By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

How to Hold Syria Together in the Wake

of Assad’s Fall

Until Bashar al-Assad

fled Syria, on December 8, few countries wanted the Syrian dictator’s government

to fall. This was not because foreign governments liked Assad or approved of

the brutal way in which he reigned over Syria. Rather, they were afraid of what

might replace him: rule by extremist militants, sectarian bloodletting, and

chaos that could engulf not just Syria but much of the Middle East.

That fearful vision

was also the Assad government’s argument for itself, that its

continued survival kept anarchy and carnage at bay—and many people, including

foreign policymakers, were convinced of it. In 2015, when opposition militants

came close to toppling Assad, U.S. officials regarded the possibility of

outright rebel victory and regime collapse as tantamount to “catastrophic

success.”

Now Assad is gone.

Syrians are celebrating in the streets of Damascus, opposition groups are

attempting to organize a political transition, and the world is about to find

out what comes after the fall. Assad remained ruthless and cruel to the end,

even as he presided over an increasingly impoverished and dysfunctional state.

He leaves a shattered country in his wake, and any new government—never mind a

coalition of fractious armed opposition groups—would struggle in these

circumstances. But the poor record of Syrian rebel groups when they have ruled

significant stretches of territory also makes it difficult to be optimistic.

Still, it is in

everyone’s interest that Syria succeeds. Syrians do not want to

endure further strife and devastation, and the international community cannot

afford to see Syria fall apart. Interested countries now need to do

everything they can, including encouraging a peaceful, inclusive transition and

providing ample humanitarian and economic assistance, to ensure that the worst

fears about post-Assad Syria do not come to pass.

The Fall of Assad

In 2011, the Assad

government attempted to crush a nationwide protest movement. Those protests

became an armed rebellion, which Assad met with ferocious, escalating violence.

At several points in the ensuing war, Assad’s government seemed in real danger of

being overrun by opposition militants. Interventions by Syrian allies Iran

and Russia, however, stabilized the government militarily and enabled it

to regain ground. Between 2015 and 2020, Assad bombed opposition-controlled

enclaves across Syria into submission and retook most of the country.

The war then entered

an extended stalemate. Turkey secured several remaining

opposition-held pockets in Syria’s north, while the U.S.-backed Syrian

Democratic Forces, or SDF, controlled Syria’s east, including the country’s

most valuable agricultural and petrocarbon resources.

Thanks in part to new U.S. sanctions and neighboring Lebanon’s economic

meltdown, the whole of Syria—but government-held territory most of all—was

plunged into a deep economic crisis. Syria’s state institutions and military

progressively weakened, and the government proved too resource-starved to

stabilize and rebuild opposition-held areas it had recaptured.

But this year,

with Iran and Russia entangled in other conflicts, what remained of

Syria’s armed opposition seized the opportunity. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham—the

Syrian Liberation Group, or HTS—and other opposition factions had been

organizing for years in a Turkish-protected bastion in Syria’s northwestern

province of Idlib. On November 27, these groups launched an offensive on the

northern city of Aleppo. When they broke through the Syrian army’s defenses and

seized the city, that set off the cascading failure and collapse of Syria’s

military nationwide. HTS-led forces pushed south from Aleppo toward the

capital, Damascus, as Syrians in the country’s center and south—including in

formerly opposition-held areas—also rose up. On December 8, as opposition

factions closed in on Damascus from both north and south, Assad fled to Russia.

After more than 13 years of grinding civil war, the Assad government had

crumbled in less than two weeks.

Now, in a post-Assad

Damascus, HTS has taken the reins in attempting to manage an orderly political

transition. HTS has installed the interim Syrian Salvation Government, which it

created in Idlib, as a national transitional authority. It has also deployed

its security forces in the capital, established checkpoints on key transport

nodes across the country, and repeatedly warned triumphant opposition militants

against abusing civilians and looting.

Rebels In Charge

Many in Western media

and policy circles now evidently assume that HTS will govern Syria. Yet there

are reasons to doubt that things will be that simple. Until a few weeks ago,

HTS controlled two-thirds of a province on Syria’s rural periphery. Running all

of Syria will present a different challenge.

HTS is the latest

incarnation of the al-Nusra Front, originally the Syrian vanguard of the

Islamic State in Iraq and then al Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate. The group publicly

broke ties with al Qaeda and transnational jihadism in 2016, although it still

includes some veteran militants and foreign fighters in its ranks. It has been

designated a terrorist organization by the UN Security Council, the United

States, and other national governments.

In recent years, HTS

has worked persistently to rehabilitate its image and secure its removal from

international terrorist lists. As opposition forces marched on Damascus, HTS

and its leader, Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, attempted to project an image of seriousness

and moderation. HTS issued statements reassuring Syria’s diverse ethnic and

sectarian constituencies and various international stakeholders, while Jolani

gave interviews to Western media affirming Syria’s history of coexistence and

committing to institutional governance.

