By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

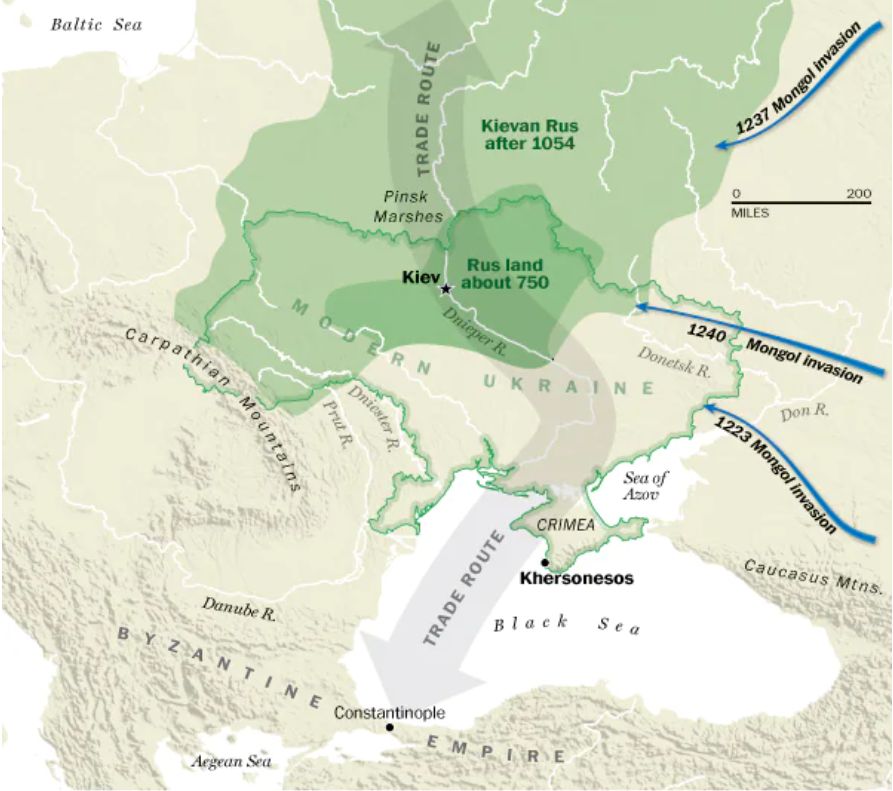

A sketch of how Ukraine became Ukraine over 1,300 years

of history follows. Ukraine's modern borders are outlined in green throughout.

One of 7:

2 of 7 1650 to 1812

The "Rus" -- the people whose name got tacked on to

Russia -- were originally Scandinavian traders and settlers who made their

way from the Baltic Sea through the marshes and forests of Eastern Europe down

toward the fertile riverlands of what's now Ukraine.

Other Viking adventurers journeyed to Constantinople, the great

capital of the Byzantine Empire, to find their fortune -- sometimes as hired muscle.

The first major center of the "Rus" was at Kiev, established

in the 9th century. In 988, Vladimir, a prince of the Kievan Rus, was baptized

by a Byzantine priest in the old Greek colony of Khersonesos

on the Crimean coast. His conversion marked the advent of Orthodox

Christianity among the Rus and remains a moment of great nationalist

symbolism for Russians. Putin invoked this

older Vladimir in a speech last December when justifying his

annexation of Crimea.

Successive Mongol invasions beginning in the 13th century subdued

Kiev's influence, and led eventually to the rise of

other Rus settlements to the north, including Moscow. The Turkic

descendants of the Mongol Golden Horde formed their own Khanate along the

northern rim of the Black Sea.

3 of 7 1650 to 1812

Fast forward a few centuries, and you see how the land that's now

Ukraine lay on the margins of competing empires. It was a region of

permanent contest and shifting borders. The Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth -- which, at its peak, encompassed a vast

swath of Europe -- had dominated much of the land. Still, Ukraine would also

see the incursions of Hungarians, Ottomans, Swedes, bands of Cossacks, and

the armies of successive Russian czars.

