By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

The Situation Ukraine Is Facing This

Winter

Since mid-October,

Russia has repeatedly targeted civilian air and missile strikes against civilian

targets. Over the past

several weeks, infrastructure across Ukraine has been taking out the Ukrainian

economy's vital organs. The man newly in charge of Russian forces in

Ukraine—General Sergei Surovikin, so ruthless that

even his colleagues call him “General Armageddon”—has shown no signs of

relenting. Russia has successfully attacked 40 percent of Ukraine’s power grids

with missiles and Iranian drones. It has bombed energy facilities, including

hydroelectric dams, leaving more than one million

Ukrainians without

electricity. In Kyiv, 80 percent of residents are without water, according to

the city’s mayor. Economists project that Kyiv’s economy will

shrink by at least 35 percent in 2022, and the United Nations

estimates that nine of ten Ukrainians could be impoverished by Christmas.

Men carry boxes with humanitarian aid in the recently

retaken town of Izium, Ukraine.

For the West, the

recent attacks should invite a sense of déjà vu. In 1948, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin blockaded the western sector of Berlin,

controlled by the United States and its allies, as part of his plan to ultimately

dominate a unified Germany. The Soviets cut off all access to the city by rail,

canal, and road, inflicting tremendous hardship on West Berlin. But the United

States and the United Kingdom quickly responded to the Berlin blockade with

what came to be known as the Berlin airlift, flying in food, coal, and other

necessities to the besieged city and successfully foiling the Soviets’ cruel

plan. By May 1949, Stalin had lifted the blockade, and the Federal Republic of

Germany was founded the same month. The West won early in the Cold War, thanks

to its unwavering stance.

Ukrainians cross an improvised path under a destroyed

bridge

Today, as Russian

President Vladimir Putin seeks to subjugate Ukraine, the West

is facing a new Berlin blockade moment. It should channel the same

determination to prevent Putin from destroying Ukraine that it mustered with

the Berlin airlift. The United States and Europe must act now to ensure that

Ukraine survives the winter by adopting various measures, including additional financial

assistance, equipment to restore power and heat, and air defense systems to

protect Ukraine’s infrastructure from the continued onslaught of Russian

missile strikes. Sufficient aid to Ukraine will ensure that the country can

emerge from a daunting winter battered but primed for recovery, just as West

Berlin did in 1949.

Send Lawyers, Guns, And Money

The money the West sends

to Ukraine is just as important as the weapons systems being delivered. Absent

the injection of $8.5 billion from Washington, Ukraine would have gone bankrupt

overnight. Thanks in part to such aid, the country’s banking system, railways,

and hospitals continue to function. Eight months into the war, Kyiv promptly paid state salaries and pensions. But

it confronts a budget deficit of $5 billion to $6 billion each month, forcing

Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance to scramble to ensure that state services are not

threatened.

Russian President Vladimir Putin with then-PM Dmitry

Medvedev and Sergei Surovikin in 2017

The EU committed to

sending $9 billion in loans in May 2022 but is

dragging its heels on sending a final tranche of $3 billion. It will likely

only arrive next year. The public pledges are there, but the willpower has been

wanting. At a G7 meeting in early November, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock stated, “We

will not allow the brutality of this war to lead to masses of elderly people,

children, young people, and families dying in the coming winter months.” In

October, Christian Lindner, Germany’s finance minister and a budget hawk,

denied that Berlin is slow-rolling funding.

Withholding or

slowing the transfer of funds heightens the danger that hyperinflation in

Ukraine could ignite. A shortage of funds has prompted the central bank to

increase the money supply by purchasing billions in government bonds, thereby

eroding the value of the country’s currency, the hryvnia. In September,

Ukraine’s inflation rate rose to almost 25 percent. Hyperinflation would make

it even harder for the Ukrainian state to stay afloat, let alone successfully

prosecute the war.

The EU is

contemplating a further $18 billion transfer for 2023, but whether it will come

through is an open question. With Germany in particular, there has been a

marked difference between what it promises publicly and what it delivers. The

EU’s pledged support plus a potential new $10 billion infusion of funds for the

next two years from the International Monetary Fund would help to remedy Kyiv’s

immediate financing gap, which is several billion a month. Since the conflict

began in February, the U.S. Congress and the Biden

administration have regularly dispatched vital defense and financial

packages.

