By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Way Forward In Ukraine

In the early hours of

February 24, 2022, the Russian air force struck targets across Ukraine. At the same

time, Moscow’s infantry and armor poured into the country from the north, east,

and south. In the days that followed, the Russians attempted to encircle Kyiv.

These were the first

days and weeks of an invasion that could well have resulted in Ukraine’s defeat

and subjugation by Russia. In retrospect, it seems almost miraculous that it

did not.

What happened on the

battlefield is relatively well understood. What is less understood is the

simultaneous intensive diplomacy involving Moscow, Kyiv, and a host of other

actors, which could have resulted in a settlement just weeks after the war

began.

By the end of March

2022, a series of in-person meetings in Belarus and Turkey and virtual

engagements over video conference had produced the so-called Istanbul

Communiqué, which described a framework for a settlement. Ukrainian and Russian

negotiators then began working on the text of a treaty, making substantial

progress toward an agreement. But in May, the talks broke off. The war raged on

and has since cost tens of thousands of lives on both sides.

What Happened? How Close Were The Parties To Ending

The War? And Why Did They Never Finalize A Deal?

To shed light on this

often overlooked but critical episode in the war, we have examined draft

agreements exchanged between the two sides, some details of which have not been

reported previously. We have also conducted interviews with several participants

in the talks as well as with officials serving at the time in key Western

governments, to whom we have granted anonymity in order to discuss sensitive

matters. And we have reviewed numerous contemporaneous and more recent

interviews with and statements by Ukrainian and Russian officials who were

serving at the time of the talks. Most of these are available on YouTube but

are not in English and thus not widely known in the West. Finally, we

scrutinized the timeline of events from the start of the invasion through the

end of May, when talks broke down. When we put all these pieces together, what

we found is surprising—and could have significant implications for future

diplomatic efforts to end the war.

Some observers and

officials (including, most prominently, Russian President Vladimir Putin) have

claimed that there was a deal on the table that would have ended the war but

that the Ukrainians walked away from it due to a combination of pressure from their

Western patrons and Kyiv’s own hubristic assumptions about Russian military

weakness. Others have dismissed the significance of the talks entirely,

claiming that the parties were merely going through the motions and buying time

for battlefield realignments or that the draft agreements were unserious.

Although those

interpretations contain kernels of truth, they obscure more than they

illuminate. There was no single smoking gun; this story defies simple

explanations. Further, such monocausal accounts elide completely a fact that,

in retrospect, seems extraordinary: amid Moscow's unprecedented aggression, the

Russians and the Ukrainians almost finalized an agreement that would have ended

the war and provided Ukraine with multilateral security

guarantees, paving the way to its permanent neutrality and, down the road,

its membership in the EU.

A final agreement

proved elusive, however, for several reasons. Kyiv’s Western partners were

reluctant to be drawn into a negotiation with Russia, particularly one that

would have created new commitments for them to ensure Ukraine’s security. The

public mood in Ukraine hardened with the discovery of Russian atrocities at Irpin and Bucha.

And, with the failure of Russia’s encirclement of Kyiv, President Volodymyr

Zelensky became more confident that, with sufficient Western support, he could

win the war on the battlefield. Finally, although the parties’ attempt to

resolve long-standing disputes over the security architecture offered the

prospect of a lasting resolution to the war and enduring regional stability,

they aimed too high, too soon. They tried to deliver an overarching settlement

even as a basic ceasefire proved out of reach.

Today, when the

prospects for negotiations appear dim and relations between the parties are

nearly nonexistent, the history of the spring 2022 talks might seem like a

distraction with little insight directly applicable to present circumstances.

But Putin and Zelensky surprised everyone with their mutual willingness to

consider far-reaching concessions to end the war. They might well surprise

everyone again in the future.

Assurance Or Guarantee?

What did the Russians

want to accomplish by invading Ukraine? On February 24, 2022, Putin gave a

speech in which he justified the invasion by mentioning the vague goal of “denazification” of the country. The most reasonable

interpretation of “denazification” was that

Putin sought to topple the government in Kyiv, possibly killing or capturing

Zelensky in the process.

Yet days after the

invasion began, Moscow began probing to find grounds for a compromise. A war

Putin expected to be a cakewalk was already proving anything but, and this

early openness to talking suggests he appears to have already abandoned the

idea of outright regime change. Zelensky, as he had before the war, voiced an

immediate interest in a personal meeting with Putin. Though he refused to talk

directly with Zelensky, Putin did appoint a negotiating team. Belarussian

President Alexander Lukashenko played the part of mediator.

