By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Why XI Might Prefer Détente

Last week we

projected that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s unprecedented third term as

general secretary would drag the CCP back to the

pathologies of the Mao era and simultaneously push it toward a future of

low growth, heightened geopolitical tension, and profound uncertainty.

At a growing tension

between Beijing and Washington, China’s 20th Party Congress in October

unsettled many outside observers. During the proceedings, not only did Chinese

President Xi Jinping stack China’s all-important Politburo Standing Committee

with loyalists and secure a third term in office, but he also painted his

darkest picture of China’s external threats. Xi called for further increasing

the quantity and quality of China’s already accelerating defense production.

And he appointed a mix of protégés and skilled technocrats to the entire

Politburo to oversee China’s response to the challenge.

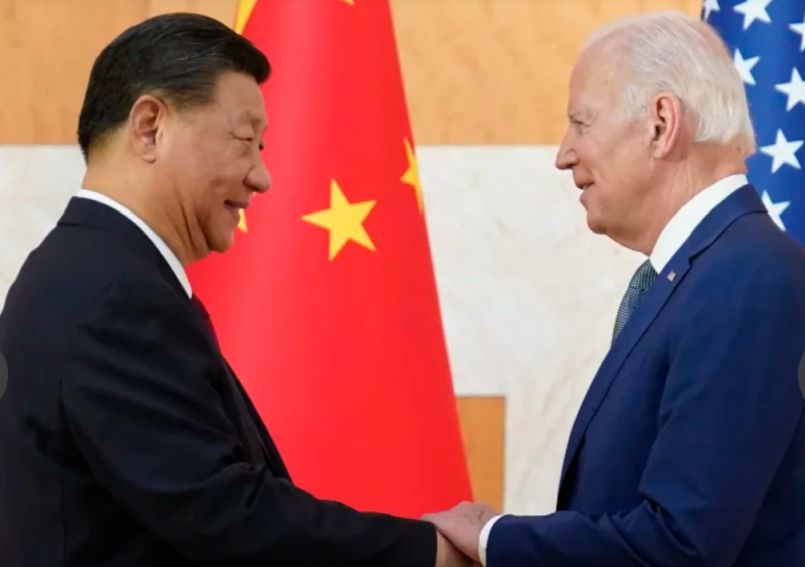

Biden And Xi Meeting Today as Pictured

Previously, Beijing

has withheld escalatory responses that would amount to direct economic warfare

against the United States, such as disrupting crucial supply chains of

rare-earth metals or using untested Chinese regulatory tools such as its “Unreliable

Entity List” and the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law, which could penalize foreign

companies simply for complying with U.S. regulations. But to many

analysts, Xi’s recent moves are a sign of worse. Now that Xi is firmly

ensconced in his third term, some China observers argue that he could move to

retake Taiwan in the next few years, provoking a full-fledged war between the

world’s two most powerful states.

But the new Politburo

is not a war cabinet. Although there is no question that China’s leadership has

grown more prickly and assertive, predictions in the wake of the congress that

Beijing could soon launch a military provocation or that Xi will dramatically

rein in free-market capitalism in favor of a return to statism are wrong. For

all their loyalty to Xi, the party’s new leaders have primarily measured

technocrats. Xi has added many close allies, but they also have strong

connections to China’s private economy and are unlikely to be pure sycophants.

Rather than planning for an aggressive, closed, and highly personalistic China,

the United States should expect Beijing to continue to govern stably and

predictably, if only because China is facing significant challenges that make

the Politburo crave stability.

The 20th Party

Congress is not the first time Xi has spoken about the

world in a menacing tone. In May 2019, U.S. talks with China over President

Donald Trump’s tariffs collapsed in Washington. Shortly after, Xi traveled to

Jiangxi Province on a visit full of symbolism: Jiangxi was the launch pad for

the Chinese Communist Party’s fabled Long March in 1934, when CCP forces

successfully retreated from advancing Chinese nationalists, regrouped, and then

won. “We are now embarking on a new Long March,” Xi said to a cheering crowd at

the Long March memorial site, “and we must start all over again.” He doubled

down in a Politburo meeting a year later, declaring that China was

fighting a “protracted-war” against the United States, in a throwback to On

Protracted War, Mao Zedong’s 1938 book about defeating a superior

foreign enemy.

