By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

In March, at the end

of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow, Russian President Vladimir

Putin stood at the door of the Kremlin to bid his friend farewell. Xi told his

Russian counterpart, “Right now, there are changes—the likes of which we

haven’t seen for 100 years—and we are driving these changes together.” Putin,

smiling, responded, “I agree.”

The tone was

informal, but this was hardly an impromptu exchange:

“Changes unseen in a century” has

become one of Xi’s favorite slogans since he coined it in December 2017. Although

it might seem generic, it neatly encapsulates contemporary Chinese thinking

about the emerging global order—or disorder. As China’s power has grown,

Western policymakers and analysts have tried to determine what kind of

world China wants and what kind of global order Beijing aims to build

with its power. But it is becoming clear that rather than trying to

comprehensively revise the existing order or replace it with something else,

Chinese strategists have set about making the best of the world as it is—or as

it soon will be.

While most Western

leaders and policymakers try to preserve the existing rules-based international

order, perhaps updating key features and incorporating additional actors,

Chinese strategists increasingly define their goal as survival in a world

without order. The Chinese leadership, Xi Down, believes that the global

architecture erected in the aftermath of World War II is becoming

irrelevant and that attempts to preserve it are futile. Instead of seeking to

save the system, Beijing is preparing for its failure.

Although China and

the United States agree that the post–Cold War order is over, they are betting

on very different successors. In Washington, the return of great-power

competition is thought to require revamping the alliances and institutions at

the heart of the post–World War II order that helped the United States win

the Cold War against the Soviet Union. This updated global order is

meant to incorporate much of the world, leaving China and several of its most

important partners—including Iran, North Korea, and Russia—isolated outside.

But Beijing is

confident that Washington’s efforts will prove futile. In the eyes of Chinese

strategists, other countries’ search for sovereignty and identity is

incompatible with the formation of Cold War–style blocs and will instead result

in a more fragmented, multipolar world in which China can take its place as a

great power.

Ultimately, Beijing’s

understanding may well be more accurate than Washington’s more closely attuned

to the aspirations of the world’s most populous countries. The U.S. strategy

won’t work if it amounts to little more than a futile quest to update a

vanishing order driven by a nostalgic desire for the symmetry and stability of

a bygone era. China, by contrast, is readying itself for a world defined by

disorder, asymmetry, and fragmentation—a world that, in many ways, has already

arrived.

Survivor: Beijing

The very different

responses of China and the United States to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

revealed the divergence between Beijing’s and Washington’s thinking. In

Washington, the dominant view is that Russia’s actions challenge the

rules-based order, which must be strengthened in response. In Beijing, the

prevailing opinion is that the conflict shows the world is entering a period of

disorder, which countries must take steps to withstand.

The Chinese

perspective is shared by many countries, especially in the global South,

where Western claims to be upholding a rules-based order lack credibility. It

is not simply that many governments had no say in creating these rules and

therefore see them as illegitimate. The problem is more profound: these

countries also believe that the West had applied its norms selectively and

revised them frequently to suit its interests or, as the United States did when

it invaded Iraq in 2003, ignored them. For many outside the West, the talk of a

rules-based order has long been a fig leaf for Western power. It is only

natural, these critics maintain, that now that Western influence is declining,

this order should be revised to empower other countries.

Hence Xi’s claim that

“changes unseen in a century” are coming to pass. This observation is one of

the guiding principles of “Xi Jinping Thought,” which has become China’s

official ideology. Xi sees these changes as part of an irreversible trend

toward multipolarity as the East rises and the West declines, accelerated by

technology and demographic shifts. Xi’s core insight is that the world is

increasingly defined by disorder rather than order, a situation that, in his

view, harks back to the nineteenth century, another era characterized by global

instability and existential threats to China. In the decades after China’s

defeat by Western powers in the First Opium War in 1839, Chinese thinkers,

including the diplomat Li Hongzhang—sometimes

referred to as “China’s Bismarck”—wrote of “great changes unseen in over 3,000

years.” These thinkers observed with concern the technological and geopolitical

superiority of their foreign adversaries, which inaugurated what China now

considers a century of humiliation. Today, Xi sees the roles as reversed. The

West now finds itself on the wrong side of fateful changes, and China has the

chance to emerge as a strong and stable power.

