By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

The way

to Zionism

Back in Mach 2018, The New Yorker published an article

titled "Why Jewish

History Is So Hard to Write" the

article, in particular, criticizes the two most common approaches to

writing Jewish history. Intrigued by this critique we decided on a third

approach.

For many generations, Jewish communities in the

Russian Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth enjoyed a large degree of

administrative and cultural autonomy, whether through the Council of Four Lands

in Poland or the elected local kahal Jewish community committees in tsarist

Russia. In many senses, Jewish autonomy under autocracies formed the basis of

Simon Dubnow’s later thinking about Jewish

autonomism, the cause of Jewish autonomy in the Diaspora, including within a

future democratic, multicultural Russia.

Between 1580 and 1764, the Council of Four Lands was

principally in charge of collecting taxes from the Jews on behalf of the royal

treasury. Sometimes regarded as the heir to the Sanhedrin of antiquity, the

council functioned in what is known as Greater Poland, Little Poland, Galicia

(with Podolia), and Volhynia, and its members were

acknowledged as the leaders of Polish Jewry in secular affairs.

The council met twice a year to discuss and arrange

interactions with the authorities on both religious and secular matters. For

the first hundred years of its existence, leading rabbis were the dominant

force, but in time, the difference between the secular council and the

rabbinical leadership became more and more pronounced. In 1688, the council

forbade rabbis from interfering in matters of taxation. Five decades later, in

1739, it reiterated this demand and insisted that the rabbis confine themselves

to matters of religion.1

The shift in the council’s leadership away from the

rabbis and toward lay leaders were influenced by the budding Enlightenment

movement in western Europe and the growing desire of Polish Jews to strengthen

their oversight of their communal representatives.

The Jews of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would

experience a profound change in the coming decades after the tsarist empire

annexed the Polish provinces and introduced a new policy of coercive

governance, combined with limited integration for the minorities under its

rule. In 1791, imperial authorities created the institution of the kahal as a

decentralized successor to the council. Kahal committees were formed in the

roughly 1,000 separate Jewish communities in the Pale of Settlement. Each

committee numbered five to nine members and functioned as an administrative and

enforcement body under the auspices of the imperial regime, and executed its

will. It soon became the central element in Jewish life. According to historian

Benjamin Pinkus, even before the kahal system, Jewish autonomy “was fuller than

that conceded to other national and religious minorities within Belorussia.”2 The kahal

was governed according to Jewish law and was responsible for collecting taxes

from Jews, representing and policing members of the community, and issuing

identity documents.

During the reign of Alexander I, some called for the

integration of the Jews as “good and useful citizens.” But this budding

liberalism and the opening it offered for western-style enlightenment lacked

the administrative foundation for any meaningful reform. The tsarist regime

preferred a policy of segregation based on the kahal structure as an effective

means of control. At times, Tsar Alexander I tried to form a Jewish advisory

body and even tried to help to combat blood libels.

Under the tyrannical rule of his successor, Nicholas

I, this dialogue-oriented attitude gave way to a harsh dynamic of arbitrary

coercion. In 1827, Nicholas abolished the practice of purchasing exemptions

from military service and ordered Jewish community leaders to supply conscripts

as a collective responsibility; with this, the kahal system’s moral authority

quickly waned in the eyes of many Jews, as did solidarity and confidence in

their own representatives, whom they now perceived as lackeys of the tsarist

regime. Jews accused these community leaders of corruptly exploiting their

power to decide who was, and who was not, doomed to conscription. Any contacts

with the authorities that were perceived as excessively close evoked suspicion

and any cooperation with the government’s proposed reforms were feared as the

prelude to forced Christianization. Nonetheless, the kahal system remained the

only structure that enabled the Jews to enjoy a high level of communal cohesion

under their own elected leadership.3

In 1844, the Russian government changed its policy

toward the Jews overnight. Their autonomy was deemed too broad and threatening,

and Tsar Nicholas abolished the kahal system. A year later, it was decreed that

within five years, the wearing of traditional Jewish garb would be totally

forbidden. According to Benjamin Pinkus, the abolition

of the kahal system meant that elected Jewish leaders were stripped of

their powers, and “synagogue authorities were forbidden to exercise any

pressure, except reprimand and warning.”4

Even without the kahal committees, “Jewish communities

continued to deliver taxes and conscripts, as the state required of them.”5

Over time, however, their internal leadership lost their status and powers.

