By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

What next with Ukraine

An unclassified U.S.

intelligence document details some of the intelligence findings, including

the positioning of what officials say could eventually be 100 battalion

tactical groups, as well as heavy armor, artillery, and other equipment.

Whereby Secretary of State Antony Blinken said. “We

do know that he’s putting in place the capacity to do so in short order should

he so decide.”

As Russian forces mass on the border with Ukraine, U.S. analysts and

politicians argue about Moscow’s intentions. When the U.S. secretary of

defense talks about “the Soviet Union”

potentially invading “Ukraine,” the mistakes are excusable, but the optics

betray a general sense of confusion.

In one crucial way, the Russian approach is equally

confused, and dangerously so. Arguments against the possibility of invasion

argue that it simply wouldn’t be rational, that Russian President Vladimir

Putin must be cognizant of the dangers of a long and bloody war, one in which

the West might well get involved.

Yet many in Russia believe the war would be swift and

easy, because the Ukrainians themselves would join them. For years now, Russian

state propaganda has churned out

stories of

how nightmarish the lives of Ukrainians are. Ukrainians, who recently elected a

Jewish president, are portrayed as having their lives controlled by Nazis,

agents of George Soros (a regular target of

anti-Semitism), and other evil-doers. These stories are further buffeted by

long-standing Russian stereotypes of Ukrainians as their little brothers who

are living in an “artificial

state,”

with the nation portrayed as a byproduct of Soviet bureaucracy, not an organic

nation like Russia itself. Ukrainians are Russia’s “fraternal brothers” and the

two countries are “one people.”

Why Putin believes Ukraine was given to

Russia

When the Cossack officer Bohdan Zinoviy Mykhaylovychl organized a rebellion against Polish rule in

Ukraine between 1648 and 1657, it ultimately led to the transfer of the

Ukrainian lands east of the Dnieper River from Polish to Russian control.1 But

the revolt soon became internationalized, and Khmelnytsky eventually

decided to seek a new protector. In 1654, in the town of Pereiaslav, a group of Cossack officers and their leader

swore allegiance to the new sovereign of Ukraine,

Tsar Aleksei Romanov of Muscovy, the second Romanov

tsar. So ended the first, brief period of Ukrainian independence and

began the long, complex relationship with Russia. In 1954, with great fanfare,

the USSR celebrated the tercentennial of Ukraine’s “reunification” with Russia.

The reality is a little more prosaic. Unlike the Polish king, the tsar was

willing to grant the Cossacks privileged status and recognize their statehood.

Hence Khmelnytsky’s decision to align with

Muscovy. What is striking in the complex Russia-Ukraine relationship is the

constant inveighing of competing for historical narratives.

In 2017, when the separatists in

Southeastern Ukraine declared their independent state, they did so with a

replica of Khmelnytsky’s banner.2

Why

Putin’s beliefs all of the Ukraine “was given” to Russia.

Between the late eighteenth century and 1917, people

who came to identify themselves as Ukrainians lived in both the Russian and

Austro-Hungarian empires. This split historical experience is the basis for

Putin’s claim to Bush that part of Ukraine is in Eastern Europe while most of

it “was given” to Russia. It also explains why forming a unified Ukrainian

national identity has been such a challenge since independence and why some

Ukrainian citizens in the east feel more affinity with Russia than with Ukraine.

A brief period of greater autonomy for the Cossack

Hetmanate ended after Peter the Great defeated the Swedes in 1709 at the Battle

of Poltava, declared himself emperor in 1721, and renamed the tsardom of

Muscovy the Russian Empire, thus signaling the rise of Russia as a significant

European power. Those Ukrainians living under Russian rule were gradually

absorbed into the Russian imperial system, and Cossack self-governing units

were abolished. Russians began to call Ukrainians “little Russians.” In 1768, Catherine

the Great went to war with the Ottoman Empire. For the first time, Russia

gained control over today’s Donbas region in Southeastern Ukraine, the

territory seized by Russian-supported separatists in 2014. Catherine called

these lands, including the Port of Odesa, Novorossiya (New Russia). Russia also

conquered Crimea for the first time. The peninsula had been under Ottoman rule,

and its inhabitants were Muslim Crimean Tatars.

Catherine the Great’s lover,

Prince Grigory Potemkin, who administered these newly acquired

territories, persuaded the tsarina to visit her new conquests. In 1787, she set

out from Saint Petersburg on a six-month trip to Sevastopol in Crimea, covering

more than 4,000 miles by land and water. Potemkin, realizing that the trip had

to be flawless, arranged for all the roofs in villages she passed on the

Dnieper River to be freshly painted, the streets freshly paved, giving rise to

the legend of “Potemkin villages,” or “false fronts covering a gloomy reality.”

3 Catherine was gratified as she traversed the new lands of Ukraine. A

wilderness was waiting to be developed, and Potemkin planned cities on the

Black Sea, attracted foreign colonists to settle in them, and began to create

the fleet that would be his legacy.

As Russia conquered Southeastern Ukraine, the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth began to break apart, ending in 1772 with

Poland’s first of three partitions. Those Ukrainians living in Galicia were now

ruled from Vienna and were called Ruthenians in most Austro-Hungarian Empire

and Rusyns in the Transcarpathia region. By 1795, ethnic Ukrainians were

divided between Dnieper Ukraine under the Russian tsars, where 85 percent

lived, and Austria-Hungary. The social and cultural development of ethnic

Ukrainians between the late eighteenth century and the Bolshevik Revolution

diverged widely. Galician Ukrainians in Western Ukraine preserved their

language and customs more than those Dnieper Ukrainians under imperial Russian

rule in the east. They began to develop a distinct national consciousness,

participating in the revolutions of 1848 and declaring their autonomy. For the

next half-century, this consciousness grew. In imperial Russia, by contrast,

there was little effective political activity on behalf of ethnic Ukrainians,

nor was the Ukrainian language well developed. Most Russians did not consider

Ukrainians a separate ethnicity. After the 1905 revolution, the first

Ukrainian-language journal appeared in Kyiv. Ukrainians gained a few dozen

seats in the new Duma, promoting Ukrainian causes. But the tsar soon dissolved

the Duma and ended these endeavors.

Revolution, war, famine, and war again.

Vladimir Lenin promised the non-Russian ethnic groups

living in the empire that if the revolution came, they would achieve

independence. In March 1917, after the tsar’s abdication, representatives of

Ukrainian political and cultural organizations in Kyiv composed a coordinating

body, the Central Rada. The revolution came in October 1917, and the Ukrainians

took Lenin at his word. Following the Bolshevik coup, the Rada proclaimed the

Ukrainian People’s Republic and, in January 1918, declared Ukraine’s independence.

Thus began Ukraine’s second, a brief period of Freedom from Russia during the

chaotic post-revolutionary period and the civil war. The collapse of the

Austro-Hungarian Army and the ensuing Russo-Polish War also reunited the

Dnieper and Galician Ukrainians. It led to the proclamation of an independent

Ukrainian state of former Russian-and Austrian-ruled parts of the country in

1919. But the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire also created a new,

independent Polish state.

As the Russo-Polish War intensified, Lenin’s long-term

goal of world revolution was subordinated to the imperatives of military

victory over the Poles. Without Ukrainian bread and coal, that would not be

easy. Ukraine’s rich black earth and abundant grain supplies were indispensable

for a Russian victory. In 1920, the

Poles defeated the Russians and seized lands the fledgling Ukrainian state had

sought to incorporate. By the terms of the March 1921 Treaty of Riga, Poland

took back Galicia, and Ukraine was again divided between Russia, Romania,

Poland, and Czechoslovakia. The question of why Poland and Czechoslovakia were

able to achieve independence after 1918, while Ukraine was not, is partly

answered by the weakness of the Ukrainian national movement and the different

historical trajectories of Galician and Dnieper Ukraine.4

Under Stalin’s rule, Soviet Ukraine experienced a

brief cultural renaissance-- with increased use of the Ukrainian language in

educational institutions. This was soon followed by a dark decade of famine and

violence during collectivization and the purges. When Stalin began his campaign

of forced collectivization of the Soviet countryside, and many peasants

throughout the USSR burned their crops and slaughtered their livestock in acts

of resistance against being herded onto collective farms, the regime singled

out Ukraine for especially harsh treatment. Between 1932 and 1934, increasingly

unrealistic grain requisition quotas were levied on Ukrainian peasants.

