The growing trend of Vaccine Nationalism

Today the World

Health Organization has warned against “vaccine nationalism”, cautioning

richer countries that if they keep treatments to themselves they cannot expect

to remain safe if poor nations remain exposed.

As global cases of

Covid-19 passed

19 million on Friday, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said it would be

in the interest of wealthier nations to help every country protect itself

against the disease.

“Vaccine nationalism

is not good, it will not help us,” Tedros told the Aspen Security Forum in the

United States, via video-link from the WHO’s headquarters in Geneva.

“For the world to

recover faster, it has to recover together, because it’s a globalized world:

the economies are intertwined. Part of the world or a few countries cannot be a

safe haven and recover.

“The damage from

Covid-19 could be less when those countries who... have the funding commit to

this.”

Several countries are

racing to find a vaccine for coronavirus, which has killed more than 700,000

people globally.

There was some good

news as of late, this according to the recent Novavax results. However it is no secret

that Scientists fear that the current pandemic could lead to a geopolitical

fight over vaccines. And that ‘vaccine nationalism’ threatens global plan

to distribute COVID-19 shots fairly.

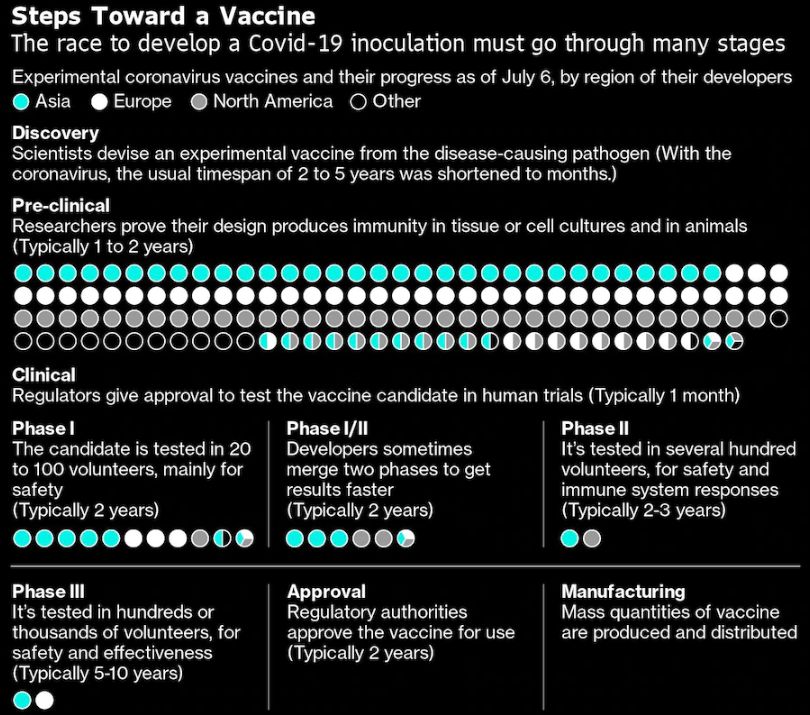

The race

to develop an inoculation against Covid-19, involving vaccine developers in

more

than 30 countries, entails cross-border collaboration but also high-stakes

competition. Some countries are using their research dollars to try to buy the

first place in line for supplies in the event an experimental vaccine proves

effective. Public health specialists warn that such vaccine nationalism could

result in the pandemic lasting

longer, by preventing the most efficient allocation of shots to prevent

Covid-19.

The drug companies

find themselves caught in the middle. While eager to bring products to market

as quickly as possible, they face risks in moving too quickly in order to fit

certain agenda's like for example the US

election calendar

As part of its Operation

Warp Speed aimed at advancing the development of coronavirus

countermeasures, the U.S. has committed billions of dollars of support to

vaccine companies, with the priority being protecting American citizens first.

Officials have placed advance orders for hundreds of millions of doses of

vaccines, in the event they prove effective, with the aim to deliver sufficient

supply to cover the U.S. population by January 2021. The approach is in keeping

with the U.S. government’s purchase of 500,000 doses of the Covid-19 treatment

remdesivir, which is all of the manufacturer’s production for July and 90% for

August and September.

