By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

What To Expect In 2023

The world is constantly changing, but some changes are

more critical than others. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will likely be

remembered as the start of a new era in geoeconomics. In response to the war,

the West launched sanctions against Russia, escalating the economic war the

Kremlin began when it blocked Ukraine from trading with the world through its

ports. Moscow answered by drastically reducing natural gas exports to Europe.

The uncertainty and tit-for-tat measures kicked off an energy crisis. And the

war renewed focus on the growing divide between the West and a nascent

revisionist bloc led by China and Russia. It isn't easy to see a path back to

the status quo ante Bellum, but several significant trends that will define the

next decade have become clear.

Protectionism And Global Realignment

For years before

COVID-19, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea challenged the economic,

financial, security, and geopolitical order the United States and its allies

created after World War II. The era of relentless globalization had started to

slow or even reverse. The pandemic kicked things into overdrive, accelerating

reshoring and so-called friend sharing and depriving developing economies of

foreign investment.

The war in Ukraine

and its economic aftereffects are squeezing developing countries even more. In

2022, most of them put off making a choice between the West and Russia, hoping

for a resolution to the conflict that would ease their economic pain. A case in

point is Hungary, which, like many of these countries, depends on Russian

energy and other commodities to sustain its economy and thus is wary of

breaking ties with Moscow. Budapest has sought to slow the progression of

Western sanctions against Russia. Others have avoided adopting anti-Russia

sanctions altogether.

For Europe, the

conflict between Russia and the West has shaken public and corporate confidence

about the near future and made it nearly impossible to do business with Russian

entities. Elsewhere, companies expend time and resources checking whether their

operations will incur sanctions, looking for alternatives whenever possible.

The Black Sea is a de facto war zone, with the upside of encouraging investment

in overland infrastructure and the downside of making maritime trade more

expensive.

As crucial as

European developments are, China and its internal stability may be the more

significant economic challenge in 2023. Facing growing protests late in the

year, the Chinese government abandoned its zero-COVID policy with no apparent

plan B. Official data is sparse and unreliable, and local and regional

governments have been put in charge of managing the situation. It is unclear

whether this will become a headache for Chinese leader Xi Jinping, especially

since it falls between the start of the political transition in November and

its end in March when most officials will have their new posts confirmed.

Meanwhile, the United States is escalating its trade war with China.

The result will

likely be a fragile economic recovery for China in 2023. The enduring weakness

of the real estate sector has outweighed positive impulses in other economic

areas, and fear of a financial crisis weighs on private investment. Increasing

youth unemployment adds a dangerous element to the mix. Beijing has taken steps

recently to solve the real estate sector’s liquidity crisis, but it needs

political stability for the measures to be effective.

This is not good news

for the global economy. As much as the West would like to be shielded from

events in China, Europe, and the U.S. still depend on Chinese manufacturing

essential inputs. Chinese lockdowns created kinks in supply chains, and the

country’s political and economic instability could prolong them. Consumption

and industrial activity in the U.S. and Europe are already in retreat, and

there’s no end to the energy crisis. A crisis in China would only make things

worse.

Stagflation And Greenflation

In addition to the

global economic slowdown, for the first time since the 1970s, the world is

simultaneously facing high inflation. The drivers of this bout of inflation

include excessively loose monetary and fiscal policies that were kept in place

for too long, the restructuring of global trade caused by the pandemic, and the

sharp spike in the cost of energy, industrial metals, fertilizers, and food as

a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Angered by the unequal distribution

of the gains of globalization, voters demanded more government support for

workers and those left behind. However well-intentioned, such policies risk an

inflationary spiral as wages and prices struggle to keep pace. Rising

protectionism also restricts trade and impedes the movement of capital,

limiting improvements on the supply side.

To the extent that

the energy crisis is causing high inflation, investment in renewables will

mitigate inflationary pressure. Renewable capacity will take time to develop,

however, and in the meantime, there is underinvestment in fossil fuel capacity.

The latter will take priority. Moreover, the green transition will require the

development of new supply chains for specific metals and will increase energy

costs generally, creating what’s been termed “reinflation.”

This coincides with a

rapidly aging population in developed countries, China, and other emerging

economies. Young people produce more, while older people spend their savings

and consume more services. And due to the market uncertainty caused by the

pandemic and the war in Ukraine, young people are producing less. They are

reluctant to invest, which translates into a general economic slowdown.

Therefore, just as the global economy will continue fragmenting into 2023, so

will inflation persist.

Future Of Tech

The war in Ukraine

has also disrupted the tech industry. While most sectors have been impacted by

declining investment and the challenging state of affairs, tech appears to be

the hardest hit. Twitter, for example, has cut its workforce by 50 percent, and

Facebook's parent company Meta is letting go of 11,000, about 13 percent, of

its employees. Amazon reportedly cut 10,000 jobs, representing about 1 percent

of its global workforce. Meanwhile, FTX, the second-largest cryptocurrency

exchange in the world, recently valued at $32 billion, has imploded. The full

fallout of its collapse is still unclear, but other crypto firms have already

felt the effects.

