By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Russia

And Turkey Today

Russia and Turkey’s

complex relationship sometimes baffles outside observers. Turkey and Russia are

fierce competitors in many respects: Moscow and Ankara back opposing camps in

Libya, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh, and Turkey is a member of NATO – the

alliance Russia views as both adversary and threat. Nevertheless, this has not

prevented collaboration between the two powers, who share profound economic and

cultural ties and have made concerted efforts to deepen diplomatic relations,

often to the frustration of Turkey’s Western allies.

But 2022 has been a

year of unprecedented trade growth between the two countries – the only NATO

member yet to participate in anti-Russia sanctions. The government in Ankara

has made it a point to keep a constant dialogue with Moscow on various issues.

But that doesn’t change the fact that Russia and Turkey are natural competitors

with strict limits to the level of cooperation they can engage in. Still, a

long-term partnership, however, constrained, is acceptable to both so long as

everyone, including European countries, benefits from the relationship.

A Lot Of Sense

Russia’s interests

have long intersected with Turkey’s. This presents as many opportunities for

conflict as it does for cooperation. Turkey and Russia see each other as

neighbors along the Black Sea, and both are interested in maintaining good

relations while keeping a certain distance. Tensions arise, of course, in

places like the Caucasus, which both see as their backyard.

Today, their

interests butt against each other in several areas. Take Central Asia. The

region boasts predominantly Muslim but ethnically Turkic populations, and

Ankara has engaged in several projects to shore up its ethnic linkages. Moscow

believes Ankara is doing so in its traditional buffer zone and sphere of

influence. In the Middle East, they are on opposite sides of the Syrian war. In

the Caucasus, Turkey actively supports Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh

conflict, even as Russia balances between Azerbaijan and Armenia. In Ukraine,

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan entered into a strategic military and

political alliance with Kyiv at the outset of the war, sending drones and

helping to build out the Ukrainian navy.

