By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

How Ukraine Can Take Back All Its

Territory

In recent days, the Russian

occupation authorities have likely ordered preparation for the evacuation of

some civilians from Kherson. They likely anticipate combat extending to the

city of Kherson itself. For too long, however, the global democratic

coalition supporting Kyiv has focused on what it should not do in the invasion

of Ukraine. Its main aims include not letting Ukraine lose and not letting

Russian President Vladimir Putin win—but also not allowing the war to escalate

to a point where Russia attacks a NATO country or

conducts a nuclear strike. These, however, are fewer goals than vague

intentions, reflecting the West's deep confusion about how the conflict should

end. More than seven months into the war, the United States and Europe still

lack a positive vision for Ukraine's future.

The

West believes Kyiv's fight is and wants Ukraine to succeed. But it is not

sure yet whether Ukraine is strong enough to retake all its territory. Many

Western leaders still believe that the Russian military is too large to be

defeated. This thinking has led the members of the pro-Ukrainian coalition to

define only their interim strategic military goals. They have not plotted out

the political consequences of a complete

Russian military collapse.

It is time to start: Ukraine can win big. The country has repeatedly

proved that it is capable of routing Russia. It first prevented Russia

from seizing Kyiv, Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Sumy, and the Black Sea coastline. It

succeeded again by halting Russia's concentrated offensive in the Donbas, the

eastern Ukrainian region comprising Donetsk and Luhansk Provinces, part of

which Russia has occupied since 2014. Most recently, Ukraine retook Kharkiv

Province in less than a week, broke through Russia's defensive lines in the south,

and began liberating parts of the east.

The West best joins

Kyiv in aiming for an unequivocal Ukrainian victory. It should recognize that

Ukraine's military is not just more motivated than Russia's but also better led

and better trained. To win, Ukraine doesn't need a miracle; it just needs the

West to increase its supply of sophisticated weaponry. Ukrainian forces can

then move deeper and faster into enemy lines and overrun more of Russia's

disorganized troops. Putin may respond by calling up additional soldiers,

but poorly motivated forces can only delay a well-equipped Ukraine's eventual

triumph. Putin will then be out of conventional tools

to forestall losing.

Somehow, the White

House is afraid to plan, drawing down military equipment more slowly than either U.S. stocks or the budget requires

(much to the ire of both Senate and House Armed Services Committee Democrats

and Republicans) and sitting on more than $2 billion in drawdown authority until it expired.

Hence outside

analysts worry that before facing defeat, Putin would try to inflict massive

civilian casualties on Ukraine, seeking to coerce the Ukrainian government into

making concessions or even surrendering. He might do so, Western analysts fear,

by continuously targeting densely populated areas in Ukrainian cities with

long-range missiles—as he has done this week—or through carpet-bombing raids.

But Putin lacks the resources to truly level Ukrainian cities. Russia's remaining

inventory of conventional missiles and bombs is large enough to cause

substantial damage, but it is not big enough to destroy swaths of Ukraine.

And Ukraine fight on even when Russia reduces cities to rubble. Putin

destroyed Mariupol, ruined large parts of Kharkiv, and launched thousands of

strikes on other cities and regions. The damage made Ukrainians more committed

to victory and reduced chances for negotiated settlements.

Many Westerners also

fear that Putin might act on his threats to

use nuclear weapons. But the West can intimidate Putin in ways

that will deter him from seriously contemplating such an attack, and a nuclear

strike might turn all global powers, not just the United States and Europe,

against him. It is ultimately unlikely that Putin will go nuclear. But if he

does, the West must ensure his plan backfires.

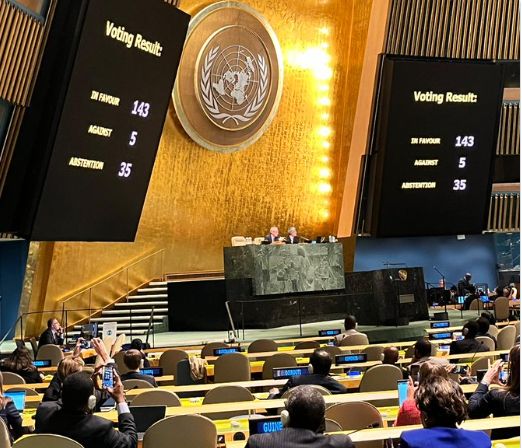

The United Nations

General Assembly has voted overwhelmingly to condemn Russia's attempts

to annex four regions of Ukraine:

As Ukraine's

counteroffensive advances against an increasingly cornered Putin, it should

mainly focus on liberating territory that Russia has seized since February 24.

