By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Three Critical Trends To Watch Out For

Last week when we

were looking for the most explosive trends in the world, we first came up with about

fourteen, which included issues like the deadly conflict in Ethiopia, the fight

against terrorism in the Sahel, and many other potential conflicts. But in the

end, I decided to focus on only three, which will include an actual historical

example that tells us about Russia in particular.

1. Russia is

banking on a cold winter, crumbling the resolve of Ukrainians and their allies

across Europe providing military support as Moscow cuts off energy supplies and

targets Ukraine’s entire energy infrastructure to keep the country as cold and

dark as possible. It could provide Russia a respite to regroup its forces

and prepare for spring offensives. It could drive some European countries

grappling with surging energy prices and economic woes to question their support

for Ukraine. But it could also steel Europe’s resolve, harden Ukraine’s

determination, and presage more effective Ukrainian offensives against Russia’s

beleaguered forces when the weather warms up. Most defense analysts we spoke to

agreed that the first few months of 2023 will be crucial to determining the

trajectory of the war in Ukraine and whether Putin’s massive military gambit

will ultimately fail.

2. Russia

is running out of munitions to lob at Ukrainian civilian targets and has turned

to Iran for a steady supply of drones and other sophisticated munitions. The

head of Israel’s top spy organization, David Barnea of Mossad, warned that Iran is secretly planning to “widen and

broaden” its weapons shipments to Russia shortly. Of course, this isn’t an

example of a charitable Iran giving poor Russia some weapons for the holidays

out of the kindness of its own heart. In exchange, Iran could get unprecedented

levels of new military hardware and technical support from Russia, including

Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets, air defense systems, and other advanced

military technology. U.S. officials warn that the new army bromance could

prolong Ukraine's war and threaten U.S. allies and partners in the Middle East.

3. Nonproliferation

games. 2022 was filled with a lot of bad news in the world of nuclear

nonproliferation. 2023 has a similarly depressing forecast but one worth

tracking closely nonetheless. North Korea is preparing its seventh atomic

test, showcasing how it

can expand its nuclear program despite devastating international sanctions and

diplomacy dead in the water. Russia will likely continue rattling the

nuclear saber to erode Europe’s support for Ukraine, even though U.S. officials

deem any tactical atomic weapon use by Russia as highly unlikely. According to

U.N. watchdogs, efforts to revive the Iran nuclear deal have run aground, and

Tehran is already expanding its stockpile of highly enriched uranium.

Meanwhile, China is set to expand its nuclear weapons program, with plans to

increase its supply of 400 nuclear warheads to 1,500 by 2035.

Russian tanks near Ukraine’s eastern border, Rostov

region, Russia, January 2022:

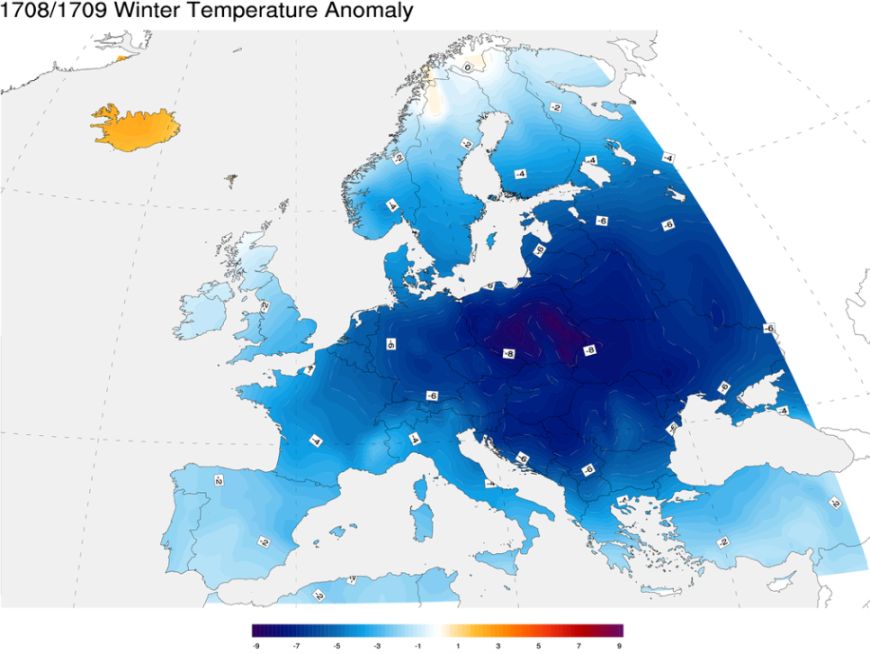

The Russian Cossack War

One of Russia’s most

significant military victories came with the coldest European winter in 500

years. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Tsar Peter the Great

struggled to repel the formidable forces of Charles XII of Sweden, advancing on

Moscow. Then came the Great Frost of 1708–9. Birds were said to have frozen in

midflight and dropped dead to the ground. Charles’s army of more than 40,000

men soon lost half its strength from exposure and starvation. To escape the

cold, the Swedish king led the remnants of his army south into Ukraine to join

the Cossack leader, Hetman Ivan Mazepa, and his

forces. But the damage was done. The following summer, Peter’s Russian army

routed Charles’s weakened troops at the Battle of Poltava, ending Sweden’s

empire and its designs on Russia.

