By Eric Vandenbroeck

Turkey In Context

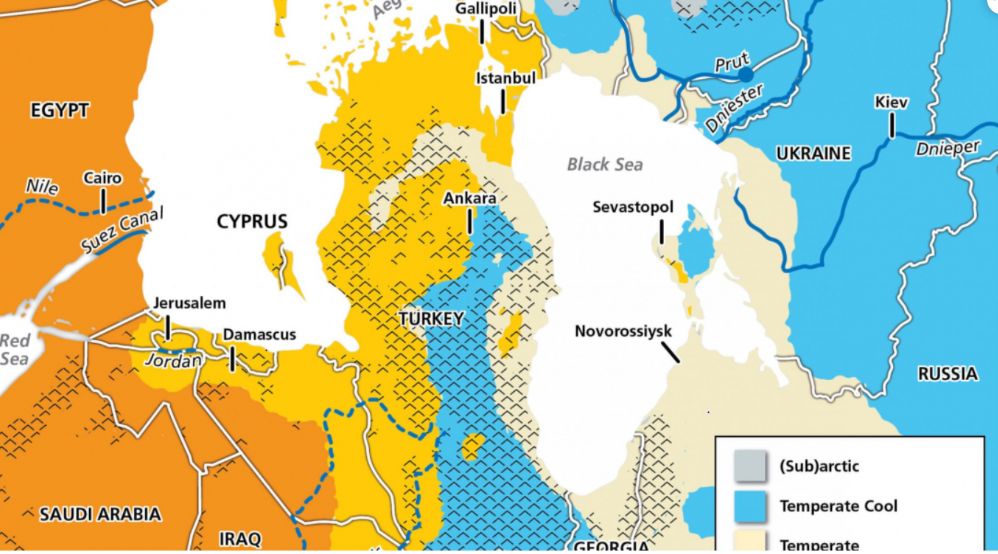

The Sea of Marmara

(/ˈmɑːrmərə/; Turkish: Marmara Denizi;

Greek: Θάλασσα του Μαρμαρά, Ancient Greek: Προποντίς, Προποντίδα), also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara

Sea, and in the context of classical antiquity as the Propontis, is the inland

sea, entirely within the borders of Turkey, that connects the Black Sea to the

Aegean Sea, thus separating Turkey's Asian and European parts. The Sea of

Marmara, a northeastern extension of the Mediterranean Sea, separates Asian

Turkey from European Turkey (Trace), thus it separates the two continents.

It contains two

island groups; the Marmara in the southwest and the

Princes' in the northeast. On the small island of Imrali

stands a maximum-security prison that holds just a few prisoners, including

Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of PKK, considered a Kurdish terrorist group.

A condition of the post–World War I settlement forced

Marmara and the Turkish Straits open to international traffic. Not only had

land-based global trade between Asia and Europe evaporated because of the

better logistics of deep water transport but now the

Turks couldn’t even charge duties on the regional trade passing through the

Bosporus and Dardanelles, even though all that trade sailed through downtown

Istanbul.

The Soviet rise in

the 1920s and domination of Central Europe at the end of the Second World War

next not only completely locked the Turks out of what once had been some of

their richest territories, but also out of what once had been lucrative markets

of the Black Sea littoral. The Danube, Dniester, Dnieper, Don, and Volga

systems were now all internal waterways of the newly risen Soviet Empire, and

Soviet ideology frowned on trading with outsiders.

Next, the creation of Israel and the subsequent Arab-Israeli standoff ended nearly all trade within, much

less through, the final economically interesting bit of the former Ottoman

Empire: the Levant.

But the most damning

was the Americans’ new Order. In dismantling the empires and making the oceans

safe for everyone, the Americans extinguished any hope of the Turks’ geography

mattering at all to global trade. The Americans forced all the world’s waterways

to be part of the global commons.

If goods can go from

any port to any other port without needing to be concerned about either safety

on the high seas or persnickety local naval powers, then the specific location.

Traders certainly didn’t need a central land-based clearinghouse. What had made

the Turks special, critical, evaporated. Marmara was still nice, and it ensured

the Turks remained the most powerful people in their (suddenly much smaller)

neighborhood, but no longer was it a kernel of an empire.

Today, many,

particularly Europeans, see the Turkish economy is substandard compared with

Northern European norms, with a far heavier emphasis on lower-skilled

industries like textiles and basic manufacturing.