But a complete Ukrainian victory also entails freeing the parts of the country

Russia has occupied since 2014, including Crimea. It means that Ukraine

must reclaim its territorial waters and exclusive economic zones and complete

the Black Sea and Azov Sea without any compromises or conditions.

Russia's president

has increasingly staked his regime on conquering Ukraine, sacrificing his country's

economic growth and international reputation in the process. Such a broad

defeat could push Russian elites to remove him from power. Indeed, as the mass

of Putin's failures and Ukraine's achievements grow, Putin's fall may

become inevitable. This scares confident leaders, who worry that a power

struggle in Russia will breed dangerous instability. But it's hard to

imagine a Russia more difficult than the one led by Putin, given all the havoc

he has wreaked—in Ukraine and throughout the world. The international

community should welcome his departure.

Advantage, Ukraine

Many Western

observers believe Ukraine will have to cede territory to Russia if it wants

peace. They are wrong; territorial gains will only embolden the Kremlin. Putin

decided to attack eastern Ukraine in 2014 because he succeeded in occupying

Crimea. He invaded the entire country because he managed to establish proxy

puppet regimes in the Donbas. Partial success motivates Putin to continue his

campaigns and seize more territory. The only way to stop the war and deter

future aggression is for the invasion to end with an unequivocal Russian

failure.

Winning everywhere

might seem overly ambitious, and it certainly won't be easy. But it is far more

possible than most outside observers realize. Ukraine, after all, has

repeatedly outperformed international expectations. In the war's opening

weeks, the country stopped Russia's blitzkrieg against the capital

and forced Moscow to retreat. Putin responded to this defeat by declaring

that he would regroup and focus on conquering the Donbas, which are filled with

the kind of open fields that favor Russia and its heavy artillery. And yet

Ukraine steadily wore Russia down, making it pay for every tract of land with

massive casualties. Eventually, Russia was forced to halt.

Ukrainian soldiers

put ammunition into a crate at a front line near Toretsk

in the Donetsk region on 12 October:

Ukrainians have also

proved that they can make Russia not just retreat but run. Ukraine's lightning

offense across Kharkiv in late September prevented Russia from even trying to

annex the province. Its early October victory in Lyman

has made Russia's position in the Donbas deeply uncertain. Ukraine is now

liberating villages adjoining Luhansk, the only Ukrainian province that Russia

entirely seized after February 24. And Ukrainian soldiers are moving closer to

Kherson, the first major city that Russia seized in its 2022 offensive.

Ukraine's repeat

successes are not coincidences. The country's military has structural

advantages over its Russian adversary. The Russian military is extremely hierarchical and overly centralized; its

officers cannot make critical decisions without permission from senior leaders.

It is awful at multidirectional planning, incapable of focusing on the

frontline without distracting from its operations in another. Ukraine, by

contrast, is quick to adapt, with a NATO-style "mission command"

system that encourages lower-ranking officers and sergeants to make decisions.

Ukraine has also carried out many successful multidirectional attacks. For

example, the country's counteroffensive in the south diverted critical Russian

resources away from Kharkiv, allowing Ukrainian units to advance easily.

Ukraine's advantages

are unlikely to dissipate. The Russian military continues to make unsound

decisions. A critical number of junior Russian officers were killed in the

war's first months; without them, Russia will find it harder to organize and

train its troops. Unlike Ukraine, Russia does not have a strong core of

noncommissioned officers who can help with the war. Although Russia's mass

mobilization will likely have an impact—the influx of new soldiers will

complicate Ukraine's efforts to advance—it will mostly yield inexperienced and

poorly trained men who neither want to fight nor know how to fight. Many will

run as they experience the shock of battle, coming under loud and devastating

artillery attacks. Many will die.