Rebellious youngsters and intellectuals, as well as entrepreneurs and rich

merchants, challenged the old guard and its traditional system of control. The

community was divided over the key question that keeps recurring: Who speaks

for the Jews, and on what authority?

The tsarist regime’s erratic flip-flopping between wanting

to rule the Jews as a collective and fearing that their cohesion would

constitute a threat reflected its growing apprehension about national

minorities in general. The Poles, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, and Caucasian

peoples all awaited the opportunity to assert their independence. Tsar

Nicholas’s ferocity and frequent, unanticipated policy swings compelled the

Jews to reconsider their future. Increasingly concerned that he would take

devastating steps against them, they came up with innovative initiatives to

ensure the continued existence of their collective life outside (or after) an

imperial Russia.

However, most residents of the Pale of Settlement were

unaffected by the romantic ideas of the Enlightenment in Germany and could

conceive of no solutions beyond their traditional way of life. Hasidic Judaism

remained the dominant force among Russian Jewry until the second half of the

nineteenth century. Under the rule of Alexander II, more and more educated Jews

began trying to fit into the empire along the lines of the western European

model, as fully equal citizens.

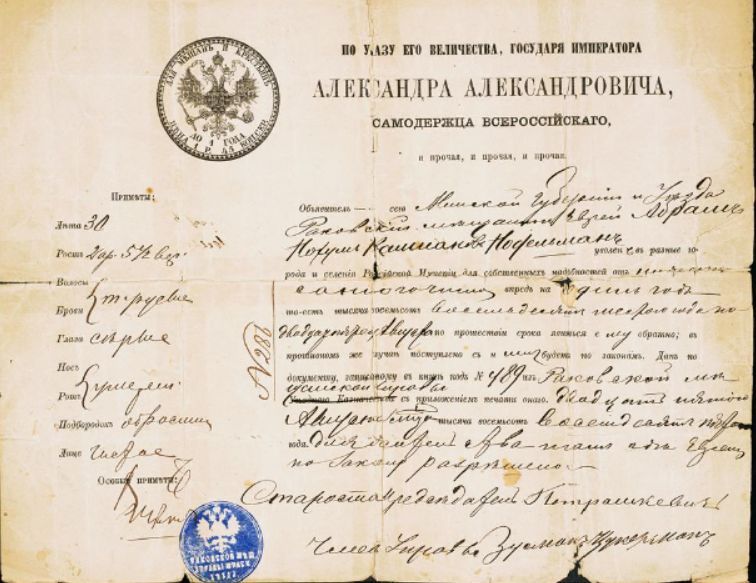

The residence rights accorded to these “Makov Circular Jews” always rested on a shaky legal

foundation, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs withdrew the circular in 1893.

Image of a temporary permit to travel for business

outside the Pale of Settlement:

The reforms during his reign, the upheavals in western

Europe, and the revolutions of 1848 laid the foundation for the emergence of

anti-establishment Jewish nationalist movements. They fed upon the socialist

and liberal revolutionary trends in the West while also drawing inspiration

from the Bible and ancient Jewish sovereignty. After Russia’s defeat in the

Crimean War, Alexander II became increasingly dependent on the taxes paid and

services rendered by affluent and educated Jews. They became indispensable to

the rehabilitation of Russia’s infrastructure, and since the regime was so

dependent on private capital, a small cadre of merchants became significant

financial players for the Russian government.