Altogether, close to four million people in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist

Republic perished due to the ensuing famine.5 Ukrainians refer to this man-made

famine as the Holodomor, a premeditated act of genocide during which Stalin

deliberately targeted Ukrainians for elimination. Many Russians dispute this

narrative, claiming that Stalin was essentially an equal-opportunity killer and

Soviet-made famines in other parts of the Soviet Union during collectivization.

Ukrainians had barely recovered from the famine and

Stalin’s purges when Germany invaded Poland under the secret terms of the 1939

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, followed shortly thereafter by the USSR invading

Eastern Poland and acquiring the Galician Ukrainian population. In June 1941,

Hitler scrapped his agreement with Stalin, launched Operation Barbarossa, and

invaded the USSR— through Belarus and Ukraine. Ukraine was, for the Nazis, the

ultimate Lebensraum (living space), a territory where racially pure Germans

could escape from the “unhealthy urban society” and build a racially pure

society. This meant, of course, removing the local Slavic population, who they

considered Untermenschen (subhumans).

The Reichskommissar for Ukraine, Erich

Koch, was a particularly brutal leader.6 Nevertheless, given many Ukrainians’

antipathy toward Soviet rule, some of them initially welcomed the Nazi invaders

as liberators and collaborated with them. This, plus the fact that one of their

nationalist leaders, Stepan Bandera, initially allied his organization with the

Nazis, has fueled the current Russian narrative about “Ukrainian fascists”

running the government in Kyiv. Other Ukrainians joined the resistance to the

Nazis. By the time Lieutenant-General Nikita Khrushchev led Red Army troops to

recapture Kyiv in November 1943, Bandera and others had grown disillusioned

with the Germans.

The territorial settlement at the end of World War Two

reunited Galicia and Dnieper Ukraine in the new Ukrainian Soviet Socialist

Republic. Stalin had managed to secure Roosevelt’s ascent to allow Ukraine to

have its own delegation at the United Nations, which gave it international

status. His successor, Nikita Khrushchev, in a seeming act of generosity, made

that decision in 1954 whose consequences he could not possibly have foreseen.

In honor of the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereiaslav,

and celebrating the “great and indissoluble friendship” of the Russian and

Ukrainian people, he transferred Crimea from Russian to Ukrainian jurisdiction,

making it part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.7 At that point

Khrushchev was involved in an ongoing power struggle and he wanted to improve

his support among Ukrainian elites. He did this not just for symbolism and

sentiment but also for practical economic reasons, hoping that Ukraine was in a

better geographic position to help Crimea’s struggling economy. After all,

Ukraine and Crimea were connected by land, whereas Russia had no access by land

to Crimea.8

In the years between Khrushchev’s rise and Gorbachev’s

coming to power, Ukrainians were well integrated into Soviet society, with a

disproportionately high percentage serving in the Soviet armed forces. Much of

the Ukrainian intelligentsia was Russified and co-opted into the Soviet system.

A quarter of the Soviet military-industrial complex was located in Eastern

Ukraine. Periodically nationalist currents would assert themselves, but they

would be suppressed. Mikhail Gorbachev himself embodied this Soviet reality,

with a Ukrainian mother and a Russian father. When he came to power, his calls

for glasnost were not immediately taken up by the more conformist Ukrainian

party leadership. But events soon changed that. In 1986, the nuclear explosion

at Chernobyl, including the initial cover-up that may ultimately have cost

hundreds, if not thousands, of lives in Ukraine and the subsequent admission of

guilt by the Soviet authorities, mobilized public opinion.9 Between 1986 and

1991, different Ukrainian nationalist groups organized themselves, pressuring

for greater autonomy and, ultimately, for independence. Although much of the

Ukrainian party ruling nomenklatura were reluctant nationalists, they were

caught up in an accelerating process of state collapse as Soviet citizens took

Gorbachev at his word and insisted on self-determination.

When asked at a lecture in the Library of Congress

some years after the Soviet collapse what his greatest mistake had been,

Gorbachev paused and said, “I underestimated the nationalities question.” Ever

since the tsarist empire began to expand, eventually comprising more than one

hundred different ethnic groups, the rulers’ challenge was to maintain

centralized control over this complex mosaic of languages, cultures, and

religions. The default instinct was Russification, the imposition of Russian

language and culture on the population, which produced a counter-reaction and

mobilized non-Russian groups to join the Bolsheviks. Eventually, history

repeated itself seventy-four years later. Like Soviet leaders before him,

Gorbachev believed that the federal Soviet state, which had existed since 1922,

had resolved the national question by granting limited cultural autonomy to

different ethnic groups. This was especially true of Ukraine, viewed as the

cradle of Russian history.

But in the end, Ukraine was instrumental in the

collapse of the USSR. Throughout 1990 and 1991 Gorbachev sought to negotiate a

new union treaty that would have held the USSR together by granting more

autonomy for the union republics. How different things might have turned out

had he succeeded. But just before the vote on a new treaty, a group of

disgruntled hard-line officials staged a

coup against Gorbachev while he was on vacation in Crimea. Shortly after the

August 1991 putsch collapsed, Ukraine’s top legislative body the Supreme

Soviet, under the leadership of party chief Leonid Kravchuk, declared its

independence, much to Gorbachev’s dismay.

He was not the only official to oppose the Ukrainian

move. President George H. W. Bush did everything he could to keep the Soviet

Union alive. The U.S. was very concerned about the security implications of a

potential Soviet collapse because of the USSR’s vast nuclear arsenal. Just

before the coup, in a speech in Kyiv, Bush admonished Ukrainians: “Freedom is

not the same as independence. Americans will not support those who seek

[independence] in order to replace a far-off tyranny with a local despotism. They

will not aid those who promote a suicidal nationalism based upon ethnic

hatred.” 10

Boris Yeltsin’s hunting lodge meeting

In December 1991, the Ukrainian people voted in a referendum for

independence: 90 percent supported independence, including 83 percent in

the Donetsk region and 54 percent of the population of Crimea. Shortly

thereafter, Boris Yeltsin met with Kravchuk and Belarusian

leader Stanislau Shushkevich in the hunting lodge in the Belavezha Forest outside Minsk. What happened at that

meeting? What promises were made? Revisionist interpretations of this meeting

have fueled the current Russian narrative about Crimea. While the Russian

delegation arrived with proposals for a reformed Slavic union, Kravchuk was

determined that Ukraine emerge from the meeting with its independence. On the

first night, dinner was dominated by a vigorous debate about whether some form

of a union could be preserved. Kravchuk argued with Yeltsin about whether the USSR

should be completely dissolved. In the end, after two days of intense

discussions, the three leaders emerged with a handwritten document (there were

no typewriters in the hunting lodge) that dissolved the USSR.

The agreement on establishing a Commonwealth of

Independent States (CIS) consisted of fourteen articles. The three leaders

agreed to recognize the territorial integrity and existing borders of each

independent state. So ended seventy-four years of Soviet rule. Andrei Kozyrev,

Yeltsin’s foreign minister, called George H. W. Bush to give him the news. As

for Gorbachev, he was furious: “What you have done behind my back with the

consent of the U.S. president is a crying shame, a disgrace,” he told Yeltsin.11

Almost from the beginning, Russians began to question

the legality of the hastily written agreement. They hinted that a secret

addendum would have permitted changes in borders where the local population to

decide this by referendum. What is indisputable is that Kravchuk’s refusal to sign a new union

treaty led to the Soviet Union’s demise. For that reason, some Russians

blame Ukraine for precipitating what Putin has called “a major geopolitical

disaster of the twentieth century.” 12

Nuclear weapons, the disposition of the

Black Sea Fleet, and Crimea.

