[are] fully acquainted with the Tibetan way of life. His book is beautiful and

good,” the Dalai Lama said. He added, “Since I was 15 or 16, there has been a

tragic situation in my country, and most of my life has been spent under

difficult circumstances. Buddhist teaching has helped me to retain hope and

determination in this time, so perhaps a story about such a person must be a

good thing.”

We are

resolutely opposed to the making of this movie

The history that both Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet explored was

nearly fifty years old, but it was fresh in the minds of Chinese officials. China invaded Tibet in 1949, its soldiers sweeping

through the region and ordering monks to reeducation camps. Soldiers destroyed

religious temples and killed villagers. Bronze statues from the area were

melted down for copper. A decade later, Chinese soldiers handily defeated a Tibetan

insurrection, and the Dalai Lama escaped to India, worried his murder or

capture would spell the total end of Tibetan Buddhism. He still lives there

today; his power is defined more by where he cannot go than by where he can. To

Americans, Tibetans can be viewed as spiritual brethren to their country’s

colonists, persecuted for their beliefs, and forced to find refuge elsewhere.

But to many Chinese, the Tibetans’ argument for sovereignty, as one scholar put

it, is akin to an American hearing about a “rally calling for Hawaii to be

returned to the descendants of the last king of those islands.” His mere

presence - let alone his star power - is a one-person rebuke to what China

considers its rightful borders. At least one U.S. executive knew making a movie

about this history was bad for business.

Edgar Bronfman Jr., the CEO of the beverage company Seagram, acquired

Universal Studios in 1995. Scorsese had a distribution deal with Universal at

the time, but things quickly grew tense between him and the new owner. The

director had recently wrapped his three-hour epic Casino, and Bronfman wanted

him to cut forty-five minutes from the film to make it commercially viable.

Scorsese refused, prompting Bronfman to wonder why a studio had employees if

they wouldn’t listen to the boss. Then Scorsese brought the boss Kundun.

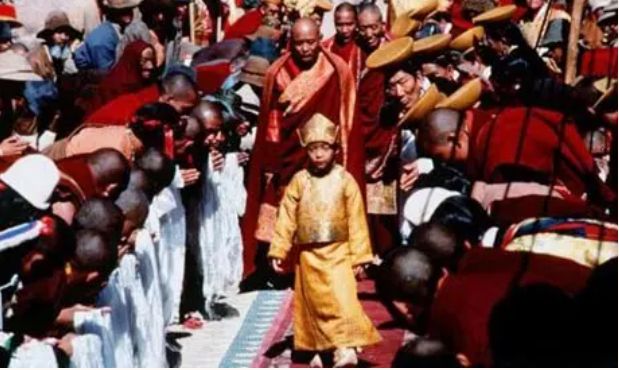

Kundun tells the story of the early life of the 14th and current Dalai

Lama, born in 1935 in Amdo, Tibet (now part of Qinghai, China). Tibetan

Buddhists believe the Dalai Lama to be the reincarnation of Chenrezig, a

legendary bodhisattva (someone who seeks enlightenment to help others), and

look to him as their political and spiritual leader.

“I’m not doing this. I don’t need to have my spirits, and wine business

was thrown out of China,” Bronfman said. Through his beverage deals, Bronfman

was already aware of a principle Hollywood was learning in real-time: in China,

political mistakes are punished with economic sanctions. Alienating China with

a movie wasn’t about losing the paltry box-office sales it might yield. It was

about allowing that movie to become a contaminant in the larger corporate

structure, one that put far more significant revenues at risk. For Sony, China

threatened disruption of an electronics supply chain that would cost billions

to rebuild. At Disney, where Scorsese took the project after Bronfman’s

refusal, it was the TV channel, theme park, and Mickey Mouse plush dolls that

might not pass through Chinese borders because

of a midbudget drama being made through a production deal signed by a

subdivision of a subdivision.

Chinese officials didn’t care what the studio executives knew or when.

“We

are resolutely opposed to the making of this movie,” said an official in

China’s film bureau of Kundun months before it was scheduled to hit theaters.