The Swedes were

neither the first nor the last European army to suffer the “General Winter”

ravages on Russia’s frontiers. Exacerbated by the vast expanse of the Eurasian

landmass, winter fighting there has often proved to be the downfall of great

armies. This phenomenon has often worked to Russia’s advantage for centuries,

as a succession of powerful militaries has succumbed to inadequate equipment,

short supply lines, and poor preparation. But as Russian

President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine enters the harshest months

of the year, there are many indications that it may be Russia, rather than its

adversary, that suffers the worst consequences this time.

His Empire For A Horse

Europe’s best-known winter

defeat in Russia came in 1812—just over a century after the Battle of

Poltava—when Napoleon’s Grande Armée retreated from Moscow. Russia’s

scorched-earth tactics, which left the French with no food or shelter along the

withdrawal line, made the effect even more deadly. Yet the most significant

casualties had occurred earlier.

The Grande Armée had

been almost half a million strong when it crossed the River Neman, the frontier

between Prussia and Russia, in June 1812. But it soon lost a third of its strength

from the summer heat, disease, hunger, and exhaustion as the emperor forced his

men toward Moscow. Although the retreat into Russia’s expanse was initially

unintended, Tsar Alexander I’s commanders soon realized the advantage. They

kept withdrawing east and did not make a stand until General Mikhail Kutuzov

was ordered to halt Napoleon at Borodino, 75 miles west of Moscow. The battle

proved a costly victory for the French, even though it enabled them to enter

Moscow unopposed.

But it was the

approaching winter that proved fatal for the invaders. Napoleon wasted five

weeks in Moscow expecting the tsar to come to terms. When the Grande Armée

finally started withdrawing to central Europe on October 19, the soldiers wore

their summer uniforms. They had also lost their baggage trains and could expect

little food along the way. Their most significant deficiency was in the cavalry

to hold off marauding Cossacks. The shaggy Cossack ponies were accustomed to

the winter blizzards, which began a month later, while the last of the chargers

and draft horses from western Europe collapsed from the cold and lack of

forage. Starving soldiers hacked off their meat even before they were dead.

Desertion or surrender was far from a guarantee of survival. Avenging Cossacks waited

to skewer enemy soldiers on their long lances; Russian peasants slaughtered

them with scythes. By early December, Napoleon feared a coup d’état during his

absence and, abandoning his army, headed for Paris before his frozen men could

reach safety. By this point, his forces had suffered nearly 400,000 casualties,

and he had lost his reputation for invincibility on the battlefield.

Charles XII of Sweden and Hetman Ivan Mazepa

The way Russia won

was less well-known, although perhaps equally significant. Despite losing

200,000 of its men, Russia’s military leadership was far less concerned about

casualties than Napoleon. Russian officers still treated their peasant soldiers

as little better than serfs (and serfdom would not be abolished in Russia for

another 50 years). This lack of interest in soldiers’ well-being—and the casual

attitude to massive losses through so-called meat-grinder tactics—are apparent

in Putin’s army in Ukraine today.

Red Terror, White Frost

Another half-century

later, in World War I, the attitude of Russia’s military authorities had barely

changed. Their men were expendable. Trench life for the rank and file along the

eastern front that ran through Belorussia, Galicia, and Romania from 1915 to

1917 was an inhuman experience. And many resented that officers retired

each night to the warmth and relative comfort of peasant log huts behind the

front.

“Having dug

themselves into the ground,” the Russian writer and anti-tsarist Maxim Gorky

observed of the enlisted men, “they live in rain and snow, in filth, in cramped

conditions; they are being worn out by disease and eaten by vermin; they live

like beasts.” Many lacked boots and had to resort to shoes made from birch

bark. Stations for treating the wounded at the front were almost as primitive

as they had been in the Crimean War. This reality was in cruel contrast to the

photographs of the tsarina and her grand duchess daughters immaculately

dressed as nurses before the February 1917 revolution.

Winter conditions in the

Russian Civil War (1917–21) were even worse.