The three signatories to the treaty that ended the

USSR termed it a “civilized divorce.” But as the 1990s wore on, the

Russian-Ukrainian divorce became increasingly acrimonious. Yeltsin’s main

objective in convening the meeting that dissolved the USSR had been to oust

Gorbachev from the Kremlin. He had not thought through the implications of

ushering in an independent Ukrainian state. Four years later, it became clear

that Yeltsin was having second thoughts about the security implications of the

Soviet breakup. A September 1995 presidential decree, laying out Russia’s

security interests in the CIS and the imperative of protecting the rights of

Russians living there, stated that “this region is first of all Russia’s zone

of influence.” 13 Almost from the beginning, Russian officials sought to

reinforce that decision by using the extensive financial, trade, personal,

political, and intelligence networks that bound the two societies together to

undermine Ukrainian sovereignty and strengthen dependence on Moscow. The

Russian Duma, even in its early, more pluralistic incarnation, intervened on

several occasions to declare that Crimea was Russian, backed by Moscow’s

powerful and outspoken mayor Yuri Luzhkov, who had extensive personal

investments on the peninsula. Domestic developments inside Ukraine served to

facilitate these Russian endeavors. In the 1990s, Ukraine developed a more

pluralistic political system than that in Russia but one ruled by corrupt,

oligarchic clans that failed to build transparent institutions of government

and law strong enough to resist Russian meddling. The energy sector was

particularly corrupt, with opaque middlemen, both Ukrainian and Russian,

amassing fortunes from the transit system that carried Russian gas to Europe

via Ukraine.14

Three issues dominated Russia-Ukraine relations in the

1990s: nuclear weapons, the disposition of the Black Sea Fleet, and Crimea.

When the USSR collapsed, Ukraine was the world’s third largest nuclear state

after the United States and Russia, with one-third of the Soviet nuclear

arsenal and significant capacities in design and production. It had 2,000

strategic nuclear warheads and 2,500 tactical nuclear weapons. Immediately

after the Soviet collapse, the fate of Ukraine’s nuclear arsenal became an urgent

matter for U.S. policymakers. The prospect of “loose nukes” set off alarms in

the White House. The issue dominated Washington’s policy toward Ukraine during

the last year of the George H. W. Bush administration and the first years of

the Clinton administration.15 The United States was determined that Russia be

the only nuclear state in the post-Soviet space. That meant Ukraine, Belarus,

and Kazakhstan (the latter two also had nuclear weapons on their territories)

should transfer their warheads and delivery systems to Russia, which would

destroy them. Initially, Washington wanted Russia to handle the negotiations

with its three post-Soviet neighbors, but that proved impossible. So, in the

end, the United States negotiated with all four states to accomplish denuclearization.

At the end of the USSR, acrimonious rhetoric was

exchanged between Ukrainian and Russian officials, parliamentarians, and

commentators; there was a concern that war-- perhaps even a nuclear conflict--

might break out. Hence the urgency the West felt to move the nuclear weapons

out of Ukraine. The new Ukrainian government, suspicious of Yeltsin’s

longer-term intentions, asked the Americans to give it security guarantees

similar to those of NATO members-- namely that the United States would come to

Ukraine’s assistance was it attacked by another power. But American officials

realized that was impossible and proposed that Russia also provide Ukraine with

security assurances. And so, after an arduous negotiation process, the U.S.

insisted on using the word “assurances” instead of “guarantees” in the legal

document that accompanied Ukraine’s denuclearization. “Assurance” implies a

lesser commitment than “guarantee.” Here is where translation fails. The

problem is that both Russian and Ukrainian use the same word for guarantee and

assurance, leaving room for misinterpretation.

In January 1994, Bill Clinton had to twist the arms of

both Yeltsin and Kravchuk to sign a trilateral agreement on the disposition of

Ukraine’s nuclear weapons.16 He met with them in Moscow wearing a button that

reads “Carpe Diem” (Seize the Day).17 In December of that year, the deed was

finalized in Hungary with the new Ukrainian president, Leonid Kuchma. The

Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances was signed by the United States, the

United Kingdom, and Russia. The three signatories agreed to “respect the

independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine,” “to refrain

from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political

independence of Ukraine,” and “to seek immediate United Nations Security

Council action to provide assistance to Ukraine… if Ukraine should become a

victim of an act of aggression.” 18

In June 1996, two trains carrying the last strategic

nuclear warheads departed Ukraine and arrived in Russia, where the warheads

were delivered to a dismantlement facility. Ukraine had given up its nuclear

weapons in return for security “assurances” from Russia, the United States, and

the United Kingdom. Just how credible these were became clear in March 2014,

when neither the United States nor the United Kingdom came to Ukraine’s

assistance after Russia’s military incursion into Crimea and later into the Donbas

region. Nor was the United Nations able to intervene, because of Russia’s veto

in the Security Council. The Budapest Memorandum was a dead letter, a lesson

not lost on either advocates of nonproliferation or states aspiring to become

nuclear powers. Giving up nuclear weapons makes a country vulnerable to outside

aggression.

The Black Sea Fleet was the second most contentious

issue between Russia and Ukraine. The former jewel in Russia’s naval crown,

created by Prince Potemkin and headquartered in Sevastopol, Crimea, was, in the

words of the nineteenth-century London Times, “the heart of Russian power in

the East.” The fleet had 350 ships and 70,000 sailors at the time of the Soviet

collapse.19 Russia was determined to maintain its naval presence in Crimea.

Ukraine, which had a $ 3 billion debt to Russia, mainly to Gazprom, was not in

a strong bargaining position. Although Yeltsin himself understood that a

compromise had to be found, he was battling his Supreme Soviet, which called

for “a single, united, glorious Black Sea Fleet.” 20 In the immediate

post-Soviet years, the situation was tense, as Russian and Ukrainian commanders

challenged each other by raising, and then taking down, each other’s flags on

their ships. Ukraine did not have the wherewithal to take over the fleet

completely, and Russia would never have acquiesced to that. After a series of

protracted negotiations, Yeltsin and Kuchma eventually signed an agreement in

1997 dividing the fleet. Russia agreed to lease basing facilities in Crimea,

principally in Sevastopol, for its Black Sea Fleet until 2017 and would pay for

the lease by forgiving part of Ukraine’s debt. When Viktor Yanukovych was

elected president in 2010, he extended the Russian lease until 2042.

Closely tied to the Black Sea Fleet issue was the dispute

over Crimea. At the time of the Soviet breakup, ethnic Russians constituted 60

percent of the peninsula’s population and 70 percent of the population in

Sevastopol, home to the Black Sea Fleet. For the first half of the 1990s,

Russian lawmakers would vote to reincorporate Crimea into the Russian

Federation, and local leaders in Crimea would declare independence from

Ukraine. In May 1992, the Russian parliament declared illegal Khrushchev’s 1954

transfer of Crimea to Ukraine, and the Crimean legislature scheduled an

independence referendum-- with Moscow’s approval. Eventually, Crimea was

granted the status of an autonomous republic inside Ukraine with considerable

self-rule powers. But the peninsula began to suffer from economic neglect. “The

Palm Springs of the Soviet Union has now become the Coney Island of Ukraine,”

said a U.S. official.21

In 1997, Yeltsin and Kuchma signed the Treaty of

Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership Between the Russian Federation and

Ukraine. The treaty codified the border, and both sides agreed to work toward a

strategic partnership. It was Yeltsin’s first official visit to Kyiv as Russian

president, and he sounded a conciliatory note: “We respect and honor the

territorial integrity of Ukraine.” 22 At this point Russia appeared to have

reluctantly reconciled itself to the independence of a Ukraine that included Crimea.

The treaty in retrospect represented the high point of Ukraine-Russia relations

in the post-Soviet era. Once Putin came to power, things began to change.

The Orange revolution and the gas wars

When Putin entered the Kremlin in 2000, Ukraine’s

president, Leonid Kuchma, was steering a careful course between Russia and the

West. Putin traveled to Kyiv shortly after becoming president and praised the

relationship with Ukraine while pointedly noting Kyiv’s outstanding gas debt to

Russia.