The talks began on

February 28 at one of Lukashenko’s spacious countryside residences near the

village of Liaskavichy, about 30 miles from the

Ukraine-Belarus border. The Ukrainian delegation was headed by Davyd Arakhamia,

the parliamentary leader of Zelensky’s political party, and included Defense

Minister Oleksii Reznikov, presidential adviser Mykhailo Podolyak, and other

senior officials. The Russian delegation was led by Vladimir

Medinsky, a senior adviser to the Russian president who had earlier served

as culture minister. It also included deputy ministers of defense and foreign

affairs, among others.

At the first meeting,

the Russians presented a set of harsh conditions, effectively demanding

Ukraine’s capitulation. This was a nonstarter. But as Moscow’s position on the

battlefield continued to deteriorate, its positions at the negotiating table

became less demanding. So on March 3 and March 7, the parties held a second and

third round of talks, this time in Kamyanyuki,

Belarus, just across the border from Poland. The Ukrainian delegation presented

demands of their own: an immediate cease-fire and the establishment of

humanitarian corridors that would allow civilians to safely leave the war zone. It

was during the third round of talks that the Russians and the Ukrainians appear

to have examined drafts for the first time. According to Medinsky, these were Russian drafts, which Medinsky’s delegation brought from Moscow and

which probably reflected Moscow’s insistence on Ukraine’s neutral status.

At this point,

in-person meetings broke up for nearly three weeks, though the delegations continued

to meet via Zoom. In those exchanges, the Ukrainians began to focus on the

issue that would become central to their vision of the endgame for the war:

security guarantees that would oblige other states to come to Ukraine’s defense

if Russia attacked again in the future. It is not entirely clear when Kyiv

first raised this issue in conversations with the Russians or Western

countries. But on March 10, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba, then in

Antalya, Turkey, for a meeting with his Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov,

spoke of a “systematic, sustainable solution” for Ukraine, adding that the

Ukrainians were “ready to discuss” guarantees it hoped to receive from NATO

member states and Russia.

Podolyak and Ukrainian Ambassador to Turkey Vasyl

Bodnar after a meeting with the Russians, Istanbul, March 2022

What Kuleba seemed to

have in mind was a multilateral security guarantee, an arrangement whereby

competing powers commit to the security of a third state, usually on the

condition that it will remain unaligned with any of the guarantors. Such

agreements had mostly fallen out of favor after the Cold War. Whereas alliances

such as NATO intend to maintain collective defense

against a common enemy, multilateral security guarantees are designed to

prevent conflict among the guarantors over the alignment of the guaranteed

state, and by extension to ensure that state’s security.

Ukraine had a bitter

experience with a less ironclad version of this sort of agreement: a

multilateral security assurance, as opposed to a guarantee. In 1994, it signed

on to the so-called Budapest Memorandum, joining the Nuclear Nonproliferation

Treaty as a nonnuclear weapons state and agreeing to give up what was then the

world’s third-largest arsenal. In return, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the

United States promised that they would not attack Ukraine. Yet contrary to a

widespread misconception, in the event of aggression against Ukraine, the

agreement required the signatories only to call a UN Security Council meeting,

not to come to the country’s defense.

Russia’s full-scale

invasion—and the cold reality that Ukraine was fighting an existential war on

its own—drove Kyiv to find a way to both end the aggression and ensure it never

happened again. On March 14, just as the two delegations were meeting via Zoom,

Zelensky posted a message on his Telegram channel calling for “normal, effective security guarantees” that

would not be “like the Budapest ones.” In an interview with Ukrainian

journalists two days later, his adviser Podolyak explained that what Kyiv sought were “absolute security

guarantees” that would require that “the signatories . . . do not stand aside

in the event of an attack on Ukraine, as is the case now. Instead, they [would]

take an active part in defending Ukraine in a conflict.”

