By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Why One Muslim Minority Are In Chinese

Detention Camps

For many years already, Beijing launched a brutal crackdown

that swept over 1 million Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslim minorities in

detention camps and prisons in its western Xinjiang Province; members of the

Uyghur diaspora and activists are frustrated over a lack of international

recognition for alleged

atrocities committed

by the Chinese government. These actions have drawn accusations

of genocide from international rights groups and several

Western governments, resulting in sanctions on some top Chinese officials in

Xinjiang. Official documents leaked from

Xinjiang reveal that

people were detained for such trivial causes as having traveled abroad or

simply possessing a passport, communicating with people overseas, performing

daily Muslim prayer rituals, or wearing a veil.

The exiled leader of

the Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights organization. Atajurt provided a crucial

early window into the atrocities happening in Xinjiang, focusing on the

testimonies of ethnic Kazakhs. But in 2019, Bilash was arrested on charges of inciting

ethnic hatred and

forced to end his activism before he fled abroad. As part of a

government-organized visit on January 8 to Xinjiang in cooperation with the

World Muslim Communities Council, a U.A.E.-funded organization, Mustafa Ceric,

who served as grand mufti from 1999 to 2012 and held a variety of other

influential roles within Bosnia’s Islamic community, toured the region along

with a delegation of more than 30 Islamic

clerics and scholars

from 14 countries. The tour received widespread coverage from China’s domestic and international media

outlets, focusing on comments made by Ceric, where he praised China’s growing

global role and “the Chinese policy of fighting terrorism and de-radicalization

for achieving peace and harmony in [Xinjiang].”

“China, by inviting

so-called World Muslim Communities Council leaders to [Xinjiang], is still

trying to deceive the world,” Dolkun Isa, president

of the World Uyghur Congress, wrote on Twitter following the delegation’s tour. “It is a fact

that China has been engaging in a genocidal policy toward Uyghurs, and at the

same time, China declared war against Islam.” Mustafa Prljaca,

adviser to Husein Kavazovic,

Bosnia’s current grand mufti, told

RFE/RL’s Balkan Service that the country’s Islamic leadership had

nothing to do with Ceric’s visit and that the grand

mufti’s office did not agree with his statements about Chinese policies in

Xinjiang.

In response to the

growing scrutiny, researchers and some governments say that Beijing has

orchestrated a global campaign to shape world

opinion about its

abuses in Xinjiang and its treatment of Uyghurs there that consists of

spreading disinformation, search-engine manipulation, tightly managed media

tours, and enlisting social-media influencers to push propaganda and its

narrative to international audiences. “Covert and overt online information

campaigns have been deployed to portray positive narratives about the [Chinese

Communist Party’s] domestic policies in the region while also injecting

disinformation into the global public discourse regarding Xinjiang,” stated a

2021 report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute,

a Canberra-based think tank.

In July of that year,

Bosnian Foreign Minister Bisera Turkovic

signed a joint statement at the UN Human Rights Council along with more

than 40 other -- primarily Western -- countries that expressed alarm about the

human rights situation in Xinjiang and called for an international inquiry. In

response, Milorad Dodik, then the Serbian representative of the Balkan

country’s tripartite presidency, sent an official letter to the UN asking for

Bosnia’s signature to be withdrawn from

the statement.