“It is intended to glorify the Dalai Lama, so it is an interference in China’s

internal affairs.”

When had a movie release ever been received with the language of spycraft? For the first time, a certain kind of message had

been sent from China to Hollywood at large, as effective as if couriers had

been dispatched to every office with a telegram. There’s a saying in Chinese, shā jī jǐng

hóu, which roughly translates to “kill the

chicken to scare the monkeys.” The chicken was the person who could be made

a public example of; the monkeys were everyone who watched and learned from

that person’s mistake. The cases of Seven Years in Tibet and Kundun were the

first clash of Hollywood moviemaking with Chinese politics. Still, as the

industry’s entanglement with China grew, Sony and Disney would have a lot of

companies in the coop.

When officials in the town where the Seven Years in

Tibet production was based, Ladakh’s border region told the film crew that

India, under pressure from China, had threatened to cut off their electricity

if filming continued, then the production was denied permission to open a local

bank account. Cutting off the power was one thing. Cutting off the money was

another, and Chinese pressure stopped the production for the thirty minutes it

took the film crew to secure permission to move Seven Years in Tibet to a

friendlier country.

The cast and crew hence decamped to the Andes Mountains along the

border of Chile and Argentina. This range broached the same altitude as their

original location in Ladakh but was safely located halfway around the world.

Laborers reconstructed Lhasa. The roughly one hundred monks cast in the movie,

some of whom had signed their contracts with purple-inked thumbprints, flew to

South America, crying when they saw the movie-set simulacrum of their lost

city. They were a lot cast out by the world. The Argentine government had

limited the number of monks granted entry, worried they would stay and form a

politically problematic settlement. When Argentinian customs agents wouldn’t

allow Asian yaks in, fearing they carried disease, the

director Jean-Jacques Annaud’s crew sourced new yaks from

Montana. These yaks stepped off the cargo plane and into roles for which they’d

been miscast; they were not, Annaud realized, working yaks but “yak de

Compagnie,” accustomed to a life of leisure on the Montana prairie and unprepared

to haul heavy bags on their backs. Two were eventually trained to the point

that Annaud could get the shots he needed. Annaud had effectively re-created

Tibet in the Andes, though modern life would sneak in every morning when

Argentinian teenagers screamed for Pitt as his motorcade rode into a set.

When she sat down to watch the completed film soon after receiving the

call from her studio’s CEO, Hope Boonshaft had

only a cursory understanding of Chinese politics. Still, it didn’t take a

sinologist to see why China would be offended. The movie opens with a toddler

Dalai Lama, still missing a few teeth, receiving gifts from prostrating

Tibetans. After Harrer’s capture, the Dalai Lama, now a young boy, is drawn to

the white man who teaches monks how to ice-skate. Harrer (along with

moviegoers) learns what China doesn’t want anyone to know: his surrogate son is

the spiritual leader of millions. They understand the rarefied world he lives

in, where no one is ever to be seated higher than him, speak before he does, or

look him in the eye. Harrer becomes his tutor of the outside world, telling him

where Paris is, who Jack the Ripper was, what a Molotov cocktail can do.

Harrer, in turn, adopts the Tibetan sensibility: he respects all living

creatures and learns the omen that an asteroid portends. In this case, the evil

omen is Mao, who a radio broadcaster tells us has

consolidated power and vows to reclaim Tibet.

China had reason to fear the way the movie presented it. Chinese

soldiers mow down statues of Buddha with machine guns, bomb villages, and chase

out terrified citizens. The Chinese send officials to reason with the Dalai

Lama, offering autonomy and religious freedom if China accepts its political

master. The Dalai Lama’s teachings of nonviolence and compassion make the

Chinese officials look like boorish fools. Harrer leaves Tibet a changed man,

of course, one who reconnects with his estranged son and at one point plants a

Tibetan flag atop a mountain. The movie’s final image: text on the screen

reminding the audience of the one million Tibetans dead at the hands of the

Chinese occupation.