Ukraine’s demand not

to be left to fend for itself again is completely understandable. Kyiv wanted

(and still wants) to have a more reliable mechanism than Russia’s goodwill for

its future security. But getting a guarantee would be difficult. Naftali Bennett

was the Israeli prime minister at the time the talks were happening and was

actively mediating between the two sides. In an interview with journalist

Hanoch Daum posted online in February 2023, he recalled that he

attempted to dissuade Zelensky from getting stuck on the question of security

guarantees. “There is this joke about a guy trying to sell the Brooklyn Bridge

to a passerby,” Bennett explained. “I said: ‘America will give you guarantees?

It will commit that in several years if Russia violates something, it will send

soldiers? After leaving Afghanistan and all that?’ I said: ‘Volodymyr, it won’t

happen.’”

To put a finer point

on it: if the United States and its allies were unwilling to provide Ukraine

such guarantees (for example, in the form of NATO membership) before the war,

why would they do so after Russia had so vividly demonstrated its willingness to

attack Ukraine? The Ukrainian negotiators developed an answer to this question,

but in the end, it didn’t persuade their risk-averse Western colleagues. Kyiv’s

position was that, as the emerging guarantees concept implied, Russia would be

a guarantor, too, which would mean Moscow essentially agreed that the other

guarantors would be obliged to intervene if it attacked again. In other words,

if Moscow accepted that any future aggression against Ukraine would mean a war

between Russia and the United States, it would be no more inclined to attack

Ukraine again than it would be to attack a NATO ally.

A Breakthrough

Throughout March,

heavy fighting continued on all fronts. The Russians attempted to take

Chernihiv, Kharkiv, and Sumy but failed spectacularly, though all three cities

sustained heavy damage. By mid-March, the Russian army’s thrust toward Kyiv had

stalled, and it was taking heavy casualties. The two delegations kept up talks

over videoconference but returned to meeting in person on March 29, this time

in Istanbul, Turkey.

There, they appeared

to have achieved a breakthrough. After the meeting, the sides announced they

had agreed to a joint communiqué. The terms were broadly described during the

two sides’ press statements in Istanbul. But we have obtained a copy of the full

text of the draft communiqué, titled “Key Provisions of the Treaty on Ukraine’s

Security Guarantees.” According to participants we interviewed, the Ukrainians

had largely drafted the communiqué and the Russians provisionally accepted the

idea of using it as the framework for a treaty.

The treaty envisioned

in the communiqué would proclaim Ukraine as a permanently neutral, nonnuclear

state. Ukraine would renounce any intention to join military alliances or allow

foreign military bases or troops on its soil. The communiqué listed as possible

guarantors the permanent members of the UN Security Council (including Russia)

along with Canada, Germany, Israel, Italy, Poland, and Turkey.

The communiqué also

said that if Ukraine came under attack and requested assistance, all guarantor

states would be obliged, following consultations with Ukraine and among

themselves, to provide assistance to Ukraine to restore its security.

Remarkably, these obligations were spelled out with much greater precision than

NATO’s Article 5: imposing a no-fly zone, supplying

weapons, or directly intervening with the guarantor state’s military force.

Although Ukraine

would be permanently neutral under the proposed framework, Kyiv’s path to EU

membership would be left open, and the guarantor states (including Russia)

would explicitly “confirm their intention to facilitate Ukraine’s membership in

the European Union.” This was nothing short of extraordinary: in 2013, Putin

had put intense pressure on Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych to back out

of a mere association agreement with the EU. Now, Russia was agreeing to

“facilitate” Ukraine’s full accession to the EU.

Although Ukraine’s

interest in obtaining these security guarantees is clear, it is not obvious why

Russia would agree to any of this. Just weeks earlier, Putin had attempted to

seize Ukraine’s capital, oust its government, and impose a puppet regime. It seems

far-fetched that he suddenly decided to accept that Ukraine—which was now more

hostile to Russia than ever, thanks to Putin’s actions—would become a member of

the EU and have its independence and security guaranteed by the United States

(among others). And yet the communiqué suggests that was precisely what Putin

was willing to accept.

We can only

conjecture as to why. Putin’s blitzkrieg had failed; that was clear by early

March. Perhaps he was now willing to cut his losses if he got his

longest-standing demand: that Ukraine renounce its NATO aspirations and never

host NATO forces on its territory. If he could not control the entire country,

at least he could ensure his most basic security interests, stem the

hemorrhaging of Russia’s economy, and restore the country’s international

reputation.

