By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The war about food supplies

The World Food Programme (WFP) calls for

the immediate reopening of Black Sea ports – including Odesa – so that critical

food from Ukraine can reach people facing food insecurity in countries

like Afghanistan, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen, where millions are

on the brink.

“Right now, Ukraine’s grain silos are full. At the same time, 44

million people worldwide are marching towards starvation,” said David Beasley,

Executive Director of the World Food Programme.

The UN’s food and agricultural price index reached about

160 points in March before falling 1.2 or 0.8% in April.

Cereal and meat price indices hit record highs in March. Wheat was trading in

Chicago at US$674c per bushel. Today it fetches US1,242c per bushel.

UN secretary-general António Guterres said shortages of grain and

fertilizer caused by the war, warming temperatures, and pandemic-driven supply

problems threaten to “tip tens of millions of people over the edge into food

insecurity,” as financial markets saw share prices fall heavily again on fears of

inflation and a worldwide recession.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has accused Russia of weaponizing

food and holding grain for millions of people

around the world hostage to help “break the spirit of the Ukrainian

people.”

“As a result of the Russian government’s actions, some 20 million tonnes of grain sit unused in Ukrainian silos as global

food supplies dwindle, prices skyrocket, causing more around the world to

experience food insecurity,” Blinken said.

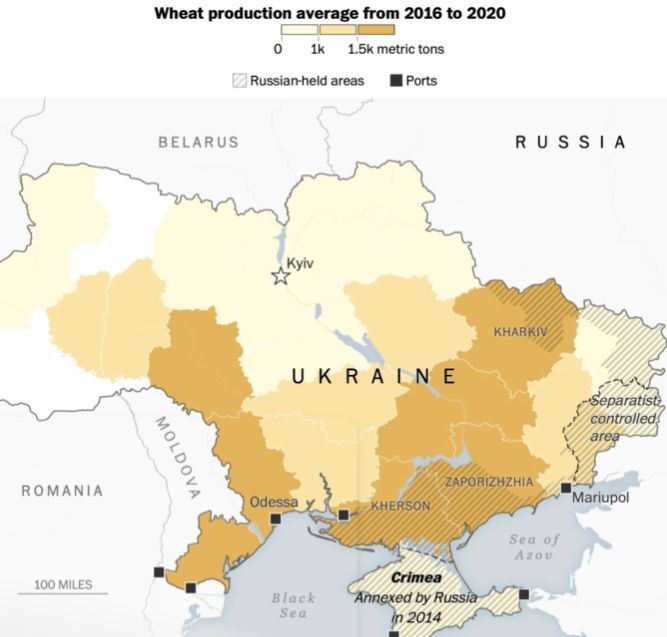

Accordingly, by invading ukraine, Vladimir

Putin will destroy the lives of people far from the battlefield and on a scale

that even he may regret. The war is battering a

global food system weakened by covid-19, climate change, and an energy shock. Ukraine’s exports of

grain and oilseeds have mostly stopped, and Russia’s are threatened. Together,

the two countries supply 12% of traded calories. Wheat prices, up 53% since the

start of the year, jumped a further 6% on 16 May, after India said it would

suspend exports because of an alarming heatwave.

The widely accepted idea of a cost-of-living

crisis does not begin to capture the gravity of what may lie ahead.

António Guterres, the un secretary-general, warned on 18 May that the

coming months threaten “the specter of a global food shortage” that could last

for years. The high cost of staple foods has already raised the number of

people who cannot be sure of getting enough to eat by 440m, to 1.6bn. Nearly

250m are on the brink of famine. If, as is likely, the war drags

on, and

supplies from Russia and Ukraine are limited, hundreds of millions more people

could fall into poverty. Political unrest will spread, children will be

stunted, and people will starve.

Russia and

Ukraine supply 28% of globally traded wheat, 29% of the barley, 15% of

the maize, and 75% of the sunflower oil. Russia and Ukraine contribute about

half the cereals imported by Lebanon and Tunisia; for Libya and Egypt, the

figure is two-thirds. Ukraine’s food exports provide the calories to feed 400m

people. The war is disrupting these supplies because Ukraine has mined its

waters to deter an assault, and Russia is blockading the port of Odesa.

The Russian navy has

established a blockade of Ukraine's Black Sea Coast:

Before the invasion, the World Food Programme

warned that 2022 would be a terrible year. China, the largest wheat producer,

has said that this crop may be its worst ever after rains delayed planting last

year. In addition to India’s extreme temperatures, the world’s second-largest

producer, a lack of rain threatens to sap yields in other breadbaskets, from America’s

wheat belt to the Beauce region of France. The Horn

of Africa is being ravaged by its worst drought in four decades. Welcome to the

era of climate change.

All this will have an unfortunate effect on the poor. Households in

emerging economies spend 25% of their budgets on food, and in sub-Saharan

Africa, 40%. Bread provides 30% of all calories. Many importing

countries cannot afford subsidies to increase the help to the poor.