The two presidents traveled to Sevastopol, boarded

flagships of both their navies and Putin acknowledged Ukraine’s sovereignty

over both Sevastopol and Crimea. It appeared to be a promising start to

relations. Privately, however, Ukrainian officials expressed wariness about

this unknown Kremlin leader with a KGB past.23

Ukraine’s domestic situation under Kuchma suited

Moscow. Economic reform had stalled, oligarchic capitalism and corruption were

on the rise, and the gas trade was arguably the most corrupt element in a

system that united Russian and Ukrainian magnates. Eighty percent of Russia’s

gas exports to Europe went through Ukraine. The gas trade, including gas

purchased from Central Asia and then re-exported to Europe via Ukraine, was in

the hands of an opaque middleman company jointly owned by Russians and Ukrainians,

RosUkrEnergo (RUE). There was no “us versus them” in the gas trade, and both

Russians and Ukrainians amassed large fortunes from RUE.24 Ukraine’s weak

institutions, a floundering economy, and corrupt political system left it

vulnerable to Russian influence. Moreover, financial and intelligence networks

from the Soviet period that connected Ukrainians and Russians had survived the

Soviet collapse. When Kuchma was implicated in the murder of investigative

journalist Georgiy Gongadze, the United States demanded an

unbiased inquiry. The Kremlin never criticized Kuchma for

undemocratic practices.

But the people of Ukraine had a different view. They

became increasingly frustrated with their government and its lack of

accountability. In the lead-up to the 2004 presidential election, they were

determined to choose a more accountable leader. Kuchma’s chosen successor was

Viktor Yanukovych, a former juvenile delinquent from the Donetsk region who

represented the pro-Russian part of Ukraine and spoke Russian. His main rival

was Viktor Yushchenko, former central bank governor with an American wife,

whose first language was Ukrainian and who represented Ukraine’s pro-Western

forces. Unlike in Russia, elections in Ukraine were not “managed” and the

outcome was not predetermined. The election campaign became a contest between

Russia and the West. Ukraine occupied a key place in Putin’s foreign policy

priorities, and he was determined that Yanukovych win. The Kremlin also

mistakenly believed that tactics that had worked well in manipulating Russia’s

own elections would be equally effective in Ukraine. But, in the words of

outgoing president Kuchma, “Ukraine is not Russia.” 25

In July 2004, Putin effectively endorsed Yanukovych in

a meeting with Kuchma. Indeed, during a visit with Putin in May, Secretary of

State Condoleezza Rice was introduced to Yanukovych and the implication was

clear: the Russian leader was communicating that he had the power to choose the

next Ukrainian leader.26 Shortly thereafter, Gleb Pavlovsky, a

Kremlin-connected “political technologist” established a “Russian club” in Kyiv

aimed at promoting Yanukovych and denigrating Yushchenko through aggressive

media tactics. The Kremlin also offered a series of economic and political

concessions to convince the Ukrainian people of the importance of cooperation

with Russia. 27

The U.S. government, by contrast, did not endorse

either candidate but stressed the importance of a fair, free, transparent

election. Nev, U.S. NGOs, in cooperation with European civil society U.S. NGOs

groups, were involved in training Ukrainian groups in activities such as

parallel vote counting and election monitoring. Many U.S. officials and

democracy-promotion organizations saw the Ukraine election as a test case for

political transformation in the post-Soviet space, and the Kremlin understood

this as a direct challenge to its influence in this neighborhood. The Soros

Foundation contributed $ 1.3 million to Ukrainian NGOs, and USAID gave $ 1.4

million for election-related activities, including training the Central

Election Commission.28 Russian commentators-- betraying a profound

misunderstanding of how the U.S. system worked-- later conflated Soros and

George Bush as jointly promoting regime change in Ukraine, apparently not

realizing that in 2004 Soros was spending large sums of money in the U.S. to defeat

Bush in the upcoming U.S. election. But U.S. public relations firms were also

working to burnish Yanukovych’s credentials. Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign

manager in 2016, who resigned after his Ukrainian and Russian connections were

exposed and was subsequently jailed as part of the Mueller investigations into

the 2016 U.S. election, was hired by Yanukovych in 2004 to assist in his

election campaign.29

The results of the first round of elections were

inconclusive. During the interim between the first and second round, Putin

personally campaigned for Yanukovych. The day after the second round, on

November 22, 2004, Putin congratulated Yanukovych on his win— before the

results were announced. He was duly proclaimed the winner. But all the exit

polls and NGO parallel vote counting pointed to a rigged vote count, indicating

that the real victor was indeed Yushchenko. Thousands of Ukrainians began

congregating in sub-zero temperatures in Kyiv’s snow-covered central Maidan

Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), demanding a rerun of the election.

Protestors blocked access to government buildings, effectively shutting down

the government for weeks. The stalemate ended when U.S. secretary of state

Colin Powell chose sides for the West and announced, “We cannot accept the

Ukraine election as legitimate.” 30 Thereafter, Polish president Alexander

Kwasniewski and Lithuanian president Valdas Adamkus led

a mediation process that resulted in a rerun of the election

and Yushchenko’s victory. Four months after his installation as

president, he visited Washington, spoke to a joint session of Congress, and

received a standing ovation.

Moscow’s candidate had lost and Washington’s had won--

at least that is how the Kremlin saw the Orange Revolution. Putin had invested

personal and political capital in backing Yanukovych but had not prevailed. For

Putin, Ukraine now represented a double challenge-- to Russian foreign policy

interests and to the survival of the regime

itself. Yushchenko’s desire to move toward the West threatened

Russia’s political and economic ties with and influence over its most important

neighbor. But equally threatening was the specter of the Ukrainian people

protesting against a corrupt, repressive government and bringing it down. Hence

it was convenient to blame the United States for pursuing regime change in

Ukraine. For example, Sergei Markov, one of the Kremlin’s “political

technologists,” told an international audience in May 2005, “The CIA paid every

demonstrator on the Maidan ten dollars a day to protest.” 31 The Kremlin made

similar comments a decade later when the next major Maidan upheaval occurred.

As Putin told the friendly American filmmaker Oliver Stone, after the Orange

Revolution, “We saw the West expanding their political power and influence in

those territories, which we considered sensitive and important for us to ensure

our global strategic security.” 32

Putin’s relationship

with Yushchenko and Yushchenko’s one-time ally and then

opponent Yulia Tymoshenko remained tense for the next five

years. The battle of historical

narratives between Russia and Ukraine resurfaced, challenging the legitimacy of

Russia’s claims. The new government revived all the arguments about

Ukrainian historical identity, introducing a far more critical stance toward

Russia’s role. The Holodomor-- Stalin’s man-made famine in the early 1930s--

was commemorated as a Soviet genocide against the Ukrainian people. Stepan

Bandera, the wartime Nazi collaborator, was posthumously and controversially

designated a “Hero of Ukraine.” Yushchenko spent much of his time

traveling to Europe, seeking assistance from the E.U. and NATO, and promising

economic and legal reforms. His conflicts with Prime

Minister Tymoshenko ultimately led to a stalemated reform agenda and

increasing Ukrainian and Western frustration with his government. Meanwhile,

many of the old ties between Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs and security

service personnel remained. Ukrainians who had flocked to the Maidan became

disillusioned with the Orange government because its leaders spent more time

abroad or quarreling with each other than implementing real reforms.

When Yushchenko came into office, Ukraine rated 122nd on Transparency

International’s corruption perception index. When he left office, it was ranked

at 146th, on a par with Zimbabwe.33

Throughout this period, Russia retained a major source

of leverage over Ukraine: the gas trade. After Yushchenko’s election,

Gazprom engaged in tough negotiations with Kyiv over the price it would pay for

Russian gas. Ukraine has one of the least energy-efficient economies in the

developed world. Gas from Russia was heavily subsidized, and Kyiv paid

one-third the price for Russian gas as Europe. As Putin said in 2005, if

Ukraine wanted to join the West, why should Russia subsidize its energy? As the

December 31, 2005, deadline for agreeing on a new price approached, the

Ukrainians refused Gazprom’s latest offer. On January 1, 2006, Gazprom turned off the gas tap to Ukraine

without informing its customers in Europe, leaving many along the pipeline

route without heat in freezing temperatures. But the Kremlin miscalculated.

Ukraine siphoned off supplies destined for Europe, and the Europeans blamed

Russia for their shortages. Three years later, in 2009, Gazprom repeated the

cutoff after another price dispute, but Europe was better prepared this time,

having stored gas reserves. Nevertheless, Russia’s energy leverage over Ukraine

continued to limit Kyiv’s Freedom to maneuver throughout

the Yushchenko presidency.