The most pitiful victims were the civilian refugees fleeing the Bolshevik

onslaught, or what became known as the Red Terror. During the winter of 1919,

the collapse of Admiral Kolchak’s White Russian armies in Siberia produced

terrible scenes along the jammed Trans-Siberian Railroad. Aristocrats,

middle-class families, and anti-Bolsheviks of all backgrounds were trying to

escape to Vladivostok in the Russian Far East to avoid capture by the Communist

Red Army, advancing from the Urals.

By mid-December of

that year, the Reds caught up with the tail of the line. They took the southern

Siberian city and industrial hub of Novo-Nikolaevsk

(present-day Novosibirsk), along with numerous trains still blocked there. The

city itself was in the grip of a typhus epidemic. All horses, carts, and sleds

available had already been taken, so the desperate set out on foot, not knowing

that farther ahead in Krasnoyarsk, cases had reached more than 30,000.

“A mass retreat is one

of the saddest and most despairing sights in the world,” Captain Brian Horrocks, a British officer in the Allied intervention in

Russia, wrote. “The sick just fell and died in the snow.” He was

horrified by the squalid condition even of those refugees who had managed to

find a place in packed cattle wagons. Most wagons lacked heating as

temperatures dropped below minus 30 degrees Celsius. “The thing which impressed

me most was the fortitude with which the women, many of them reared in luxury,

were facing their hopeless future,” he wrote. “The menfolk were much more given

to self-pity.” Kolchak’s staff officers

were, by then, drinking themselves into oblivion.

As White Russian,

Czech, and Polish commanders argued bitterly over priority for their troop

trains, starving and frozen refugees were dying at an alarming rate. One

officer wrote that trains at some Siberian stations were unloading hundreds of

bodies of people who had died from cold and disease. “These bodies were stacked

up at the stations like so much cordwood,” another officer wrote. “Those who

remained alive never talked, never thought of anything save how they might

escape death and get farther and farther away from the Bolsheviks.”

In the northern

Caucasus, known for its blazing summer heat, winter could sometimes produce

drops in temperature of more than 30 degrees Celsius in less than an

hour. In February 1920, General Dmitry Pavlov’s cavalry divisions were

caught in the open by a sudden blizzard. Pavlov “lost half of his horses which

froze in the steppe,” the Red Army high command noted. But the human losses

were far worse. “We left thousands of men frozen to death behind in the steppe,

and the blizzard buried them,” a Cossack officer recounted. Those who survived

did so by huddling against their horses. Pavlov, who had ignored warnings

of the possible change in the weather, suffered severe frostbite.

Stalin’s Icebreakers

By the twentieth

century, winter conditions on the Eurasian landmass posed a growing threat to

humans, horses, and military weaponry. Sometimes this worked to Russia’s

detriment. Despite its disproportionate strength and its massive expenditure of

ammunition, the Soviet army failed to break Finnish resistance in the Winter

War of 1939–40, following Stalin’s invasion of Finland. The Finns, proving

themselves even better practitioners of winter tactics than their invaders,

terrorized Red Army soldiers daily and night as their white-camouflaged ski

troops launched surprise attacks from forests, then disappeared like ghosts.

Their bravery and skill persuaded Stalin to accept Finland’s independence. But

it also served as a lesson for the war to come.

During the rapid

military mechanization between the two world wars, the Soviet Union created the

largest tank force in the world. The Red Army at least learned that guns and

engines needed special lubricants in extreme conditions. Such measures proved

key in Stalin’s ability to block Hitler’s armies in front of Moscow in December

1941. Both the German army and the Luftwaffe were unprepared. They had to light

fires under their vehicles and aircraft engines to defrost them.

German soldiers

referred bitterly to winter conditions as “weather for Russians.” They

envied the Red Army’s winter uniforms, with white camouflage suits and

padded cotton jackets, which were far more effective than German greatcoats.

Russian military historians have attributed the comparatively low rate of

frostbite and trench foot among Soviet forces to their old military practice of

using layered linen foot bandages instead of socks. German soldiers also

suffered more rapidly because their jackboots had steel studs that drained any

warmth. In February 1943, when the remnants of Field Marshal Paulus’s Sixth

Army finally surrendered at Stalingrad—the psychological turning point of World

War II—more than 90,000 German prisoners limped out of the city on

frost-ravaged feet. Yet their suffering had been caused less by cold than by

Hitler’s orders to hold on there and German panzers' inability to counterattack

in the snow with their narrow tracks.