Alas,

as Ukraine enters the winter, already without power and in the dark,

support in the United States is starting to buckle. In September, almost all

House Republicans voted against a funding bill that contained $12 billion for

Ukraine. Kevin McCarthy, the leader of the Republican minority in the House,

recently warned that should the GOP win control of the House, it will refuse to

write Ukraine a “blank check.” At a campaign rally in Sioux City, Iowa, on

November 3, Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Georgia Republican who is

a frontrunner for a leadership position in a new Congress, declared: “Under Republicans,

not another penny will go to Ukraine. Our country comes first.” Indeed, a

new Wall Street Journal poll indicates that while most Americans continue to back aid

to Ukraine, the number of Republicans who believe America is granting excessive

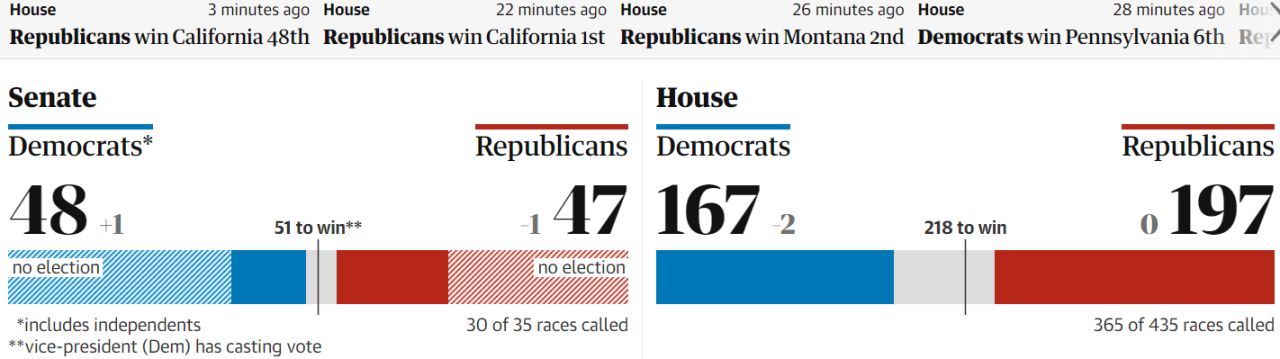

support has rocketed to 48 percent. And with the current mid-term elections,

this has become even worse:

Maintaining US

subventions will be difficult, considering the Republicans win control of

the House of Representatives. Yet compared with the massive budget outlays for

the U.S. Defense Department, the aid to Ukraine is not only modest but

something of a bargain. For the fiscal year 2022, Congress appropriated $728

billion for the Pentagon. Meanwhile, it has committed over $18 billion in

security assistance to Ukraine since the war began in February. The result of

that spending is that Russia has been significantly weakened. Its ignominious

defeats on the battlefield have rendered hollow its pretensions to great-power

status, dramatically magnifying the relative military power of the United

States almost overnight.

Rep. Victoria Spartz surveys

damage to buildings in Bucha, Ukraine, on April 14, 2022.

Some Republicans,

such as Victoria Spartz, the Ukrainian-born Indiana

congresswoman, have raised

the specter of corruption in Kyiv. There can be no doubt that the Ukrainian

government has a long history of speculation, but in the case of budgetary

support during the war, it has worked hard to be a good citizen.

This year, for example, Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance has opened its books to

the financial consulting company Deloitte. For months, its auditors have been

embedded in the ministry and oversee funds as they are transferred, ensuring

they are spent as intended and not stolen. In addition, most U.S. funds are

being provided on a reimbursement basis, minimizing the risk of fraud and

embezzlement. Given the conspicuous lack of evidence of fraud, arguments

against sending aid citing Ukrainian corruption are nothing more than

convenient excuses to do nothing and let Moscow triumph.

Leave A Light On

Money is scarcely the

only problem confronting Kyiv. Moscow’s attacks on Ukraine’s energy

infrastructure have led to blackouts. The government is requesting that its

citizens voluntarily turn off their electricity and mandating rolling

blackouts, thereby reducing the demand for power stations so they can be

repaired appropriately. By and large, the public is complying. When Russia

launched a barrage of missile strikes on October 10 in retaliation for the

bombing of the Kerch Strait Bridge, which connects the Crimean peninsula to

Russia, Kyiv residents rushed to gas stations to fill their tanks, but there

was no mass panic.

The Kremlin hopes

that through its bombing campaign, it can weaponize refugees, provoking a fresh

exodus to Poland and elsewhere this winter. This would be a recipe for stirring

up political turmoil and emboldening far-right parties, many of whom are

sympathetic to Putin. Already German cities, for example, are overstretched in

absorbing an influx of over one million refugees from Ukraine. The refugee

crisis is the biggest Europe has witnessed since the end of World War II. Right

now, however, Ukrainians remain defiant: Oksana Nechyporenko,

a prominent civil society leader, told us that no one is panicking but that her

friends with children are searching for safer places in Ukraine to live during

the winter. Nechyporenko lives on the 14th floor of

an apartment building in Kyiv, and the periodic blackouts mean that she must do

the exhausting 20-minute climb up the stairs to her door each time she returns.