Crimia’s seizure and the break with the

West

In January 2010, Ukraine went to the polls in a presidential election viewed as a

referendum on the Orange Revolution. Tymoshenko and Yanukovych

were the main contenders, and Yanukovych emerged victorious after the second

round. With the Obama administration pursuing its reset with Russia, Washington

had no desire to have Ukraine as a contentious issue in US-Russia relations and

decided to try to work with the new Yanukovych government. The Kremlin,

needless to say, welcomed Yanukovych’s election, particularly since he said

that his first priority was to improve ties to Russia and that Ukraine would

not seek NATO membership. During his first months in office, he reversed

Yushchenko-era policies that angered Moscow, such as the designation of

Holodomor as a genocide, the praise for Bandera and his colleagues, and the

de-emphasis on the Russian language. From Putin’s point of view, Russia now had

an opportunity to reassert its influence over Ukraine.

But Yanukovych was not an easy client. He also

continued to seek closer ties with the European Union, something the oligarchs

from Eastern Ukraine-- who supported him-- favored because they wanted better

access to European markets for their metals and industrial equipment. The Obama

administration decided to scale back its involvement in Ukraine and let its

European allies focus on encouraging Ukraine to commit to a reform program.

After Yanukovych became president, he began negotiations with the E.U. for an

Association Agreement and a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement. The

E.U. bureaucrats who carried out these negotiations focused on technical

details, perhaps failing to comprehend the broader geopolitical impact of their

actions, so there was little consideration given to how Moscow might. However,

it is also true that Moscow rebuffed several E.U. attempts to bring it into

these discussions. Initially, the Kremlin appeared to be indifferent to these

talks. But as the negotiations neared their conclusion in 2013, the Kremlin

began to focus more intensely on the content of the E.U. agreements. A critical

point came when it realized they were much more far-reaching than Russia had

originally understood. If Ukraine signed them, it could not join the Eurasian

Economic Union and its economic relationship with Russia would be disrupted.

The economies of Russia and Ukraine, especially Eastern Ukraine, are quite

interdependent, and the E.U. was offering Ukraine a deal that involved a great

deal of economic pain while reforms were implemented in return for a more

prosperous economy somewhere further down the road.

Once the Kremlin understood the full

implications of the E.U. deal, it sprung into

action. Russia used a mixture of sticks, including preventing Ukrainian trucks

from crossing the border to deliver goods into Russia and carrots to dissuade

Yanukovych from signing the Association Agreement. They worked. On November 21,

2013, Ukraine announced that it had suspended its talks with the E.U.34 At the

November 28– 29 E.U. summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, where Ukraine had been

expected to sign the agreement, Yanukovych pulled out. 35 Soon after that, it

was announced that Moscow would loan Ukraine $ 15 billion to bail out its

faltering economy. The Kremlin breathed a sigh of relief. It had stopped

Ukraine from moving closer to the E.U. But Putin had not reckoned with the

Ukrainian street, which had mobilized to oust Yanukovych almost a decade

earlier. Since his election in 2010, his administration had become increasingly

corrupt. Symbolic of the regime’s excesses were his palatial estate north of

Kyiv, which housed a zoo with wild boars and a mansion with ornate furnishings,

marble staircases, vintage automobiles, and golden toilets. 36 Even though the

palace was only opened to the public after his flight from Ukraine, Ukrainians

understood the scale of corruption under which they were living, for them,

signing an agreement with the E.U. meant committing to a more democratic, less

corrupt Ukraine. So when they once again poured into Kyiv’s central square in

protest, they called their movement EuroMaidan. Three days after Yanukovych’s

announcement, 100,000 protestors went out into the streets of Kyiv.

For the next three months, the number of

protestors in Maidan grew to 800,000, demanding that Yanukovych change course.

Protestors ranged from pro-Western liberals to right-wing nationalists, and as

the demonstrations continued, the government’s response became more violent. 37

U.S. assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian Affairs Victoria

Nuland and Senator John McCain both visited the protestors in the Maidan and

offered food and support. U.S. secretary of state John Kerry expressed “disgust

with the decision of the Ukrainian authorities to meet the peaceful protest in

Kyiv’s Maidan Square with riot police, bulldozers, and batons rather than with

respect for democratic rights and human dignity.” 38 “Yanukovych,” wrote one

eyewitness, “claimed to the Western media that Maidan was filled with fascists

and anti-Semites, while telling his own riot police that the Maidan was filled

with gays and Jews.” 39 Things came to a head between February 18 and 20, 2014,

when Ukrainian special forces and Interior Ministry snipers launched an attack

on the Maidan, eventually killing one hundred people and wounding hundreds

more. Today the Maidan commemorates the Heavenly Hundred with a permanent

exhibition of their photographs and biographies lining the outer perimeter of

the square.

Two days later, the German, French, and Polish foreign

ministers arrived to try to broker a settlement between Yanukovych and

opposition politicians. Russia sent former diplomat Vladimir Lukin to

take part, but he did not sign the agreement negotiated by his colleagues. On

February 21, Yanukovych and the leaders of three opposition parties agreed that

presidential elections would be moved up to December 2014, that constitutional

reform would be undertaken, and that there would be an independent investigation

into the slaughter in the Maidan. The E.U. officials left convinced they had

negotiated a compromise to de-escalate the crisis. They were, therefore,

stunned to find out the next day that Yanukovych had fled Kyiv during the

night, eventually turning up in Rostov in Southern Russia a week later.40

Apparently, his security detail had abandoned him when they realized he would

soon be out of power and no longer able to protect them, and he feared for his

safety. It was subsequently ascertained that he had begun packing his

belongings a few days earlier. Shortly thereafter, opposition politicians

announced the formation of a new government and set new presidential elections

for May. In what was a provocative gesture, they also voted to deprive the

Russian language of its official status—although that unwise decision was soon

reversed.

The issue of how and why Yanukovych fled inflamed relations between

the Kremlin and the West. Russia’s version of the facts differed radically from

that of the West. Given that the Kremlin controlled all major Russian news

outlets, it served a unitary and consistent diet of news. A “fascist junta” had

taken over in Kyiv, illegally ousting a democratically elected president.

Russian media excoriated the appearance of posters in Kyiv bearing the picture

of Stepan Bandera. Russians consistently speak of a “coup” in Ukraine,

orchestrated by the U.S. and E.U. The truth is more prosaic. Yanukovych was not

overthrown. He simply fled. While Putin was known to hold Yanukovych in

contempt, he was demonstrating that unlike Obama—who had abandoned such allies

as Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak during

the 2011 revolution in Egypt—he would stand by his allies and welcome them

to Russia.

Nevertheless, Putin was convinced that the United States and its allies were

responsible for Yanukovych’s ouster. Actions by U.S. officials reinforced

this view. Nuland was overheard on a phone call leaked by the Russians bluntly

discussing with the U.S. ambassador in Kyiv which of Yanukovych’s opponents

they should support. Since Putin was already convinced that Washington was out

for regime change in the post-Soviet space, he viewed Yanukovych’s ouster as a

direct threat to Russian interests. It is also likely that he feared the next

Ukrainian president might renege on the deal for the Black Sea Fleet. Moreover,

to have not reacted to the Maidan events and to Yanukovych’s ouster would have

left him looking weak.

A few days after Yanukovych fled, and just after the

Sochi Winter Olympics had ended, President Putin ordered surprise military

exercises of ground and air forces on Ukraine’s doorstep. Suddenly hundreds of

troops with no insignia (“little green men”) began appearing in Crimea. The decision to invade was made

by Putin in consultation with only four advisers: his chief of staff, the head

of the National Security Council, his defense minister, and the head of the

Federal Security Service (FSB). Foreign Minister Lavrov was apparently not

consulted.41 In the name of protecting Russians in Crimea from oppression by

the “illegal fascist junta” in Kyiv, unidentified militiamen took over

Sevastopol’s municipal buildings, raising the Russian flag, and then proceeded

systematically to repeat these moves around Crimea and intimidate the Ukrainian

naval forces in Sevastopol. Ukrainian forces in Crimea, on the advice of the

United States, remained in garrison and did not challenge the Russians. The Russian military soon controlled the

whole peninsula. After that, events moved very quickly. Crimea held a

referendum in which 96 percent of the 82 percent of the eligible population who

went to the polls voted to join Russia. 42 On March 18, Putin walked into the

Kremlin and announced, to thunderous applause, the reunification of Crimea with

Russia, proclaiming, “In people’s hearts and minds, Crimea has always been an

inseparable part of Russia.” 43

The stealth annexation was masterfully executed and took

the world by surprise. The post—Cold War consensus on European

security was at an end. The leaders of the G-8 countries were scheduled to hold

their annual summit in Sochi in June. But the meeting was canceled, and the

seven other members voted to expel Russia from the group. The luxury hotel

built especially for the G-8 in the picturesque Caucasus Mountains in

Krasnaya Polyana above Sochi stood empty. A year later, at the annual

Munich Security Conference, a stone-faced Sergei Lavrov claimed that the reunification

of Crimea with Russia via a referendum was more legitimate than German

reunification: “Germany’s reunification was conducted without any referendum,

and we actively supported this.” 44 He was greeted with boos.

