By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

China Today And Tomorrow

By now, Chinese

President Xi Jinping’s ambition to remake the world is undeniable. He wants to

dissolve Washington’s network of alliances and purge what he dismisses as

“Western” values from international bodies. He wants to knock the U.S. dollar

off its pedestal and eliminate Washington’s chokehold over critical technology.

In his new multipolar order, global institutions and norms will be underpinned

by Chinese notions of common security and economic development, Chinese values

of state-determined political rights, and Chinese technology. China will no

longer have to fight for leadership. Its centrality will be guaranteed.

To hear Xi tell it,

this world is within reach. At the Central Conference on Work Relating to

Foreign Affairs last December, he boasted that Beijing was (in the words of a

government press release) a “confident, self-reliant, open and inclusive major

country,” one that had created the world’s “largest platform for international

cooperation” and led the way in “reforming the international system.” He

asserted that his conception for the global order—a “community with a shared

future for mankind”—had evolved from a “Chinese initiative” to an

“international consensus,” to be realized through the implementation of four

Chinese programs: the Belt and Road

Initiative, the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security

Initiative, and the Global Civilization Initiative.

Outside China,

such brash, self-congratulatory proclamations are generally disregarded or

dismissed—including by American officials, who have tended to discount the

appeal of Beijing’s strategy. It is easy to see why: a large number of China’s

plans appear to be failing or backfiring. Many of China’s neighbors are drawing

closer to Washington, and its economy is faltering. The country’s

confrontational “Wolf Warrior” style of diplomacy may have pleased Xi, but it

won China few friends overseas. Polls indicate that Beijing is broadly

unpopular worldwide: A 2023 Pew Research Center study, for example, surveyed

attitudes toward China and the United States in 24 countries on six continents.

It found that only 28 percent of respondents had a favorable opinion of

Beijing, and just 23 percent said China contributes to global peace. Nearly 60

percent of respondents, by contrast, had a positive view of the United States,

and 61 percent said Washington contributes to peace and stability.

But Xi’s vision is

far more formidable than it seems. China’s proposals would give power to the

many countries that have been frustrated and sidelined by the present order,

but it would still afford the states Washington currently favors valuable

international roles. Beijing’s initiatives are backed by a comprehensive,

well-resourced, and disciplined operational strategy—one that features outreach

to governments and people in seemingly every country. These techniques have

gained Beijing's newfound support, particularly in some multilateral

organizations and from non-democracies. China is succeeding in making itself an

agent of welcome change while portraying the United States as

the defender of a status quo that few particularly like.

Rather than

dismissing Beijing’s playbook, U.S. policymakers should learn from it. To win

what will be a long-term competition, the United States must seize the mantle

of change that China has claimed. Washington needs to articulate and push

forward its vision for a transformed international system and the U.S. role

within that system—one that is inclusive of countries at different economic

levels and with different political systems. Like China, the United States

needs to invest deeply in the technological, military, and diplomatic

foundations that enable both security at home and leadership abroad. Yet as the

country commits to that competition, U.S. policymakers must understand that

near-term stabilization of the bilateral relationship advances rather than

hinders ultimate U.S. objectives. They should build on last year’s summit

between President Joe Biden and Xi, curtailing inflammatory anti-Chinese

rhetoric and creating a more functional diplomatic relationship. That way, the

United States can focus on the more important task: winning the long-term game.

I Can See Clearly Now

Beijing’s playbook

begins with a well-defined vision of a transformed world order. The Chinese

government wants a system built not just on multipolarity but also on absolute

sovereignty; security rooted in international consensus and the UN Charter;

state-determined human rights based on each country’s circumstances;

development as the “master key” to all solutions; the end of U.S. dollar

dominance; and a pledge to leave no country and no one behind. This vision, in

Beijing’s telling, stands in stark contrast to the system the United States

supports. In a 2023 report, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs claimed

Washington was “clinging to the Cold War mentality” and “piecing together small

blocs through its alliance system” to “create division in the region, stoke

confrontation and undermine peace.” The United States, the report continued,

interferes “in the internal affairs of other countries,” uses the dollar’s

status as the international reserve currency to coerce “other countries into

serving America’s political and economic strategy,” and seeks to “deter other

countries’ scientific, technological and economic development.” Finally, the

ministry argued, the United States advances “cultural hegemony.” The “real

weapons in U.S. cultural expansion,” it declared, were the “production lines of

Mattel Company and Coca-Cola.”

