By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

How The World Can Deal With Trump's

Advice

In this year of major

elections around the world, none is more consequential than that in the United

States on the first Tuesday in November. Polling suggests Donald Trump will

enter the White House again in January 2025. If he does, he will return to

office perhaps no wiser but certainly more experienced and more convinced than

ever of his exceptional genius. More ominously, he will be determined to

rectify in his second term what he insists was the major failing of his first:

that both his advisers and Washington officialdom got in his way.

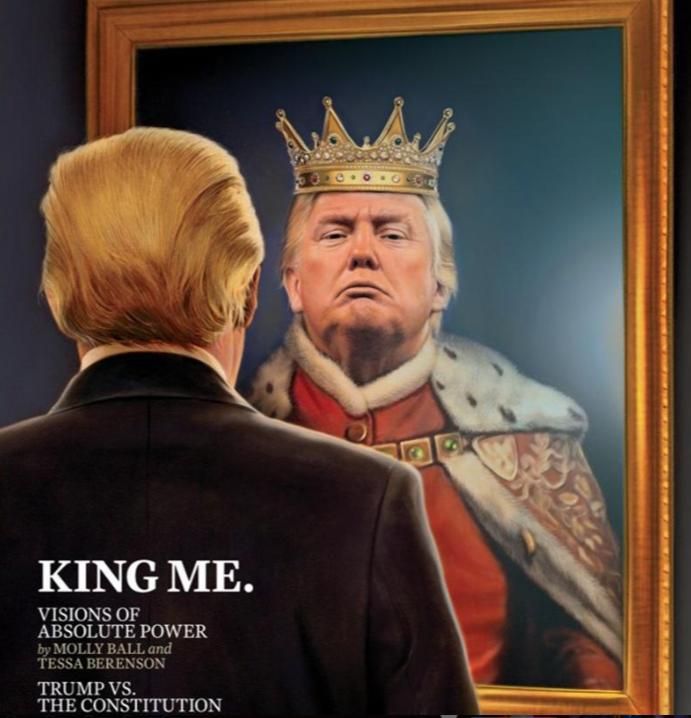

Like most

people, Trump is often wrong. Unlike most people, however, he is

never in doubt. A powerful narcissistic self-belief has given him the strength

to defy not just his many enemies but even reality itself. For four years, he

has denied the outcome of the 2020 election and persuaded most of his party,

and millions of Americans, to agree with him. There has never been such an

effective and relentless gaslighter.

As president, he

sought to surround himself with people who told him what he wanted to hear.

When they stopped doing so, they were quickly sent packing. If Trump returns to

the Oval Office, his instinct to crush critics and stack the executive branch

with yes men will likely get even stronger. He will characterize his domestic

critics as political opponents if they are Democrats and as traitors if they

are Republicans. Trump will feel invincible in his triumph as a Roman emperor,

but he won’t have a slave by his side whispering, “Remember, you are mortal.”

Other leaders,

especially those of countries that are close U.S. allies, have an opportunity

and a responsibility to speak to Trump with a blunt but respectful candor that

few of his advisers will be able to offer him. Around the world, leaders are

once again fretting about how they can flatter Trump and avoid his wrath. But

that pliant approach is not just the wrong strategy; it is the last thing

the United States needs.

A New Normal

After Trump became

president in 2017, most leaders around the world found themselves laboring

under two incorrect assumptions. The first was that Trump’s wild rhetoric on

the campaign trail would be abandoned there. The office and its

responsibilities, some leaders believed, would constrain him. In November 2016,

a few weeks after Trump’s surprising victory, the leaders of many of the

world’s largest economies met in Lima at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

summit. It was Barack Obama’s last summit as U.S. president, but it was

Trump who overshadowed the whole APEC conference. By way of reassurance, many

quoted former New York Governor Mario Cuomo’s remark: “You campaign in poetry.

You govern in prose.” The line was repeated so often that a frustrated

President Michelle Bachelet of Chile observed wryly that she had not seen many

signs of poetry in the campaign that had just ended.

Many leaders expected

that Trump would become more typically “presidential” once he entered the White

House. That was certainly the view held by Chinese President Xi Jinping.

He told me at the APEC summit that he was relaxed about the new U.S. president.

Xi thought Trump’s campaign rhetoric would have no bearing on how he would

govern, and most significantly, the Chinese president believed the U.S. system

would not allow Trump to act in a way that undermined the American national

interest.

And that was

generally the consensus view: the institutions of government would keep Trump

grounded in a conventional, administrative reality. His colorful campaign would

be followed by business, more or less, as usual.

Trump in office was,

if anything, wilder and more erratic than he had been on the campaign trail.

Four extraordinary years finished with him encouraging a mob to storm the U.S.

Capitol in a brazen attempt to overthrow the constitutional transfer of power

to the new president. If Trump returns to the White House in 2025, only the

willfully deluded could imagine that a second Trump administration would be

less volatile and alarming than the first.

Don’t Give In

The second

misapprehension world leaders held was that the right way to deal with Trump

was how Benjamin Disraeli, the nineteenth-century British prime minister,

advised people to deal with royalty: to use flattery and “lay it on with a

trowel.” Of course, men like Trump invite sycophancy. They use their power and

caprice to encourage others to tell them what they want to hear. But this is

precisely the wrong way to deal with Trump, or any other bully. Whether in the

Oval Office or on the playground, giving in to bullies encourages more

bullying. The only way to win the respect of people such as Trump is to stand

up to them.