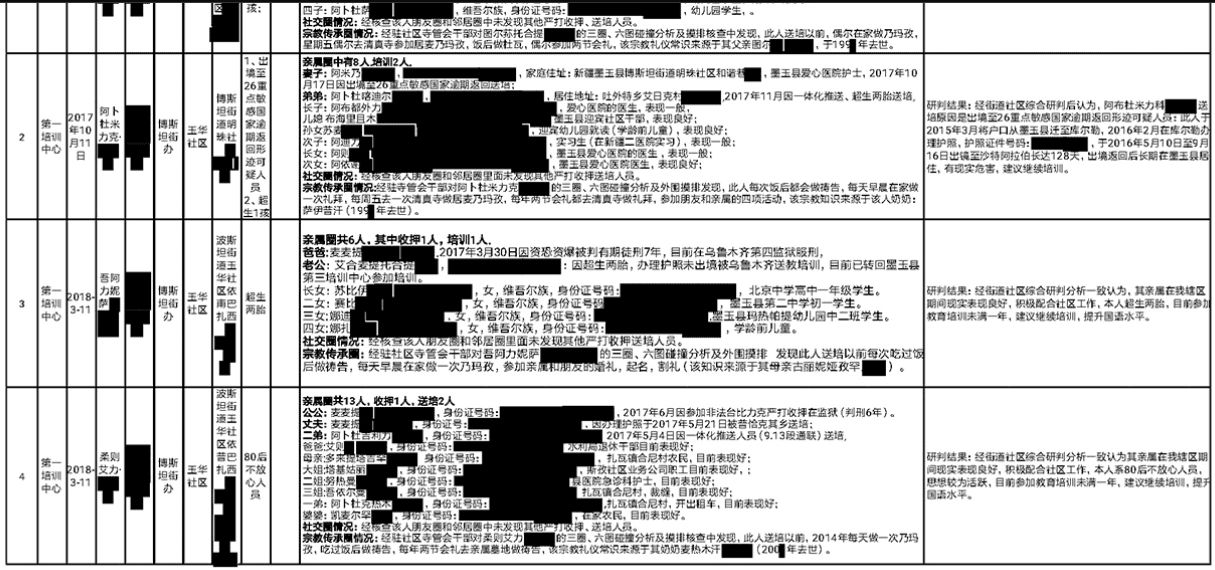

A redacted version of

part of a Chinese government PDF document leaked to CNN, showing records of

detainees in Xinjiang:

Starting in late

2017, Uyghur and Kazakh émigrés from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in

China began hearing frightening reports from relatives and friends at home—or

began losing contact with those relatives and friends entirely. Through early

2018, journalists and researchers began to flesh out the story: in the vast

Central Asian territory annexed by China in 1949, also known to many exiles as

Eastern Turkestan, the government was rounding up people who did not belong to

the country’s Han ethnic majority (including the Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic

group) and locking them in camps. At their peak, these facilities interned

between one and two million people, and detainees were subjected to

psychological and physical torture, rape and sexual assault, forced

administration of pills and injections, persistent hunger, and sleep

deprivation. Beijing at first denied the existence of what the Chinese

government documents and signs on the facilities labeled “concentrated

educational transformation centers.” Still, officials later admitted to

establishing “vocational training centers,” which they claimed would end

extremism and alleviate poverty.

With their clear

echoes of genocides in the twentieth century, the camps prompted outrage from

international organizations, human rights groups, and governments—some of which

sanctioned Chinese companies and officials in response. Although the Chinese

Communist Party dismissed the criticisms as “lies,” it appeared to respond. By

2019, authorities had moved many internees out of the camps, announcing they

had “graduated.” This suggests that the CCP does care about international

opprobrium.

But the change was

largely cosmetic, and most of the internees have not been freed. Many of the

camps have been converted into formal prisons, and detainees were given lengthy

prison sentences, like several hundred thousand other non-Han people who have

been imprisoned since the start of the crisis. Over 100,000 other internees

have been transferred from camps to factories in Xinjiang or elsewhere in the

country. Some Uyghur families abroad report that their relatives are back home

but under house arrest. And Beijing has also been forcing tens of thousands of

rural Uyghurs out of their villages and into factories under the guise of a

poverty alleviation campaign. Today, the total number of non-Han Chinese people

in coerced labor of one form or another may well exceed the number of interned

in camps from 2017 to 2019.

The camps were just

the most famous aspect of the CCP’s broad-spectrum program of assimilation and

repression. The party has also disparaged and restricted the use of the Uyghur

language; prohibited Islamic practices; razed mosques, shrines, and cemeteries;

rewritten history of denying the longevity of Uyghur culture and its

distinctiveness from Chinese culture; and excised indigenous literature from textbooks.

These scars on the cultural landscape remain. The vaguely worded

counter-extremism and antiterrorism laws, implemented in 2014 to intern people

for everyday religious and cultural expression, are still on the books. The

infrastructure of control that made southern Xinjiang look like a war zone a

few years ago—intrusive policing, military patrols, checkpoints—is less visible

now. But that is because digital surveillance systems based on mobile phones,

facial recognition, biometric databases, QR codes, and other tools that

identify and geolocate the population have proved just as effective at

monitoring and controlling residents.