The lights came up in Boonshaft’s screening

room on the Sony lot. Years later, Sony would learn how easy it was to cut a

single scene or line of dialogue from a movie to get approval from Chinese

censors, but this was a 130-minute humanization of a Chinese state enemy and an

assault on its most sensitive political issue. Boonshaft

hustled to manage damage control, calling Jim Sasser, an old friend from

Washington who served as U.S. ambassador to China. He recommended she

immediately acquaint herself with local Chinese officials and study Mandarin.

It was all a matter of building up guanxi, the Chinese mixture of etiquette and

politesse that undergirds every relationship in Chinese professional circles.

More than simply networking or quid pro quo arrangements, guanxi is a level of

trust that must be established before any deal is completed or truce reached.

Hope Boonshaft’s first step toward building

it: traveling across town to introduce herself to the Chinese consul and the

Chinese cultural attaché in Los Angeles. Her second step: going to the Tiffany

in Beverly Hills to buy offertory presents (she had already learned not to give

them clocks, since the Chinese view such gifts as a death omen). Her third

step: doing whatever she could to get in their good graces. Even in 1997, Boonshaft could see that China’s top priority was to spread

its influence abroad. She started screening local Chinese movies on the Sony

lot, another suggestion of Sasser’s that meant the world to Chinese officials

trying to develop the credibility of their film industry. The screenings were

by invitation only, and the consulate managed the guest list. The movies

themselves were not high priorities for Sony, but the expense of dessert for

the receptions afterward was a small price to pay if it built up goodwill.

Those Chinese officials cheered to see Sony executives drop by unannounced and

express interest in China’s entertainment industry did not know that Boonshaft had invited them for the charm offensive.

She brought herself up to speed on the history of China’s relationship

with Japan, learning about the Battle of Nanjing, the six-week massacre of some

three hundred thousand Chinese civilians at the hands of Japan’s Imperial Army.

The so-called Rape of Nanjing had occurred sixty years prior, but the Chinese

had never forgotten the murders - or Japan’s refusal to apologize for them.

Sony, Japan’s best-known company, did business with China, but Boonshaft always sensed tension. Now the Chinese were

unhappy about a movie whose release was still months away.

No matter: Chinese officials took advantage of Sony’s willingness to

please. The country asked Sony and the other studios to support its bid to join

the World Trade Organization - a request they all accommodated. They asked Sony

to sponsor a table at a Los Angeles event honoring the Chinese prime minister -

a proposal it accommodated. Boonshaft hosted a

Mandarin tutor in her office each week to demonstrate her commitment to

celebrating their culture.

Disney CEO Michael Eisner and his team needed to find the least

bad option. They had weighed shutting down the movie before the situation had

gone public but knew doing so would risk Scorsese’s wrath. The director would tar them in the press as bowing to a totalitarian regime,

and the rest of the industry would rally against Disney for silencing the

director. China’s threats challenged a core tenet of Hollywood, especially of

filmmakers like Scorsese, who’d been inspired by the European auteurs of the

mid-twentieth century. Movies were a business, to be sure. Still, they were

also a vehicle of American expression, an industry where filmmakers were

unafraid to take on - were even celebrated for taking on - politically charged

topics.

Disney ultimately decided on a Goldilocks option: release the movie,

but as quietly as possible. They would spend as little money as possible to

market the film in a limited release. Once that dearth of marketing led to

lousy returns in its opening weeks, Disney would have justification to tell

Scorsese that it wasn’t worth expanding to theaters nationwide. Still, no one

in Hollywood could argue that Disney had censored it.

Kundun

Peter Murphy, the head of strategic planning for the Walt Disney

Company, flew to DC to explain Disney’s decision to the Chinese. He brought

Henry Kissinger with him. The diplomat didn’t say much, understanding that his

role was to sit and lend some gravitas to the situation. He joined Murphy on

one side of the table; more than half a dozen Chinese officials faced them.

Murphy told the Chinese that the limited release for Kundun was good for them

since it would avoid any critics saying China had censored a Hollywood movie.

Neither was it. Coincidentally, Kissinger came aboard as Disney was

planning the release of the Martin Scorsese film “Kundun.”