But that defiance

brings with it great risks. Almost all world leaders hope to have a good, or at

least cordial, relationship with the United States. And they know that if they

have a falling out with the U.S. president, there is no guarantee that their own

people, let alone their own media, would take their side. This is particularly

so in countries where a right-wing, so-called conservative media generally

support Trump and his style of politics. Trump’s biggest echo chamber in the

United States is the Fox News network, owned by Rupert Murdoch, who also

controls extensive media assets in Australia and the United Kingdom.

The Potential Australia Trade Wars

In 2016, an agreement

with Obama was reached that several asylum seekers who had sought to

enter Australia irregularly by boat could be settled in the United

States, subject to the usual security vetting. Australia had learned over the

years that the only way to stop human smuggling was to ensure that nobody who

came unlawfully by boat could settle in our country. This policy had been

strictly applied under Liberal Prime Minister John Howard, who held the office

from 1996 to 2007 but was modified under his Labor successors Kevin Rudd and

Julia Gillard. The result was a dramatic increase in human smuggling. When Rudd

returned as prime minister for a few months, in late 2013, he tried to

reinstate the Howard-era policies, and as a consequence, several thousand

asylum seekers were intercepted and detained in Papua New Guinea and Nauru.

The Liberals returned

to government in October 2013 under Tony Abbott. Most governments have followed

a strict zero-tolerance approach to human smuggling. And it has worked. But

there were still the asylum seekers who had been diverted to Papua New Guinea

and Nauru. If they were brought to Australia, there was a fear that the flow of

boats would start up again. So the deal with Obama was a practical and humane

solution. In return, Australia had agreed to accept some very difficult

immigration cases for the United States.

Trump made it clear

that he was proceeding with the deal unhappily. But he also accepted, as I had

suggested, that he could honor the deal his predecessor had made without

endorsing it as a good one. Details of the call were leaked in Washington,

eventually with a transcript, all designed to show that Trump went along with

the deal with reluctance.

There was enormous

anxiety in Canberra about how their deal with Trump would play out. Would he

honor the deal? As it turned out, he did. Would this row adversely affect other

aspects of the relationship? And most important, would Trump bear a grudge?

Make The Case

Most presidents and

prime ministers delegate considerable authority, formally and informally, to

their advisers and officials. Meetings with foreign leaders are negotiated well

in advance by ambassadors and officials. The outcome of the meeting is as scripted

as the talking points.

The Trump White House

did not work like that. Trump was the only decision-maker. Staff could advise

him however they pleased, but most didn’t last long anyway. The only word that

mattered was Trump’s, and he did not like being scripted—in any event, he rarely

read from the script. He was the dealmaker, so he wanted to do the deal, on the

spot, in the room.

For Trump, this meant

that ambassadors and foreign ministers, no matter how capable, could offer much

less assistance or influence. The key relationship lay between Trump and the

foreign leader.

This practice poses

both a challenge and an opportunity for foreign leaders trying to gain traction

in the White House. It means that their ambassadors are less influential. On

the other hand, if it is possible to persuade Trump that it is in his interest

to change course, he will. But to do that, a foreign leader has to win Trump’s

respect and make a strong case.

In March 2018, Trump

announced he was going to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum imports of 25

percent and 10 percent, respectively. Not only was Trump keen on these tariffs,

but so were some of his key advisers, including Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross

and Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer.

Turnbull and Trump in Washington, D.C., February 2018

Trump’s views on trade

were simplistic. But they were strongly held. He viewed a trade deficit as

evidence that the United States was losing and a trade surplus as a sign it was

winning. He gave Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe a hard time on the U.S.

trade deficit with Japan, as he did other allied leaders, but his greatest

anxiety was the huge trade deficit with China.

A 25 percent tariff

on Australian steel would not make U.S. steel more competitive on the West

Coast; it would simply raise the price of steel roofs. We went through the

numbers several times. He knew the building industry, and he knew the product,

and he listened more attentively than usual.

Second, if Trump’s argument

for tariffs was to correct trade terms with other countries that were not fair

and reciprocal, why should he impose any tariff on Australian exports?

Australia and the United States had maintained a free trade agreement for

years. The United States also enjoyed a large trade surplus with

Australia.

If the United States

imposed tariffs or an import quota on Australia, with whom it had the best

possible trade deal, it would be seen as doing so simply because it could.

Speaking Truth To Trump

The caricature of

Trump as a one-dimensional, irrational monster is so entrenched that many

forget that he can be, when it suits him, intelligently transactional. Like

most bullies, he will bend others to his will when he can, and when he cannot,

he will try to make a deal. But to get to the deal-making stage, Trump’s

counterparts have to stand up to the bullying first.

Foreign leaders who

need to get business done with Trump should be able to do so, but they will

need to deal with him directly and persuade him why their proposal is a good

deal for him. Leave the sentimental stuff about alliances and friendship for

the press conferences. Trump’s question is always, “What’s in it for me?” His

calculus is both political and commercial, but it is very focused. That should

be no surprise—“America first” is his explicit slogan.

A Trump returned to

the White House, convinced of his genius, and with the evidence of an election

win to prove it, will be surrounded by more yes men and sycophants than ever.

In that environment, who will be prepared to tell him what he doesn’t want to

hear?

The leaders of the

countries that are the United States’ friends and allies will be among the very

few who can speak truthfully to Trump. He can shout at them, embarrass them,

even threaten them. But he cannot fire them. Their character, courage, and candor

may be the most important aid they can render to the United States in a second

age of Trump.

For updates click hompage here