Bridge repair work is

seen on the collapsed part of the Kerch Strait bridge in Crimea:

Ukraine has also suffered

severe casualties, and its soldiers will continue to fall in combat. But unlike

the Russians fighting a "special military operation" fueled by

Putin's imperial delusions, the Ukrainians are fighting a total war to save

their country. Ukraine continues to see a steady stream of motivated fighters;

Russia continues to see long lines of men fleeing the country. Ukrainians

respect their military commanders and President Volodymyr Zelensky, and the

military protects its soldiers and promotes its brightest. The Russian army,

however, mistreats its troops, showing little regard for their lives. This

helps explain why Russian soldiers fled from Kharkiv and are now running in

parts of the Donbas and Kherson. Armies that run once tend to run again.

Quality And Quantity

Russia, indeed has

more weapons than Ukraine. Despite months of losses, Moscow still possesses

sizable stockpiles of missiles, guns, and ammunition that it can use to attack

Ukrainian forces. But this is not the advantage that it may seem. Regarding

using weapons, Russia and Ukraine follow different philosophies: Ukraine

focuses on high-tech and precision-driven equipment, whereas Russia relies on

high-quantity but lower-precision systems. Because precision substantially

affects accuracy, Ukraine can do more with less. If Ukraine continues to

receive a steady supply of Western weapons, it will be able to negate Russia's

numerical superiority.

Long-range firepower

is one critical capability where Ukraine will need more support. The country

must have enough weapons and ammunition to outfit its brigades with artillery

systems and multiple rocket launchers that can reach behind enemy lines,

hitting ammunition depots and making it extremely hard for Russia to send

reinforcements. Ukrainian forces have already successfully used such Western

systems, especially U.S.-made High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS).

But they will need even more equipment, including new, powerful weapons that

can hit deeper targets. If supplied, U.S.-made Army Tactical Missiles Systems

(ATCAMS) would prove particularly useful by allowing Ukraine to destroy Russian

battlefield positions up to 190 miles away. Ukraine must also have enough

weapons to simultaneously meet its operational requirements in at least two or

three regions, such as the east and south, while holding off the Russians.

Suppose Ukraine maintains an initiative and equally strong presence along the

war's long lines of contact. In that case, it can be assured of hitting

Russia in the areas where the Russian military is weakest.

But firepower is not

the only thing that Ukraine needs. To defeat Russia, Ukraine must be equipped

with more tanks and armored personnel carriers, which it used to significantly

affect in retaking Kharkiv Province. Ukrainian artillery units will also need

enough counterbattery radars, such as AN/TPQ radar systems, to swiftly detect

incoming fire. Ukraine needs more midrange air-defense units, such as the

National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMS), to protect its

troops and cities as they come under Russian bombardment. It will need to

sustain all these capabilities, so Ukraine's military must set up ammunition

and spare-parts facilities around its western borders. It must also build

comprehensive support facilities closer to the frontlines, where it can quickly

repair damaged weapons and equipment.

Ukraine has already

proved capable of downing Russian aircraft and defying predictions that Russia

would gain air superiority. Ukraine has also been able to damage the Russian

navy. The country's successful strike against Russian navy installations and

vessels, including the Moskva cruiser—the Russian Black Sea

Fleet's flagship—helped push Russia's ships farther away from the Ukrainian

coast. But sea access denial is an ongoing process, not a one-time achievement,

and Ukraine will need help if it wants to break Russia's blockade fully. The

West must supply the country with more coastal missiles, unmanned systems, and

detailed intelligence so Ukraine can eventually regain full access to its seas.

The West has reasons

to supply Ukraine that go beyond just this conflict. The war has given NATO a

rare chance to test its equipment in a real-time, high-intensity operational

environment. The United States and Europe can learn invaluable lessons from how

their weapons perform, and the more gear they provide, the more knowledge they

will acquire. Together, the West and Ukraine can figure out which weapons

systems need tweaking and which work best, and Kyiv can use the most effective

ones to keep pushing Russian forces back.

Saving The World

Putin is aware that

Russia is losing on the battlefield, and his not-so-veiled threats to use

nuclear weapons are a transparent attempt to halt Western assistance. He likely

knows that these threats will not stop Ukraine. But if Putin follows through on

them, it would deter the West from helping Ukraine and shock Kyiv into

surrendering.