Beijing claims that

its vision, by contrast, advances the interests of the majority of the world’s

people. China is center stage, but every country, including the United States,

has a role to play. At the 2024 Munich Security Conference in February, for example,

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China and the United States are

responsible for global strategic stability. China and Russia, meanwhile,

represent the exploration of a new model for major-country relations. China and

the European Union are the world’s two major markets and civilizations and

should resist establishing blocs based on ideology. And China, as what Wang

called the “largest developing country,” promotes solidarity and cooperation

with the global South to increase its representation in global affairs.

China’s vision is

designed to be compelling for nearly all countries. Those that are not

democracies will have their choices validated. Those that are democracies but

not major powers will gain a greater voice in the international system and a

bigger share of the benefits of globalization. Even the major democratic powers

can reflect on whether the current system is adequate for meeting today’s

challenges or whether China has something better to offer. Observers in the

United States and elsewhere may roll their eyes at the grandiose phrasing, but

they do so at their peril: dissatisfaction with the current international order

has created a global audience more amenable to China’s proposals than might

have existed not long ago.

Four Pillars

For over two decades,

China has referred to a “new security concept” that embraces norms such as

common security, system diversity, and multipolarity. But in recent years,

China believes it has acquired the capability to advance its vision. To that

end, during his first decade in power, Xi released three distinct global

programs: the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, the Global Development

Initiative (GDI) in 2021, and the Global Security Initiative (GSI) in 2022.

Each contributes in some way to furthering both the transformation of the

international system and China’s centrality within it.

The BRI was initially

a platform for Beijing to address the hard infrastructure needs of emerging and

middle-income economies while making use of the Chinese construction industry’s

overcapacity. It has since expanded to become an engine of Beijing’s geostrategy:

embedding China’s digital, health, and clean technology ecosystems globally;

promoting its development model; expanding the reach of its military and police

forces; and advancing the use of its currency.

The GDI focuses on

global development more broadly, and it places China squarely in the driver’s

seat. Often working with the UN, it supports small-scale projects that address

poverty alleviation, digital connectivity, climate change, and health and food

security. It advances Beijing’s preference for economic development as a

foundation for human rights. One government document on the program, for

instance, accuses other countries of the “marginalization of development issues

by emphasizing human rights and democracy.”

Beijing has

positioned the GSI as a system for, as several Chinese scholars have put it,

providing “Chinese wisdom and Chinese solutions” to promote “world peace and

tranquility.” In Xi’s words, the GSI advocates that countries “reject the Cold

War mentality, oppose unilateralism, and say no to group politics and bloc

confrontation.” The better course, according to Xi, entails building a

“balanced, effective and sustainable security architecture” that resolves

differences between countries through dialogue and consultation and that

upholds noninterference in others’ internal affairs. Behind the rhetoric, the

GSI is designed to end U.S. alliance systems, establish security as a

precondition for development, and promote absolute sovereignty and indivisible

security—or the notion that one state’s safety should not come at the expense

of others’. China and Russia have used this notion to justify Russia’s invasion

of Ukraine, suggesting that Moscow’s attack was needed to stop an expanding

NATO from threatening Russia.

But Xi’s strategy has

taken flight only in the past year, with the release of the Global Civilization

Initiative in May 2023. The GCI advances the idea that countries with different

civilizations and levels of development will have different political and

economic models. It asserts that states determine rights and that no one

country or model has a mandate to control the discourse of human rights. As

former Foreign Minister Qin Gang put it: “There is no one-size-fits-all model

in the protection of human rights.” Thus, Greece, with its philosophical and

cultural traditions and level of development, may have a different conception

and practice of human rights than China does. Both are equally valid.