The state continues

to incentivize and likely coerce, Uyghur women to marry Han men while

promulgating propaganda promoting mixed marriages. (Uyghurs very rarely married

non-Uyghurs before the current crisis.) Uyghur children are being

institutionalized in boarding schools, where they are forced to use the Chinese

language and adopt Han cultural practices. There is little data about these

schools but escaped children tell of beatings and hours of basement confinement

for speaking Uyghur. If the “educational transformation centers” were

reminiscent of twentieth-century concentration camps, the Xinjiang boarding

schools have re-created the brutal residential institutions designed to

deracinate indigenous children in Australia, Canada, and the United States.

They also contribute to China’s broader colonial policy to Sinicize the region

by moving Han people into Xinjiang and suppressing Uyghur birth rates.

Despite the ongoing

abuses, the world has paid little attention to the atrocities in Xinjiang over

the last few years. Instead, the focus has drifted to other news relating to

China—primarily the COVID-19 pandemic. Beijing was able to convene the Winter

Olympics as planned in February 2022, with only symbolic protests from

democratic countries. The atrocities did not stop Chinese leader Xi Jinping

from being named head of the CCP for a historic third term or from stacking the

Politburo standing committee with close loyalists. It has not prevented him

from meeting with foreign leaders, including U.S. President Joe Biden.

For now, it may seem

as if President Xi is getting away with his

brutal actions in Xinjiang. But the saga in the province is still ongoing. U.S.

and European sanctions could impinge more on China’s economy as time passes,

provided governments vigorously enforce them. These economic costs would come

on top of the severe reputational costs that Beijing has incurred for its

behavior, including worsened relations with Europe and the United States. It is

unclear if these penalties will ultimately matter to Xi, who now wields nearly

unconstrained political power and is willing to subject his country to economic

and social pain in pursuit of his aims. But Xi is capable of correcting course

when his policies become disastrously costly. If the world keeps up the

economic and rhetorical pressure, it can convince China to end its efforts to repress

and assimilate the non-Han people of Xinjiang.

Too Little, Too Late

When news of the

internment camps in Xinjiang broke, it fell to the United States to set the tone

for how the international community would respond. Yet the United States was

slow. Although journalists, researchers, and a few Chinese Kazakhs and Uyghurs

who fled the country had made the extent of the atrocities blatant, Congress,

despite the rare bipartisan agreement, failed to pass a bill addressing Uyghur

human rights quickly. According to The South China Morning Post,

U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin did not want anything to upset his

negotiations with Beijing over a trade deal. As The New York Times has

reported, Apple, Coca-Cola, and Nike also lobbied to weaken the sanctions bill,

lest it harms their business interests.

But Washington’s

worst mistake came from U.S. President Donald

Trump. According to his former national security adviser, in June 2019, at

the height of the internment, Trump told Xi in person that the concentration

camps were “exactly the right thing to do.” These words’ disastrous impact on

millions of human

lives should be remembered with Trump’s rhetoric supporting Putin’s adventurism

in Ukraine and his attempt to extort Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky as

among the former president’s gravest sins in office. It is conceivable that Xi,

like Putin, has isolated himself amid yes men and is prone to doubling down on

irrational, self-defeating decisions. Trump’s vocal greenlights—one of the few

comments on Xinjiang that Xi may have heard from outside his circle—likely

prolonged and deepened the ethnic cleansing.

Still, the administration

eventually listed several Xinjiang individuals and entities for export bans and

global Magnitsky sanctions, and Congress ultimately passed the Uyghur Human

Rights Policy Act in 2020. On the last full day of the Trump administration,

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo determined that China was committing

genocide and crimes against humanity in Xinjiang. His successor, Antony

Blinken, affirmed this decision. In December 2021, Biden signed a new, stronger

sanctions law—the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act—which prohibited imports

of “any goods, wares, articles, and merchandise mined, produced, or

manufactured wholly or in part” in Xinjiang unless they are proven not to be

linked to forced labor. Absent reliable third-party supply chain auditing in

the Uyghur region, this law effectively bans imports of nearly everything

connected to Xinjiang. To date, over 100 Xinjiang-related U.S. sanctions are in

place against Chinese companies, government agencies, and individuals.

