By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

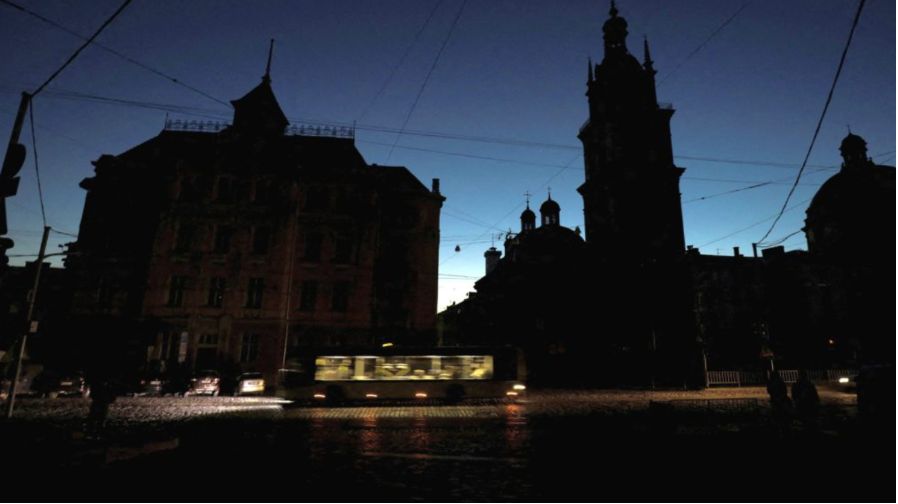

What Russian Airstrikes Will Result In

On October 10-11,

Russia escalated its war against Ukraine with an enormous wave of airstrikes against

Ukrainian civilian infrastructure since the invasion began almost eight months

earlier. In a 10 October statement, Secretary-General António Guterres called the air

assaults “another unacceptable escalation of the war.”

The Kremlin has

telegraphed that it wanted to slow Ukraine’s battlefield advances with strikes

targeting infrastructure and civilians. Russian troops’ cruel logic, experts

said, is that if they can’t beat Ukrainian soldiers on the battlefield, they

will try to harm their wives and children at home. And Putin also has to play

for time, spreading out Ukrainian defenses, with a purported 300,000 mobilized

Russian reserves not set to be ready for weeks.

Beginning in

early October, facing huge territorial losses and other reversals in

Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin reached for a military strategy in

which Russia should have a decisive advantage: airpower. In the most widespread

such campaign, he ordered a blistering series of missile attacks against a

dozen cities and electrical infrastructure across the country. Ukrainians were

forced into basements and bomb shelters, and some 30 percent of the country’s

power generation capacity was knocked out, causing rolling blackouts that

affected homes, hospitals, and even the basic functioning of the economy.

Recently, Russia has sent waves of drones to attack residential buildings and

offices in Kyiv and other cities. In effect, Putin reminded the Ukrainian

government of his ability to attack its main population centers.

The threat that

Ukraine, having scrapped Soviet-era bombers long ago, having no long-range

rockets able to hit Russian cities, and having only a tiny number on

the ground, the goal, it seems, is to punish civilians, wearing them down

in the hope of convincing their leaders to sue for peace.

But as suggested before, it is a strategy doomed to

failure. As in earlier phases of the war, Russia’s supposed air

superiority has done little to shift the overall momentum on the ground.

Despite the significant damage they have caused, Putin’s airstrikes have failed

to hinder Ukrainian advances in the east. And when they have reached civilian targets,

they have only served to strengthen Ukrainian resolve.

The paradoxical

outcome of Russia’s bombing campaigns suggests a more critical insight into

airpower in contemporary warfare. For decades, bombing civilian areas—as ugly

and immoral as it gets in war—has been one of the most common strategies states

have used to undermine the target population’s morale and induce the target

government to surrender. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, especially his

recent escalation, has been no different. But as dozens of conflicts over

the past century have demonstrated, using airpower against civilian targets is

almost always doomed to failure. And as target countries like Ukraine obtain

more advanced land-based munitions, the flaws of the airpower strategy have only

become more apparent.

The Myth Of Shattered Morale

Modern states have

often sought to punish the civilian populations of their adversaries.

Generally, they have done so as a cheap and easy way to compel enemy

governments to make concessions, retreat, or even surrender outright. The most

common air strategy is attacking civilians, either directly by bombing

residential areas or indirectly by damaging the economic infrastructure

necessary for food distribution, homes heating homes, and the electrical

powering of the civilian economy.