Xi at the China–Central Asia summit in Xi'an, China,

May 2023

Other ideas with

roots in the nineteenth century have also experienced a renaissance in

contemporary China, among them social Darwinism, which applied Charles Darwin’s

concept of “the survival of the fittest” to human societies and international

relations. 2021, for instance, the Research Center for a Holistic View of

National Security, a government-backed body linked to the Chinese security

ministry, published National Security in the Rise and Fall of Great

Powers, edited by the economist Yuncheng Zhang. The book, part of a series explaining

the new national security law, claims that the state is like a biological

organism that must evolve or die—and that China’s challenge is survival. And

this line of thinking has taken hold. One Chinese academic told me that

geopolitics today is a “struggle for survival” between fragile and

inward-looking superpowers—a far cry from the expansive and transformative

visions of the Cold War superpowers. Xi has adopted this framework, and Chinese

government statements are full of references to “struggle,” an idea that is

found in communist rhetoric but also in social Darwinist writings.

This notion of

survival in a dangerous world necessitates developing what Xi describes

as “a holistic approach to national security.” In contrast to the

traditional concept of “military security,” which was limited to countering

threats from land, air, sea, and space, the holistic approach to security aims

to oppose all technical, cultural, or biological challenges. In an age of

sanctions, economic decoupling, and cyber threats, Xi believes that everything

can be weaponized. As a result, security cannot be guaranteed by alliances or

multilateral institutions. Countries must therefore do all that they can to

safeguard their people. To that end, in 2021, the Chinese government backed the

creation of a new research center dedicated to this holistic approach, tasking

it with considering all aspects of China’s security strategy. Under Xi, the

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is increasingly conceived of as a shield against

chaos.

Clashing Visions

Chinese leaders see

the United States as the principal threat to their survival and have

developed a hypothesis to explain their adversary’s actions. Beijing believes

that Washington is responding to domestic polarization and its loss of global

power by ramping up its competition with China. According to this thinking,

U.S. leaders have decided that it is only a matter of time before China becomes

more powerful than the United States, so Washington is trying to pit Beijing

against the entire democratic world. Chinese intellectuals, therefore, speak of

a U.S. shift from engagement and partial containment to “total competition,”

spanning politics, economics, security, ideology, and global influence.

Chinese strategists

have watched the United States try to use the war in Ukraine to cement the

divide between democracies and autocracies. Washington has rallied its partners

in the G-7 and NATO, invited East Asian allies to join the NATO meeting in

Madrid, and forged new security partnerships, including AUKUS, a trilateral

pact among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and the Quad

(Quadrilateral Security Dialogue), which aligns Australia, India, and Japan

with the United States. Beijing is particularly concerned that Washington’s

engagement in Ukraine will make it more assertive on Taiwan. One scholar said

he feared that Washington is gradually trading its “one China” policy—under

which the United States agrees to regard the People’s Republic of China as the

only legal government of Taiwan and the mainland—for a new approach that one

Chinese interlocutor called “one China and one Taiwan.” This new kind of

institutionalization of ties between the United States and its partners,

implicitly or explicitly aimed at containing Beijing, is seen in China as a new

U.S. attempt at alliance building that brings Atlantic and European partners

into the Indo-Pacific. It is, Chinese analysts believe, yet another instance of

the United States’ mistaken belief that the world is once more dividing itself

into blocs.

With only North Korea

as a formal ally, China cannot win a battle of alliances. Instead, it has

sought to make a virtue of its relative isolation and tap into a growing global

trend toward nonalignment among middle powers and emerging economies. Although

Western governments take pride in the fact that 141 countries have supported UN

resolutions condemning the war in Ukraine, Chinese foreign policy thinkers,

including the international relations professor and media commentator Chu Shulong, argue that the number of countries enforcing

sanctions against Russia is a better indication of the power of the West. By

that metric, he calculates that the Western bloc contains only 33 countries,

with 167 countries refusing to join in the attempt to isolate Russia. Many of

these states had bad memories of the Cold War when competing superpowers

squeezed their sovereignty. One prominent Chinese foreign policy strategist

explained, “The United States isn’t declining, but it is only good at talking

to Western countries. The big difference between now and the Cold War is that

[then] the West was very effective at mobilizing developing countries against

[the Soviet Union] in the Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia, and

Africa.”