Other governments

have joined Washington’s campaign. Canada, the United Kingdom, and the European

Union have all sanctioned the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau and the Xinjiang

Production and Construction Corps, a massive state-owned conglomerate dedicated

to colonial exploitation and settlement in the Uyghur homeland. Belgium, the

Czech Republic, France, Lithuania, and the Netherlands have joined Canada, the

United Kingdom, and the United States in formally denouncing the CCP’s Xinjiang

actions as genocide. Nongovernmental and intergovernmental organizations,

including the independent groups Uyghur Tribunal and the Inter-Parliamentary

Alliance on China, have reached similar findings about the nature of Beijing’s

actions, which they have backed up with copious documentation and opinions from

international jurists.

Unfortunately, the

most important international organization—the United Nations—has a more mixed record.

In August 2018, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

forced Chinese officials to publicly explain what was happening in Xinjiang for

the first time. A Chinese spokesperson responded two days later by denying the

existence of reeducation centers already documented by researchers, including

from satellite photos. But after that staunch initial challenge, the UN has

tiptoed around the issue. Beijing has won whenever UN member states have had to

take sides over Xinjiang. Twenty-two nations (18 European countries, Australia,

Canada, Japan, and New Zealand) signed a letter to the UN High Commissioner on

Human Rights calling for China to stop the mass detentions in Xinjiang.

But Beijing quickly mobilized 37 states to sign a counter-letter that all was

well in the Uyghur Region. Last June, 19 UN Human Rights Council members voted

against a motion to debate the contents of the council’s critical report on

human rights in Xinjiang, and 11 members abstained. Only 17 voted to hold the

debate.

China’s success in

such showdowns exploits the unwillingness of states with poor human rights

records to condemn abuses elsewhere. It depends on the fear that angering

Beijing might cut off Chinese investment. Cuba voted against debating the

report, and even Ukraine abstained. Beijing also exerts intense

behind-the-scenes pressure to shape how the UN approaches Xinjiang issues. This

strategy was particularly evident, if cloaked, in the High Commissioner for

Human Rights activities. After a prolonged negotiation, High Commissioner

Michelle Bachelet visited Xinjiang in May 2022 on a five-day COVID-19 “closed

loop” tour that she stressed was “not an investigation.” In an awkward press

conference concluding her visit, Bachelet echoed Beijing’s explanations that

the camps were counterterrorism and job training programs. She adopted Chinese

terminology, referring to the internment facilities as “vocational education

training centers”—even though, according to former detainees, no vocational

training took place in the camps. Beijing’s control over Bachelet’s agenda and

selection of the people she talked to likely set the parameters for what her

short visit could achieve.

But ultimately, the

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a report far more critical of

China’s behavior. When finally released, a few minutes before midnight on the

last day of Bachelet’s term as High Commissioner, the report detailed grave

concerns that Beijing was committing crimes against humanity in Xinjiang,

backed up by voluminous documentary evidence and interviews with 40 Kazakh,

Kyrgyz, and Uyghur firsthand witnesses. CCP authorities who had gloated over

Bachelet’s May press conference now denounced her report as “a patchwork of

false information that serves as political tools for the U.S. and other Western

countries to use Xinjiang to contain China strategically.” But the report never

applied the UN’s definition of genocide to Xinjiang—a glaring omission. And the

failure of the Human Rights Council to even debate the report rendered it a

dead letter, at least within the UN.

What Works

It is still hard to

judge the impact of sanctions on the economy and officials in Xinjiang. Import

bans are difficult to enforce, and fruits and nuts in packaging indicating

their Xinjiang origins were for sale in Asian markets throughout the

Washington, D.C., area in 2022—although, after activists publicized the fact

that fruit was still getting through, U.S. Customs and Border Protection seized

several shipments of Xinjiang red dates in New Jersey in January 2023. Customs

agents are more focused on interdicting Chinese textiles, but cotton from

Xinjiang hides in opaque supply chains and is processed in third countries into

garments that stock U.S. stores. So far, any pain that sanctions may have caused

has been masked by the more severe economic impact of China’s COVID-19

lockdowns (which were implemented in Xinjiang harder and for longer than

anywhere else). In any case, the CCP has shown itself willing to spare no cost

in pursuing Xinjiang policies. The conversion of the province into a digitally

securitized gulag was costly, but Beijing did not blink. The budget to support

Han settlers in the Uyghur Region seems inexhaustible.