Chinese leaders are

working hard to get countries and international institutions to buy into their

world vision. Their strategy is multilevel: striking deals with individual

countries, integrating their initiatives or components of them into

multilateral organizations, and embedding their proposals into global

governance institutions. The BRI is the model for this approach. Around 150

countries have become members of the program, which openly advocates for the

values that frame China’s vision—such as the primacy of development,

sovereignty, state-directed political rights, and common security. This

bilateral dealmaking has been accompanied by Chinese officials’ efforts to link

the BRI to other regional development efforts, such as the Master Plan on

Connectivity 2025 created by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations

(ASEAN).

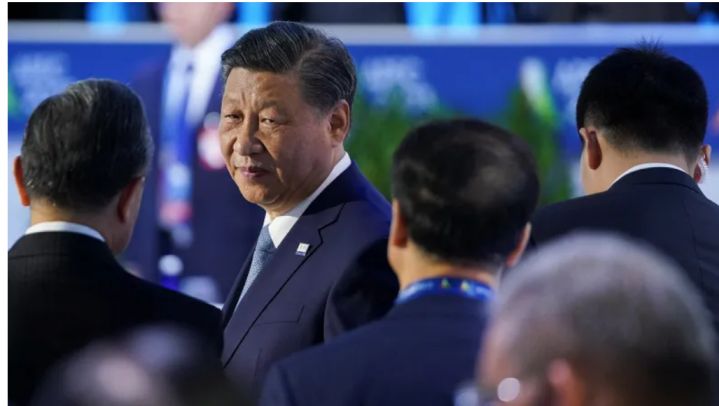

Xi at a summit in San Francisco, November 2023

China has also

successfully embedded the BRI in more than two dozen UN agencies and programs.

It has worked particularly diligently to align the BRI and the UN’s

high-profile 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The UN Department of

Economic and Social Affairs, which has been headed by a Chinese official for

over a decade, produced a report on the BRI’s support for the agenda. The

report was partially funded by the UN Peace and Development Trust Fund, which,

in turn, was initially established by a $200 million Chinese pledge. Such

support undoubtedly contributes to the enthusiasm many senior UN officials,

including the secretary-general, have shown for the BRI.

Progress on the GDI,

GSI, and GCI has understandably been more nascent. Thus far, only a handful of

leaders from countries such as Serbia, South Africa, South Sudan, and Venezuela

have offered rhetorical support for the GCI’s notion that the diversity of

civilizations and development paths should be respected—and by extension, for

China’s vision for an order that does not give primacy to the values of liberal

democracies.

The GDI has gained

more international support than the GCI. After Xi announced the project before

the UN General Assembly, China developed a “Group of Friends of the GDI” that

now boasts more than 70 countries. The GDI has advanced 50 projects and pledged

100,000 training opportunities for officials and experts from other countries

to travel to China and study its systems. These training opportunities are

designed to promote China’s advanced technologies, its management experiences,

and its development model. China has also succeeded in formally linking the GDI

to the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and held GDI-related

seminars with the UN Office for South-South Cooperation. Beijing, in other

words, is weaving the program into the fabric of the international governmental

system.

The GSI has achieved

even greater rhetorical buy-in. According to China’s Foreign Ministry, more

than 100 countries, regional organizations, and international organizations

have supported the GSI, and Chinese officials have encouraged the BRICS

(Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), ASEAN, and the Shanghai

Cooperation Organization to adopt the concept. At the SCO’s September 2022

meeting, China advanced the GSI and received support from all the members

except India and Tajikistan.

Mass Appeal

China, in contrast

with the United States, invests heavily in the diplomatic resources necessary

to market its initiatives. It has more embassies and representative offices

around the globe than any other country, and Chinese diplomats frequently speak

at conferences and publish a stream of articles about China’s various

initiatives in local news outlets.