However Turkey(while) may have

(strong) European tendencies and influences, but it isn’t part of the Northern

European Plain. Any comparisons must evaluate Turkey within its neighborhood:

the Black Sea Basin, the Eastern Balkans, the Western Mediterranean, and the

Middle East. In that neighborhood Turkey, isolated, insular, insular, is

already the regional power.

Turkey’s physical

location makes it the obvious connection point for such land-based transport

between Europe and the Middle East, and with roads and rail lines snaking in

all directions, with the Cold War’s end and the reopening of the former Soviet

space, trade from Europe, the Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Hordelands is once again flowing to Turkish ports, into

Marmara and beyond to the Mediterranean. Even in the unfortunate circumstance

that Turkey ends up crossing swords with the Russians, there will be far more

trade on the Black and through Marmara than there ever was under the Order.

Without American-enforced freedom of the seas, the Turks can return the

Bosporus and Dardanelles to their normal status of being internal waterways.

Everyone will have to pay the Turks to sail through.

Turkey the Middle East and the Balkans

The Middle East is

replete with examples of two local powers rising simultaneously, clashing, and

containing each other’s ambitions and opportunities to the point that they

massively weaken each other. Then a third power comes in and sweeps the board.

Saudi Arabia and Iran both fancy themselves regional powers. As the Turks have

far more military and economic capacity than the pair combined, the Turks find

the Saudi-Iranian battle for influence rather

adorable.

The Turks however

also reserve the option of interfering in the Saudi-Iranian

fight and settling it however they choose. The real fireworks of the Iranian-Saudi confrontation potentially could happen in

densely populated Mesopotamia, corresponding to today's Iraq, mostly, but also

parts of modern-day Iran, Syria, and Turkey.

The Soviet rise

barred commerce and contact with former imperial possessions to the northwest,

north, and northeast. The hostile, arid geography of the Middle East combined

with the rise of mutually hostile and/or totalitarian governments that cared

little about economic development or trade walled off the south. The only

“open” border the Turks had was with Iran, the

adjoining territories being physically rugged and far removed from the two

countries’ capital regions, both in terms of distance and culture.

For the Turks, the

brightest spot in this emerging world is the Eastern Balkans. The reasons are

legion.

The Americans

destroyed most of the Danubian bridges in Serbia

during the Kosovo War. The Eastern Balkan pair is not as integrated into Europe

now, a decade after EU and NATO membership, as closer countries, like Poland,

Latvia, and Hungary, were before EU and NATO membership.

Bulgaria and

Romania’s relative poverty compared with the rest of Europe enables the

Bulgarians and Romanians to switch partners with relative ease.*

Because the Turkish Straits are the best maritime connection between them and

the wider world, there’s not much wiggle room in choosing a post-Order. Both

Bulgaria and Romania are significant agricultural exporters, and between the

two and Turkey, nearly every climate zone that generates foodstuffs is

represented.

Above all else, the

Bulgarians and Romanians will be willing. Both Sofia and Bucharest realize that

their chances for charting their own destiny, even if the two allied, are zero.

The Balkan and Carpathian Mountains box them in, the Russians dominate their

northeast, the Turks their southeast, the Germans they're northwest, and any

access to the wider world requires the purposeful and ongoing permission of

multiple other powers. They are quintessential examples of the sort of

countries that have no long-term hope of survival

outside of the global management structures of the Order.

That is, they have no

chance without a sponsor. On their own, they are prey but partner them with the

Turks, and their position shifts from pathetic to enviable. They gain entrée to

a country with energy security, a market twice the size of their own combined,

and access to the Mediterranean Basin, something otherwise impossible. Defense

guarantees from Turkey may not have the gold-star value of those from the

United States, but the Turkish military is both competent and close by. Best be

on its good side.

While I mentioned Japans potential problem is

China Turkey's potential problem is (and has historically been) Russia.

Russia’s competition with

Europe will end meaningful oil and natural gas exports via the Baltic Sea and

North European Plain. The only other large-scale route is southwest via the

Black Sea and Turkish Straits. Even a minor military conflict with Turkey would

utterly end Russia’s ability to export oil and natural gas to the west,

removing it from the list of significant energy exporters (it currently ranks

number one for combined oil, natural gas, and petroleum products, with oil and

natural gas sales being the government’s top two sources of income).