Nevertheless, as

COVID-19 lockdowns lift and the sanctions may begin to bite as time goes on.

They could, for example, prompt international and potentially even Chinese

corporations to realize that connections to Xinjiang put them in a precarious

position. The U.S. government has signaled that it considers corporate compliance

with the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act just as important as compliance

with the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. That means that companies importing

goods to the United States from Xinjiang, and in some cases from elsewhere in

China, have to actively prove that such products were not tainted by forced

labor. Third-party auditing, such as that done by the Better Cotton Initiative,

is impossible in Xinjiang thanks to official Chinese interference, so global

firms currently dealing with Xinjiang may conclude that they have to leave the

region and perhaps the country. Already, manufacturers of solar energy

equipment are developing the capacity to produce polysilicon (of which 50

percent of the world’s supply now comes from Xinjiang) in other countries.

Nor are the sanctions

the only penalty Beijing is paying. The CCP’s “Wolf

Warriors” may respond to the international outcry with indignant retorts

and a flurry of disinformation. But the diplomatic and reputational damage to

China is real—and perhaps even more significant than the potential economic

penalties. The CCP, for example, had a chance to improve Chinese-European ties

after the Trump administration’s isolationism and insults upset U.S. allies.

But by responding to EU sanctions over Xinjiang with an ill-considered battery

of sanctions on European Parliament members across the political spectrum, Beijing

squandered the opportunity. Instead, China’s tit-for-tat effectively scuttled

the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with Europe, a trade deal it had

spent years negotiating.

The brutality of CCP

colonialism in Xinjiang has devastated China’s relationship with Taiwan. In

December 2022, Taiwan’s legislature passed an unprecedented cross-party

resolution recognizing China’s “genocide” against the Uyghur people. The

Xinjiang atrocities are a significant reason why “one country, two

systems”—long the CCP formula for “reunifying” mainland China with Taiwan—is

dead, and Beijing’s toolbox for peacefully addressing the Taiwan issue is

thereby depleted. With military force looking like the only option, the CCP’s

increased bellicosity toward Taiwan has exacerbated tensions with the United

States. In this regard, Xi’s effort to enhance China’s security through a

crackdown in Xinjiang has backfired spectacularly.

The CCP’s attack on

the native peoples of Xinjiang has also shredded Beijing’s international

reputation, at least among the world’s advanced economies. People in democratic

countries have long expressed concerns about human rights in China—this has

been a constant. But according to polling by the Pew Research Center, the

moment when opinions of China in advanced economies turned dramatically

negative occurred throughout 2017 and 2018. This was before the Hong Kong protests, the pandemic, and the CCP

supported Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The sharp decline does correspond with

Trump’s trade war against China, but outside of the U.S. Republican Party, few

sympathized with his unilateral imposition of tariffs. That leaves the

concentration camps as the remaining well-timed independent variable—the factor

most likely to have turned opinions in Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea,

the United States, and Europe against Beijing.

China, of course,

does not need to heed its own people’s opinions when making policy, let alone

those of other states. The country’s government is now a personalist

dictatorship, and currently, it seems that only Xi could decide to reverse

course in Xinjiang. This does not inspire confidence. As the prolonged

zero-COVID policy vividly illustrated, China’s leader displays a reckless

disregard for what have been bedrock principles of the Chinese party-state

since 1979: prioritizing economic growth, preserving amicable access to the

advanced economies of the world, and maintaining a harmonious balance among

China’s ethnic groups.

But zero COVID also

suggests that Xi, and the Chinese party-state, can change course. After

protests made it clear that China could not lock down indefinitely, the CCP

lifted its controls, implicitly acknowledging that COVID-19 will not go away

and that the economic and social cost of trying to contain it was simply too

high. The Uyghurs are not going away, either. If the world maintains its sanctions

and scrutiny over time, it can make the price of brutalizingChina’ss

minorities unacceptable.

For updates click hompage here