To capitalize on

waning U.S. influence in these regions, China has sought to demonstrate its

support for countries in the global South. In contrast to Washington, which

Beijing sees as bullying countries into picking sides, China’s outreach to the

developing world has prioritized investments in infrastructure. It has done so

through international initiatives, some of which are already partially

developed. These include the Belt and Road and Global Development Initiative,

which invest billions of dollars of state and private-sector money in other

countries’ infrastructure and development. Others are new, including the Global

Security Initiative, which Xi launched in 2022 to challenge U.S. dominance.

Beijing is also working to expand the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a

security, defense, and economic group that brings together major players in

Eurasia, including India, Pakistan, and Russia, and is admitting Iran.

Stuck In The Past?

China is confident

that the United States is mistaken in its assumption that a new cold war has

broken out. Accordingly, it is seeking to move beyond Cold War–style divides.

As Wang Honggang, a senior official at a think tank

affiliated with China’s Ministry of State Security, put it, the world is moving

away from “a center-periphery structure for the global economy and security and

towards a period of polycentric competition and co-operation.” Wang and

like-minded scholars do not deny that China is also trying to become a center

of its own. Still, they argue that because the world is emerging from Western

hegemony, establishing a new Chinese center will lead to a greater pluralism of

ideas rather than a Chinese world order. Many Chinese thinkers link this belief

with the promise of a future of “multiple modernity.” This attempt to create an

alternative theory of modernity, in contrast to the post–Cold War formulation

of liberal democracy and free markets as the epitome of modern development, is

at the core of Xi’s Global Civilization Initiative. This high-profile project

is intended to signal that unlike the United States and European countries, which lecture others on subjects

such as climate change and LGBTQ rights, China respects the

sovereignty and civilization of other powers.

For many decades,

China’s engagement with the world was largely economic. Today, China’s

diplomacy goes well beyond matters of trade and development. One of the most

dramatic and instructive examples of this shift is China’s growing role in the

Middle East and North Africa. The United States formerly dominated this region,

but as Washington has stepped back, Beijing has moved in. China launched a

major diplomatic coup in March by brokering a truce between Iran and Saudi

Arabia. Whereas Chinese involvement in the region was once limited to its

status as a consumer of hydrocarbons and an economic partner, Beijing is now a

peacemaker busily engaged in building diplomatic and even military

relationships with key players. Some Chinese scholars regard the Middle East

today as “a laboratory for a post-American world.” In other words, they believe

that the region is what the entire world will look like in the next few

decades: a place where, as the United States declines, other global powers,

such as China, India, and Russia, compete for influence, and middle management,

such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, flex their muscles.

Many in the West

doubt China’s ability to achieve this goal, mainly because Beijing has

struggled to win over potential collaborators. In East Asia, South Korea is

moving closer to the United States; in Southeast Asia, the Philippines is

developing closer relations with Washington to protect itself from Beijing; and

there has been an anti-Chinese backlash in many African countries, where

complaints about Beijing’s colonial behavior are rife. Although some countries,

including Saudi Arabia, want to strengthen their ties with China, they are

motivated at least in part by a desire for the United States to reengage with

them. But these examples should not mask the broader trend: Beijing is becoming

more active and steadily more ambitious.

Spare Wheels And Body Locks

Economic competition

between China and the United States is also increasing. Many Chinese thinkers

predicted that the election of U.S. President Joe Biden in 2020 would

lead to improved relations with Beijing. Still, they have been disappointed: the

Biden administration has been much more aggressive toward China than expected.

One senior Chinese economist likened Biden’s pressure campaign against the

Chinese technology sector, which includes sanctions on Chinese technology

companies and chip-making firms, to U.S. President Donald Trump’s actions

against Iran. Many Chinese commentators have argued that Biden’s desire to

freeze Beijing’s technological development to preserve the United States’ edge

is no different than Trump’s efforts to stop Tehran’s development of nuclear

weapons. A consensus has formed in Beijing that Washington’s goal is not to

make China play by the rules but to stop China from growing.