Afghanistan: A family

collects their rations at a food distribution point

The crisis threatens to get worse. Ukraine had already shipped much of

last summer’s crop before the war. Russia is still managing to sell its grain,

despite added costs and risks for shippers. However, those Ukrainian silos

undamaged by the fighting are full of corn and barley. Farmers have nowhere to

store their next harvest due to starting in late June, which may rot. And they

lack the fuel and labor to plant the one after that. Russia, for its part, may

lack some supplies of the seeds and pesticides it usually buys from the

European Union.

Despite soaring grain prices, farmers elsewhere may not make up the

shortfall. One reason is that prices are volatile. Worse, profit margins are

shrinking because of the surging prices of fertilizer and energy. These are

farmers’ main costs, and both markets are disrupted by sanctions and the

scramble for natural gas. If farmers cut back on fertilizer, global yields will

be lower at just the wrong time.

"Russia has launched a grain war, stoking a global food

crisis," Berlin's

top diplomat said. "It is doing so at a time when millions are already

being threatened by hunger, particularly in the Middle East and Africa."

The UN says around 20

million tonnes of grain are currently stuck in

Ukraine:

The response from worried politicians could make a bad situation worse.

Since the war started, 23 countries have declared severe restrictions on food

exports that cover 10% of globally traded calories. If trade stops, famine will

ensue.

The scene is set for a blame game, in which the West condemns Putin for

invading, and Russia decries Western sanctions. The disruptions are due to

Putin’s invasion, and some sanctions have exacerbated them.

Instead, states need to act together, starting by keeping markets open.

This week Indonesia, the source of 60% of the world’s palm oil, lifted a

temporary ban on exports. Europe should help Ukraine ship its grain via rail

and road to ports in Romania or the Baltics, though the most optimistic

forecasts say that just 20% of the harvest could get out that way. Importing

countries need support, too, so enormous bills do not capsize them. Emergency

supplies of grain should go only to the very poorest. For others, import

financing on favorable terms, perhaps provided through the imf, would allow donors’ dollars to go further. Debt relief

may also help to free up vital resources.

There is scope for substitution. About 10% of all grains are used to

make biofuel, and 18% of vegetable oils go to biodiesel. Finland and Croatia

have weakened mandates that require petrol to include fuel from crops. Others

should follow their lead. An enormous amount of grain is used to feed animals.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation,

grain accounts for 13% of cattle dry feed. In 2021 China imported 28m tonnes of corn to feed its pigs, more than Ukraine exports

in a year.

Working on making a change

Immediate relief would come from breaking the Black Sea

blockade. Roughly 25m tonnes of corn and wheat,

equivalent to the annual consumption of all of the world’s least developed

economies, is trapped in Ukraine. Three countries must be brought onside:

Russia needs to allow Ukrainian shipping; Ukraine has to de-mine the approach

to Odesa, and Turkey needs to let naval escorts through the Bosporus.

That will not be easy. Russia, struggling on the battlefield, is trying

to strangle Ukraine’s economy. Ukraine is reluctant to clear its mines.

Persuading them to relent will be a task for countries, including India and

China, that have sat out the war. Convoys may require armed escorts endorsed by

a broad coalition. Feeding a fragile world is everyone’s business.

The White House is working to put advanced anti-ship missiles in the

hands of Ukrainian fighters to help defeat Russia’s naval blockade, officials

said, amid concerns, that more powerful weapons that could sink Russian

warships would intensify the conflict.

But several issues are keeping Ukraine from receiving the missiles. For

one, there is limited availability of platforms to launch Harpoons from shore

-- a technically challenging solution according to several officials -- as it

is primarily a sea-based missile.

Two US officials said the United States was working on potential

solutions to pull a launcher off a US ship. According to experts and industry

executives, both missiles cost about $1.5 million per round.

Bryan Clark, a naval expert at the Hudson Institute, said 12 to 24

anti-ship missiles like the Harpoon with ranges over 100 km would be enough to

threaten Russian ships and could convince Moscow to lift the blockade. “If

Putin persists, Ukraine could take out the largest Russian ships since

they have nowhere to hide in the Black Sea,” Clark said.

Serhii Dvornyk, a member of Ukraine’s mission to the UN, backed

Blinken’s claim and called on Russia to stop “stealing” Ukrainian grain and

unblock the ports, noting that 400 million people around the world depended on

grain from Ukraine. The country’s grain exports fell from 5m tons a month

before Russia’s February invasion to 200,000 tons in March and about 1.1m tons

in April, he added.

Today also, the

European Commission published a

decision to gather

monthly data on levels of stocks in the EU of cereals, oilseeds, and rice. This

is a direct follow-up of the Communication

on “safeguarding food security and reinforcing the resilience of food systems” presented on 23 March. The aim is to better

monitor stock levels in the current environment of high prices and perceived

uncertainty about supplies.

For updates click hompage here