This diplomatic

apparatus is supported by equally sprawling Chinese media networks. China’s

international news network, CGTN, has twice as many overseas bureaus as CNN,

and Xinhua, the official Chinese news service, has over 180 bureaus globally.

Although Chinese media are often perceived in the West as little more than

crude propaganda tools, they can advance a positive image of China and its

leadership. In a study published in 2024, a team of international scholars

surveyed more than 6,000 respondents in 19 countries to see whether China or

the United States was more effective at selling its political and economic

model and its role as a global leader. At baseline, participants overwhelmingly

preferred the United States—83 percent of the interviewees preferred the U.S.

political model, 70 percent preferred the U.S. economic model, and 78 percent

preferred U.S. leadership. But when they were exposed to Chinese media

messaging—whether only to China’s or to Chinese and U.S. government messaging

in a head-to-head competition—participants preferred the Chinese models to

those of the United States.

Beijing also draws

heavily on the strength of state-owned companies and the country’s private

sector to promote its objectives. China’s technology firms, for instance, not

only provide digital connectivity to a variety of countries; they also enable

states to emulate elements of Beijing’s political model. According to Freedom

House, representatives from 36 countries have participated in Chinese

government training sessions on how to control media and information on the

Internet. In Zambia, adopting a “China way” for Internet governance—as a former

government minister described it—resulted in the imprisonment of several

Zambians for criticizing the president online. German Council on Foreign

Relations experts revealed that Huawei middleboxes blocked websites in 17

countries. The more states adopt Chinese norms and technologies that suppress

political and civil liberties, the more Beijing can undermine the current

international system’s embrace of universal human rights.

In addition, Xi has

enhanced the role of China’s security apparatus as a diplomatic tool. China’s

People’s Liberation Army is conducting exercises with a growing number of

countries and offering training to militaries throughout the developing world.

Last year, for example, China brought more than 100 senior military officials

from almost 50 African countries and the African Union to Beijing for the third

China-Africa Peace and Security Forum. China and the African participants

agreed to hold more joint military exercises, and they embraced the BRI and the

GSI, alongside the African Union’s Agenda 2063 development plan, as a way to

pursue economic development, promote peace, and ensure stability on the

continent. Together, these arrangements help create the collaborative security

system China wants: one that’s based on Beijing.

China has boosted its

strategy by being both patient and opportunistic. Beijing provides massive

resources for its initiatives, reassuring other countries of its long-term

support and enabling Chinese officials to act quickly when opportunities arise.

For example, Beijing first announced a version of the Health Silk Road in 2015,

but it garnered little attention. In 2020, however, China used the COVID-19

pandemic to breathe new life into the project. Xi delivered a major address

before the World Health Assembly promoting China as a hub for medical

resources. Beijing paired Chinese provinces with different countries and had

the former send personal protective equipment and medical professionals to the

latter. China also used the pandemic to push Chinese digital health

technologies and traditional Chinese medicine—a priority for Xi—as ways to

treat the virus.

More recently, China

has used Russia’s and the resulting Western sanctions to push de-dollarizing

the global economy. China’s trade with Russia is

now mostly settled in renminbi, and Beijing is working through the BRI and

multilateral organizations, such as the BRICS (which 34 countries have

expressed interest in joining), to advance de-dollarization. As Brazilian

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said during a 2023 visit to China, “Every

night I ask myself why all countries have to base their trade on the dollar.

Why can’t we do trade based on our currencies?”

The Payoff

Beijing has made

progress in gaining rhetorical buy-in from other countries, as well as from UN

organizations and officials. But in terms of effecting actual change on the

ground, garnering support from other countries’ citizens, and influencing the

reform of international institutions, China’s record is more mixed.