Since the missile strikes began on October 10, schools have

reverted to teaching remotely, a particularly unfortunate development given

that 3,000 of Ukraine’s schools could reopen on September 1 after being closed

since February.

“Putin doesn’t have

to use nukes to cause a catastrophe,” said Victoria Voytsitska, the former chair of the Ukrainian

Parliament’s energy committee, during an October interview with us in

Washington, D.C. “It’s impossible to protect Ukraine’s heating system.” Voytsitska, like Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky,

has been urging the West to send air defense systems to Ukraine as soon as

possible. The damage Russia has inflicted since mid-October has been extensive.

Half of the population in Chernihiv, a city in Ukraine’s north, lacks water

because it requires electricity to pump and deliver it.

In Zelensky’s

hometown of Kryvyi Rih in central Ukraine, Moscow has repeatedly hit a dam,

causing residents to evacuate their homes in case the area floods. In

Zaporizhzhia, in the southeast, half of the city doesn’t have heat. Voytsitska urged donors to invest in “warming shelters,”

safe public rooms in cities and towns where residents can stay 24 hours a day

when temperatures plunge, and there is no heat or power. She’s also worried

about what might happen if Russian missiles hit hospitals: patients could be

left to freeze to death. Voytsitska’s worries are not

theoretical. In March, for example, 300 Ukrainians froze to death in Chernihiv.

In the short term,

the West can help Ukraine repair its electrical grid. Already, Lithuania is

sending technical parts—mostly transformers and electrical cables— to repair

power generation stations. Many urgently needed parts require a long wait, so

Western countries can prod the companies that manufacture them, such as

Siemens, to put Kyiv at the head of the line. But even if some of Ukraine’s

heating systems can be repaired, Moscow will attack again and again. According

to the investigative news outlet Bellingcat, a secret military unit composed of 33 engineers

based in Moscow is carefully directing the Kremlin’s targeting of Ukraine’s

civilian infrastructure.

Ultimately, sending

air defense systems is the best way to protect Ukraine’s energy systems and its

civilian population. Five months ago, Germany pledged to send four systems but

has only delivered one: an IRIS-T air defense system, which provides

medium-range, high-altitude protection for small cities. The rest are expected

to be delivered in the new year. Air defense systems are complex, expensive,

and in high demand, but Ukraine is in dire need of them. Kyiv has officially

asked Israel for a number of these systems. It is high time for Israel to end

its neutral posture on the war and start supplying Ukraine with the weapons it

needs, including Israel’s vaunted Iron Dome and technicians to train Ukrainians

on how to use them. For its part, the United States is trying to speed delivery

of two advanced surface-to-air missile systems, with six more coming

later.

As Putin seeks to

pound it into submission, Ukraine continues to advance on the battlefield, and

its troops’ morale remains high. But for the country to survive the winter, the

butter will be as important as guns. A spell of warm weather and abundant

imports mean that European gas storage facilities are over 90 percent full,

ensuring that fuel prices in Europe have also plummeted. So far, Putin’s

attempts to bully Europe on the energy front are failing as miserably as his

military adventure. But Putin continues to hope that the Western public will

tire of the conflict and push their governments to concede to his demands.

However, for Washington and its allies, failure in Ukraine would mean confronting him again on another European battlefield.

The faster the West aids Ukraine, the more quickly

it can stymie Putin’s ambitions.

Kherson

On a more positive

word today, Ukraine pushes Russia out of Kherson, the most significant

liberation yet. But even though Ukrainian troops are still raring to

advance in the frigid temperatures, intelligence officials remain wary of the

situation in Kherson, which is believed to be heavily mined by departing

Russian troops, a tactic that dates back to the Second World War and one that

has been used heavily in the full-scale invasion of Ukraine to sow death and

dismemberment for Ukrainians returning. The Ukrainian military official

said troops would have to wait to seize the city until it was relatively clear

of mines and booby traps.

More U.S. help may

also have to wait. On Tuesday, Colin Kahl, the Pentagon’s policy chief, told

reporters that arming Ukraine had begun to take a toll on Western ammunition

stockpiles. There’s also been no signal from the Biden administration that the

longer-range U.S. Army Tactical Missile System, which can be fired from

truck-mounted HIMARS cannons, is coming any time soon, even as Congress could

push for more than $50 billion in aid to Ukraine during the lame duck.

Still, with more of

the country back in Ukrainian hands, officials in Kyiv today were breathing

easier about haggling with Western officials over military aid.

Kherson city was the

only regional capital Russia had captured since its invasion in February. The

abandonment of such a strategic prize would be a significant

setback for Moscow's

“special military operation” in Ukraine.

For updates click hompage here