Gone are the days of

the early 2000s, when global markets were relatively stable, and supply chains

built on cheap labor were reliable. In those times, companies increasingly

depended on the internet to grow their business, and tech firms benefited from

low-interest rates. But the factors that helped propel the fast growth of the

early 2000s are today progressively volatile as the global economy hobbles

through the early stages of restructuring.

Like companies in

other sectors, many tech businesses won’t recover, while others will adapt and

bounce back slowly. New opportunities will arise. The restructuring of

manufacturing and supply chains will require technology, and automation will

increase, especially as the population ages. More critically, governments will

likely seize the opportunity to steer the tech industry in specific directions.

There has been much talk about social media's role in politics and shaping

policy. As a result, lawmakers have tried to regulate privacy and competition

related to social media platforms. Cybersecurity is also an increasingly

concerning issue for governments worldwide and will likely continue as the

sophistication of cyberattacks increases. Governments will therefore be pushed

to become more assertive in regulating tech beyond its military applications.

Geoeconomics For 2023

The major trends in

geoeconomics for 2023 and beyond are interconnected. The challenges they pose

will require a systematic, coherent approach, but the political leadership in countries

worldwide needs help to keep up. The speed of the change requires a different

toolset than governments are used to, leaving them trying, and sometimes

failing, to adapt to new realities. Cooperation is increasingly difficult, but

it has grown stronger in some limited areas, like the West’s economic war

against Russia following the Ukraine invasion.

Thus, even as deglobalization gains momentum,

interdependency isn’t going away. Restructuring itself will be a global

process. There’s no avoiding that the world today is interconnected in ways

never seen before. Different perspectives will need to be reconciled, and

people’s place in society beyond their economic value as consumers and

political value as voters will have to be acknowledged. Human behavior, and

therefore state behavior, is driven by everything from politics and economics

to culture and psychology and even technology. This complexity will navigate

tomorrow's challenges and potential solutions of tomorrow.

The world is

constantly changing, but some changes are more critical than others. Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine will likely be remembered as the start of a new era in

geoeconomics. In response to the war, the West launched sanctions against

Russia, escalating the economic war the Kremlin began when it blocked Ukraine

from trading with the world through its ports. Moscow answered by drastically

reducing natural gas exports to Europe. The uncertainty and tit-for-tat

measures kicked off an energy crisis. And the war renewed focus on the growing

divide between the West and a nascent revisionist bloc led by China and Russia.

It isn't easy to see a path back to the status quo ante Bellum, but several

significant trends that will define the next decade have become clear.

Protectionism And Global Realignment

For years before

COVID-19, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea challenged the economic,

financial, security, and geopolitical order the United States and its allies

created after World War II. The era of relentless globalization had started to

slow or even reverse. The pandemic kicked things into overdrive, accelerating

reshoring and so-called friend sharing and depriving developing economies of

foreign investment.

The war in Ukraine

and its economic aftereffects are squeezing developing countries even more. In

2022, most of them put off making a choice between the West and Russia, hoping

for a resolution to the conflict that would ease their economic pain. A case in

point is Hungary, which, like many of these countries, depends on Russian

energy and other commodities to sustain its economy and thus is wary of

breaking ties with Moscow. Budapest has sought to slow the progression of

Western sanctions against Russia. Others have avoided adopting anti-Russia sanctions

altogether.

For Europe, the

conflict between Russia and the West has shaken public and corporate confidence

about the near future and made it nearly impossible to do business with Russian

entities. Elsewhere, companies expend time and resources checking whether their

operations will incur sanctions, looking for alternatives whenever possible.

The Black Sea is a de facto war zone, with the upside of encouraging investment

in overland infrastructure and the downside of making maritime trade more expensive.

As crucial as

European developments are, China and its internal stability may be the more

significant economic challenge in 2023. Facing growing protests late in the

year, the Chinese government abandoned its zero-COVID policy with no apparent

plan B. Official data is sparse and unreliable, and local and regional

governments have been put in charge of managing the situation. It is unclear

whether this will become a headache for Chinese leader Xi Jinping, especially

since it falls between the start of the political transition in November and

its end in March when most officials will have their new posts confirmed.

Meanwhile, the United States is escalating its trade war with China.

The result will

likely be a fragile economic recovery for China in 2023. The enduring weakness

of the real estate sector has outweighed positive impulses in other economic

areas, and fear of a financial crisis weighs on private investment. Increasing

youth unemployment adds a dangerous element to the mix. Beijing has taken steps

recently to solve the real estate sector’s liquidity crisis, but it needs

political stability for the measures to be effective.

This is not good news

for the global economy. As much as the West would like to be shielded from

events in China, Europe, and the U.S. still depend on Chinese manufacturing

essential inputs. Chinese lockdowns created kinks in supply chains, and the

country’s political and economic instability could prolong them. Consumption

and industrial activity in the U.S. and Europe are already in retreat, and

there’s no end to the energy crisis. A crisis in China would only make things

worse.