This is incorrect:

Washington and the European Union have clarified that they do not

intend to shut China out of the global economy. Nor do they want to decouple

their economies from China’s entirely. Instead, they seek to ensure that their

businesses do not share sensitive technologies with Beijing and to reduce their

reliance on Chinese imports in critical sectors, including telecommunications,

infrastructure, and raw materials. Thus, Western governments increasingly talk

of “reshoring” and “friend shoring” production in such industries or at least

diversifying supply chains by encouraging companies to base production in

countries such as Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, and Thailand.

Xi’s response has

been what he calls “dual circulation.” Instead of considering China as having a

single economy linked to the world through trade and investment, Beijing has

pioneered the idea of a bifurcated economy. One-half of the economy—driven by

domestic demand, capital, and ideas—is about “internal circulation,” making

China more self-reliant regarding consumption, technology, and regulations. The

other half—“external circulation”—is about China’s selective contacts with the

rest of the world. Simultaneously, even as it decreases its dependence on

others, Beijing wants to boost the dependence of other players on China to use

these links to increase its power and exert pressure. These ideas have the

potential to reshape the global economy.

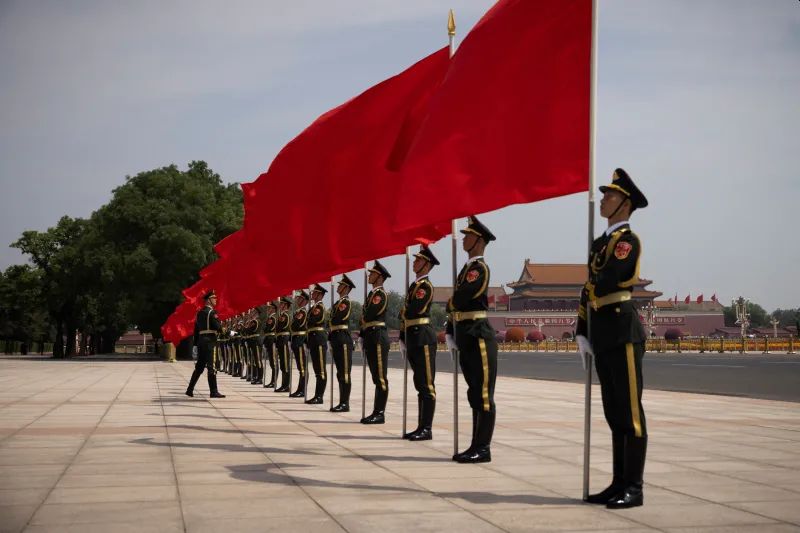

Chinese honor guards, Beijing, May 2023

The influential

Chinese economist Yu Yongding has explained the

notion of dual circulation with two new concepts: “the spare wheel” and “the

body lock.” Following the “spare wheel” concept, China should have alternatives

if it loses access to natural resources, components, and critical technologies.

This idea has come in response to the increasing use of Western sanctions,

which Beijing has watched with concern. The Chinese government is now working

to shield itself from any attempts to cut it off in case of a conflict by

making enormous investments in critical technologies, including artificial

intelligence and semiconductors. But Beijing is also attempting to exploit the

new reality to reduce the global economy’s reliance on Western economic demand

and the U.S.-led financial system. At home, the CCP is promoting a shift from

export-led growth to growth driven by domestic demand; elsewhere, it is

promoting the yuan as an alternative to the dollar. Accordingly, the Russians

are increasing their yuan reserve holdings, and Moscow no longer uses the

dollar when trading with China. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization has

recently agreed to use national currencies, rather than just the dollar, for

trade among its member states. Although these developments are limited, Chinese

leaders are hopeful that the weaponization of the U.S. financial system and the

massive sanctions against Russia will lead to further disorder and

increase other countries’ willingness to hedge against the dollar’s dominance.

The “body lock” is a

wrestling metaphor. It means that Beijing should make Western companies reliant

on China, making decoupling more difficult. That is why it works to bind as

many countries as possible to Chinese systems, norms, and standards. In the

past, the West struggled to make China accept its rules. Now, China is

determined to make others bow to its norms, and it has invested heavily in

boosting its voice in various international standard-setting bodies. Beijing is

also using its Global Development and Belt and Road Initiatives to export its

model of subsidized state capitalism and Chinese standards to as many countries

as possible. Whereas China’s objective was once integration into the global

market, the collapse of the post–Cold War international order and the return of

nineteenth-century-style disorder have altered the CCP’s approach.