The idea started in World War I, when German leaders,

desperate to knock the United Kingdom out of the war, launched waves of

zeppelins—huge maneuverable balloons loaded with bombs—to attack London and

other British cities. Later they added Gotha aerial bombers, killing

many hundreds but producing no results until finally calling off the

punishment campaign in 1917. Other strategic-bombing advocates, like Italian

General Giulio Douhet, wrote highly influential books

claiming that huge air attacks on the enemy’s cities would cause civilians to

rise and demand that their government surrender, thus producing victory without

the need for messy ground battles. Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United

States rapidly expanded their air forces in the 1920s and 1930s, basing their

doctrines on the premise that direct or indirect attacks on civilians would be

the key to winning modern wars.

These “get tough” strategies

by governments have often been welcomed by their public because they can

produce dramatic, immediate tactical results at a little military cost to one’s

side and extract what is perceived as a measure of revenge for the rival's

actions. Occasionally, strategic airpower had had notable results on the

battlefield, as when the United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force suppressed tribal

rebellions in Iraq in the 1920s and when German planes helped General Francisco

Franco’s Nationalist army capture territory in the Spanish Civil War. However,

often overlooked in these cases was that changes in the military balance on the

ground, rather than punishment of civilians, played a decisive role.

As many other

conflicts have shown, the gains of punishment strategies tend to be

short-lived. Consider what happened when German bombers blasted London and

other British cities in 1940–41, killing more than 50,000 people. Like

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky today, British Prime Minister Winston

Churchill refused to hide in bomb shelters. He would walk through the rubble,

leading through demonstrative action and rallying the whole of society to make

the sacrifices necessary for ultimate victory. Instead of shattering morale,

the Blitz motivated the British to launch—with their American and Soviet

allies—the counterattack that ultimately conquered Nazi Germany.

Indeed, inflicting

punishment on civilian areas is immoral and is singularly unproductive as a

strategy for putting pressure on an adversary. Whether the punishment is meted

out massively or lightly, quickly or slowly, whether it is combined with

diplomatic proposals or not, the historical record shows that harming civilians

is also unlikely to compel rival states to surrender or to cut deals that

effectively abandon territory that is important to the viability of the state

or national identity.

Nor is there any case

in which a bombing campaign has caused the targeted population to revolt

against their government. For example, in several major wars in the second half

of the twentieth century, Washington sought to foment popular uprisings against

enemy regimes by attacking civilian infrastructure. Thus, during the Korean

War, the United States destroyed 90 percent of power generation in North Korea;

in the Vietnam War, it knocked out nearly as much power in North Vietnam; and

in the Gulf War, American air attacks disrupted 90 percent of power generation

in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. But in none of these cases did the population rise

up. Strikingly, the United States did not bother attacking Iraq’s electric

power grid or civilians during its 2003 invasion. Concentrating on effective

military strategy, it could easily defeat Iraq’s army and topple the Saddam

dictatorship in six weeks.

In World War II,

of course, the effects of the Allied bombardment of Germany and Japan were much

more extreme. Cities were firebombed and destroyed by U.S. and British forces;

conventional munitions killed more than 300,000 German civilians and 700,000

Japanese civilians—and more than 20 percent of each country’s population was

homeless. Yet even then, there was no public pressure on either regime to

surrender. Suppose modern nation-states in fights for the control of their

homeland can withstand that. In that case, there is little reason to think that

Russia’s relatively less punishing bombardment of civilians in Ukraine will

cause Ukrainians or their leaders to give in.

Hammer Requires Anvil

By contrast, airpower

has proved effective in achieving military objectives rather than punishing

civilians. In war after war, theater airpower—smashing enemy ground forces and

weakening them to the point where one’s ground forces can dominate a zone of

conflict—can provide a powerful tool of coercion combined with adequate land

power. In 1972, the United States compelled North Vietnam to cease conventional

aggression by coordinating its massive Linebacker bombing campaign with South

Vietnamese army forces. In 1991, the United States successfully made Saddam withdraw from Kuwait by combining the first

modern precision air campaign with a coalition of ground forces. And the

absence of theater airpower can seal the fate of a friendly army, as the United

States discovered when Congress blocked the use of U.S. airpower in Vietnam in 1974, and Saigon fell the following

year. The lesson was repeated in Afghanistan, with the U.S. withdrawal of

theater airpower before the collapse of the Afghan army in the summer of 2021.

