By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

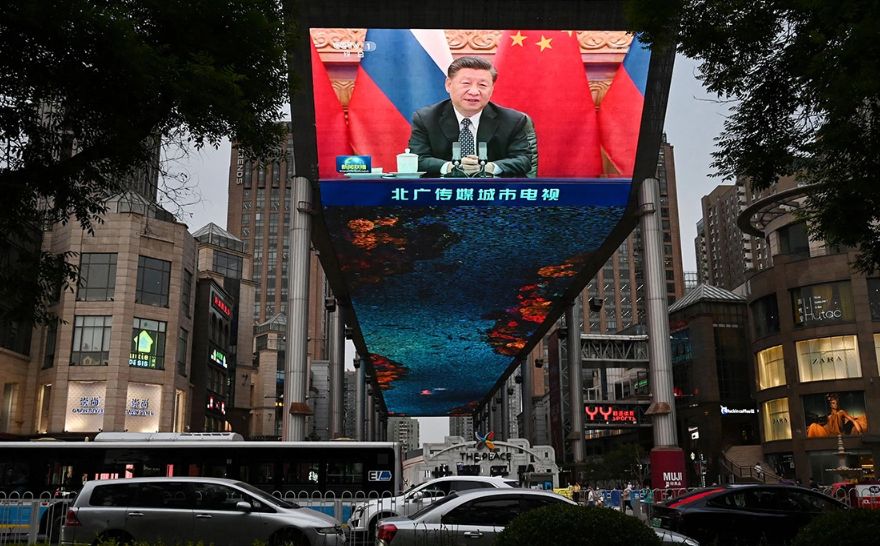

How China Manipulates The Media

Over the past decade,

Beijing has invested heavily in upgrading its major state media outlets, such

as China Global Television Network (CGTN), Xinhua News Agency, and China Radio

International (CRI), to make them seem more professional. It has tried to

normalize them to audiences as little different from the BBC, CNN, or Al

Jazeera—most likely Beijing’s preferred model—a station based in an

authoritarian state but producing respected work.

For years in the

2010s, China hired respected foreign reporters to staff bureaus of outlets such

as CGTN in the United States, Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia, and other places,

and initially gave them a bit of room to cover exciting stories—as long as

those did not directly affect China. The global journalism market is terrible:

Between 2001 and 2016, newspaper publishing in the United States lost more than half the jobs in the industry, a

higher rate of loss than in coal mining, not

precisely an industry of the future. China’s outlets found many

willing and credentialed reporters to join. Today, the Chinese government’s

funding for state media dwarfs any other country’s state media funding,

including that of the United States. In 2018, CGTN reportedly spent around $500

million to promote the

network in Australia alone; it has also engaged in extensive promotion in

Europe and North America.

To expand its

influence within the domestic politics and societies of other countries, China

in the past decade dramatically expanded other tools of persuasion as well,

which I chronicle in my new book, Beijing’s Global

Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World. These have included using disinformation online,

payments to politicians to spout pro-China ideas, control of Chinese student

associations in many countries, funding programs at universities, and

other tactics.

But state media has

been central to China’s efforts to influence other countries, control

information about and protect the party, and gain what Chinese leaders and

officials have called “discourse power” to amplify China’s narratives about its

policies, its party, its leader, and its role in the world. Beijing’s cause is

helped by a global environment in which resources for quality media are

decreasing, democratic and authoritarian leaders are demonizing media, and

publics’ trust in journalism is falling. Such circumstances would seemingly

make it easier for Chinese outlets to win readers, listeners, and viewers.

Yet China’s state

media (excluding local-language Chinese media within specific countries), other

than Xinhua, has hardly been a triumph for President Xi Jinping and the Chinese

Communist Party (CCP), even with money gushing in.

Indeed, Xi’s bold

goal to wield state media power globally, a priority noted in CCP documents,

has not worked to significant effect—and that goal is fading even faster as the

world sees the failure of Xi’s China model, which was heavily advertised in

state media abroad. China’s global influence efforts, fueled in part by state

media, have not prevented the public in many countries from souring on Beijing’s

increasingly assertive diplomacy; being angry at the initial cover-up of

COVID-19; fuming at how China increasingly uses economic coercion against other

states, even tiny ones like Lithuania; or seeing the flaws in China’s politics.

In public opinion studies released in 2020, 2021, and 2022, such as those conducted by Pew, opinions of China in states from Sweden to South

Korea to Australia turned sharply negative. Negative views of China reached

historic highs in many forms.

