By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

US New World War?

The United States is

a heartbeat away from a world war that it could lose. There are serious conflicts

requiring U.S. attention in two of the world’s three most strategically

important regions. Should China decide to launch an attack on Taiwan, the

situation could quickly escalate into a global war on three fronts, directly or

indirectly involving the United States. The hour is late, and while there are

options for improving the U.S. position, they all require serious effort and

inevitable trade-offs. It’s time to move with real urgency to mobilize the

United States, its defenses, and its allies for what could become the world

crisis of our time.

Describing the United

States’ predicament in such stark terms may strike many readers as alarmist.

The United States has long been the most powerful nation on earth. It won two

world wars, defeated the Soviet Union, and still possesses the world’s top military.

For the past year and a half, the United States has been imposing gigantic

costs on Russia by supporting Ukraine—so much so that it seemed

conceivable to

this author that the United States might be able to sequence its contests by

inflicting a decisive defeat by proxy on Russia before turning its primary

attention to strengthening the U.S. military posture in the Indo-Pacific.

But that strategy is

becoming less viable by the day. As Russia mobilizes for a long war in Ukraine and a new front opens in the Levant,

the temptation will grow for a rapidly arming China to make a move on Taiwan.

Already, Beijing is testing

Washington in East Asia,

knowing full well that the United States would struggle to deal with a third geopolitical

crisis. If war does come, the United States would find some very important

factors suddenly working against it.

One of those factors

is geography. As the last two U.S. National Defense Strategies made clear and

the latest Congressional Strategic Posture Commission confirmed, today’s U.S. military is not designed to fight wars

against two major rivals simultaneously. In the event of a Chinese attack on

Taiwan, the United States would be hard-pressed to rebuff the attack while keeping up the flow

of support to Ukraine and Israel.

This isn’t because

the United States is in decline. It’s because unlike the United States, which

needs to be strong in all three of these places, each of its adversaries—China,

Russia, and Iran—only has to be strong in its own home region to achieve its objectives.

The worst-case

scenario is an escalating war in at least three far-flung

theaters, fought by a thinly

stretched U.S. military alongside ill-equipped allies that are mostly unable

to defend

themselves against

large industrial powers with the resolve, resources, and ruthlessness to

sustain a long conflict. Waging this fight would require a scale of national

unity, resource mobilization, and willingness to sacrifice that Americans and

their allies have not seen in generations.

The United States has

fought multiple wars before. But in past conflicts, it was always able to

outproduce its opponents. That’s no longer the case: China’s navy is already

bigger than the United States in terms of sheer number of ships, and it’s growing by the equivalent of the entire French Navy (about

130 vessels, according to the French naval chief of staff) every four years. By

comparison, the U.S. Navy plans an expansion by 75 ships over the next decade.

A related

disadvantage is money. In past conflicts, Washington could easily outspend

adversaries. During World War II, the U.S. national debt-to-GDP ratio almost

doubled, from 61 percent of GDP to 113 percent. By contrast, the United States

would enter a conflict today with debt already in excess of 100 percent of GDP.

All of that pales

alongside the human costs that the United States could suffer in a global

conflict. Large numbers of U.S. service members would likely die. Some of the

United States adversaries have conventional and nuclear capabilities that can

reach the U.S. homeland; others have the ability to inspire or direct

Hamas-style terrorist attacks on U.S. soil, which may be easier to carry out

given the porous state of the U.S. southern

border.

“My gut tells me we

will fight in 2025,” U.S. Air Force Gen. Mike Minihan wrote in a January

memo to officers in the Air Mobility Command. The memo, which promptly leaked to reporters, warned that the United States and

China were barreling toward a conflict over Taiwan. The U.S. Defense Department

quickly distanced itself from Minihan’s blunt assessment. Yet the general

wasn’t saying anything in private that military and civilian officials weren’t

already saying in public.

In August 2022, a

visit to Taiwan by U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi set off the worst cross-strait crisis in a quarter century.

China’s aircraft barreled across the center line of the Taiwan Strait; its

ships prowled the waters around the island; its ballistic missiles splashed

down in vital shipping lanes. Months after Russia’s full-scale invasion of

Ukraine had reminded everyone that major war is not an anachronism, the Taiwan

crisis made visceral the prospect that a Chinese attack on that island could

trigger conflict between the world’s two top powers.

Washington certainly took

note. A year earlier, the outgoing chief of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Adm.

Philip Davidson, had predicted that a war in the Taiwan Strait could come by

2027. After the August crisis, this “Davidson window” became something like conventional

wisdom, with Minihan, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and other U.S. officials predicting that trouble might start even sooner. If the

United States and China do clash over Taiwan, it will be the war everyone saw

coming—which would make the failure to deter it all the more painful.

To be sure, U.S.

President Joe Biden has made deterring that conflict a priority. Despite the

long-standing policy of “strategic ambiguity,” Biden has publicly affirmed,

four times, that the United States would come to Taiwan’s aid if it were

attacked. Yet deterrence is about more than declaratory policy: It requires

assembling a larger structure of constraints that preserve the peace by

instilling fear of the outcome and consequences of war. More than a year after

the August crisis and nearly three years into the Davidson window, the United

States and its friends are struggling to build that structure in the limited

time they may have left.

Taiwan is important

in many ways—as a critical node in technology supply chains, as a

democracy menaced by an aggressive autocracy, and as an unresolved legacy of

China’s civil war. Yet Taiwan has become the world’s most perilous flash point

mostly for strategic reasons.

Taiwan is a “lock

around the neck of a great dragon,” as Chinese military analyst Zhu Tingchang has written. It anchors the first island chain, the string of

U.S. allies and partners that block China from the open Pacific. If China were

to take Taiwan, it would rupture this defense perimeter, opening the way to

greater influence—and coercion—throughout the region and beyond.