The new Jewish elites also became the principal

mediators between the imperial regime and their own communities. In the 1870s,

wealthy Jews, notably the Günzburg family, were known for their philanthropy

and efforts to sway the government on Jewish affairs. They succeeded in getting

some of the restrictions on settlement abolished, as well as expanding the

Jews’ freedom of occupation outside the Pale. Their role was similar to that of

the court Jews of central Europe after the Thirty Years’ War, and they secured

an elevated legal status for themselves.6 These developments and Tsar

Alexander’s reforms spurred an internal debate about the opportunities and

dangers inherent in Russification versus the preservation of a distinct Jewish

existence. Some of the wealthy and educated Jews in cities such as Odessa and

St. Petersburg were active in reshaping community life with an emphasis on

liberal Jewish-Russian integration.

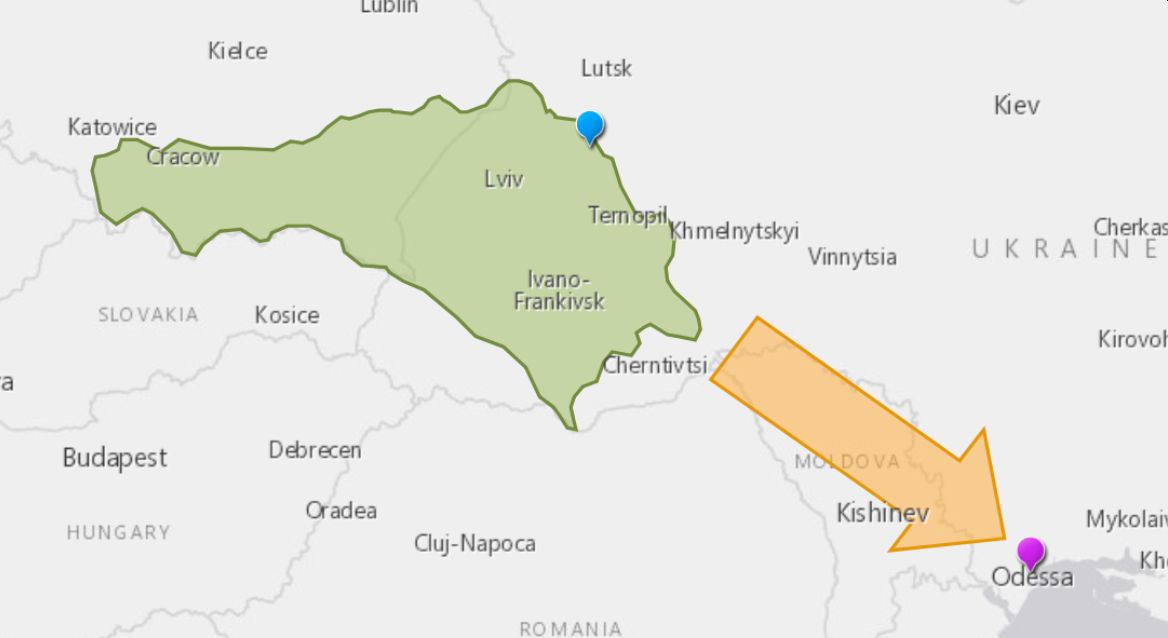

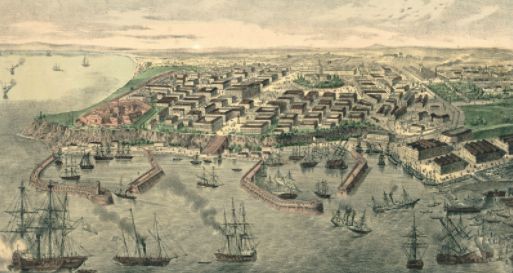

The story of Odessa is a

fascinating example of Jewish flourishing in eastern Europe. In 1790, according

to an unofficial census, there were a few hundred Jews living in the city,

mostly petty traders. By 1860, their ranks had swelled to 17,000, about

one-quarter of the city’s population. By the turn of the century, Odessa was

spoken of as a “Jewish city” and the Jews had become its economic engine, and

in the early twentieth century, two-thirds of the craftsmen and industrialists

in Odessa were Jews. Odessa, in the words of historian Charles King, “was New

Russia’s answer to the shtetl,” a place where Jews were not isolated. Instead,

they fit into society, were nourished by the prevailing enlightenment, and were

optimistic that they could convince the Russian authorities of their value.