The communiqué also

includes another provision that is stunning, in retrospect: it calls for the

two sides to seek to peacefully resolve their dispute over Crimea during the

next ten to 15 years. Since Russia annexed the peninsula in 2014, Moscow has

never agreed to discuss its status, claiming that it was a region of Russia no

different than any other. By offering to negotiate over its status, the Kremlin

had tacitly admitted that was not the case.

Fighting And Talking

In remarks he made on

March 29, immediately after the conclusion of the talks, Medinsky, the head of

the Russian delegation, sounded decidedly upbeat, explaining that the

discussions of the treaty on Ukraine’s neutrality were entering the practical

phase and that—allowing for all the complexities presented by the treaty having

many potential guarantors—it was possible that Putin and Zelensky would sign it

at a summit in the foreseeable future.

The next day, he told

reporters that “yesterday, the Ukrainian side, for the first time fixed in a

written form its readiness to carry out a series of most important conditions

for the building of future normal and good-neighborly relations with Russia.”

He continued: “They handed to us the principles of a potential future

settlement, fixed in writing.”

Meanwhile, Russia had

abandoned its efforts to take Kyiv and was pulling back its forces from the

entire northern front. Alexander Fomin, Russia’s deputy minister of defense,

had announced the decision in Istanbul on March 29, calling it an effort “to build

mutual trust.” In fact, the withdrawal was a forced retreat. The Russians had

overestimated their capabilities and underestimated the Ukrainian resistance

and were now spinning their failure as a gracious diplomatic measure to

facilitate peace talks.

The withdrawal had

far-reaching consequences. It stiffened Zelensky’s resolve, removing an

immediate threat to his government, and demonstrated that Putin’s vaunted

military machine could be pushed back, if not defeated, on the battlefield. It

also enabled large-scale Western military assistance to Ukraine by freeing up

the lines of communication leading to Kyiv. Finally, the retreat set the stage

for the gruesome discovery of atrocities that Russian forces had committed in

the Kyiv suburbs of Bucha and Irpin, where they had raped, mutilated, and

murdered civilians.

Reports from Bucha

began to make headlines in early April. On April 4, Zelensky visited the town.

The next day, he spoke to the UN Security Council via video and accused Russia

of perpetrating war crimes in Bucha, comparing Russian forces to the Islamic State

terrorist group (also known as ISIS). Zelensky called for the UN Security

Council to expel Russia, a permanent member.

Remarkably, however,

the two sides continued to work around the clock on a treaty that Putin and

Zelensky were supposed to sign during a summit to be held in the

not-too-distant future.

The sides were

actively exchanging drafts with each other and, it appears, beginning to share

them with other parties. (In his February 2023 interview, Bennett reported

seeing 17 or 18 working drafts of the agreement; Lukashenko also reported

seeing at least one.) We have closely scrutinized two of these

drafts, one that is dated April 12 and another dated April 15, which

participants in the talks told us was the last one exchanged between the

parties. They are broadly similar but contain important differences—and both

show that the communiqué had not resolved some key issues.