Putin was now emboldened to mobilize separatist groups

in the Donbas region who resented Kyiv and favored closer ties to Russia, just

as Russia had done in Transnistria, South Ossetia, and Abkhazia. No sooner had

Crimea been annexed than new groups of little green men, a motley

assortment of Soviet Afghan veterans, Russian intelligence agents, mercenaries,

disgruntled pro-Russian Ukrainian citizens who felt neglected by Kyiv,

Cossacks, Russians from Transnistria, and Chechens dispatched by their leader

Ramzan Kadyrov—began to appear in Southeastern Ukraine, particularly Donetsk and Luhansk, and

repeated the Crimean scenario, systematically taking over municipal buildings.

They were called separatists because they supported secession from Ukraine, but

they were in fact insurgents armed by Moscow and led by often feuding Russian

and Ukrainian warlords, yet with one common ambition: to wrest Southeastern

Ukraine from Kyiv’s rule and reunite it with Mother Russia. The Donbas has had

a particularly difficult time coping with the aftermath of the Soviet collapse

and many of its inhabitants still regard themselves as Soviet, as opposed to

Russian or Ukrainian, so they were receptive to these insurgents.

In the ensuing months, Russia poured troops, funding,

ammunition, heavy arms, and other aid across the border to support the

separatists, all the while denying that they were there at all. The Donetsk

People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic were proclaimed early in April

2014. Harking back to Catherine the Great’s eighteenth-century conquests, the

separatists referred to this region north of the Black Sea as Novorossiya. The

first separatist leader and paramilitary organizer in these operations was a

Russian, Colonel Igor Girkin, who went by the nom de guerre Strelkov

(Rifleman). Apart from his previous combat experience in various wars, he

enjoyed participating in historical battlefield reenactments.

Who or what brought MH-17 down?

Unlike in Crimea, however, the Ukrainian Army fought

back this time. The armed forces were weak because much of the Western

assistance given to train and strengthen the military had previously

disappeared into the black hole of corruption. There were also private

paramilitary groups, such as the Azov Battalion, which played a major role in

recapturing territory from the separatists and was eventually incorporated into

the Ukrainian National Guard. In May 2014, in the midst of what was now a

full-fledged war in Southeastern Ukraine, Petro Poroshenko, a confectionery

magnate and former prime minister known as the “chocolate king,” was elected

president. One of his first acts was to go to Brussels and sign the Association

Agreement that Yanukovych had spurned. As the fighting raged in the Donbas,

disaster struck in the air. On July 17, a Malaysia Airlines flight took off

from Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport bound for Kuala Lumpur. It was shot down over

the war zone in Southeastern Ukraine. Many of its 298 passengers were traveling

to a major AIDS conference in Canberra and one of the world’s leading AIDS

researchers was on board. Local residents described pieces of debris and body

parts hurtling out of the sky onto fields covered with sunflowers. Everyone on

board perished. The once bucolic landscape was now a killing field guarded by

heavily armed separatists, who initially prevented any access to the crash

site. Who or what brought MH-17 down? Immediately the tragedy became part of

the information war between Russia and the West. Reconnaissance photography

showed that the plane was shot down by a sophisticated Buk anti-aircraft

missile and the missile had been transported from Russia.45 The Ukrainian

government had recordings of separatist leaders reporting to their Russian

superiors that they had mistakenly shot down a plane they had believed to be a

Ukrainian Antonov military transport, not a commercial airliner.46 Russia

vigorously denied that it had anything to do with the tragedy and blamed the

Ukrainian Army. The majority of victims were from the Netherlands, and the

anger of the Dutch people at constant Russian prevarications was such that

Putin’s elder daughter, Maria, who was living with her Dutch partner in

Amsterdam at the time, had to return to Russia after a Facebook campaign

revealed her address.47 Several inquiries into the cause of the crash have been

hampered by the lack of Russian cooperation. Like so many issues connected to

the Ukraine crisis, the Kremlin continues to deny any involvement, a source of

endless frustration to those seeking a solution to the conflict and restitution

for the lives lost.

The Ukrainians continued to battle the separatists

and, by August 2014, appeared to be in sight of regaining control of the

Donbas. But by late August, regular units of the Russian Army crossed the

border, attacked the Ukrainian forces, and regained separatist territory. In

September, a cease-fire agreement was signed in Minsk by Germany, France,

Russia, and Ukraine, but by December heavy fighting had resumed. Another

cease-fire, Minsk II, was signed in February 2015 and remains the only basis

for a settlement on the table. But even in the three days between its signing

and implementation Russian and separatist forces launched a major assault on a

key Ukrainian transport junction between Donetsk and Luhansk and captured it.

By the terms of the Minsk agreement, each side was required to withdraw its

heavy weapons behind the line of contact, to exchange all prisoners and

hostages, and to allow OSCE officials to monitor the implementation. Foreign

forces and equipment were to be withdrawn, there was to be constitutional

reform in the disputed region, and Ukraine was to regain full sovereignty over

its border with Russia.48 The Minsk II agreement applies only to the war in the

Donbas. It does not mention Crimea. There is a tacit consensus in the West

that, although the West will refuse to recognize Crimea’s annexation, it will

be a very long time—if ever—before Crimea is reunited with Ukraine. Only a

handful of countries—including Cuba, North Korea, and Syria—have recognized its

incorporation into Russia.

Since February 2015, fighting in Ukraine has continued

intermittently, and the OSCE has been constantly thwarted by the separatists in

its attempts to monitor the cease-fire. The Minsk II agreement has barely begun

to be implemented. Russia and Ukraine disagree on the sequencing of

implementation because the agreement itself is vague on that score. Moscow says

Kyiv must introduce far-reaching decentralizing reforms and special status to

the Donbas—which would give the region a virtual veto over Ukraine’s foreign

policy—before Ukraine can regain control over its own border. Kyiv says it will

not begin to introduce constitutional reforms until the Russians have withdrawn

behind the border. Germany, France, Ukraine, and Russia meet regularly at

various levels, and all agree that Minsk II must be fulfilled—but virtually

nothing happens. The United States has had its own bilateral channel with

Russia to discuss Minsk II implementation with Vladislav Surkov, Putin’s close

colleague and author of the “sovereign democracy” concept, who manages the

separatists. Many observers fear that the situation in the Donbas has already

turned into a frozen conflict similar to those in Georgia and Moldova, where

Russia supports separatists who make it impossible for the governments in the

titular state to have full control over their territory. Others question how

“frozen” the conflict is. In July 2017, Kurt Volker, newly appointed Trump

administration special envoy for Ukraine, said after visiting Southeastern

Ukraine, “This is not a frozen conflict, this is a hot war, and it’s an

immediate crisis that we all need to address as quickly as possible.” 49

Meanwhile, the Kremlin has abandoned the idea of

creating a Novorossiya as it was in Catherine’s time. Instead, in July 2017 the

separatists proclaimed a new state of “Malorossiya”