Xi has therefore

invested heavily in self-reliance. But as many Chinese intellectuals point out,

the changes in Chinese attitudes toward globalization have been driven as much

by domestic economic challenges as by tensions with the United States. In the

past, China’s large, young, and cheap labor force was the principal driver of

the country’s growth. Now, its population is aging rapidly, and it needs a new

economic model built on boosting consumption. As the economist George Magnus

points out, however, doing so requires raising wages and pursuing structural

reforms that would upset China’s delicate societal power balance. Rekindling

population growth, for instance, would require substantial upgrades to the

country’s underdeveloped social security system, which would need to be paid

for with unpopular tax increases. Promoting innovation would require a

reduction of the role of the state in the economy, which runs counter to Xi’s

instincts. Such changes are hard to imagine in the current circumstances.

A World Divided?

Between 1945 and

1989, decolonization and the division between the Western powers and

the Soviet bloc defined the world. Empires dissolved into dozens of

states, often due to small wars. But although decolonization transformed the

map, the more powerful force was the ideological competition of the Cold War.

After winning their independence, most countries quickly aligned themselves

with the democratic or communist bloc. Even those countries that did not want

to choose sides nevertheless defined their identity about the Cold War, forming

a “nonaligned movement.”

Both trends are in

evidence today, and the United States believes that this history is repeating

itself as policymakers try to revive the strategy that succeeded against the

Soviet Union. It is, therefore, dividing the world and mobilizing its allies.

Beijing disagrees and is pursuing policies suited to its bet that the world is

entering an era in which self-determination and malalignment will trump

ideological conflict.

Beijing’s judgment is

more likely accurate because the current era differs from the Cold War era in

three fundamental ways. First, today’s ideologies are much weaker. After 1945,

the United States and the Soviet Union offered optimistic and compelling future

visions that appealed to elites and workers worldwide. Contemporary China has

no such message, and the Iraq war has greatly diminished the traditional U.S.

vision of liberal democracy, the global financial crisis of 2008, and the

presidency of Donald Trump, all of which made the United States seem less

prosperous, less generous, and less reliable. Moreover, rather than offering

starkly different and opposing ideologies, China and the United States

increasingly resemble each other in industrial policy and trade to technology

and foreign policy. Without ideological messages capable of creating

international coalitions, Cold War–style blocs cannot form.

War–gaming potential conflict in Taiwan, Washington,

D.C., April 2023

Second, Beijing and

Washington do not enjoy the same global dominance that the Soviet Union and the

United States did after 1945. In 1950, the United States, its major allies

(NATO countries, Australia, and Japan), and the communist world (the Soviet

Union, China, and the Eastern Bloc) accounted for 88% of the global GDP. But

today, these countries combined account for only 57 percent of global GDP. Nonaligned

countries’ defense expenditures were negligible as late as the 1960s (about one

percent of the worldwide total). They are now at 15 percent and growing fast.

Third, today’s world

is highly interdependent. At the beginning of the Cold War, there were very few

economic links between the West and the countries behind the Iron Curtain. The

situation today could not be more different. Whereas trade between

the United States and the Soviet Union remained at around one percent of

both countries’ total trade in the 1970s and 1980s, trade with China today

makes up almost 16 percent of the United States and the EU’s total trade

balance. This interdependence prohibits the formation of the stable alignment

of blocs that characterized the Cold War. What is more likely is a permanent

state of tension and shifting allegiances.

China’s leaders have

made an audacious strategic bet by preparing for a fragmented world. The CCP

believes the world is moving toward a post-Western order not because the

West has disintegrated but because the consolidation of the West has alienated

many other countries. In this moment of change, it may be that China’s stated

willingness to allow other countries to flex their muscles may make Beijing a

more attractive partner than Washington, with its demands for ever-closer

alignment. If the world is entering a disordered phase, China could be best

placed to prosper.

For updates click hompage here