The GDI, for its

part, is well on its way. A two-year progress report produced by the Xinhua

News Agency’s think tank indicated that 20 percent of the GDI’s initial 50

cooperation programs had been completed, and an additional 200 had been

proposed. Some projects are highly local and long-term, but others will have a

greater immediate impact, such as a wind power project in Kazakhstan that will

meet the energy needs of more than one million households.

Despite the relative

nascence of the GSI, Wang, China’s foreign minister, quickly claimed that the

Beijing-brokered 2023 rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia was an

example of the GSI’s principle of promoting dialogue. China has had less

success, however, using GSI principles in its attempts to resolve the war in

Ukraine and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Moreover, some countries

have expressed concern that the GSI is a kind of military alliance. Despite

being an early beneficiary of GDI projects, for example, Nepal has resisted

multiple Chinese entreaties to join the GSI because it does not want to be part

of any security alliance.

The BRI has

transformed the geostrategic and economic landscape throughout much of Africa,

Southeast Asia, and, increasingly, Latin America. Huawei, for example, provides

70 percent of all the components in Africa’s 4G telecommunications

infrastructure. In addition, China’s 2023 BRI investments have increased from

2022. There are signs, however, that the BRI’s influence may be plateauing.

Italy, the biggest economy in the initiative (aside from China itself),

withdrew in December, and only 23 leaders attended the 2023 Belt and Road

Forum, compared with 37 in 2019. China’s financing for the BRI has fallen

sharply since its peak in 2016, and many BRI recipient countries are struggling

to repay Beijing’s loans.

A screen broadcasting an air force drill, Beijing,

August 2023

Public opinion polls

paint a similarly mixed picture. The Pew poll indicated that middle-income

economies, particularly in Africa and Latin America, are more likely to have

positive views of China and its contributions to stability than higher-income

economies in Asia and Europe. But even in these regions, popular views of China

are far from uniformly positive.

A 2023 survey of

1,308 elites in ASEAN states, for instance, reveals that although China is

considered the most influential economic and security actor in the region,

majorities in every country, except Brunei, express concern over China’s rising

influence. Pluralities or majorities in seven of ten countries do not believe

that the GSI will benefit their region. And when asked whether they would align

with China or with the United States if forced to choose, majorities in seven

of ten ASEAN countries selected the United States.

Afrobarometer’s 2019

and 2020 surveys suggest China has a more positive reputation in Africa: 63

percent of Africans polled in 34 countries believe China is a positive external

influence. But only 22 percent believe China is the best model for future development,

and approval of China’s model declined from the 2014 and 2015 surveys.

A 2021 survey of 336

opinion leaders from 23 countries in Latin America was similarly telling.

Although 78 percent of respondents believe China’s overall influence in the

region is high, only 35 percent have a good or very good opinion of China.

(Respondents have similar opinions about the United States.) There was support

for engagement with China on trade and foreign direct investment but minimal

support for engagement on multilateral cooperation, international security, and

human rights.

Finally, support for

China and Chinese-backed initiatives in the United Nations is mixed. For

example, a detailed study of China’s Digital Silk Road investment in Africa

found that although eight African DSR members supported China’s New IP proposal

for increasing state control over the Internet, more African DSR members did

not write in support of it. And the February 2023 vote to condemn Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine—in which 141 countries voted in favor, seven voted against,

and 32, including China and all other members of the SCO except Russia,

abstained—suggests widespread rejection of the GSI’s principle of indivisible

security. Nonetheless, China won the support of 25 of the 31 emerging and

middle-income countries (not including itself) in the UN Human Rights Council

in a successful bid to prevent debate on Beijing’s treatment of its Uyghur

minority population. It was only the second time in the council’s history that

a debate has been blocked.

Fighting Fire With Fire

Support for China’s

efforts may appear shallow among many segments of the international community.