It escaped no one

that the proposed deadline of Operation Warp Speed also intersected nicely with

President Trump’s need to curb the virus before the election in November.

The ensuing race for

a vaccine, in the middle of a campaign in which the president’s handling of the

pandemic is the key issue after he has spent his time in office undermining

science and the

expertise of the federal bureaucracy, is now testing the system set up to

ensure safe and effective drugs to a degree never before seen.

Under constant

pressure from a White House anxious for good news and a public desperate for a

silver bullet to end the crisis, the government’s researchers are fearful of

political intervention in the coming months and are struggling to ensure that

the government maintains the right balance between speed and rigorous

regulation, according to interviews with administration officials, federal

scientists and outside experts.

Who besides the U.S.?

The U.K. has already

secured the

highest number of potential Covid-19 vaccine doses per capita, ahead of the

U.S., having signed a deal with GlaxoSmithKline Plc and Sanofi for as many as

60 million doses. The Serum Institute in India is developing one of the leading

Covid-19 vaccine candidates, and its owner has signaled that most of the

initial supply of a successful shot would be distributed within India. Japan

is trying to lock up supplies, having made a deal with Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech

SE for 120 million doses of the vaccine they’re developing. Germany, France,

Italy and the Netherlands have signed an initial contract for pre-orders of 300

million vaccine doses with AstraZeneca that would be available to all members

of the European Union.

Can vaccine nationalists guarantee first access to a

vaccine?

That depends. What

may prove more important than who has invested in a vaccine is where it is

manufactured. Pharmaceutical companies are preparing for the possibility that

the governments in control of manufacturing locations will demand sufficient

doses to cover their population before allowing exports. This would hardly be

unprecedented. This year, under the pressure of the pandemic, more than 90

states and territories have placed export curbs on medicines and medical

supplies. Anticipating export bans, vaccine developers are working to build

parallel manufacturing facilities in multiple countries, but it’s an expensive

endeavor with large financial risks, given that the vast majority of

experimental vaccines don’t pan out. In its agreements to fund vaccine

developers, the U.S. government has mostly negotiated manufacturing within the

U.S.

Who’s pursuing a different approach?

Three groups -- the

World Health Organization; the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations,

which works to advance new vaccines, and Gavi, a global non-profit group

focused on vaccine delivery -- have set up a program aimed at distributing

successful vaccines equitably around the world. Called the Covid-19 Vaccines

Global Access Facility (Covax), it calls on higher

income countries to invest $18 billion in about 12 experimental vaccines and

ensure that early access is shared around the globe when doses become

available. The intended appeal to rich countries is that the facility spreads

their bets across a variety of potential vaccines, any of which individually is

likely to fail. China’s President Xi Jinping has pledged to make any effective

vaccine against the coronavirus that is developed by China, a frontrunner in

the effort, accessible and affordable globally as a “public good.”

What are the prospects for those approaches?

More than 70

countries have indicated an interest in joining Covax,

though none have formally done so. The plan calls for donor countries to commit

by the end of August and provide an advance of 15% of the $18 billion. The

U.S., India and Russia have declined to participate. One issue around China’s

pledge to share any vaccine it develops is quality assurance. A 2018 scandal

that uncovered instances of Chinese vaccine-makers cutting corners in

production has given its industry a bad global reputation. After the incident,

Beijing passed new laws carrying hefty fines to police the industry.

What’s at stake?

Countries taking an

“every nation for itself“ approach are likely to reduce vaccine access for

other countries and drive up prices, leaving poorer nations especially in the

lurch. The concern is that the world will see a repeat of the situation in the

last pandemic, when rich nations purchased all the available supply of vaccines

against the H1N1 flu virus in 2009-10. Who gets access to vaccines and how much

they are willing to pay will have consequences for international relations in

coming years, with vaccines potentially becoming leverage in political

disputes. Beyond that, global health experts say, the pandemic will be

controlled fastest if a future vaccine is deployed in the most efficient way

possible -- with the first doses going to groups around the world that are at

the highest risk, such as medical workers, nursing home staffers and the

elderly, rather than to whole populations in the richest countries.

For updates click homepage here