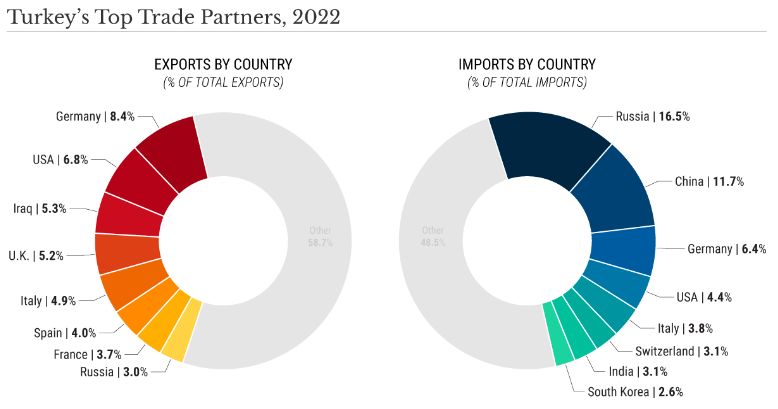

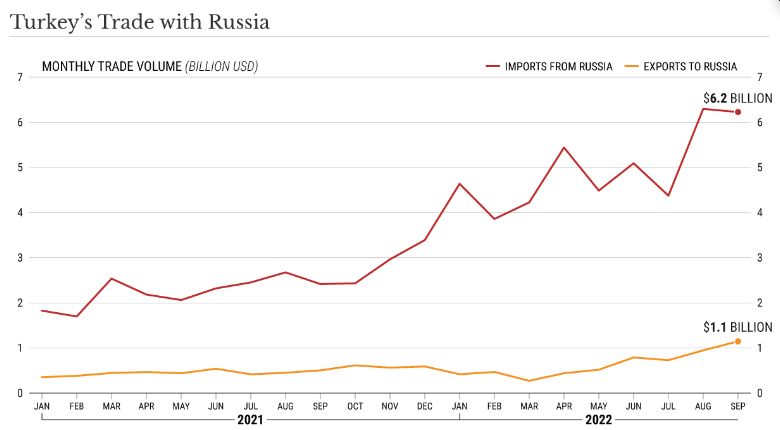

Despite all their

differences, they have benefited from improved trade relations this year. They

recorded growth in key areas such as engineering products, civil electronics,

and food products. In August, Moscow and Ankara signed a roadmap for economic

cooperation to increase trade to $100 billion annually. The fact that the

Russian ruble is legally accepted in Turkey has facilitated this newfound

partnership. In September, Russian authorities announced that Turkey would

start paying for 25 percent of Russian gas supplies in rubles. On Oct. 12,

Russian President Vladimir Putin proposed the creation of a gas hub in Turkey,

which could offset Russian losses through the Nord Stream pipeline and to which

the Turkish government has been very receptive.

And though this may

seem like a contradictory turn of events, it makes sense for both. Bilateral

relations between Russia and Turkey are built primarily on the pursuit of

economic imperatives. Both economies have structural problems generally, and

both were in particularly bad shape earlier this year, thanks to the COVID-19

pandemic, supply chain disruptions, and so on. Sanctions made Russia’s problems

only direr.

Moscow needs to

constantly export energy resources to ensure the inflow of funds and replenish

the budget. It also needs to maintain access to imports to ensure the influx of

consumer goods and products on which Russia remains import-dependent. This has

been particularly tricky without access to the SWIFT payment system. For its

part, the Turkish economy is in crisis – on the eve of elections, no less. The

Turkish lira continues to weaken, with inflation getting worse. The central

bank systematically reduces key interest rates, lowering the cost of loans to

increase business activity but strengthening exporters' position vis-a-vis the

lira. Turkey's economic model is based on production, which is also stimulated

by cheap credit – and on exports to avoid overproduction and recession and ensure

the inflow of foreign currency. In this model, Turkey needs to have a permanent

trading partner, and Russia, which is struggling to produce industrial products

on its own – things that Turkey can produce – is a natural partner.

Importantly, Turkey depends on Russian energy resources, so it would have a

hard time saying no to Russian trade proposals even if it wanted to.

Third parties benefit

from Turkish-Russian cooperation, too, largely because Turkey’s

location makes it an ideal transit hub. The European Union, for example,

was an important trade partner for Russia, but much of its trade has dried up

because of sanctions. Under these conditions, Turkey becomes a waypoint for the

transit of goods to Russia and a re-exporter of goods like Russian gas. Hence,

Turkish imports from Italy, Germany, France, and the U.S. have increased.

Still, there’s no

reason to believe this will be a lasting marriage. Put, there are major

geopolitical obstacles that stand in the way. Russia has always been active in

the Black Sea, and its activities will always be seen by Turkey, to some degree

or another, as an encroachment. Ankara believes Russian behavior – be it the

war in Ukraine, the incursion into the breakaway Georgian territory of

Abkhazia, or the annexation of Crimea – can tip the balance of regional power

in Russia's favor, and thus wants to try to counter Moscow when it believes its

interests are under threat. Russia sees Turkish forays in the Caucasus and

Central Asia similarly. None of this is prohibitive for cooperation, of course.

Still, both sides understand that they are working within a set of geopolitical

parameters rather than acting on opportunities with limitless potential.