(Little Russia), which would encompass most of Ukraine. Russian officials

disavowed this move, highlighting the opaque nature of Moscow’s control over

the separatists. Some Ukrainians and their supporters in North America have

begun to question whether it really is in Kyiv’s interest to try to regain

control over the impoverished, battle-scarred, unruly Donbas. Since the

beginning of the conflict, so this argument goes, Kyiv is “no longer obliged to

sustain a rust belt that once drained its coffers, endure the region’s corrupt

oligarchs, political elites, and criminal gangs, or appease its pro-Soviet and

pro-Russian population.” 50

Russia has suffered economically from its invasion of

Ukraine. After the annexation of Crimea, the United States imposed sanctions on

individuals close to Putin. But the more serious financial sanctions came after

the MH-17 crash. The new sanctions, imposed by the U.S. and Europe sharply

restricted access for Russian state banks to Western capital markets, a major

source of foreign lending. Under the sanctions, E.U. and U.S. firms were barred

from providing financing for more than thirty days to the country’s key

state-owned banks. This has severely limited the banks’ ability to finance

major projects. Russia’s energy sector was also targeted. Sanctions prohibited

access to certain energy technologies and participation in deep-water Arctic

oil shale development, ending Rosneft’s collaboration in the Arctic with

ExxonMobil. In retaliation, Russia imposed counter-sanctions on European

agricultural imports, and the Kremlin used this to encourage domestic

production of high-end agricultural products. Indeed, at the 2017 Saint

Petersburg International Economic Forum, in what became known as the “cheese

ambush,” a Russian farmer accosted the U.S. ambassador John Tefft and

proudly handed him a large cheese wheel, explaining that he had been able to

produce it because of the ban on competing cheeses from Europe. The ambassador,

though taken by surprise, was a consummate diplomat and explained that he was

from the cheese-producing state of Wisconsin and graciously accepted the gift.

Can the Ukraine Crisis be resolved?

At the 2014 G-20 summit in Brisbane, Australia, Putin

endured hours of criticism from Western leaders about Ukraine and left the

summit early. Yet it was, of course, impossible to isolate him, given Russia’s

relationship with China and other countries. And his calculation-- proven

correct-- was that he could ride out this initial wave of ostracism, knowing

full well that in the end, the West would have to deal with him. The Russian

leader has patience. The West would have to seek him out again, particularly

after Russia launched its air strikes in Syria in September 2015. The 2017

Hamburg G-20 meeting proved him right. He was center stage, sought out by most

leaders, held a two-and-a-half-hour meeting with President Trump, and attended

many other bilateral meetings.

The Ukraine war has been particularly challenging for

the West because Russia repeatedly denies that it is directly involved. Ukraine

is a new type of “hybrid” war, combining cyber warfare, a powerful

disinformation campaign, and the use of highly trained special forces and local

proxy forces. The Russians sought to mask the reality of what was happening by

having “little green men” invade Crimea and the Donbas, claiming that the

Russian soldiers who were observed fighting in the Donbas were “on vacation,” asserting

that trucks going to and from Ukraine were carrying “humanitarian supplies”

instead of weapons and men, accusing Ukraine of shooting down MH-17, and

burying dead Russian soldiers in unmarked graves without informing their

families.51 Ukraine and the West understand that Russia is dissembling and that

there have been as many as tens of thousands of Russian troops in the Donbas,

but the constant barrage of state-run Russian television news tells another

story, not only to Russia’s own population but to those around the world. In

Oliver Stone’s four-hour television interview with Putin, for instance, the

narrative is Putin’s. The audience is told that the separatists are fighting

alone, mobilized by the “coup d’état” in Kyiv, and Putin questions whether

MH-17 was indeed shot down.

In May 2018, the Australian and Dutch governments

published a report detailing the results of their years-long investigations

into the MH-17 downing. Its conclusion was unambiguous: “The Netherlands and

Australia hold Russia responsible for its part in the downing of flight MH-17.”

52 A Dutch police official went further. The investigative team, he said, “has

come to the conclusion that the Buk TELAR by which MH-17 was downed originated

from the 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade from Kursk, in the Russian Federation.

All of the vehicles in the convoy carrying the missile were part of the Russian

armed forces.” 53 The report did not specify who fired the missile, but several

media outlets named a high-level Russian GRU officer tied to the downing.54

Russia continues to deny that it had anything to do with the crash.55 When

Putin was asked at the Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum about

whether a Russian missile had downed the plane, he replied, “Of course not!” 56

There are few signs that Russia is interested in

resolving the Ukraine crisis. Continuing conflict makes it difficult for the

Poroshenko government to function, and the Kremlin wants a weak, divided

Ukraine. Russia and the West have discussed the possibility of deploying U.N.

Peacekeeping troops to the Donbas, but there is no agreement on where these

troops should be stationed or what their remit would be. Western sanctions are

tied to Minsk II implementation, but although Putin would like sanctions lifted,

he apparently is not willing to moderate Russian policy toward Ukraine. Former

secretary of state Rex Tillerson suggested that the U.S. administration should

not be “handcuffed” if Russia and Ukraine work out their differences

bilaterally outside the Minsk II structures. 57 But prospects for such a deal

also appear remote. Putin has indicated that Russia might withdraw to its side

of the border if both the Donetsk and the Luhansk People’s Republics are

granted wide-ranging autonomy, including leverage over foreign policy decisions

made in Kyiv. But Poroshenko does not have the votes in the Rada to pass such

legislation, even if he wanted to. Thus Moscow blames Kyiv for failing to

implement Minsk II, and Kyiv blames Moscow. Meanwhile, all sides realize that

the Crimean issue will not be resolved for a very long time.

Russia has also indicated that a precondition for

Ukraine regaining sovereignty over its territory would be a pledge not to seek

NATO membership and revert to the “non-bloc” status it had

until Yushchenko came to power. However, Poroshenko in July 2017

committed Ukraine to seek NATO membership by 2020. It is not at all clear that

NATO wants Ukraine. The idea that Ukraine should “Finlandize”-- that is, accept

a status similar to that of neutral Finland during the Cold War-- has been

advocated by two U.S. statesmen who often did not agree with each other: the

realist Henry Kissinger and the more ideological Zbigniew Brzezinski. 58

Viktor Pinchuk, prominent Ukrainian oligarch and son-in-law of Leonid

Kuchma, has also argued that Ukraine must give up its aspirations to join the

E.U. and NATO if it wants the war to end. 59 In fact, neither E.U. nor NATO

membership is on offer for Ukraine, nor will they be for the foreseeable

future. But the specter of the United States, Russia, NATO, and the E.U.

agreeing to keep Ukraine neutral is disconcerting. It resurrects the ghosts of

Yalta and the division of Europe into great power spheres of influence, with

limited sovereignty for the countries that lie in the E.U.’s and Russia’s

common neighborhood. It would signal that the post--

Cold War international order, which Russia seeks to undermine, is

indeed over. There is also no guarantee that such an agreement would curb

Russia’s appetite for increasing its influence in the post-Soviet space and

continuing to undermine Ukraine’s ability to function as an independent state.

Nevertheless, it is undeniable that Russia’s stake in

Ukraine is far greater and more compelling than is that of the United States or

many members of the E.U. Ukraine is an existential question for Russia, as

Russia is for Ukraine.

Kyiv is 5,000 miles away from Washington, and until

now Ukraine has not been considered a core interest for the United States.

There is not much ambiguity there. The U.S. and its allies will continue to

support Ukraine’s independence, territorial integrity, and political and

economic development, but they will draw a line at taking actions that would

involve any military conflict with Russia. Berlin is only 750 miles from Kyiv

but will continue to oppose any NATO membership for Ukraine. So despite the tensions

in Russia’s relations with the West that have increased since 2014, Putin knows

there is a limit to how far the West will go to counter Russian actions, as the

reaction to Russia’s seizure of the Kerch Straits showed.

No short-term solution to the Ukraine crisis appears

to be on the horizon. Disillusionment with the lack of reforms and persistence

of corruption has largely soured the people who came to the Maidan in 2013. The

E.U. and the United States continue to deal with the “Ukraine fatigue” that

periodically emerges when Ukrainian leaders make verbal promises to reform but

do not act on them. But Russia’s actions have also served to integrate the

heirs to the Dnieper and Galician Ukraine. Ukrainian national identity has

become more unified in reaction to the Russian invasion and occupation of their

country. The West may be dealing with a frozen conflict that sometimes becomes

hot for some time to come-- but that might be a preferred option in Putin’s

world. Even when Tass recently claimed that

Russia (in spite of by international law, it is occupying Crimea) does not even

as much as occupy ‘any’ Ukrainian territory.