All of that promise and ambition were suddenly endangered in 1996

when Peter Murphy, the head of strategic planning for the Walt Disney

Company, received a phone call to his Los Angeles office. It was the

Chinese embassy in Washington. An official there had called Disney’s general

line and been directed to Murphy. “You started, in the last forty-eight hours,

shooting a film about the Dalai Lama called Kundun, the embassy official

said.

As the embassy official had said, his colleagues told him that it was a

drama being directed by Martin Scorsese about the Dalai Lama. It had taken only

two days after cameras started rolling for word of the production to travel

from its set in Morocco to Beijing, where officials were not happy. After

learning about the film and the story, Murphy realized that making this movie

endangered Disney’s entire future in China. He didn’t know it at the time, but

that phone call to his Burbank office was the start of a cautionary tale for

all of Hollywood; it was a sign that the capital offered in China was

inextricably tied to politics. On the afternoon of the call from the Chinese

embassy, a future in which China would exercise remarkable power in Hollywood -

the ability to green-light projects and change scripts like an invisible

studio - began

to take shape.

In the meantime, though, Murphy needed to put out this fire. He called

the person who was already on retainer to help Disney navigate the Chinese

power structure and who served as United States Secretary of State and National

Security Advisor under the presidential administrations of Richard Nixon and

Gerald Ford.

Henry

Kissinger listened to Murphy as he laid out the Kundun issue. Murphy’s mind

was racing with the implications it might spell for Disney’s plans in China,

but the former secretary of state remained unfazed by the whole thing. Granted,

Kissinger had negotiated Nixon’s meeting with Mao Zedong in 1972, a détente

that reorganized the world order. Given China’s economic growth and the

political power it had accrued since Nixon and Mao shook hands in Beijing, it

was fitting that, twenty-four years later, he would be called in to save Mickey

Mouse.

When next Murphy flew to DC to explain Disney’s decision to the

Chinese. He brought Kissinger with him. The diplomat didn’t say much,

understanding that his role was to sit and lend some gravitas to the situation.

He joined Murphy on one side of the table; more than half a dozen Chinese

officials faced them. Murphy told the Chinese that the limited release for

Kundun was good for them since it would avoid any critics saying China had

censored a Hollywood movie.

“You do not want us to kill this film. It’s not good for either of us,”

he explained, parsing his words to avoid using the word apology. He expressed

regret for “the situation we find ourselves in” - not for making the movie. But

the Chinese didn’t understand.

Across town at Sony Pictures Entertainment, a government relations

executive named Hope Boonshaft received a perplexing

phone call of her own only a few months later, in the spring of 1997. Of all

things, it also concerned a politically sensitive movie about the Dalai Lama,

this one called Seven Years in Tibet.

Howard Stringer, Sony Corporation of America’s top executive, explained

that the film had been shown to some Chinese officials. It had so offended them

that there was no concern that they might expel all Sony business from the

country. The film wasn’t just putting Sony movies at risk; in the mid-1990s,

the Chinese box office could have hardly covered a few executive salaries

anyway. It was threatening “big Sony,” as employees put it - the manufacturer

of computers and televisions that had led Japan’s electronics boom since its

founding just after the end of World War II. The prospect of losing access to

China’s factories and customers meant billions of dollars were on the line.

Work on Seven Years in Tibet had begun innocently enough. In the early

1990s, Jean-Jacques Annaud, a French director known for little-seen but

well-respected art house movies like The Bear and The Lover, was drawn to Asia

after filming a movie in Vietnam. He had a strong desire to return and explore

the continent’s spirituality and asked his assistant for books he could adapt

to the theme’s film. She brought him Heinrich Harrer’s memoir. Harrer was a

mountaineer who’d left Nazi Europe to summit Nanga Parbat in British India,

only to be taken prisoner, and eventually finds himself tutoring a teenage

Dalai Lama as war broke out between Tibet and China. “Fabulous,” thought Annaud

as he read the book and assessed its cinematic potential. “Here’s a blond Aryan

Nazi who becomes the teacher of the Dalai Lama.” Brad Pitt, Hollywood’s most

famous blond, got the part.

For updates click hompage here