However, breaking the

nuclear taboo would devastate the Kremlin in ways that simply losing the war

wouldn't. Tactical nuclear weapons are difficult to target, and the fallout can

extend in unpredictable directions, meaning a strike could seriously damage

Russian troops and territories. Ukrainians would also fight on even if hit by a

nuclear attack—for Ukrainians, there is no scenario worse than Russian

occupation—so such a strike would not lead to Kyiv's surrender. And if Russia

goes nuclear, it will face various severe retaliatory measures, some of which

may have consequences beyond the battlefield. China and India have so far

avoided backing Ukraine or sanctioning Russia, but if the Kremlin launches a

nuclear attack, Beijing and Delhi may join the West's anti-Russian coalition,

including by implementing severe sanctions and banning relations with Russia.

They may even provide military assistance to Ukraine. For Russia, then, the

result of nuclear use would be not just defeat but even more international

isolation.

Putin, of course, is

capable of making terrible choices, and he is desperate. Neither Ukraine nor

the West can discount the possibility that he will order a nuclear attack. But

the West can deter him by clarifying that, should Russia launch such a strike,

it will directly and conventionally enter the conflict. Avoiding NATO

involvement is one of the main reasons Putin continues to threaten a nuclear

attack—Putin knows that if Russia cannot prevail against Ukraine, it has no

chance against NATO—and he is, therefore, unlikely to do something that would

bring the bloc in. That's especially true given the speed with which NATO would

win. Ukraine's counteroffensive is moving comparatively slowly, giving Putin

space to use his propaganda apparatus to manage public perception of the

events. Once NATO joined, he would have no time to shield his reputation from

the Russian military's stunning collapse.

NATO has no shortage

of ways to threaten Russia seriously without using nuclear weapons. It might

not even need a land operation. The Western coalition could credibly tell the

Kremlin that it would hit Russian capabilities with direct missile strikes and

airstrikes, destroying its military facilities and disabling its Black Sea

Fleet. It could threaten to cut all its communications with electronic warfare

and arrange a cyber-blackout against the entire Russian military. The West

could also threaten to impose totalizing and complete sanctions (no exceptions

for energy buys), which would quickly bankrupt Russia. Especially if taken

together, these measures would cause irreparable, critical damage to the

Russian armed forces.

What the West should

not and cannot do is be cowed by Russia's nuclear blackmail. If the West stops

aiding Ukraine because it fears the consequences, nuclear states will find it

much easier to impose their will on nonnuclear ones in the future. If Russia

orders a nuclear strike and gets away with it, nuclear states will have almost

automatic permission to invade lesser powers. In either scenario, the result

will be widespread proliferation. Even poorer countries will plow their

resources into nuclear programs for an understandable reason: It will be the

only sure way to guarantee their sovereignty.

Crime And Punishment

With enough Western weapons,

Ukraine will continue breaking through Russian defenses. It will use long-range

rockets to destroy command posts, depots, and supply lines, making it

impossible for Russia to reinforce its battered troops properly. It will shoot

down Russian aircraft, preventing the Russian air force from defending its

positions. It will keep sinking Russian naval craft. And it will be helped

along the way by the Russian military's many deficiencies: its intense

centralization, emphasis on punishing its forces for mistakes rather than

learning from them, and its highly inefficient combat style. In the face of

mounting setbacks, Russian morale will eventually collapse. The country's

soldiers will be forced back home.

Ukraine's liberation

of Crimea and the parts of the Donbas that Russian proxies seized in 2014 will

come next. And after Ukraine's victories elsewhere, these operations are

unlikely to be all that taxing. When Ukrainian forces reach those regions, the

Russian military will likely be too exhausted to defend them seriously. Many

Russian-controlled Donbas male residents will already have been killed on the

frontlines. The survivors (which will likely include most of the region's

remaining male population) are unlikely to be loyal to the Kremlin, given what Putin

has put them through. Some Western observers may consider Crimea a special case

and encourage Ukraine not to press forward. Still, although it has been under

Russian control longer, its annexation remains as illegal today as it was in

2014. International law should know of double standards.

The liberation of

Crimea and the Donbas should include a reintegration campaign. Because the

periods of Russian occupation, with their attendant aggressive propaganda, have

lasted so long, residents will need to receive social, legal, and economic

assistance from Ukraine as part of reconciliation efforts. These efforts will

make for a more delicate operation. As the Ukrainian government restores its

governance, it must show residents that Kyiv can provide stability and the rule

of law, unlike Moscow.