In the 17th century, Russia and Poland split much of Ukraine along the

Dnieper River. Russia's advance continued a century later, during the rule of

Catherine the Great, who imagined her domains along the Black Sea

constituted "Novorossiya,"

or "new Russia" -- a term revived by the pro-Russian

separatists in eastern Ukraine. Back then, the Russian court harbored dreams of

collapsing the Ottoman empire and extending Moscow's reach to Istanbul

(formerly Constantinople) and even Jerusalem.

"Believe me, you will acquire immortal fame such as no other

sovereign of Russia ever had," said Grigoriy Potemkin, a prominent adviser

to Catherine the Great, when offering the empress counsel in 1780 on plans to wrest

Crimea away from Ottoman suzerainty. "This glory will open the way to

still further and greater glory."

Meanwhile, the partitions of Poland in the late 18th century led

to the city of Lviv -- once a central

regional hub and a center of Jewish culture in Eastern Europe --

falling under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian empire. It was there in the

mid-19th century where Ukrainian

nationalism began to take hold, rooted in the traditions

and dialects of the region's peasants and the aspirations of intellectuals who

had fled the oppressive rule of Russian rule further to the east.

4 of 7. 1914 to 1918

World War I and the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 triggered more

traumas and upheaval in the areas that now constitute Ukraine. The new

Bolshevik government was desperate to end hostilities with Germany

and its allies and signed a treaty in Brest-Litovsk in

1918, ceding some of Russia's domains to the Central powers and

recognizing the independence of others, including Ukraine.

The treaty's terms were nullified by Germany's defeat later in the

year, but the genie of Ukrainian nationalism was out of the bottle.

Independence movements of various stripes sprung up in cities like Lviv, Kyiv,

and Kharkiv but were eventually swept away amid Russia's broader struggle for

power.

5 of 7. 1919 to 1922

At the end of World War I, a revived Poland reclaimed Lviv and a chunk

of western Ukraine. The country was one of the critical battlegrounds of the

Russian Civil War, pitting Bolshevik forces against an array of armies,

led by loyalists to the old czarist regime and other political

opportunists. After many bloodsheds -- and other battles with Poland -- the

Bolsheviks emerged

triumphantly and officially declared the Ukrainian

Socialist Soviet Republic in 1922.

The years that followed would be even more traumatic: in the late 1920s

and early 1930s, Ukraine suffered heavily under the rule of Soviet despot Josef

Stalin. A vast segment of Ukraine's rural population was displaced and

dispossessed by Stalin's aggressive collectivization policies. Artificial famine in 1932-3 led to the

deaths of some three million people.

Russian speakers from elsewhere immigrated to Ukraine's

hollowed-out towns and cities to make up the numbers, leaving a demographic

footprint that defines Ukraine's divisive politics to this day.

6 0f 7. 1945 to 1954

World War II ravaged Ukraine. Hitler and other Nazi strategists

imagined it could become the

breadbasket of their more enormous German empire.

Instead, it was a hideous, bloody warzone shaped by epic, grinding battles and

various massacres of civilian populations. Some Ukrainian nationalists

cooperated for a time with Nazi authorities, seeing the invasion as a means to achieve their independence. This was

particularly the case in western Ukraine, which until the end of World War II,

had no experience of Soviet rule.

The "fascism" of these Ukrainian

guerrillas is still a source of controversy now. Some militant elements in the

anti-Yanukovych protest movement actively embraced the legacy of Nazi-affiliated

war heroes. Meanwhile, the Kremlin's propaganda organs used

this history to label the new government in Kyiv as one riding

on a wave of "neo-Nazism."

After World War II, the Soviet Union claimed Lviv and its surrounding

lands in Ukraine's west. The Crimean peninsula, whose population was majority

Russian (after the mass deportation of Crimea's Tatars), was formally ceded from

Russia to the Ukrainian socialist republic in 1954 by Soviet leader Nikita

Khruschev.

7 of 7. After the fall of the U.S.S.R.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine emerged as one many new

independent post-Soviet states in 1991. Its politics were riven by regional

divides between the country's west and the Russian-leaning east. Russia

chose to maintain a naval base in Sevastopol, the main port city in Crimea's

southern tip.

For updates click hompage here