In 1972, Chinese

leader Mao Zedong told U.S. President Richard Nixon that Beijing could

wait 100 years to reclaim Taiwan. China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, is not so

patient. He has said the island’s awkward status cannot be passed from

generation to generation; he has reportedly ordered the People’s Liberation Army to be ready

for action by 2027. Militaries constantly prepare for missions they never

execute, of course. But the risk of war is rising as China’s capabilities—and

urgency—grow.

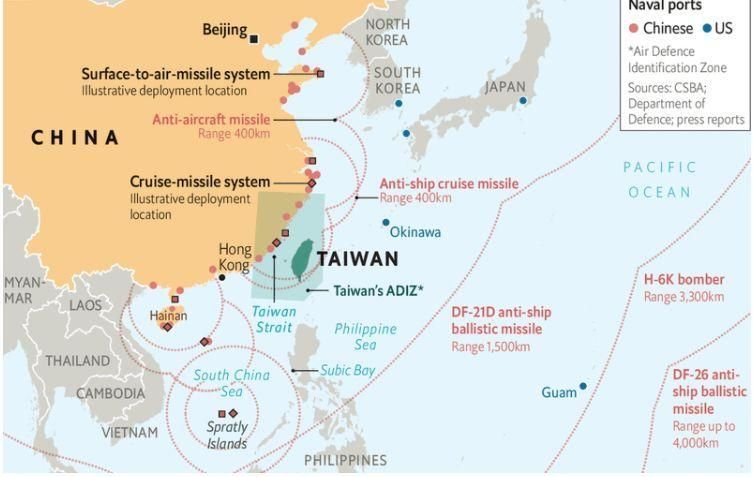

Beijing is reaping

the rewards of a multidecade buildup focused on the ships, planes, and other

platforms needed to project power into the Western Pacific; the

“counter-intervention” capabilities, such as anti-ship missiles and

sophisticated air defenses, needed to keep U.S. forces at bay; and now the

nuclear capabilities needed to enhance China’s options for deterrence and

coercion alike. The scale and scope of these programs are remarkable. Adm. John

Aquilino, Davidson’s successor at Indo-PacificCommand, said in April that China

has embarked on “the largest, fastest, most comprehensive military buildup

since World War II.” As a result, the balance is changing fast. By the late

2020s, several recent assessments

indicate, Washington might find it extremely hard to save Taiwan from a determined assault.

Xi would surely

prefer to take Taiwan without a fight. He currently aims to coerce unification

through military, economic, and psychological pressure short of war. Yet this

strategy isn’t working. Having witnessed Xi’s brutal crackdown in Hong Kong,

the Taiwanese populace has little interest in unification. Since 2016, the more

hawkish, pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has thumped the

more Beijing-friendly Kuomintang in presidential elections. If the DPP wins the

next presidential race in January 2024—its candidate, Lai Ching-te, currently

leads the polls—Xi might conclude that coercion has failed and consider more

violent options.

Biden knows the

threat is rising—he recently called China a “ticking time bomb”—which is why he has

repeatedly said Washington won’t stand aside if Beijing strikes. But make no

mistake: A great-power war over Taiwan would be cataclysmic. It would feature

combat more vicious than anything the United States has experienced in

generations. It would fragment the global economy and pose real risks of

nuclear escalation. So the crucial question is whether Washington can deter a

conflict it hopes never to fight.

China’s fundamental

advantages are proximity and the mass of forces it can muster in a war off its

coast. The U.S. advantage is that control is harder than denial, especially

when control requires crossing large contested bodies of water. An invasion of Taiwan,

with its oceanic moat and rugged terrain, would be one of history’s most daunting military operations, comparable to the Allied

invasion of Normandy in 1944. Options short of invasion, such as blockade or

bombardment, offer no guarantee of forcing Taiwan to submit. Given the risk

that a failed war could pose to Xi’s regime and perhaps his life, the Chinese

leader will probably want a high chance of success if he attacks. So the United

States and other countries should be able to inject enough doubt into this

calculus that even a more risk-acceptant Xi decides rolling the iron dice is a bad

idea.

This will require two

mutually reinforcing types of deterrence. “Deterrence by denial” convinces an

enemy not to attack by persuading him that the effort will fail. The ability to

deter invasion, in this sense, is synonymous with the ability to defeat it.

“Deterrence by punishment” convinces an enemy not to attack by persuading him

that the effort—even if successful—will incur an exorbitant price. The

strongest deterrents blend denial and punishment. They confront an aggressor

with sky-high costs and a low likelihood of success. The U.S. task in the

Western Pacific, then, is to show that Taiwan can survive a Chinese attack—and

that any such war will leave China far poorer, weaker, and less politically

stable than before.

In practice, this

approach would rest on five pillars: first, a Taiwan that can deny China a

quick or easy victory because it is bristling with arms and ready to resist to

the end; second, a U.S. military that can sink a Chinese invasion fleet,

decimate a blockading squadron, and otherwise turn back hostile forces trying

to take Taiwan; third, a coalition of allies that can bolster this denial

defense while raising the strategic price China pays by forcing it to fight a

sprawling, regionwide war; fourth, a global punishment campaign that batters

China’s economy—and perhaps its political system—regardless of whether Beijing

wins or loses in the Taiwan Strait; and fifth, a credible ability to fight a

nuclear war in the Western Pacific—if only to convince China that it cannot use

its own growing arsenal to deter the United States from defending Taiwan.

If these steps sound

awful to contemplate, they are. Deterrence involves preparing for the

unthinkable to lessen the likelihood it occurs. The United States and its

friends are making real, even historic progress in all these areas. Alas, they

are still struggling to get ahead of the threat.

For updates click hompage here