The optimal time for

Turkish potential action would be once the Russians become fully committed

against the Northern Europeans. At that point the Russians would have fewer

forces to spare to a front in the south, vastly improving the success rate of

what would have to be a sizable amphibious assault.

The optimal place

would be the Crimean Peninsula, Turkish control of which would eliminate the

only meaningful Russian naval presence on the Black Sea, turning it into a

Turkish lake. Because the Crimea’s link to mainland Ukraine is only three miles

wide, defending it from a mainland assault would be easy. While Turkey’s air

force couldn’t hold its own against Russia in a one-on-one fight, Russian

forces would already be engaged against every country that borders the Baltic

Sea. It wouldn’t take much Turkish strike capacity to sever most of the Russian

army’s supply lines into western Ukraine and even Belarus. And the Turks would

have local help: the Crimea’s Ukrainian and Tatar minorities would likely view

the Turks as liberators from Russian occupation.

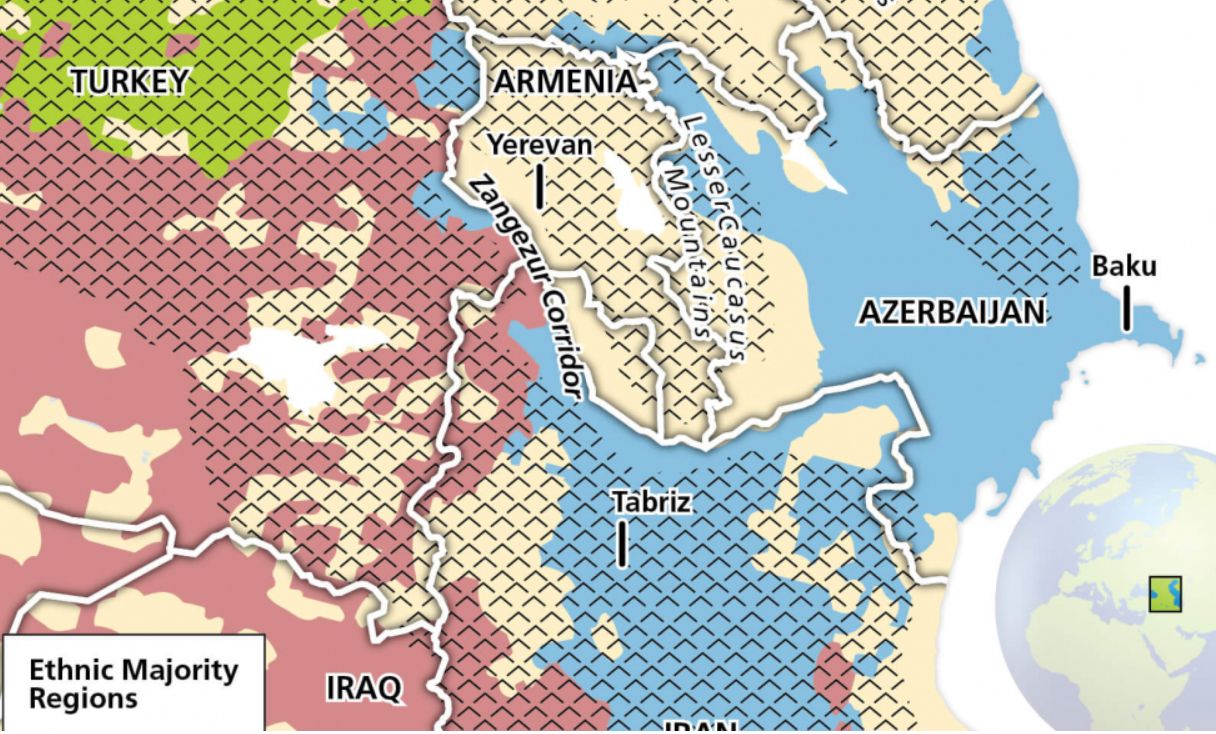

Russia already has

thousands of airmen and soldiers in not just the Crimea, but also Armenia and

in secessionist regions in Georgia. Turkish intrusion into the Crimea or

Azerbaijan would so change the facts on the ground that the Russians would feel

they have no choice but to use every tool at their disposal, from prompting a

Kurdish insurrection in eastern Turkey to a sponsoring an Armenian assault into

Georgia to bombing Istanbul itself. High reward brings high risk.