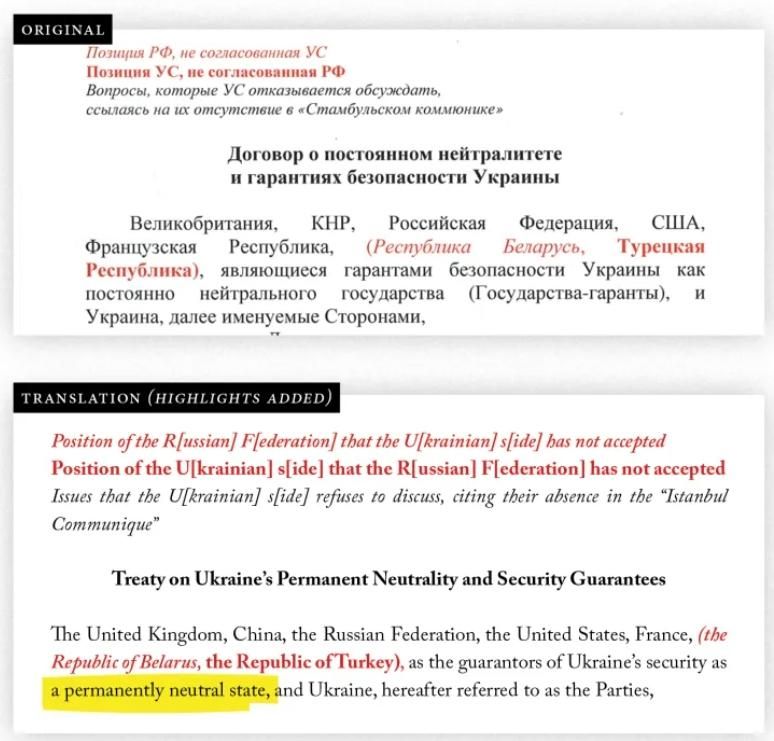

Excerpt of a draft Russian-Ukrainian treaty dated

April 15, 2022

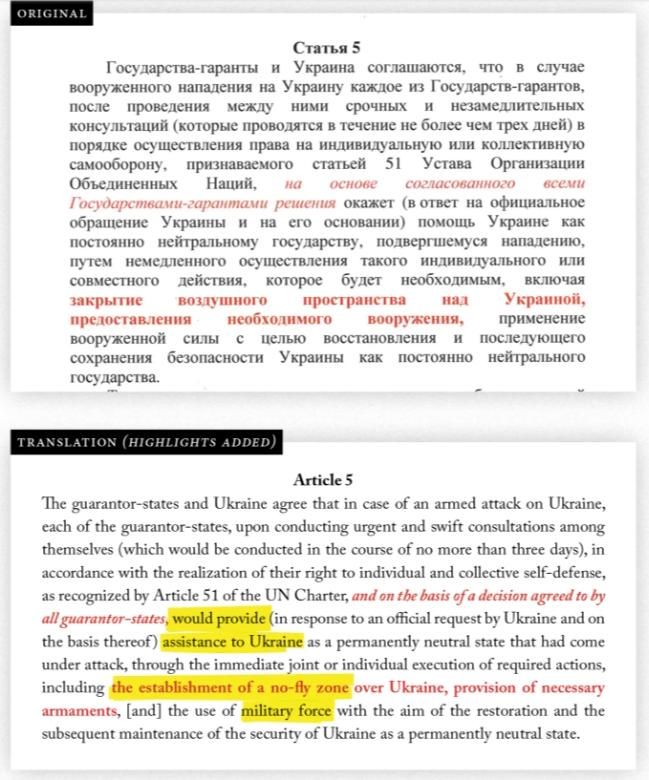

First, whereas the

communiqué and the April 12 draft made clear that guarantor states would decide

independently whether to come to Kyiv’s aid in the event of an attack on

Ukraine, in the April 15 draft, the Russians attempted to subvert this crucial

article by insisting that such action would occur only “on the basis of a

decision agreed to by all guarantor states”—giving the likely invader, Russia,

a veto. According to a notation on the text, the Ukrainians rejected that

amendment, insisting on the original formula, under which all the guarantors

had an individual obligation to act and would not have to reach consensus

before doing so.

Excerpt of a draft

Russian-Ukrainian treaty dated April 15, 2022. Red text in italics represents

Russian positions not accepted by the Ukrainian side; red text in bold

represents Ukrainian positions not accepted by the Russian side.

Second, the drafts contain

several articles that were added to the treaty at Russia’s insistence but were

not part of the communiqué and related to matters that Ukraine refused to

discuss. These require Ukraine to ban “fascism, Nazism, neo-Nazism, and

aggressive nationalism”—and, to that end, to repeal six Ukrainian laws (fully

or in part) that dealt, broadly, with contentious aspects of Soviet-era

history, in particular the role of Ukrainian nationalists during World War II.

It is easy to see why

Ukraine would resist letting Russia determine its policies on historical

memory, particularly in the context of a treaty on security guarantees. And

the Russians knew these provisions would make it more difficult for

the Ukrainians to accept the rest of the treaty. They might, therefore, be seen

as poison pills.

It is also possible,

however, that the provisions were intended to allow Putin to save face. For

example, by forcing Ukraine to repeal statutes that condemned the Soviet past

and cast the Ukrainian nationalists who fought the Red Army during World War II

as freedom fighters, the Kremlin could argue that it had achieved its stated

goal of “denazification,” even though the original meaning of that phrase may

well have been the replacement of Zelensky’s government.

In the end, it

remains unclear whether these provisions would have been a deal-breaker. The

lead Ukrainian negotiator, Arakhamia, later downplayed their importance. As he

put it in a November 2023 interview on a Ukrainian television news program,

Russia had “hoped until the last moment that they [could] squeeze us to sign

such an agreement, that we [would] adopt neutrality. This was the biggest thing

for them. They were ready to finish the war if we, like Finland [during the

Cold War], adopted neutrality and undertook not to join NATO.”