A Ukrainian flag on a street of the recently liberated

village of Vysokopillya

The combined use of

theater airpower and friendly ground forces has a clear logic. Once wars begin

in earnest, achieving victory becomes paramount. In war, successful leaders

soon discover—sometimes after exhausting cheaper but less effective

strategies—denial is the key to successful coercion. Successful leaders realize

there is no realistic option other than directly thwarting the enemy’s ability

to take or hold territory. In other words, the coercing state succeeds to the

extent that it can prevent its opponent from achieving its military objectives.

In actual warfare,

denial works best via a strategy in which the combined force of air power and

ground power puts the enemy in a military Catch-22. Suppose the enemy

concentrates its ground forces in large numbers to form thick and overlapping

fields of fire to withstand a ground assault best. Those forces will become

vulnerable to the air, and the airpower hammer can smash them to bits. But

suppose the enemy disperses its ground forces across a wide area to make

effective airstrikes more complex. In that case, it risks leaving them thinly

scattered and exposed to easy defeat on the ground, allowing friendly ground

forces to overwhelm isolated enemy units, easily break through weak enemy

lines, and encircle vast portions of the enemy forces.

From its previous

wars, Russia should have understood the

need to combine air and ground power. Consider its supposed successes in

punishing civilians in Chechnya during the 1990s or in Aleppo during the Syrian

civil war. Although Russian military forces indeed extracted a heavy price from

civilian populations in both cases, what ultimately mattered was the balance of

forces on the ground. In Chechnya, Russia blasted civilians in Grozny in 1994. Still, its ground forces were soon

defeated by the rebels, and the Russian military successfully conquered the

republic by invading with a much larger ground army in 1999. In Aleppo, the

forces of Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad and Hezbollah ultimately made the

difference, taking rapid control of areas bombed by Russia. Take away these

well-equipped ground forces, and Russia’s air campaigns would almost certainly

have failed.

From The Ground Up

Much has been made in

recent years of advances in precision weaponry, ostensibly strengthening the

hand of airpower. Yet today’s precision

weapons have not proved any more effective in coercing enemies by destroying

political and economic targets in civilian areas since it has long been

possible to destroy such targets with large numbers of “dumb” bombs. Nor have

precision weapons made strategies targeting the enemy’s leadership any more

effective. Such efforts have repeatedly failed against various enemies,

including Muammar al-Qaddafi in 1986; Saddam Hussein in 1991, 1998, and 2003

(ground forces finally captured him); and Hezbollah leaders in 2006.

Moreover, nothing

motivates an enemy’s civilian base more than killing its leader. In April 1996,

Russia used air-to-ground missiles to assassinate the Chechen leader Dzhokhar Dudayev, only to

see a more energetic leader take over, kick Russia’s ground forces out of the republic,

and win control when Russia invaded with massive ground forces three years

later. There are exceptions to this pattern, but they only prove the rule:

aerial targeting of al Qaeda leaders in Pakistan

from 2001 to 2010 succeeded in weakening the group, precisely because it had so

little indigenous support in Pakistan.

The true innovation

of precision airpower has been to enhance the value of the hammer-and-anvil

strategy. Today’s precision weapons allow airpower to destroy

massed enemy ground troops more efficiently and attack other smaller but

essential battlefield targets. Until the advent of these weapons, airpower

could rarely destroy tanks, trucks, command posts, or bridges used to supply

fielded forces, even with thousands of bombs aimed at these tiny targets. Now,

satellites, advanced sensors, and various manned and unmanned bombing platforms

can reliably locate concentrated enemy forces for precision strikes

to destroy.

This precision

revolution has been more evident than in Ukraine’s military forces. Even

before the arrival of advanced precision weapons from the West in the early

summer, Ukrainian forces had been greatly strengthened by the fighting resolve

that Russia’s failed invasion strategy had provoked. Since then, Ukrainian

troops have been able to use two primary forces and an encirclement

maneuver splendidly to Kyiv’s advantage—not only in defending against Russia’s

initial incursion but also in rolling back Russian forces, even in areas of the

east that were far better defended. These tactics have been especially

effective against Russia’s most dug-in, best defensively fortified ground

forces in eastern zones of the country. Ukraine’s triumphs in these situations

have been made possible not by tactical airpower but by advanced ground-based

weaponry, such as the HIMARS missile system. It is not a stretch to consider

each HIMARS missile battery—the United States has provided Ukraine with 16 of

them, with another 18 on the way—as having the air-to-ground combat power and

effectiveness of several F-16 aircraft. With the flexibility and range to

coordinate with Ukrainian ground forces, they can be used against Russian

forces in a given area, wherever they may be.