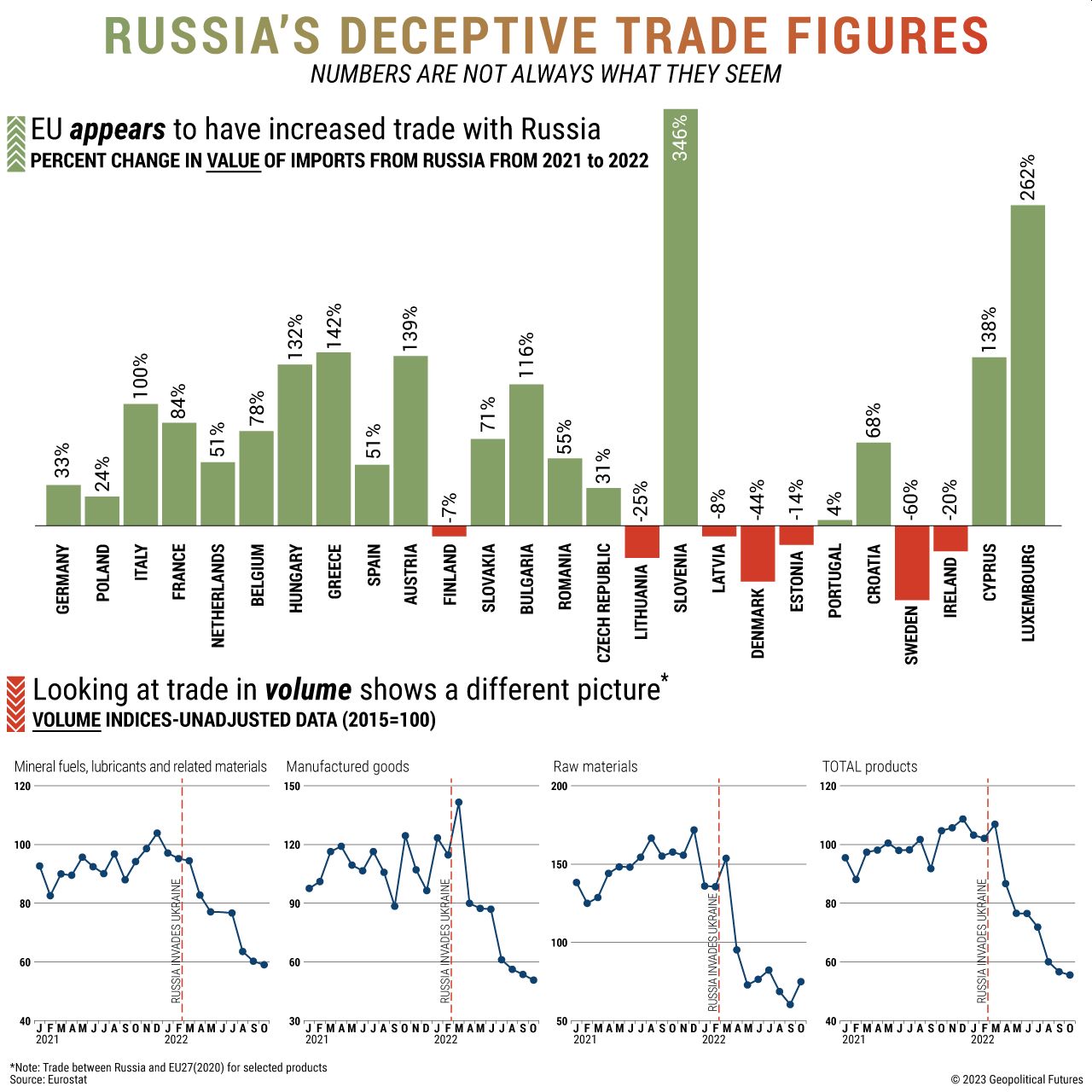

The sanctions imposed

by the West on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine precipitated a shift in

Russia’s trade patterns. The sanctions were meant to cut off economic ties with

Russia in Europe, but a complete severance was nearly impossible. As such, companies

in some sectors continued to do business with Russian firms at reduced levels

and at a more significant expense. The energy sector was hit particularly hard

by the changes. Energy prices soared, which had ripple effects for the rest of

the economy. The spike in the cost of Russian exports – especially oil and

natural gas – meant that the value of these exports to Europe increased. Still,

notably, the volume of Russian deliveries declined.

Notably, the value of

Slovenia’s and Luxembourg’s imports from Russia appears to have increased much

more than that of other European countries. This can be explained by the fact

that Russian exports to Slovenia are mostly energy products, and Russian

exports to Luxembourg are mainly metallurgical products, whose price is highly

dependent on energy costs.

As a result, the

overall value of Russian exports to Europe was higher in 2022 than in 2021,

despite Russia having sold fewer goods and services to European markets last

year. While the volume of exports of Russian raw materials to Europe has

fluctuated, exports in other segments are dropping, marking a shift that will

likely last for months and years to come as Europe finds alternatives.

For updates click hompage here