In the end, however, one should not forget that in the

two decades that have seen the rise of Putin’s world, several lessons have

become clear. Isolating Russia and refusing to deal with it, however appealing

that may appear to some, is not an option. The West, therefore, should

encourage a wider dialogue with Russians wherever possible. Above all, it

should be prepared for surprises in dealing with Russia and agile enough to

respond to them, just as Putin’s judo mastery has taught him how to prevail over

an indecisive opponent. In Putin’s world, it is prudent to expect the

unexpected.

As for the elections, following the Russian occupation

of Crimea and military intervention in the east of the country, there was a

widely shared perception that the Ukrainian political system has tilted towards

the Ukrainian-speaking West. That was certainly the thinking behind President

Petro Poroshenko’s decision to emphasize nationalist politics in his

re-election campaign and try to win over the votes of the Ukrainian-speaking

(and supposedly more nationalistic) part of the population in the country’s center

and West.

Recent surveys however show that more than half of Ukrainians actually have a positive

attitude toward Russia. Even back in conflict-ridden 2017, the same number of

Ukrainians named Russia as a military ally as they did the United States.

All this gives us a picture of a rather different

Ukraine to the one Poroshenko was appealing to with his triple patriotic

slogan, “Army! Language! Faith!” There is much less public enthusiasm for

Ukraine’s five-year war with Russia. Servant of the People shows that language

is more important for the intelligentsia, who has overseen the country’s

emancipation from the Russian language for a century than it is for ordinary

people. The characters in Servant of the People, which was filmed for the

domestic market, speak Russian but watch the news in Ukrainian or switch to

Ukrainian in official situations. Finally, Ukraine is more religious than

Russia, and many were pleased to finally get their own independent

Orthodox Church--but ultimately, the final part of Poroshenko’s slogan,

faith, is still less important to most than the economy, medicine, or transport

might have been.

So is all this good news for Russia and Putin? Yes and

no. There were expectations in Russia that Ukrainian public opinion would cool

down after the Maidan revolution and get over the damage inflicted by Russia

when it annexed Crimea and supported separatism in Ukraine’s Donbas region. The

hope was that Ukraine’s silent majority would find their voice at the secret

ballot. The winner would not be a pro-Russian party nor the party of peace

(this is tricky as long as there is no end in sight to the conflict in Donbas)

but the party of geography. These are people who believe that Ukrainian

politics should be built more on the country’s geographical position than on

idealist aspirations. You can do everything possible to be European and as far

from Russia as possible, but those wishes won’t magically transport Ukraine

next door to Austria or Belgium. It will stay just where it is, next to Russia.

That change of mentality will be

welcomed in Russia. Yet, in the longer run, Zelensky could prove a much less

convenient opponent for the Kremlin than Poroshenko is. Putin projects himself

as the leader of global populism, but at home, he increasingly lacks the

popular touch. Surrounded by circumspect technocrats and a close circle of

billionaires, the president is the object of populist derision. Unknown spoiler

candidates are already winning regional elections in Russia, and demand is

building for a people’s candidate at the federal level.

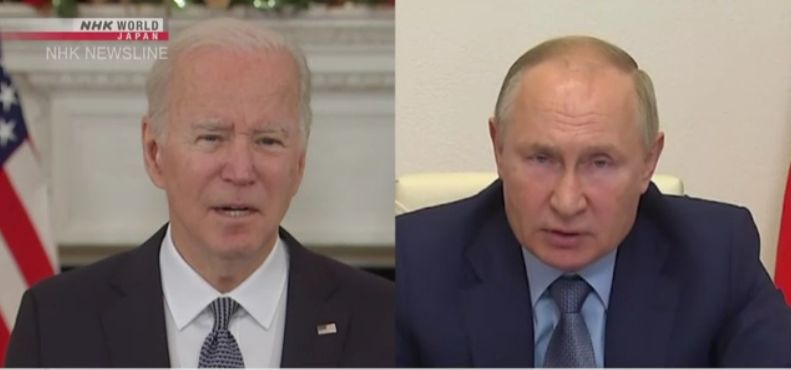

Meanwhile, the White House has announced

President Joe Biden will hold video talks with his Russian counterpart Vladimir

Putin on Tuesday to discuss Ukraine and other issues. Press Secretary Jen Psaki

issued a statement on Saturday saying the leaders will discuss a range of

topics including strategic stability, cyber, and regional issues. She also said

President Biden will underscore US concerns with Russian military activities on

the border with Ukraine and reaffirm American support for the sovereignty of Ukraine.

Update 11 December: Washington's top diplomat for Europe and

Eurasian affairs Karen Donfried will be in Kyiv

and Moscow on 13 and 14 December to meet senior government officials and to

reinforce the United States' commitment to Ukraine's sovereignty, independence,

and territorial integrity. She allegedly will emphasize that we can make

diplomatic progress on ending the conflict in the Donbas through the

implementation of the Minsk agreements in support of the Normandy Format.

The 2015 Minsk

Agreement aimed at halting fighting inside Ukraine, bolstered by the Normandy

Format - a diplomatic push by France and Germany to end the conflict.

1. Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of

Europe: A History of Ukraine, 2017, 98– 100.

2. “From ‘Malorossiya’ with

Love?” Digital Forensic Research Lab, July 18, 2017, https://medium.com/dfrlab/

from-malorossiya-with-love-8765ed30242d.

3. Marvin L. Kalb, Imperial Gamble: Putin, Ukraine,

and the New Cold War (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), 55.

4. Plokhy, The Gates of

Europe, 226– 27.

5. Plokhy, The Gates of

Europe, 253.

6. Paul Robert Magocsi,

A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples, 2014, 574.

7. Mark Kramer, “Why Did Russia Give Away Crimea Sixty

Years Ago?” Cold War International History Project, Wilson Center, March 19,

2014, https:// www.wilsoncenter.org/ publication/ why-did-russia-give-away-crimea-sixty-years-ago.

8. Plokhy, The Gates of

Europe, 298– 99.

9. Roger Highfield, “25 Years After Chernobyl, We

Don’t Know How Many Died,” New Scientist, April 21, 2011, https://

http://www.newscientist.com/article/

dn20403-25-years-after-chernobyl-we-dont-know-how-many-died/.

10. Reuters, “After the Summit; Excerpts from Bush’s

Ukraine Speech: Working ‘for the Good of Both of Us,’” New York Times, August

2, 1991, http:// http://www.nytimes.com/

1991/08/02/world/after-summit-excerpts-bush-s-ukraine-speech-working-for-good-both-us.html?pagewanted=all

11. Serhii Plokhy, The

Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union (New York: Basic Books, 2014),

306– 15.

12. “Annual Address to the Federal Assembly of the

Russian Federation,” President of Russia website, April 25, 2005,

http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/ transcripts/ 22931.

13. Samuel Charap and

Timothy Colton, Everyone Loses: The Ukraine Crisis and the Ruinous Contest for

Post-Soviet Eurasia (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies,

2016), 56.

14. Global Witness, It’s a Gas: Funny Business in the

Turkmen-Ukraine Gas Trade, https://

http://www.globalwitness.org/en/reports/its-gas/.

15. Steven Pifer, The Eagle and the Trident:

US-Ukraine Relations in Turbulent Times (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution

Press, 2017).

16. “Rossisko-Amerikanskii Dialog v Kremle,” Krasnaia Zvezda, January 14,

1994.

17. Strobe Talbott, The Russia Hand: A Memoir of

Presidential Diplomacy (New York: Random House, 2002), 114. See

“Tri Prezidenta Stavit v Kremle Posledniuiu Tochku v Kholodnoi Voini,” Izvestiia,

January 15, 1994.

18. Steven Pifer, The Eagle and the Trident:

U.S.—Ukraine Relations in Turbulent Times, 2017, 70.

19. Celestine Bohlen, “Ukraine Agrees to Allow

Russians to Buy Fleet and Destroy Arsenal,” New York Times, September 4, 1993,

http:// http://www.nytimes.com/ 1993/ 09/ 04/ world/

ukraine-agrees-to-allow-russians-to-buy-fleet-and-destroy-arsenal.html.

20. Pifer, The Eagle and the Trident, 31.

21. Angela E. Stent, “Ukraine’s Fate,” World Policy

Journal 11, no. 3 (Fall 1994): 83– 87.