The Syrian problem

Pre-Order interior

“Syria” was a caravan route throughout lightly populated terrain, dotted with a

quartet of ancient oasis cities, Aleppo, Homs, Hama, and Damascus. But the

Order’s freeing of the global ocean combined with its shattering of the empires

ended the caravan trade while erecting hard political borders. The people of

Syria could no longer trade for food; they had to find something else.

The Syrian Civil War,

first and foremost, is a civilizational collapse with its roots in national

starvation. Which is damnably inconvenient for a newly emergent Turkey. Even if

the Syrian Civil War ended today, there isn’t enough water and oil to feed the

population. Syria will not, will never, recover.

Rivers of Syrian

refugees into Turkey are the new normal, for they’ve nowhere else to flow. The

Saudi and Iraqi borders are hard desert. That leaves Turkey.

Iran and the Azeris

Because the Azeris are Iran’s largest minority group, extra effort

has gone into grinding as much of the Turk out of the Azerbaijanis as possible.

While most Iranian Azeris certainly still consider themselves of Turkic

descent, that is not the same as saying they consider themselves anti-Persian

or fully Turkish. For example, the dominant religion among Iranian Azeris is

Shia Islam, the same as the Persians, and not the Sunni Islam practiced in

Turkey. The Turks will certainly enjoy the support of a large fifth column in

any invasion, but they will not be categorically welcomed.

Iran has tools beyond

its military. Iranian intelligence assets at any given

time are active in Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria,

Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories, . . . and Turkey. In times of Turkish-Iranian hostility, Iran has worked overtime to stoke

tensions and militancy among Turkey’s many mountain minorities and political

factions, most notably the Kurdish population. And because any Turkish assault

on Iran would need to pass through Turkey’s own Kurdish region, Iran would

undoubtedly work to set that entire region on fire. Even if Turkey could seize

northwestern Iran, holding on to it would be a whole other problem.

This whole scenario

seems like more trouble than it’s worth, but it is worth considering, for two

reasons.

First, most of

Turkey’s border regions have interlocking issues. Going into Romania can lead

to confrontation with Russia, which can lead to intervention in Ukraine, which

naturally leads to competition in Azerbaijan, which means Turkish forces in Zangezur, which means Tabriz is in play. Whoever has

controlled Marmara, their top problem has always been the spiraling combination

of seemingly unrelated topics and theaters into a royal, untangleable

mess.

Economically, the

Balkan advance makes the most sense. Ethnically, it is difficult to argue

against grabbing the Azerbaijans. Going southeast

solves both an internal security issue as well as an energy dependency. Taking Cyprus would be a strategic coup and give the

Turks leverage against all of Europe. Grabbing Crimea would condemn the Turks’

most powerful historical foe to dissolution. What is clear is that Turkey has

options, and that includes options for the fights it will pick.

Options make the

foreign policy of contemporary Turkey seem erratic. Within the past decade, the

Turks have offered Armenia peace and threatened it with invasion, funded some

infrastructure in (independent) Azerbaijan while also haranguing Baku on other projects,

cozied up to Russia economically but shot down a Russian jet, alternately let

Syrian migrants flow through its territories to Europe and stopped them,

encouraged Islamic militants to flow into Syria and then invaded Syria to kill

them, encouraged Iraqi Kurds to ship their oil through Turkish territory while

invading Iraqi Kurdistan, and competed with the Iranians for influence in

Azerbaijan and Iraq while also helping the Iranians with US sanctions.

This said the

Europeans and Russians wouldn’t like the Turks moving into the Eastern Balkans.

The Russians and Iranians wouldn’t like the Turks moving into the Caucasus. The

Iranians obviously wouldn’t be keen on the Turks moving into Iranian

Azerbaijan, while neither the Iranians nor the Saudis would like to see Turkish

troops moving into Iraq at all. Turkish forces there would be able to cut off

any Iranian assault on Saudi Arabia in a day, while the last thing the Saudis

want to see on their northern border is a functional state and military.

If Turkey is forced

to deploy a hundred thousand troops or so to stabilize Syria, it will largely

occupy Turkish strategic attention for years, absorbing any military bandwidth

that might have been used to venture in to Greece or

Romania or Crimea or Azerbaijan or Iran. It would also enable Russia, Iran, and

Saudi Arabia to pin Turkey down more firmly by spawning violence in the

occupied areas.

Turkey will always be

smack dab in the middle of everything. It’s relationships with outside powers may wax and wane, but

it will always be the economic and military heavyweight of its region.

For updates click homepage here