What evidence shows

how China has failed to use state media effectively? China’s most

prominent state media outlets, other than Xinhua, have not sold many programs

abroad or gained noticeable audience shares in most countries. China’s training

programs for journalists, while rapidly expanding (at least before zero-COVID),

have not changed how foreign reporters cover China.

Take one example, the

appeal of Chinese TV show exports globally. South Korea, a far smaller country,

regularly outpaces the value of Chinese TV show exports. South Korea also has

exported increasingly successful films and scripted shows—as well, of course,

as one of the most popular bands in the world.

Similarly, while

China ranked second in the Lowy Institute’s annual Asia Power Index, Beijing’s high numbers come primarily from

its high rankings in economic relationships, diplomatic influence, and future

power. The Asia Power Index’s measures of China’s influence over the region’s

information landscape, including the impact from state media, show far less

impressive results. The Lowy study uses influence maps based on internet search

trends to assess Asians’ interest in regional media outlets. These maps have

shown that CGTN is only the 10th-most popular broadcaster in the Asia-Pacific,

and its reach is a fraction of outlets such as CNN. The maps show that

CGTN’s “reach is inconsequential,” as noted by the coordinator of the influence

maps. Other Chinese outlets save Xinhua also fare poorly on these influence

maps.

Using the Freedom of

Information Act, I obtained more than 20 studies, produced by Gallup as a

contractor for the U.S. government, of viewing habits in countries in Africa,

Southeast Asia, and South and Central Asia, among other regions. They generally

show that although Chinese state media are widely available in many countries,

they usually attract minuscule viewership or listening numbers. In Laos, for

instance, a country on China’s border with a growing population of

Chinese speakers, one Gallup study of viewership in Laos found only 1.2 percent

of the country’s population regularly watched Chinese broadcasting, a much

lower figure than those who watched Voice of America or Radio Free Asia or Thai

channels.

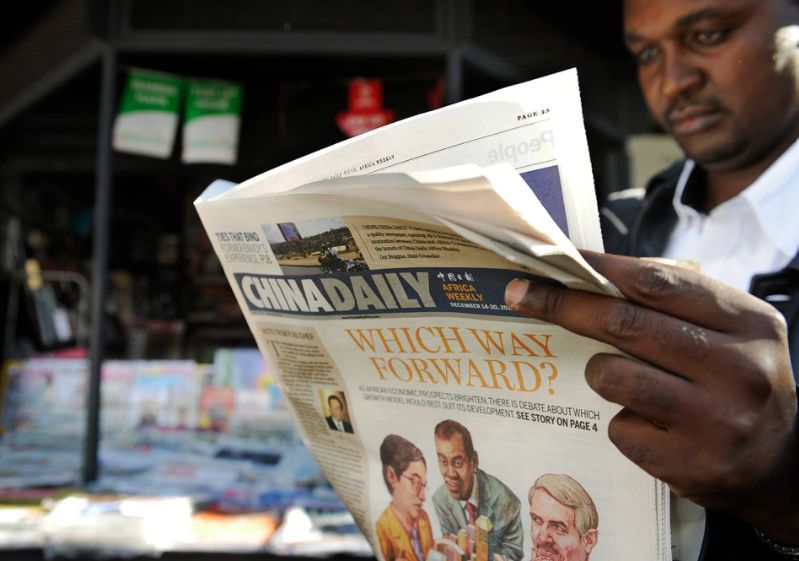

Chinese media outlets’ audience

shares and perceived credibility lag behind local news sources, the BBC, and

other Western broadcasters, even in regions like Africa, where public opinion

toward China is not as harmful. In Ivory Coast, for instance, CRI has expanded

its programming. Still, the Gallup study I obtained shows that CRI was listened

to by less than 1 percent of Ivorians weekly, among the worst figures of any

radio station’s reach in the country. (The BBC was listened to by

13.7 percent of Ivorians.) In Nigeria, a bigger target for Chinese state

media, CGTN and CRI performed abysmally in a similar Gallup study. In Nigeria,

CGTN had 3.7 percent viewership, a quarter of the audience of the BBC.

Even in Kenya, the

hub of CGTN operations in East Africa, Chinese outlets have fared poorly.

Studies suggest most Kenyans who consume news do not even

utilize Chinese state media.

These figures are

consistent with the still-low audience shares of CGTN, CRI, and state media

outlets, save Xinhua, in many other regions of the world. Chinese broadcast and

radio state media outlets in Asia have yet to reach a large audience. A Gallup

study of the weekly reach of television stations in Vietnam found that CGTN was

only watched by 0.7 percent of Vietnamese adults, far less than the BBC,

CNN, France’s TV5 Monde Asie, and South

Korea’s Arirang TV. Two-thirds of Vietnamese who watched the BBC said they

trusted that outlet greatly, but only about 7 percent who surveyed CGTN said

the same.