But China’s leaders express great confidence in their transformative vision,

and there is significant momentum behind the basic principles and policies proposed

in the GDI, GSI, and GCI among members of BRICS and the SCO, as well as among

nondemocracies and African countries. China’s wins within bigger

organizations—such as the UN—may seem minor, but they are accumulating, giving

Beijing substantial authority inside major institutions that many emerging and

middle-income economies value. And Beijing has a formidable operational

strategy for achieving its desired transformation, along with the capability to

coordinate policy at multiple levels of government over a long period.

Part of why Beijing’s

efforts are catching on is that the present, U.S.-led system is unpopular in

much of the world. It does not have a good record of meeting global challenges

such as pandemics, climate change, debt crises, or food shortages—all of which

disproportionately affect the planet’s most vulnerable people. Many countries

believe that the United Nations and its institutions, including the Security

Council, do not adequately reflect the world’s distribution of power. The

international system has also not proved capable of resolving long-standing

conflicts or preventing new ones. And the United States is increasingly viewed

as operating outside the very institutions and norms it helped create:

deploying widespread sanctions without Security Council approval, helping

weaken international bodies such as the World Trade Organization, and, during

the Trump administration, withdrawing from global agreements. Finally,

Washington’s periodic framing of the world system as one divided between

autocracies and democracies alienates many countries, including some democratic

ones.

Even if its vision is

not fully realized, unless the world has a credible alternative, China can take

advantage of this dissatisfaction to make significant progress in materially

degrading the current international system. The uphill battle the United States

has waged to persuade countries to avoid Huawei telecommunications equipment is

an important lesson in addressing a problem before it arises. It would be far

more difficult to overturn a global order that has devalued universal human

rights in favor of state-determined rights, significantly de-dollarized the

financial system, widely embedded state-controlled technology systems, and

deconstructed U.S.-led military alliances.

The United States

should therefore move aggressively to position itself as a force for system

change. It should take a page from China’s playbook and be

opportunistic—seeking strategic advantage as China’s economy is faltering and

its political system is under stress. It should acknowledge that, as Xi has

repeatedly said, there are changes in the world “the likes of which we haven’t

seen for 100 years” but make clear that these shifts do not signal the decline

of the United States. Instead, they are in line with Washington’s own dynamic

vision for the future.

The vision should

begin by advancing an economic and technological revolution that will transform

the world’s digital, energy, agricultural, and health landscapes in ways that

are inclusive and contribute to shared global prosperity. This will require new

norms and institutions that integrate emerging and middle-income economies into

resilient and diversified global supply chains, innovation networks, clean

manufacturing ecosystems, and information and data governance regimes.

Washington should promote a global conversation on its vision of

technologically advanced change rooted in high standards, the rule of law,

transparency, official accountability, and sustainability—norms of shared good

governance that are not ideologically laden. Such a discussion would likely be

widely popular, just as China’s focus on the imperative of development holds

broad appeal.

Washington has put in

place some of the building blocks of this vision through the U.S.-EU Trade and

Technology Council, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, and the Partnership

for Global Infrastructure Investment. Largely left out of the equation, however,

are precisely the states most open to China’s vision of transformation—most

members of the BRICS, the SCO, and nondemocratic emerging and middle-income

economies. Together with these countries, Washington should explore regional

arrangements akin to those it has established with its Asian and European

partners. More countries should be brought into the networks Washington is

establishing to build stronger supply chains, such as those created by the

CHIPS and Science Act. And countries such as Cambodia and Laos, left out of

relevant existing arrangements such as the Indo-Pacific framework, should be

given a path to membership. This would expand the United States’ development

footprint, allowing it to provide a development trajectory that is different from

Beijing’s BRI and GDI and—unlike China’s initiatives—offers participating

countries an opportunity to help develop the rules of the road.

Artificial

intelligence presents

a unique opportunity for the United States to signal a new, more inclusive

approach. As its full applications become appreciated, AI will require new

international norms and potentially new institutions to harness its positive

effects and limit its negative ones. The United States, which is the world’s

leading AI innovator, should engage upfront with countries other than its

traditional allies and partners to develop regulations. Joint U.S.-EU efforts

regarding skills training for the next generation of AI jobs, for example,

should be expanded to include the global majority. The United States can also

support engagement between its robust private sector and civil society

organizations and their counterparts in other countries—a multistakeholder approach

that China, with its “head of state” style of diplomacy, typically eschews.