As HTS swept to

Damascus, its fighters appear to have remained relatively disciplined. Reports

of summary executions and sectarian reprisals were limited, perhaps due, in

part, to the way much of the Syrian army ceded territory without a fight. To be

sure, some retributive violence has clearly taken place, and thousands of

Syrians fearful of militant control have fled to Lebanon. But for the time

being, the victorious opposition has not unleashed a vengeful campaign against

its former foes or against communities widely associated with the old regime.

Unfortunately, HTS’s

record at the local level does not augur well for the construction of a

national government that accommodates Syria’s religious, ethnic, and political

diversity. The group has not shown any real commitment to political

pluralism in governing Idlib. HTS stage-managed some legitimating exercises to

establish its Salvation Government in Idlib, including an ostensibly inclusive

constitutional conference. Yet these were never open, participatory democratic

processes. Jolani was always in control, even though he did not hold an

official government portfolio; he was just understood to be the boss of Idlib.

Just months ago, HTS’s security apparatus violently put down protests in Idlib

demanding the release of detainees held by HTS and an end to Jolani’s rule.

HTS did manage to

create order and relative stability in Idlib. Yet it seems unlikely that HTS

will be able to reproduce its control over Idlib across the whole of Syria. The

consolidation of HTS control in Idlib was a years-long, frequently violent process,

in which HTS crushed rival opposition factions and eliminated its own

dissidents and defectors. It seems plausible that HTS could have extended its

administrative and security apparatus from Idlib to nearby Aleppo after it

seized the city. Scaling that model to cover the whole of Syria, however, seems

impossible. Syria is much larger geographically, has around ten times as many

people as Idlib, is more diverse, and is now teeming with armed men outside

HTS’s effective control. Although HTS may have fostered a strong culture of

internal discipline, the group, by one recent count, commands only 30,000 men.

That seems insufficient to govern Syria, or to control the many armed groups

that may swim in HTS’s wake.

HTS is not the

totality of Syria’s armed opposition. It was not even the whole of the armed

opposition in Idlib, where HTS marshaled allied factions that functioned as its

auxiliaries. HTS cannot control all the armed groups now active across the

country. Certainly, the factions that remobilized in the country’s center and

south over the past few weeks do not answer to Jolani.

When Syrian

opposition groups previously captured other parts of the country—including in

southern Syria, the countryside around Damascus, and in sections of northern

Syria captured by Turkish-backed groups—the result was typically arbitrary

militia rule and fratricidal infighting. Attempts to consolidate local factions

and build unifying institutions repeatedly failed. HTS succeeded in Idlib only

with a lot of time, persistence, and deadly coercion.

Many are now looking

to Turkey to use its sway over HTS and other opposition groups to help steer

Syria’s transition. But although Turkey has some influence over HTS, it does

not seem to control the group, which, for example, previously rankled the Turkish

government by seizing territory held by Turkish-backed groups in Aleppo. And

among opposition factions in northern Syria that are more wholly

Turkish-owned—on Turkey’s payroll, operating in Turkish-occupied areas that are

administered by Turkish-linked institutions—Ankara has demonstrated no ability

to impose discipline or curb abuses. Turkey has mainly just loosed these

factions on the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, which Ankara considers an

extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, a proscribed Kurdish militant group.

Even after the fall of Assad, Turkish-backed factions have continued to attack

the SDF in northern Syria.

There are reasons to

doubt the sincerity of HTS’s moderate turn. But the more immediate danger to

Syria is not Islamist extremism but the chaos that opposition victory might

unleash. There is a real risk that the situation in post-Assad Syria will spin

out of control and that the country will devolve into not only open conflict

between armed groups but also myriad individual acts of revenge and bloody

score-settling.

Set Up to Fail

Whatever dispensation

replaces Assad, this new government will not face auspicious conditions for

stability and recovery. Syria’s already crushing socioeconomic crisis seems

likely to deepen further. According to the UN, 16.7 million Syrians needed

humanitarian assistance in 2024, more than 70 percent of the country’s

population and the highest figure since the start of Syria’s war. Some 12.9

million Syrians are believed to be food insecure. State services had already

broken down before Assad’s toppling. In areas held by the Assad government, in

particular, electricity shortages had disrupted daily life and the provision of

public services such as education and running water.

HTS has limited

resources of its own. The group was able to maintain social stability in Idlib

thanks largely to internationally supported humanitarian assistance delivered

via Turkey. It remains a designated terrorist organization—it may now assume

power in an economically ruined Syria that was already extensively sanctioned.

It is not clear how a Syrian state apparatus and economy subject to numerous

overlapping sanctions regimes will work, or whether a necessary influx of donor

support will materialize. Assad’s longtime allies cannot be expected to keep

Syria afloat; already, Iran has apparently halted shipments of oil that were

critical for power generation. Humanitarian agencies have reported shortages of

essential goods and dramatic increases in food prices in major cities across

the country.