Imperial authorities cooperated with the modernizers

by banning the wearing of the kapotah, the

knee-length jacket donned by Orthodox Jewish men, who were now battling for the

survival of their traditional way of life. They sometimes used underhanded

methods to do this, such as leveling false accusations of subversion against

poet Judah Leib Gordon, one of their harshest critics. They reported him and

his wife to the Russian authorities, who banished them on the pretext of

anti-tsarist subversion.

Hasidic Jews saw Odessa as a den of Jewish thieves and

heretics. In Fishke the Lame (The Book of Beggars), by S. Y. Abramovitsch, the father of Yiddish literature known by his

pen name Mendele Mocher Sforim,

the main character, Fishkeh, sums it up by saying:

“Your Odessa is not for me.”7

Among the Jewish intellectuals in Russia were early

Zionists who preached progress but condemned the Western tendencies toward

assimilation. They produced flourishing Hebrew literature that drew upon

biblical sources and extolled the glory of the Jewish sovereignty of ancient

times. Avraham Mapu (1808–1867) became one of the most important heralds of

modern Hebrew literature, arousing the national consciousness of young Jews

with his 1853 book Love of Zion, the first modern Hebrew novel.

Mapu blazed a path for the celebrated writer Peretz Smolenskin (1842–1885), who called for the revival of

Hebrew nationalism and denounced Jewish integration in Russia as a shameful

surrender on the part of an ancient nation. Smolenskin,

influenced by the Polish national uprising in 1863, condemned both the rabbinic

establishment and the forces of assimilation. Having grown up in a small

village in Byelorussia and having been a fervent rebel against the yeshiva

world he was raised in, Smolenskin was also the

harshest and most prominent critic of Reform Judaism and the Enlightenment

ideas of Moses Mendelssohn, which he was exposed to after moving to Odessa. He

continued his relentless struggle against them from Vienna, where he founded

the Hebrew monthly Hashachar (“The Dawn”), devoted to

the revival of the Hebrew language, in 1869.

In advocating Hebrew nationalism as a substitute for

assimilation, Smolenskin was advancing a similar

ideology to Moses Hess, but his was based on and couched in the Hebrew

language. Like Hess, and unlike other Russian Jewish intellectuals who admired

what modernity and enlightenment had achieved for their brethren in the West, Smolenskin condemned the Reform model for making Judaism an

empty, lifeless, universal religion. He despised it for erasing the yearning

for Zion from the liturgy, for abandoning Hebrew and replacing it with German,

and for giving up the solidarity of the People of Israel and their symbiosis of

nation and religion. He argued that religion and nationalism went hand-in-hand

in Judaism, and the Hebrew language was the essential foundation of both. Those

who renounced the use of Hebrew in their prayers were betraying their people

and their religion; to his mind, without the Hebrew language, there was no

Torah, and without the Torah, there was no Jewish nation.8

On the spectrum between Orthodoxy, which wanted to

remain aloof from the rest of the Russian Empire, and the forces of innovation

and modernity, which sought integration and progress within the empire, there

were also the voices of some educated rabbis who, decades before Pinsker and

Herzl, emphasized that a commitment to Jewish nationhood was no less important

than a commitment to religion, and perhaps even took precedence. They believed

the preservation of the Jews’ tribal nature mandated them to maintain strong

ties to their historical homeland and to Hebrew as an everyday language, not

only as a sacred tongue. These pre-Zionist rabbis spoke in messianic terms of

the “Restoration of Israel.” They were inspired by rabbis from outside the

Russian Empire, most prominently Nachman Krochmal, Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, and Judah Alkalai, all

of whom were early harbingers of Religious Zionism in the Land of Israel. The

ability of Orthodox rabbis to adopt these messianic and revolutionary calls for

settlement in what was then a neglected corner of the Ottoman Empire is a

testament to the latent potential within the Jewish religion to adapt itself to

the world of modernity.