This effort will

require Washington to draw more effectively on the U.S. private sector and

civil society—much as China has worked its state-owned enterprises and private

sector into the BRI and GDI—by fostering vibrant, state-initiated but

business-and-civil-society-driven international partnerships. In most of the

world, including Africa and Latin America, the United States is a larger and

more desired source of foreign direct investment and assistance than China. And

Washington has left untapped a significant alignment of interests between its

strategic goals and the economic objectives of the private sector, such as

creating political and economic environments abroad that enable U.S. companies

to flourish. Because American companies and foundations are private actors,

however, the benefits of their investments do not redound to the U.S.

government. Institutionalizing public-private partnerships can better link U.S.

objectives with the strength of the American private sector and help ensure

that initiatives are not cast aside during political transitions in Washington.

The work of private foundations in the United States—which invest billions of

dollars in emerging economies and middle-income countries—should similarly be

amplified by American officials and lifted up through partnerships with

Washington.

More inclusive global

governance also requires that Washington consider potential tradeoffs as other

countries’ economies and militaries grow relative to those of the United

States. In the near term, for example, a clearer delineation of the limits of

U.S. sanctions policy could help slow the momentum behind Beijing’s

de-dollarization effort. But Washington should use this time to assess the

viability of the dollar’s dominance over the longer term and consider what

steps, if any, U.S. officials should take to try to preserve it. Washington’s

vision may also need to incorporate reforms to the current alliance system. The

hard realities of China’s growing military prowess and its economic support for

Russia during the latter’s war against Ukraine make clear that Washington and

its allies must think anew about the security structures necessary to manage a

world in which Beijing and its like-minded partners operate as soft, and

potentially hard, military allies.

As with China, the

United States needs to spend more on the foundations of its competitiveness and

national security to succeed over the long term. Although defensive policies

are often necessary, they grant only short-term protections. This means Washington

must staff up to match Beijing’s foreign policy apparatus. Around 30 U.S.

embassies and missions have no sitting U.S. ambassador; each of these slots

must be filled. The United States has taken the first steps to enhance its

economic competitiveness with programs such as the Inflation Reduction Act and

the CHIPS and Science Act, but it needs sustained investment in research and

development and advanced manufacturing. It also needs to adopt immigration

policies that attract and retain top talent from around the world. And

Washington needs to recommit to investing in the foundations of its long-term

military capabilities and modernization. Without bipartisan support for the

basic building blocks of American competitiveness and global leadership,

Beijing will continue to make headway in changing the global order.

Finally, to avoid

unnecessary friction, the United States should continue to stabilize the

U.S.-Chinese relationship by defining new areas for cooperation, expanding

civil society engagement, tamping down needless hostile rhetoric, strategically

managing its Taiwan policy, and developing a clear message on the economic

tools it uses to protect U.S. economic and national security. This will enable

the United States to maintain relations with those in China who are concerned

about their country’s current trajectory, as well as give Washington room to

focus on building up its economic and military capabilities while moving

forward with its global vision.

China is right: the

international system does need reform. But the foundations for that reform are

best found in the openness, transparency, rule of law, and official

accountability that are the hallmarks of the world’s market democracies. The The global innovation and creativity necessary to solve the

world’s challenges thrive best in open societies. Transparency, the rule of

law, and official accountability are the foundation of healthy, sustained

global economic growth. The current system of alliances, although insufficient

to ensure global peace and security, has helped prevent war from breaking out

among the world’s great powers for more than 70 years. China has not yet

managed to convince a majority of the planet’s people that its intentions and

capabilities are the ones needed to shape the twenty-first century. But it is

up to the United States and its allies and partners to create an affirmative

and compelling alternative.

For updates click hompage here