In Western

democracies, Europe, and North America, CGTN has largely fizzled. In the United

Kingdom, which has a sizable audience of people fluent in Chinese, similarly,

China ranked second in the Lowy Institute’s annual Asia Power Index is a fraction of outlets such as CNN. The

maps show that CGTN’s “reach is inconsequential,” as noted by the

coordinator of the influence maps. Other Chinese outlets save Xinhua also

fare poorly on these influence maps.

Using the Freedom of

Information Act, I obtained more than 20 studies, produced by Gallup as a

contractor for the U.S. government, of viewing habits in countries in Africa,

Southeast Asia, and South and Central Asia, among other regions. They generally

show that although Chinese state media are widely available in many countries,

they usually attract minuscule viewership or listening numbers. In Laos, for

instance, a country on China’s border with a growing population of

Chinese speakers, one Gallup study of viewership in Laos found only 1.2 percent

of the country’s population regularly watched Chinese broadcasting, a much

lower figure than those who watched Voice of America or Radio Free Asia or Thai

channels.

A study found

that CGTN was being watched by a minimal number of Britons—even before the

British government kicked CGTN off the air in 2021 because it did not have

autonomy from the Chinese state. Similarly, though CGTN launched a European

subsidiary in 2019 via its London hub, it has made few inroads into the

continental European market. And throughout Latin America, including in several

large democracies, CGTN’s Spanish-language channel has significantly

expanded the number of households in which it is available over the past decade

but has not proved popular. A comprehensive study of CGTN-Español, CGTN’s Spanish-language

channel, by Peilei Ye and Luis A. Albornoz,

suggests that the Chinese government usually releases information only about

the size of the audience CGTN potentially reaches—the number of households it

is available in—and not the actual audience, most likely because the actual

audience size is embarrassingly low.

Why has China’s state

media—other than Xinhua, which I’ll come to later—failed so badly? In the Xi

era, it simply produces content that is too boring, staid, and timid. In an era

more restricted than the 1990s, one in which China has today become much more

authoritarian, state media reporters now instinctively tailor their stories to

ensure they do not anger anyone at headquarters back in Beijing, which makes

for weak and bland reporting.

CGTN reporters note

that while they had more freedoms six or seven years ago, the most significant

focus is whether the stories will prove acceptable to the top leadership in

Beijing rather than news consumers in foreign countries. This is “domestic

signaling,” as the Guardian called it in an exposé of China’s soft- and

sharp-power efforts—“telegraphing messages [via reporting in state media]

that demonstrated loyalty to the party line to curry favor with senior

officials.”

This does not make

for exciting journalism. Further, a considerable part of the state media’s efforts

to reach foreign audiences was designed to advertise China as a developmental

success story—Xi was the first recent Chinese leader to embrace a Chinese model

of development openly. But the past three years of China’s disastrous

zero-COVID strategy, protests, supply chain disruptions, and severe economic

slowdowns—

All visible to

the world, and even more so now that protests are raging in China—have

undermined that central prong of the state media’s foreign messaging.

Chinese state outlets

will find it harder to gain audiences as many leading democracies put

roadblocks in their way. These have included the United Kingdom pulling CGTN’s license

and the United States forcing state media to register as agents of foreign influence, which drives away U.S.

national and Chinese national reporters who do not want to be tagged as

influence agents. Some democracies, such as Australia and Singapore, have

created commissions or legislation to examine foreign investment and influence

inside their borders closely. European states, too, are assessing ways to

monitor better foreign investment and impact in the media and information

sectors.

Xinhua, alone

among China’s most prominent state media outlets, has expanded

significantly while also boosting its global audience and gaining some

credibility. Beijing has placed a high premium on modernizing Xinhua and

getting foreign news outlets to use Xinhua stories by signing content-sharing

deals, legitimizing Xinhua to some editors and readers. Xinhua has inked many

such agreements, including stories in languages other than Chinese. Because it

covers so many topics unrelated to China, its reporters sometimes have more

room from Beijing to operate. It is likely that, in the next decade, with the

pandemic forcing more outlets to cut staff and with media outlets around the

globe continuing to suffer financially, the appeal of signing deals with

Xinhua, a cheap or free newswire, will only increase. Indeed, Xinhua could

become China’s most influential information weapon.