Some observers have

suggested that the fall of the Assad government could pave the way for the

return of Syrian refugees. The result, however, may be the opposite: new flows

of migration out of Syria. It was always an oversimplification to claim that

refugees who left Syria after the outbreak of the civil war in 2011 were all

fleeing the persecution of the Assad government; many were, but many others

were trying to escape general insecurity and violence, Syrian military

conscription, or socioeconomic collapse. For refugees to return in a

meaningful, sustainable way, Syria needs to be a place where people can

actually live—somewhere that is safe, with public services and reliable jobs.

Even Syrian refugees overjoyed at the fall of Assad will be unable to return

home if law and order breaks down or if they cannot find ways to support their

families.

Economic privation

could further encourage violent competition between Syrian armed groups over

territory and revenues. After more than a decade of war, these groups have

developed their own independent interests and needs. And the black markets of

Syria’s war economy will not just go away now that Assad is gone. For example,

Assad-linked actors—including groups that once opposed him—had been making

hundreds of millions of dollars trafficking illicit amphetamines. Control of

that trade now may stoke violence between competing factions.

New migration from

Syria and the resumption of internal conflict will have destabilizing effects

on Syria’s neighbors—even as those neighbors may themselves play a

destabilizing role inside Syria. Turkey has kept up a hard rhetorical line on

SDF “separatist terrorists” in Syria and has encouraged continued attacks by

its local proxies on Kurdish-led forces. Israel has bombed and destroyed Syrian

military facilities across the country and seized additional territory along

the Golan Heights. Some countries in the region, including Egypt, Jordan, and

the United Arab Emirates, are likely alarmed by the prospect of a militant

Islamist group taking power in Damascus. There is a real risk now that regional

countries could recruit local factions to secure their equities in Syria,

potentially by seizing territorial buffers along Syria’s borders. All of these

circumstances are unlikely to be conducive to a successful political

transition.

Averting Disaster

Assad will not be

missed. Under Assad and his father, Hafez, the Syrian government did heinous

things to maintain power, brutalizing and immiserating Syria’s people. The

relief of most Syrians at Assad’s departure is clear from the celebrations that

have filled the streets of Damascus and other cities and from the outpouring of

emotion at the opening of the government’s network of prisons and the

liberation of its detainees.

Now all parties need

to ensure that the darkest predictions about Assad’s fall do not come to pass

and that what replaces Assad is not just chaos and violence. Syrians themselves

will undoubtedly play the lead role in deciding the country’s future. Yet outside

countries can also help by encouraging HTS and other Syrian groups to pursue a

peaceful, maximally inclusive political transition. In parallel, donor

countries should advance a large program of humanitarian and economic

assistance for Syria, including aid for vulnerable Syrians and support for

essential services nationwide. They should provide immediate relief from

sanctions imposed on the previous Assad government, including waivers or

licenses neutralizing sanctions on state institutions such as Syria’s central

bank and on whole economic sectors. Outsiders should strongly discourage any

new factional conflict and resist the temptation to advance their own interests

by supporting one group over another.

Although some

countries may have understandable reservations about HTS, they should still

want Syria’s transition to succeed, and they absolutely should not interfere

and make it fail. The disintegration of Syria will be worse, for Syrians and

for the region. And if Syria sinks into chaos, it won’t just be a human

disaster—it will mean that the case for the Assad dictatorship has been

vindicated.

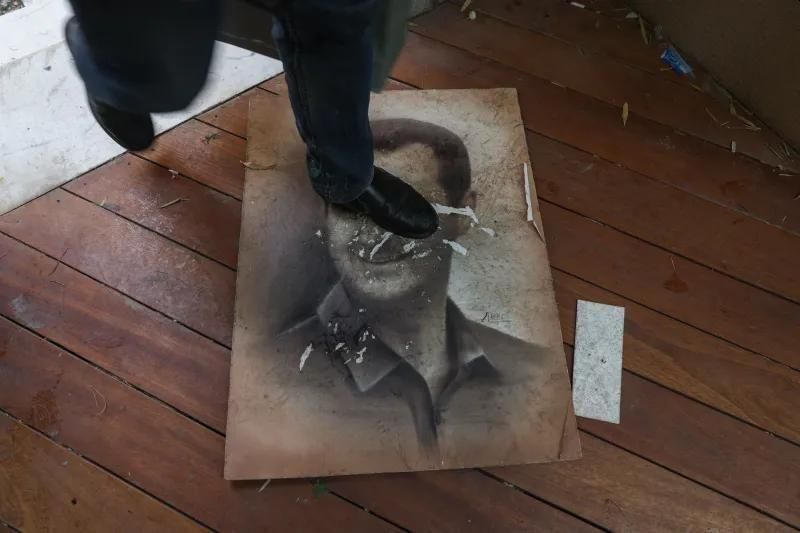

Celebrating the ouster of Syrian President Bashar

al-Assad, Latakia, Syria, December 2024

For updates click hompage here