The succession of Alexander III

By 1880, Russian Jews could still not integrate along

with the western European model, but they did enjoy a reasonable level of

personal and public security, like other imperial minorities, both in the Pale

of Settlement and the cities. The tsarist regime did not degenerate into mass

murder, notwithstanding some violent, arbitrary outbursts on the government’s

watch, as well as substantial oppression and discrimination. But the

assassination of Alexander II in 1881 and the succession of Alexander III led

to an abrupt change in the lives of Russia’s Jews.

In response to the chaos caused by a series of such

expulsions in 1880, the Minister of Internal Affairs, Lev Makov,

issued a ministerial circular dated 3–15 April 1880, permitting Jews who had

settled illegally before that date to remain in place. The residence rights

accorded to these “Makov Circular Jews” always rested

on a shaky legal foundation, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs withdrew the

circular in 1893.

A major revision of the Pale occurred in the wake of

anti-Jewish pogroms of 1881–1882 and continued at

differing levels of intensity and capriciousness over the next two decades with

the backing of the regime. The tsars directly encouraged harsh legal measures

and indirectly approved “spontaneous” attacks on Jews. Every day brought fresh

peril, and their fear of this arbitrary violence disrupted their vision of

progress and integration under the Romanov monarchy. Even the flourishing

community of Odessa, about whom the Yiddish phrase “You

can live like a king in Odessa” was coined, was abruptly transformed from

being a place of great hope for tolerant cosmopolitanism into a place of anti-Semitic

chaos. As the Golden Age in Spain, the promise and calamity of Odessa were a

repetition of what could happen to the Jews without Jewish sovereignty.

This insecurity and chaos gave a boost to Zionism and

the forces of liberalism. It also strengthened the spirit of the socialist

revolution, although in the early years of the twentieth century, up to the

October Revolution, Jews “broadly rejected socialism in any guise…as the

solution to the problem of the Jews in Russia.”9 Despite this, many who were

motivated by the winds of secularization and political instability wanted to be

part of the overthrow of the autocracy.10

In the end, however, the irresistible allure of the

American Dream and the drive to migrate westward proved supreme. Between 1881

and 1914, two million Jews left the Russian Empire for the United States,

accounting for some 80 percent of their emigration from eastern Europe. Some

brought revolutionary, left-wing ideas to the US and featured among the leaders

of its socialist and communist movements. Only a handful of Russian Jews went

to Palestine, many of them influenced by the Lovers of Zion (Hibat Zion) movement,

which had become the exemplar and catalyst of organized Zionism in Eastern

Europe.

The American Jewish community was transformed by this

mass migration. With time, the United States would become the most important

Jewish community in the world. However, toward the end of World War I, there

were still more Jews in the teetering and soon-toppled Russian Empire than

anywhere else in the world because of tremendous natural growth rates, despite

the trauma of the pogroms. At the turn of the twentieth century, the number of

Jews in Russia was estimated at between five and seven million.11

The Kishinev pogrom

The constant fear of pogroms and revolutionary ferment

drove many Jews to political activism. Disgusted at the passivity and fatalism

of their parent's generation, young Jews refused to accept further affronts to

their dignity or to wait to be slaughtered. They mobilized to fight the

violence and depredations against their people at all levels of society and the

state. The Jews of imperial Russia reached their breaking point with the

infamous Kishinev pogrom of 1903.

Many Jews realized that eastern Europe had become a

deathtrap. But those who were so versed in commemorating calamities were also

adept at denying reality and snapping back to old routines. A debate emerged:

What should the future hold for the Jews of the Russian Empire? They grappled

with many different ideas, both before and after the overthrow of the Romanovs

in 1917, including Jewish sovereignty and new ways of living in the Diaspora.

At one end, Zionism called for the “negation of the diaspora” and the creation

of a Jewish state. On the other, there were demands for full integration in the

Diaspora based on civil, economic, and political equality. Yet others called

for Jewish autonomy in the Diaspora.