Yet Xi did not completely upend Chinese doctrine on those

occasions. In each instance, he held fast to the judgment that stability and

economic growth remained the dominant global trends. By declaring that “peace

and development remain the themes of the era,” he parroted a phrase first

coined by Deng Xiaoping—the father of China’s post-Mao reforms. He also said

China was enjoying “a period of strategic opportunity,”: an axiom introduced by

Jiang Zemin, Deng’s successor and another market-oriented reformist. The idea

underlying both concepts is that China enjoys a benign, perhaps even welcoming,

global geopolitical climate. This assessment forestalled Chinese military adventurism

aimed at reshaping East Asia’s balance of power and instead incentivizing the

country’s policymakers to focus on economic growth. Both phrases appeared again

in critical CCP documents from April and June 2022, reaffirming their canonical

standing in party dogma.

That continuity,

however, did not stop Xi from changing Chinese foreign policy. Already in

November 2014, he gave a speech in which he effectively broke with Deng’s

injunction that China should keep a low international profile, even though Xi’s

immediate predecessor—Hu Jintao—had offered a full-throated defense of that

approach just a few years earlier. Indeed, Xi made it clear that he had little

regard for most of his various predecessors’ decisions. In a party resolution

passed in November 2021, Xi condemned the rampant corruption and ideological

laxity under their rule. He put his ideological contribution on par with Mao’s

while downgrading Deng’s. This boosting of Xi’s thoughts at the expense of his

predecessors’ continued in the run-up to the party congress. In July 2022, a

prominent party theoretician penned an article in the CCP’s flagship People’s

Daily extolling Mao’s and Xi’s theoretical achievements while not

mentioning Deng, Jiang, or Hu.

This diminution

campaign cleared the way for Xi to finally excise both phrases—“peace and

development” and “strategic opportunity”—from his political report to the 20th

Party Congress. It is unclear exactly why they were removed, but the West’s

galvanized response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Politburo’s

conclusion that the Biden administration is at least as aggressive toward China

as the Trump administration was probably made a difference. These two factors

are also part of why Xi has made multiple references to “the spirit of struggle,”

a deliberate callback to Maoist rhetoric used when China faced both a hostile

West after the Korean War and an antagonistic one after the Sino-Soviet split.

Although language about peace, development and strategic opportunities all

appear in the political report, the terms are used in isolation and

counterbalanced with references to “risks,” “challenges,” and “hegemonic

bullying.” Xi almost directly attacked the United States for its tariffs and

criticisms, saying China opposes “building walls and fortifications,”

“decoupling and breaking links,” and “unilateral sanctions and extreme

pressure.”

So far, the main

policy implication of Xi’s stiff language has been a campaign to build domestic

industrial strength. At the congress, Xi sketched out his plans to create a

“fortress economy” that is self-sufficient in food, energy, and core

technologies, such as semiconductors and advanced manufacturing. Xi also hopes

to build safer supply chains from Washington’s interference. He seems committed

to increasing China’s military strength abroad and the regime’s security at

home. In the 20th Party Congress report, his “comprehensive national security

concept” had its standalone section, and mentions of “national security” were

up 60 percent over the last report, in 2017. Xi also subtly declared that China

must improve its “strategic deterrence”: a likely nod to China’s August 2021

test of a hypersonic glide vehicle—and an indication that China will

substantially expand its nuclear force.

Economic development

remained China’s “top priority” in the report. But Xi’s new admonition to

“ensure both development and security” puts security on nearly equal footing,

potentially creating more friction with Washington. Xi’s proclaimed desire to

promote a unique “Chinese style of modernization” for developing countries

might spark fears that China’s amorphous Global Development and Global Security

Initiatives are nefarious joint campaigns to challenge the Western

international order directly. Equating development and security could also

heighten U.S. concerns about “civil-military fusion” in China’s economy—fears

that have prompted U.S. President Joe Biden to implement a virtual ban on

exporting high-end semiconductors to China. If Xi merges departments focused on

development and national security at China’s next legislative session—or

creates a new structure to improve coordination and cooperation between them—an

increase in Chinese-U.S. tensions would become virtually inevitable.

Steady As She Goes

Xi’s new leadership

team matches his protectionist and militaristic language in many ways. Several

of the new Politburo members are techno-nationalists with expertise in

important state-led scientific endeavors that have advanced China’s industrial

prowess; they include a nuclear engineer, an expert in material sciences, and

four officials with experience in Chinese defense firms. In the security realm,

Chen Wenqing is the first former head of China’s

civilian foreign intelligence arm to sit on the Politburo. He is joined on the

CCP Secretariat—the Politburo’s executive body—by China’s top cop and a career

police officer turned party disciplinarian, creating the largest contingent of

security officials on the Secretariat in recent memory. Xi’s new chief

uniformed officer and his presumptive next defense minister have overseen

weapons development, highlighting the CCP’s emphasis on continually upgrading

China’s capabilities. Xi’s revamped high command also has two officers who saw

action in China’s border wars with Vietnam and a third who served extensively

in Chinese army units near Taiwan.