Just as important,

Russia has made clear through its battlefield performance that it has hardly

begun to move into the precision age. The world has witnessed how poorly a great

power with a huge but largely “dumb

bomb” military may fare against a much smaller state with access

to precision-age weapons. The Russian military has been losing territory

steadily for many months—in March and April. It May near Kyiv and the border

with Belarus, and since the early summer in the territories, it had newly

seized in the east. There is no obvious reason to think that the Russian

military’s pre–February 2022 positions in the east and Crimea are not

ultimately vulnerable as well.

Losing Ukraine Or Losing Russia?

Given the failure

of Putin’s campaign of civilian

punishment and the growing effectiveness of Ukraine’s HIMARS-assisted

ground offensive, many commentators have begun to ask how the war might

end. History shows that when an opponent is persuaded that specific

territorial objectives cannot be achieved, it is likely to concede that

territory, either tacitly or formally, rather than suffer further pointless

losses. But this form of coercion—getting an opponent to recognize that

prolonging a war is futile—is rarely cheap or easy. Even successful coercion

usually takes nearly as long and costs almost as much as fighting a war to a

finish. This lesson applies readily to the war in Ukraine today.

Given current

military realities, those calling for the United States and its allies to

persuade Ukraine to accept a deal in the east are asking the

West to bail out Russia. This is unrealistic for two reasons. First, Ukraine

will not and should not agree. Its forces have the momentum and have every

reason to expect more territorial gains, and it would be foolish to force them

to abandon a winning hand. Second, Russia might accept a deal soon but could

easily violate it months or years later. In short, any deal in eastern Ukraine

is unlikely to be credible unless powerful reinforcing mechanisms can back it

up. These mechanisms would need to include agreements to respect international

borders with the presence of third-party oversight, as well as military forces.

They would likely be necessary to stabilize any end to the war, negotiated or

not.

In the meantime, the

United States and NATO are right to reinforce support and provide additional

air defenses for Ukraine. These steps can mitigate some of the harm to

civilians by Russia’s attacks and demonstrate that attacking urban centers

only hardens the resolve of the West and Ukraine. Ultimately, an end to the war

while the current regime remains in power in Russia would likely require

establishing a hard militarized border to keep Russia from potential conquests

in Ukraine and other parts of eastern Europe. As with the Iron Curtain during

the Cold War, such a fortified boundary would prevent advances in both

directions. It would also deter any conventional offensive by either side by

denying Russia and the West the prospect of rapid territorial incursions.

But as Putin has made

clear with his escalating nuclear rhetoric, the

conflict potentially involves more than

conventional weapons positions in eastern Ukraine. Still, he could

risk losing large parts of Russia by going nuclear. To paraphrase the German

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, this would be committing suicide for fear of

death.

Indeed, no matter how

lethal its bombs are against civilians, Russia cannot reverse its strategic

failures in Ukraine, which are already playing out. Once Putin lost the gamble

that Russia’s military had the wherewithal to defeat and occupy all of Ukraine

in the February–March blitzkrieg campaign. Once Ukraine and the West responded

by mobilizing a powerful counterbalancing coalition to defend the country,

Russia’s options narrowed almost immediately. Since April, many in the West—and

Putin and others in Russia—have been watching the inevitable aftermath of the

initial miscalculations that led to that massive failure.

Putin can punish

Ukrainians, as his air campaign has shown. But lacking an effective

hammer-and-anvil strategy of his own, he is only losing faster. The only

question is whether he will accept a new iron curtain separating Russia from

Europe or continue fighting pointlessly to the finish and risk losing parts of

Russia.

As for today, Western

analysts gave an unambiguous interpretation of Russian general Surovikin's statements about "difficult

decisions" regarding Kherson. They believe it means preparing for a

retreat from the right bank of the Dnieper. While British intelligence suggests

that the withdrawal will be carried out with the help of a barge bridge and

pontoon crossings. And The American Institute for the Study of War reports

that Surovikin's statements "are likely attempts

to set information conditions for a full Russian retreat across the Dnipro

River, which would cede Kherson City and another significant territory in

Kherson Oblast to advancing Ukrainian troops.

For updates click hompage here