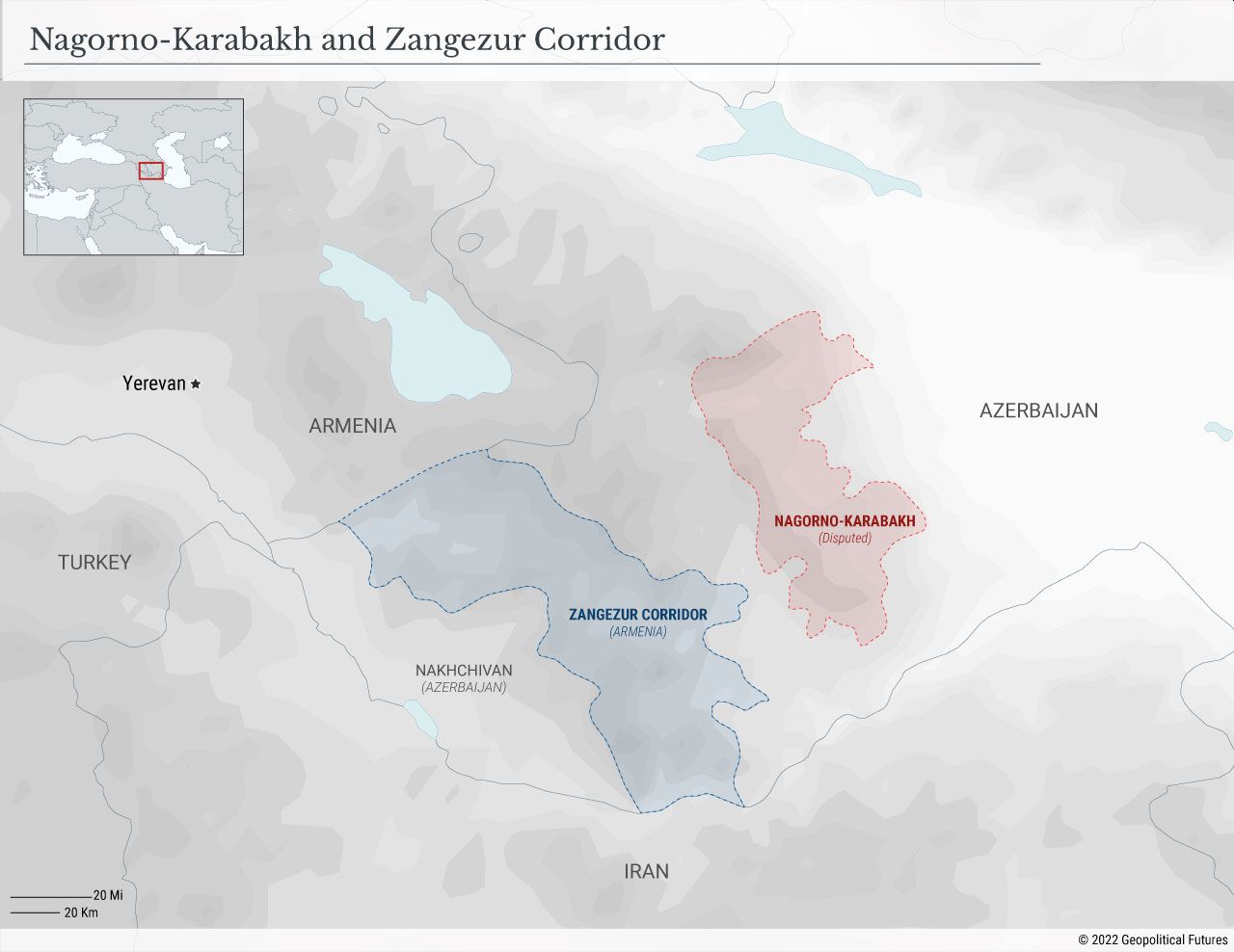

There are also

practical considerations that hamper relations. Because of logistics,

infrastructure, and supply and demand, there is only so much trade they can do

with each other. Turkish transportation is carried out by sea, and the war in

Ukraine has stymied transportation via the Black Sea. Turkey is actively

working on new ways to deliver goods, but traffic, chokepoints, and other

regional conflicts have complicated its efforts. (Turkey was particularly

interested in the Zangezur corridor, which connects

Azerbaijan to the city of Nakhchivan, but Armenia

slowed the project down by demanding that roads and communications networks be

built following Armenian law.) This is to say nothing of the recently increased

transportation costs and problems obtaining insurance and fuel.

Nagorno Karabakh and Zangezur

Corridor

For these reasons,

Turkey and Russia are neither allies nor strategic partners, for geopolitical

tension will always be embedded in their relationship. But economic realities

and the need for domestic stability periodically trump whatever rivalries they

have, leading to spasms of cooperation based on specific projects. Turkey plays

an essential role as Russia becomes more geographically and economically

isolated. Because their relationship indirectly benefits the West, the West is

fine with letting them come to terms. As long as there is interest in these

relations, Turkey and Russia will see further growth in cooperation.

For updates click hompage here