General Winter also

played a significant role in the Red Army’s final victory in 1945. The

tremendous Soviet breakthrough in January, a charge from the River Vistula to

the River Oder, depended on the weather. Russian forecasters had predicted, “a

strange winter,” with “heavy rain and wet snow” after the hard frosts of

January. An order went out to repair boots. Stalin and the Red Army’s supreme

command set January 12 as the start date for the offensive, so the Soviets’

tank armies could take advantage of the deep-frozen ground before any thaw set

in. Characteristically, Stalin falsely claimed that he had advanced the date

from January 20 to take pressure off the Americans in the Ardennes. (U.S. forces

had already halted the German offensive there just after Christmas.) There was

another motive: Stalin wanted to control the bulk of Polish territory before

meeting U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston

Churchill at Yalta in February.

Stalin’s commanders

did not let him down. “Our tanks move faster than the trains to Berlin,”

boasted the ebullient Colonel Iosif Gusakovsky. He had not bothered to wait for bridging

equipment to reach the frontlines before attempting to cross the River Pilica. He ordered his leading tanks to smash the ice with

gunfire and drive straight across the riverbed. The tanks, acting like

icebreakers, pushed the ice aside “with a terrible thundering noise,” a

terrifying experience for the poor drivers. The German eastern front in Poland

collapsed under the armored onslaught again because the Soviet T-34’s broad

tracks could cope with the ice and snow far better than any German panzer.

After 1945, the Red

Army’s achievements in winter warfare gave it a fearsome reputation in the

West. It was not until the Soviet Union’s ill-planned invasion of

Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1968—the Warsaw Pact forces lacked maps, food

supplies, and fuel—that Western analysts began to suspect they might have

overestimated the Soviets’ warfighting abilities.

Finally, in the

1980s, the collapse of the Soviet empire was marked by its doomed struggle to

control Afghanistan, a terrain that made winter warfare impossible for

conventional armies. Then, during the economic collapse in the 1990s, Russian

President Boris Yeltsin’s government often proved unable to pay officers and

soldiers alike, and corruption became institutionalized. Conscripts were

frequently on the edge of starvation because their rations were sold off;

theft, bullying, and ill-discipline became rampant. Spare parts from vehicles

and anything from fuel to light bulbs, boots, and especially any cold weather

kit disappeared onto the black market.

Corruption became

even worse following Russia’s chaotic invasion of Georgia in 2008. Putin began

throwing money at the armed forces. The waste on prestige projects encouraged

contractors and generals alike to pad their bank accounts. Little appears to

have been done to reassess military doctrine. The Russian idea of urban warfare

had still not evolved from World War II, with their artillery, the “god of

war,” smashing everything to rubble. This approach would continue during

Russian intervention in the Syrian civil war in 2015.

Yet Putin’s greatest

triumph in Russian eyes was the covert seizure of Crimea the year

before by infiltrating it with un-uniformed “little green men” from special

forces. This was part of Putin’s angry reaction to

the Maidan revolution in Kyiv, which forced his ally, President Viktor

Yanukovych, to flee and led to the start of

fighting in the Donbas region of Russian-speaking eastern Ukraine.

Putin In Denial

In February 2022,

eight years later, Putin launched his “special military

operation” in Ukraine. At the time, the vanguard was told to bring

their parade uniforms ready to celebrate victory—one of the most outstanding

examples of military hubris in history. Yet seven disastrous months later, when

the Kremlin was finally forced to order a “partial mobilization” of the Russian

population, it had to warn those called up that uniforms and equipment were in

short supply. They would have to provide their body armor and even ask their

mothers and girlfriends for sanitary pads instead of field dressings. The lack

of bandages is astonishing, especially as winter intensifies, since they are

vital to keeping frost from entering open wounds. Adding to the dangers are

mortar rounds hitting the frozen ground: unlike soft mud, which absorbs most of

the blast, frozen ground sometimes causes fragments to ricochet in brutal ways.

Putin’s new commander

in chief in the south, General Sergei Surovikin,

is determined to clamp down on attempts by some conscripts to avoid combat.

Many have been resorting to the sabotage of fuel, weapons, and vehicles, to say

nothing of self-inflicted wounds and desertion. Yet the Russian army’s

long-standing structural problem—its shortage of

experienced noncommissioned officers—has also led to a terrible record of

maintaining weapons, equipment, and vehicles. With sensitive technology such as

drones, these

problems will become especially costly in winter.

As both sides enter a

far more challenging season of fighting, the outcome will largely depend on

morale and determination. While Russian troops curse their shortages and lack

of hot food, Ukrainian troops now benefit from insulated camouflage suits,

tents with stoves, and sleeping bags provided by Canada and the Nordic nations.

Putin seems to be in denial about the state of his army and the way that

General Winter will favor his opponents. He may also have made another mistake

by concentrating his missiles against Ukraine’s energy network and vulnerable

civilian population. They will endure the most significant suffering, but there

is little chance they will break.

For updates click hompage here