Jews also debated two models of cultural autonomy

after the fall of the tsars; one model envisaged the Jews as a minority like

any other recognized national group in a proletarian Russian state while the

other saw them enjoying self-rule as part of a federative arrangement in a

liberal state in which national groups would have cultural (but

non-territorial) autonomy. The latter was the vision of Simon Dubnow, who declared:

It is our duty to fight against the demand that the

Jews give up their national rights in exchange for rights as citizens…. Such a

theory of national suicide that demands that the Jews make sacrifices for the

sake of equal rights, the like of which are not demanded of any other

nationality or language group, contradicts the very concept of equal rights and

of the equal value of all men.12

One element cropped up in every discussion of the

Jewish future, the definition, status, and location of the Jewish homeland. In

the dispute between advocates of sovereignty and those who favored a

diaspora-based solution, the appearance of the Hibat Zion movement gave a

significant boost to the Zionist idea. However, Zion argued that Jews would

forever be foreigners in Russia, and the way out of their distress was

emigration to their historic homeland. Diasporists

and proponents of autonomy emphasized the concept of “hereness”, which meant

that Jews belonged to the places where they lived, just like any other

nation.

Prominent among the diaspora advocates was the Bund

(Yiddish for “union”), a movement founded in 1897 as a “General Union

of Jewish Workers” in Russia, Poland, and later, Lithuania. It was the

first social-democratic organization in the Russian Empire and became a mass

movement. As such, it was the most modern and popular diasporic model in

eastern Europe and a key component in the formation of the socialist movement

in Russia and the pan-European left.

There were two contradictory streams within the Bund,

one universalist and the other specifically Jewish. The first advocated unity

with all socialist movements, Jewish and non-Jewish, for the sake of the

proletarian class struggle; the second called for joining with other Jewish

movements to preserve and bolster Jewish particularity and national solidarity.

The Bund’s attempt to maintain an independent Jewish entity within the Russian

Social Democratic Labor Party created internal contradictions and provoked

clashes with both Jewish and non-Jewish bodies. In Jewish circles, its

universalism aroused opposition due to the fear of assimilation and erosion of

tradition.13 But among Russian socialists, the majority, including Lenin in his

early role as the socialists’ leader-in-exile, saw the Bund’s goal of becoming

an independent ethnonational party as a threat to the unity of the working

class.

In 1903, Lenin contended that the Jews had long ceased

to be a nation, “for a nation without territory is unthinkable.” He dismissed

the notion of diaspora nations in general and of a Jewish diaspora nation in

particular, claiming: “The idea of a Jewish nationality runs counter to the

interests of the Jewish proletariat, for it fosters among them, directly or

indirectly, a spirit hostile to assimilation, a spirit of the ‘ghetto.’”

Historian Zvi Gitelman writes that “for Lenin, there was no Jewish nation, only

a ‘Jewish Problem’,” and this problem would only be solved if the Jews

assimilated and abandoned their distinct cultural identity.14

The Bund never succeeded in finding the right formula

to ensure the survival of the Jewish tribe in alliance with other socialists.

At the same time, Jewish thinkers proposed two other agendas that were not as

politically influential as the Bund’s but still had an impact. The more

important of these was Jewish autonomism, Simon Dubnow’s

vision of Jewish autonomy as a diaspora nation. The other was Yiddishism,

socialist intellectual Chaim Zhitlovsky’s idea for a

“Yiddish language community” to replace the Jews’ religion-based identity,

which he thought was going to disappear. Zhitlovsky’s

form of autonomy would first be established in the multicultural Russia that

would emerge from the embers of the revolution. He suggested that Yiddish would

be the language of instruction in schools and the working language of other

institutions. Yiddishists held a conference in

Bukovina in 1908 and declared Yiddish “a national language of the Jewish

people.”15

Zhitlovsky was something of a Zionist before taking a sharp turn

and backing the Bolsheviks. Realizing his mistake, he later fled to the United

States and promoted the idea of turning the Land of Israel into a Yiddish, not

Hebrew, national cultural center. He predicted that masses of Jews would stream

to a Yiddish-speaking national home. Historian Zvi Gitelman sardonically said:

“Whether Zhitlovsky seriously thought that Sephardic

Jews would adopt Yiddish, or whether he simply ignored their existence, is not

clear, but telling.”16 Zhitlovsky died in Canada,

together with his eccentric proposal.

