By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

On Jan. 16, the

Chinese Ministry of Water Resources announced that Beijing invested more than 1

trillion yuan ($148 billion) on water resource management in 2022, a whopping

44 percent increase from the previous year. Elsewhere, Pakistan suggested

that water resource

management projects need to become a priority for the China-Pakistan Economic

Corridor because by

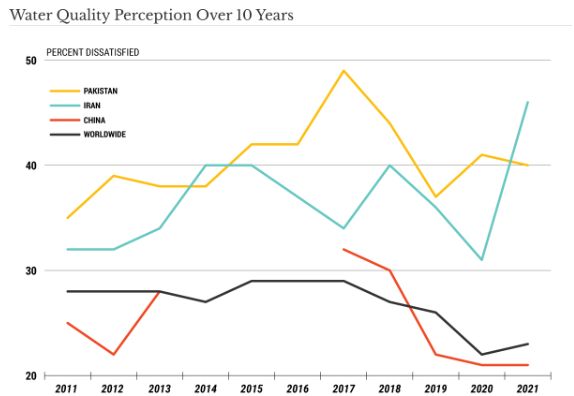

2025, Pakistan is expected to be a water-scarce country. Weeks earlier, an

Iranian official confirmed that 270 cities and towns suffered from acute water

shortage as water levels at dams dropped to critically low levels.

Factories in

southwest China had to suspend their work last summer after a record-breaking

drought caused some rivers in the country – including parts of the Yangtze – to

dry up. Hydropower and shipping were also affected; Sichuan province was deemed

a “grave situation” because it generates more than 80 percent of its energy

from hydropower.

Pakistan is in a

similar situation. The Indus River is a source of more than 17 gigawatts of

hydropower. It provides water to the Indus basin irrigation system, supporting

over 90 percent of the country’s agricultural output. Poor water management,

rapid population growth, drought, and floods have created a truly dire

situation.

In Iran, a semi-arid

climate and declining precipitation over the past decade have played their part

in the crisis. Still, perennial inefficient water management since the 1990s is

the larger problem. After the 1979 revolution, the new regime advanced a policy

of national food self-sufficiency, which involved producing enough staple crops

to meet the country’s needs instead of relying on imports. To that end,

agricultural production became reliant on groundwater extraction, and

slow-filling aquifers have been unable to keep up with the growing number of

water users and withdrawals.

These issues may not

be new, but they are all getting worse. And the fact that these three countries

are geographically interconnected has been a wake-up call for other nations

worldwide that have dealt with, or are soon to deal with, similar water

shortages and their associated consequences.

Indeed, water is so

fundamental to geopolitics that it is often overlooked. Water supplies play

critical roles in sustaining life, agriculture, and industry. The supply levels

themselves can fluctuate dramatically for reasons outside of a government’s

control. However, given the increasing threat of water shortages and the

consequences, governments are increasingly more aggressive in taking what

action they can to ensure supply.

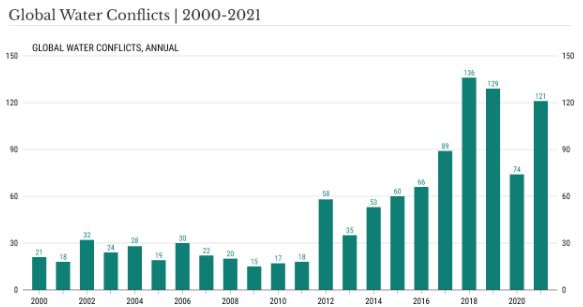

Disputes over control of water resources historically

end in violence. The historical dispute between Ethiopia and Egypt over water

from the Nile River is the one that has garnered the most attention. Even

today, the water supply in Donbas is carefully managed on both sides. In

Kherson, understanding how water supplies to Crimea could be cut was key to understanding

the fighting on the ground. More, the Russian attack on the Dnipro hydropower

plant was meant to sever electricity to the region as part of the Russian

strategy to down Ukraine's critical infrastructure. In war, water is at once a

weapon and a casualty.

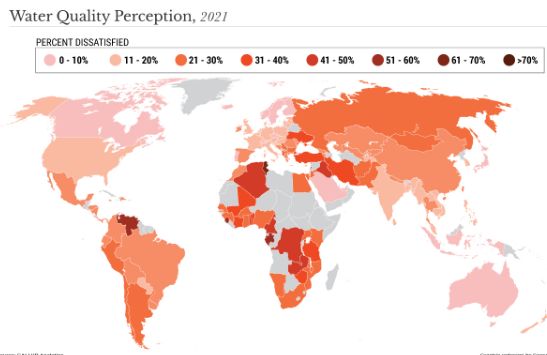

But water is only

part of the equation. The droughts of 2022, followed by the warmest winter in

years in the Northern Hemisphere, have many governments on edge this year as

the downstream effects of water shortage take shape. The potential food crisis,

initially the result of last year’s energy crisis, may only worsen. The impact

will be felt the most in places like Africa and the Middle East, where water

scarcity is a constant concern. Refugee flows from Iraq, Syria, and Yemen may

increase. Food insecurity will likely grow in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia.

And because it’s unclear how much food will be available for export from

otherwise large producers such as Russia and Ukraine in 2023, countries with

limited domestic production have even more reason for concern, especially as

their citizens grow more restive.

But even for major powers like China, Pakistan, and

Iran, things will likely get worse before they get better. All three are

already dealing with socioeconomic distress. It’s unknown how much the COVID-19

pandemic hurt the Chinese economy, but it isn’t good, with reports painting a

particularly bleak picture of youth unemployment. (That is to say, nothing of

China's economic problems, independent of the pandemic.) Pakistan is

seeing its worst

socio-political crisis in years. Iran has been embroiled in high-profile

protests for some time.

Inflation is high in all three countries, as is economic unrest from class

inequality. Adding water stress could make things even more explosive.

Further instability in any of the three major players

will likely have a spillover effect in the Middle East and beyond. A troubled

Pakistan and Iran simultaneously will make Turkey and Saudi Arabia nervous. And

what happens in China – one of the world’s largest consumers of resources and

one of its biggest economic engines – matters to the rest of the world. Factory

shutdowns due to water shortages in post-pandemic China would trigger new

supply chain shocks affecting Europe and the U.S. Neither is decoupled enough

from the Chinese powerhouse to ignore such shocks.

Both have their water

issues to deal with. Lower levels in the Rhine triggered alarms for European

inland shipping last year; further reductions will likely hamper economic

activity in Western Europe. Last year, water scarcity compelled the U.S.

government to limit water releases in western states. If things get worse, U.S.

policymakers will be forced to choose between water releases, electricity

generation, and industrial and food production on the one hand and water

conservation on the other.

Water is finite, so

it’s clear that concerns over its use and distribution will increase as

reserves dwindle. Under higher pressure from citizens, governments will search

for quick fixes. If a fix for one country comes at the expense of another,

tensions will inevitably arise – perhaps violently. Each government will manage

or try to manage the situation differently. In poorer countries, militias may

continue to fight over water. In contrast, new policies over water usage and

likely new technologies for keeping and improving water infrastructure will be

debated in wealthier nations. Water stress highlights another socio-economic

challenge the world must tackle before it worsens.

For updates click hompage here