Meanwhile, the world

must prepare for what Ukrainian wins in these long-occupied regions will mean

for Putin. Annexing Crimea and creating puppet states in the Donbas were two of

his signature achievements, and his regime may not survive losing them. The

world may want to prepare even before Ukraine moves into Crimea; Putin's regime

will be endangered if Ukraine retakes just the areas Russia seized after

February 24. Losing almost all the land it just annexed, would be a humiliating

failure for Moscow. It may get Russia's elites to finally realize that their

president's obsession with war is deeply unproductive and will rise against

him. It would not be the first time a leader has been pushed out of power in

Russian history.

Germany's delayed

delivery of an IRIS-T Surface-Launched-Missile (SLM) system. It is the first of

four methods expected to be delivered to Ukraine next year:

Once Putin is gone,

the world must focus on making Russia pay restitution. Moscow should be held

fully responsible for its damage to Ukraine, providing reparations to the

country and the Ukrainian people. Ideally, after regime change, Russia will do

this of its own volition. But if it doesn't, the West can redirect hundreds of

billions of dollars in frozen Russian assets to Ukraine as collateral. Russia

must release all prisoners of war and all Ukrainian civilians it has detained

or forcibly moved to Russia. It needs to return the thousands of children it

kidnapped during the invasion and occupation. Finally, Ukraine and its partners

must demand that Moscow hand Putin, other senior Russian leaders, and any figures

involved in wartime atrocities to a globally recognized criminal tribunal. The

West should refuse to lift any sanctions on Moscow until these demands are met.

They must demonstrate that extreme aggression, genocide, and terror are

unacceptable.

This program of

penance and justice may seem frightening to international leaders, who believe

it could cause instability in Russia. Some analysts even say that the Russian

Federation could disintegrate, leading to catastrophic consequences for the

rest of the world. Many international leaders had similar fears when the Soviet

Union collapsed, including former U.S. President George H. W. Bush, who

traveled to Ukraine in 1991 to try to stop the country from seceding from

Russia. But these leaders were wrong. Despite the war, Ukraine has become a

symbol of democracy worldwide. Many other post-Soviet states have grown far

wealthier and freer since 1991. If Russia were weakened today, the net outcome

would be similarly positive. Its reduced capabilities would make it harder for

Moscow to threaten as many people as it does now. And it is simply unjust to

try to keep the country's residents under the foot of a paranoid, genocidal

dictator.

Indeed, Ukraine may

well need a weaker Russia to protect its wins. At a minimum, it will need

substantive regime change to feel safe. Putin's commitment to eliminating

Ukraine and forcing it back into his empire is so extreme that a Ukrainian

victory cannot be secure as long as he is in power. And Russia is full of

ruthless leaders with a similarly distorted moral compass and a similarly

imperialistic worldview. Until Ukraine is allowed to join NATO, it will

have to build a powerful military, becoming—as Zelensky put it—a "big

Israel." This is not ideal, and it will be costly. Ban equally in the near

term; it will be the only way a victorious Ukraine can ensure long-lasting

peace.

Promising today is

that dozens of Ukraine's allies have pledged to send more military aid

to Ukraine after more than 50 western countries met In Brussels on

Wednesday, 12 October. Ukraine's defense minister, Oleksiy Reznikov, lauded the

arrival of the first of four Iris-T defense systems from Germany and

"expedited" delivery of the sophisticated national advanced

surface-to-air missile systems (Nasams) from the US.

"A new era of air defense has begun in Ukraine," Reznikov

tweeted. "Iris-Ts from Germany

are already here. Nizams are coming. This is only the beginning. And we need

more." The UK has said it will donate cutting-edge air defense

weaponry capable of shooting down cruise missiles. It did not say how many Amraam rockets would be sent to Ukraine but said they would

be used with Nizams.

For updates click hompage here