The size and the

structure of the Ukrainian military were also the subject of intense

negotiation. As of April 15, the two sides remained quite far apart on the

matter. The Ukrainians wanted a peacetime army of 250,000 people; the Russians

insisted on a maximum of 85,000, considerably smaller than the standing army

Ukraine had before the invasion in 2022. The Ukrainians wanted 800 tanks; the

Russians would allow only 342. The difference between the range of missiles was

even starker: 280 kilometers, or about 174 miles, (the Ukrainian position) and

a mere 40 kilometers, or about 25 miles, (the Russian position).

The talks had

deliberately skirted the question of borders and territory. Evidently, the idea

was for Putin and Zelensky to decide on those issues at the planned summit. It

is easy to imagine that Putin would have insisted on holding all of the

territory that his forces had already occupied. The question is whether

Zelensky could have been convinced to agree to this land grab.

Despite these

substantial disagreements, the April 15 draft suggests that the treaty would be

signed within two weeks. Granted, that date might have shifted, but it shows

that the two teams planned to move fast. “We were very close in mid-April 2022

to finalizing the war with a peace settlement,” one of the Ukrainian

negotiators, Oleksandr Chalyi, recounted at a public appearance in December 2023. “[A]

week after Putin started his aggression, he concluded he had made a huge

mistake and tried to do everything possible to agree with Ukraine.”

What Happened?

So why did the talks

break off? Putin has claimed that Western powers intervened and spiked the deal

because they were more interested in weakening Russia than in ending the war.

He alleged that Boris Johnson, who was then the British prime minister, had

delivered the message to the Ukrainians, on behalf of “the Anglo-Saxon world,”

that they must “fight Russia until victory is achieved and Russia suffers a

strategic defeat.”

The Western response

to these negotiations, while a far cry from Putin’s caricature, was certainly

lukewarm. Washington and its allies were deeply skeptical about the prospects

for the diplomatic track emerging from Istanbul; after all, the communiqué sidestepped

the question of territory and borders, and the parties remained far apart on

other crucial issues. It did not seem to them like a negotiation that was going

to succeed.

Moreover, a former

U.S. official who worked on Ukraine policy at the time told us that the

Ukrainians did not consult with Washington until after the communiqué was

issued, even though the treaty it described would have created new legal

commitments for the United States—including an obligation to go to war with

Russia if it invaded Ukraine again. That stipulation alone would have made the

treaty a nonstarter for Washington. So instead of embracing the Istanbul

communiqué and the subsequent diplomatic process, the West ramped up military

aid to Kyiv and increased the pressure on Russia, including through an

ever-tightening sanctions regime.

The United Kingdom

took the lead. Already on March 30, Johnson seemed disinclined toward

diplomacy, stating that instead “we should continue to intensify sanctions with

a rolling program until every single one of [Putin’s] troops is out of

Ukraine.” On April 9, Johnson turned up in Kyiv —the first foreign leader to

visit after the Russian withdrawal from the capital. He reportedly told Zelensky that he thought that “any deal with

Putin was going to be pretty sordid.” Any deal, he recalled saying, “would be

some victory for him: if you give him anything, he’ll just keep it, bank it,

and then prepare for his next assault.” In the 2023 interview, Arakhamia

ruffled some feathers by seeming to hold Johnson responsible for the outcome.

“When we returned from Istanbul,” he said, “Boris Johnson came to Kyiv and said

that we won’t sign anything at all with [the Russians]—and let’s just keep

fighting.”

Since then, Putin has

repeatedly used Arakhamia’s remarks to blame the West for the collapse of the

talks and demonstrate Ukraine’s subordination to its supporters.

Notwithstanding Putin’s manipulative spin, Arakhamia was pointing to a real

problem: the communiqué described a multilateral framework that would require

Western willingness to engage diplomatically with Russia and consider a genuine

security guarantee for Ukraine. Neither was a priority for the United States

and its allies at the time.