Given these

appointments, it is understandable why many analysts believe China is preparing

to upend the liberal order—perhaps even through violence. Major news outlets

across the globe said Xi’s new lineup, especially in the military, proves he is

itching for war. But such narratives are overhyped. Xi’s all-loyalist Politburo

is not designed for near-term conflict with Taiwan (or any other state) but

rather to “harden” China’s system in case war becomes unavoidable. Xi kept an

aging top general on the Politburo, for example, because he is a fellow CCP

blue blood which can be trusted to enforce Xi’s political grip on the military,

not because he fought in China’s disastrous war with Vietnam 40 years ago.

Likewise, Xi promoted defense specialists to Politburo because they achieved

previously unattainable technological breakthroughs, like landing rovers on the

moon, rather than for their weapons-making prowess. And despite the

new language, Xi’s work report still balanced calls for a “fortress economy”

with language supporting markets, suggesting he will govern with a

precautionary approach instead of marching to war.

The idea that Xi’s

new economic team is an incompetent and sycophantic group of statists, also

popular among China observers, is similarly off base. The officials’ career

paths alone belie that caricature. China’s next premier, Li Qiang,

has led all three of China’s top east coast economies and maintains good

relations with private-sector entrepreneurs. His stewardship of the wrenching

Shanghai lockdown raised reasonable questions about whether loyally following

Xi will outweigh his pro-market instincts, but that is nothing new for China:

outgoing Premier Li Keqiang, an unquestioned reformist, earned a similar

black mark for toeing the party line amid controversies earlier in his career.

Li Qiang’s likely economic deputy—Ding Xuexiang—is more of a cipher, but he hails from the

financial capital of Shanghai and will be attuned to the markets. As Xi’s

longtime chief of staff, Ding knows how to please his boss, but he is also

experienced in operating China’s government to address various problems.

Finally, He Lifeng—assumed to be the economy’s new

operational manager—has substantial experience in several of China’s

market-driven special economic zones.

The Biden

administration must understand that China’s new leaders are not just

warmongering statists if it wants to handle an unbound Xi successfully. Right

now, however, it may not. On Taiwan, the administration has touted an

ever-shrinking timeline for possible Chinese military action, and it has

alleged that the Chinese government is impatient about retaking the island.

This messaging may be deliberately alarmist—part of an attempt to tell Beijing

that the United States is ready and watching, thereby deterring an attack. But

it could create a self-fulfilling prophecy if the resulting support to Taipei

hollows out Washington’s official “one China” policy—which recognizes the

Chinese position that Taiwan is a part of China and that the mainland is the

sole legal government of China—and in turn crosses Beijing’s fundamental

redline. Biden officials are more circumspect in describing Xi’s new economic

team. Still, their framing of the Chinese-U.S. rivalry as a competition of

economic and governance systems implies that they expect China’s model will

ultimately fail—a perspective that earns them few friends in Beijing.

That is not to say

Xi’s approach and his new team are the right choices for China or that they

inevitably will succeed. And regardless, Biden must understand that Xi’s power

equals that of Mao—except during a time when China is far more economically

powerful and globally consequential. China’s president is a ruthless and

tenacious leader, full of ambitions that norms will not subordinate: something

the reformist Hu Jintao’s embarrassing and forced exit from the congress

meeting clearly illustrated. By appointing a mix of loyal protégés and

accomplished technocrats to the Politburo, Xi has also made it clear that he is

a man in a hurry, pursuing fast results. He could act rashly and catch

Washington off guard.

But that does not

mean Xi is itching for a fight. Xi’s sense that China faces substantial

challenges may encourage him to lower bilateral tensions. Ding, a leading

Politburo member, unwittingly hinted as much in a lengthy early November

article in the People’s Daily, where he forcefully cataloged

China’s many challenges and arduous tasks over the next five years (and beyond)

and offered a controversial Mao formulation as the correct response. After all,

Mao first lowered tensions with Washington to achieve many of his objectives

more easily. Xi is not looking for a rapprochement, but he might like some breathing

room. Early rumblings that Biden and Xi could hold a lengthy meeting with the

trappings of traditional, modern summits, where both sides use the gathering to

announce commercial deals and other deliverable results, suggested as much. The

real question is whether Biden wants to—or can—seize Beijing’s apparent

interest in a détente to pump the brakes on the relationship’s downward spiral.

For updates click hompage here