As of this writing,

Xinhua still needs to forge more connections to consistently write the first

draft of global news stories, as wires do. Since some major outlets such as the

BBC and the New York Times do not regularly use Xinhua stories,

distrusting them, Xinhua still does not circulate as widely among elite

publications as stories from Reuters, The Associated Press, or Bloomberg.

But that may be changing rapidly. In recent years, Xinhua has inked cooperation

agreements with major global and regional newswires, including Agence France-Presse; news services in Australia; Germany’s Deutsche

Presse-

Agentur; Poland’s Polish

News Agency; Class Editori in Italy; Le Soir in Belgium; Athens News Agency in Greece; RAI, Italy’s

public broadcaster; and ANSA, Italy’s leading wire service.

And on many

occasions, in places with a massive workforce advantage,

like Southeast Asia and China itself, Xinhua is beating competitors to stories

or is covering stories competitors do not have the resources to cover. As

Xinhua grows (and offers its service accessible to many outlets in developing

countries), and as other newswires struggle financially, the Chinese newswire

will get to more stories first—and earn editors’ and publishers’

trust. It is rapidly opening bureaus. By early 2021, Xinhua had a reported 181

bureaus globally. This would give Xinhua a reach close to that of The

Associated Press, which has around 250 bureaus worldwide, or the BBC, which is

a giant in Africa, Asia, and other regions. Meanwhile, the Chinese newswire has

a massive advantage over most of its competitors because it does not have to

make a profit.

Xinhua also is

attempting to boost its credibility in other ways in Southeast Asia and other

areas physically close to China or where populations have relatively positive

images of China. In Southeast Asia and Africa, where Xinhua has poured

resources into expansion, the Chinese state newswire can cover stories that may

not get mentioned by other media organizations include Reuters, The

Associated Press, Agence France-Presse, and prominent

international newspapers with foreign staff. One former U.S. official

analyzing China’s expanding state media called this a “hyperlocal

approach,” a strategy focused on offering detailed stories in regions that some

global outlets ignore.

Eventually, suppose

governments and news organizations do not put roadblocks in their place. In

that case, via content-sharing deals, Xinhua copy will appear in more and more news

outlets, shaping public and elite opinion in many countries, as it already does

in places such as Thailand. A range of evidence shows Xinhua’s growth

in size and influence. There, Xinhua has signed content-sharing deals with many top Thai publications, including

those of the Matichon Group, the most-respected Thai-language news

organization. These deals have allowed China to shape news narratives in

Thailand, where many more Thai outlets now run Xinhua copy. Overall, not only

is China portrayed more positively in the Thai media than in the past,

according to many Thai journalists, but serious critiques of China are

vanishing from many Thai outlets.

A range of evidence

shows Xinhua’s growth in size and influence. The Lowy Institute’s

maps of digital influence in Asia show Xinhua is making inroads across the

region. Indeed, the maps show that Xinhua has become the second-most-influential

news agency regionally, behind only The Associated Press, and that Xinhua is

making significant gains in influence in the media environment of several

Northeast Asian and Southeast Asian states. And unlike with, say, a television

station that a viewer has to turn on actively and probably knows the channel,

most print or online readers do not check the bylines of news

articles—making it easier for Xinhua copy to slip through to readers.

Notably, media

outlets have been signing deals to carry Xinhua even in countries where the

U.S. government—and private nonprofits hailing from democratic states—have

invested heavily in promoting the creation of a vibrant local media. In

Afghanistan, for instance, where donors, including the United States, have plowed

money into the local press, an International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

report shows that Xinhua has inked contracts with 25 to 30 Afghan media

outlets. These deals include the ones with the most major television stations

and websites in the country.

The IFJ report notes

that China’s content-sharing deals have helped reshape journalists’

messaging about Beijing in multiple countries, including those known for robust

local journalism. Its survey of Philippine journalists found that China’s

increasingly close links with the Philippines’ state television, the Philippine

News Agency, and the Philippine Information Agency, built through

content-sharing and training programs, affect Philippine news outlets’ coverage

of China.

Indeed, China’s closer

links to Philippine media and the spreading use of Xinhua in the Philippines

are depriving Philippine news consumers of independent reporting on Beijing.

These shifts are depriving Filipinos of separate coverage even as

Beijing squeezes the Philippines into the South China Sea, even though the

population in the Philippines has not become markedly more pro-China. “The way

they write their stories now, they reflect how Xinhua or the state media in

China is writing their stories,” one Philippine journalist told IFJ. “It’s

normally propaganda.” Another told IFJ, “Instead of getting insights on

journalism from free countries like the United States, United Kingdom, Western

Europe, and even Japan, they [journalists in the Philippines] are learning

state control.”

For updates click hompage here