In their public

remarks, the Americans were never quite so dismissive of diplomacy as Johnson

had been. But they did not appear to consider it central to their response to

Russia’s invasion. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defense

Lloyd Austin visited Kyiv two weeks after Johnson, mostly to coordinate greater

military support. As Blinken put it at a press conference afterward, “The

strategy that we’ve put in place—massive support for Ukraine, massive pressure

against Russia, solidarity with more than 30 countries engaged in these

efforts—is having real results.”

Still, the claim that

the West forced Ukraine to back out of the talks with Russia is baseless. It

suggests that Kyiv had no say in the matter. True, the West’s offers of support

must have strengthened Zelensky’s resolve, and the lack of Western enthusiasm

does seem to have dampened his interest in diplomacy. Ultimately, however, in

his discussions with Western leaders, Zelensky did not prioritize the pursuit

of diplomacy with Russia to end the war. Neither the United States nor its

allies perceived a strong demand from him for them to engage on the diplomatic

track. At the time, given the outpouring of public sympathy in the West, such a

push could well have affected Western policy.

Zelensky was also

unquestionably outraged by the Russian atrocities at Bucha and Irpin, and he

probably understood that what he began to refer to as Russia’s “genocide” in

Ukraine would make diplomacy with Moscow even more politically fraught. Still,

the behind-the-scenes work on the draft treaty continued and even intensified

in the days and weeks after the discovery of Russia’s war crimes, suggesting

that the atrocities at Bucha and Irpin were a secondary factor in Kyiv’s

decision-making.

The Ukrainians’

newfound confidence that they could win the war also clearly played a role. The

Russian retreat from Kyiv and other major cities in the northeast and the

prospect of more weapons from the West (with roads into Kyiv now under

Ukrainian control) changed the military balance. Optimism about possible gains

on the battlefield often reduces a belligerent’s interest in making compromises

at the negotiating table.

Russian and Ukrainian negotiators meeting in Istanbul,

March 2022

And then there is the

Russian side of the story, which is difficult to assess. Was the whole

negotiation a well-orchestrated charade, or was Moscow seriously interested in

a settlement? Did Putin get cold feet when he understood that the West would

not sign on to the accords or that the Ukrainian position had hardened?

Even if Russia and

Ukraine had overcome their disagreements, the framework they negotiated in

Istanbul would have required buy-in from the United States and its allies. And

those Western powers would have needed to take a political risk by engaging in

negotiations with Russia and Ukraine and to put their credibility on the line

by guaranteeing Ukraine’s security. At the time, and in the intervening two

years, the willingness either to undertake high-stakes diplomacy or to truly

commit to come to Ukraine’s defense in the future has been notably absent in

Washington and European capitals.

A final reason the

talks failed is that the negotiators put the cart of a postwar security order

before the horse of ending the war. The two sides skipped over essential

matters of conflict management and mitigation (the creation of humanitarian

corridors, a cease-fire, troop withdrawals) and instead tried to craft

something like a long-term peace treaty that would resolve security disputes

that had been the source of geopolitical tensions for decades. It was an

admirably ambitious effort—but it proved too ambitious.

To be fair, Russia, Ukraine,

and the West had tried it the other way around—and also failed miserably. The

Minsk agreements signed in 2014 and 2015 following Russia’s annexation of

Crimea and invasion of the Donbas covered minutiae such as the date and time of

the cessation of hostilities and which weapons system should be withdrawn by

what distance. Both sides’ core security concerns were addressed indirectly, if

at all.

This history suggests

that future talks should move forward on parallel tracks, with the

practicalities of ending the war being addressed on one track while broader

issues are covered in another.

Keep It In Mind

On April 11, 2024,

Lukashenko, the early middleman of the Russian-Ukrainian peace talks, called

for a return to the draft treaty from spring 2022. “It’s a reasonable

position,” he said in a conversation with Putin in the Kremlin. “It was an

acceptable position for Ukraine, too. They agreed to this position.”

Putin chimed in.

“They agreed, of course,” he said.

In reality, however,

the Russians and the Ukrainians never arrived at a final compromise text. But

they went further in that direction than has been previously understood,

reaching an overarching framework for a possible agreement.

After the past two

years of carnage, all of this may be so much water under the bridge. But it is

a reminder that Putin and Zelensky were willing to consider extraordinary

compromises to end the war. So if and when Kyiv and Moscow return to the

negotiating table, they’ll find it littered with ideas that could yet prove

useful in building a durable peace. The Way Forward In Ukraine.

For updates click hompage here