Simon Dubnow showed some

sympathy for Yiddishism but did not see it as the heart of the national culture

of eastern European Jewry. For him, the Jews were multilingual people and

speakers of Russian, Yiddish, and Hebrew. Dubnow, a

gifted historian, considered himself a missionary for Jewish history. He made a

great contribution to the study of eastern European Jewry and called upon them

to proudly brandish their past as the key to ensuring their national future. He

advocated the study of history and the documentation of Jewish life as a modern

alternative to Torah study. He also earned the widespread recognition of social

scientists as the leading expert in the field of diaspora studies, a branch of

the study of nationhood.

Dubnow

was a member of the intellectual elite and emerged in the Byelorussian part of

the Pale of Settlement; he later moved to St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kaunas,

Berlin, and Riga. The Kishinev pogrom of 1903 shocked him deeply and led him to

cooperate with Ahad Ha’am and Hayim Nahman Bialik in investigating the

massacre. “Stunned by the thunder of Kishinev,” he later wrote, “we each sat in

our own homes in Odessa with broken hearts and seething with impotent anger.

When the horrendous news reached our town, so close to the martyrs, the pen

dropped from my hand and I could not return to my historical work for many

days.”17

Dubnow, Ahad Ha’am,

Bialik, and fellow intellectuals Yehoshua Rawnitzki

and Mordechai Ben Ami, who were all neighbors in Odessa, published an anonymous

manifesto in Hebrew, penned by Ahad Ha’am, which became a clarion call for

Jewish self-defense:

Brothers.… It is a disgrace for five and a half

million souls to place themselves in others’ hands, to stretch out their necks

and cry out for help, without trying to defend themselves, their property, and

the dignity of their lives. And who knows if it was not this disgrace of ours

that did not cause the start of our degradation in the eyes of all the people

and to turn us into the dirt in their eyes?… It is only he who knows how to

defend himself who is respected by others. If the citizens of this land had

seen that there is a limit, that we too, although we will not be able nor

willing to compete with them in robbery, violence, and cruelty, are nonetheless

ready and able to protect what is precious and sacred to us, until our last

drop of blood. If they had actually seen it, there is no doubt, they would not

have fallen upon us with such nonchalance; because then a few hundred drunkards

would not have dared to come with clubs and pickaxes in their hands to a large

community of Jews of some forty thousand souls to kill and to violently rob to

their hearts’ content. Brothers! The blood of our brethren in Kishinev cries

out to us: Shake off the dust and be men! Stop whining and begging, stop

reaching out to those who hate you and ostracize you, that they should come and

save you. Let your own hand defend yourself!18

Even after the Kishinev pogrom, Dubnow

retained his faith that the Jews could achieve a life of dignity and meaning as

a nation within the framework of social and cultural autonomy in the Diaspora,

in nation-states where they were a minority. He considered the Jews the

prototype for diaspora nations and formulated his own radical doctrine for

Jewish nationhood, writing:

When a people lose not only its political independence

but also its land when the storm of history uproots it and removes it far from

its natural homeland and it becomes dispersed and scattered in alien lands, and

in addition loses its unifying language; if, despite the fact that the external

national bonds have been destroyed, such a nation maintains itself for many

years, creates an independent existence, reveals a stubborn determination to

carry on its autonomous development, such a people has reached the highest

stage of cultural-historical individuality and may be said to be

indestructible, if only it cling forcefully to its national will.19

Thus the idea that the Jewish people’s mobility

strengthens and deepens its culture, and that non-territorial nationhood is the

pinnacle of moral achievement because it is unencumbered by borders and the

monopoly over the use of force has become a pet thesis for liberals and

internationalists.

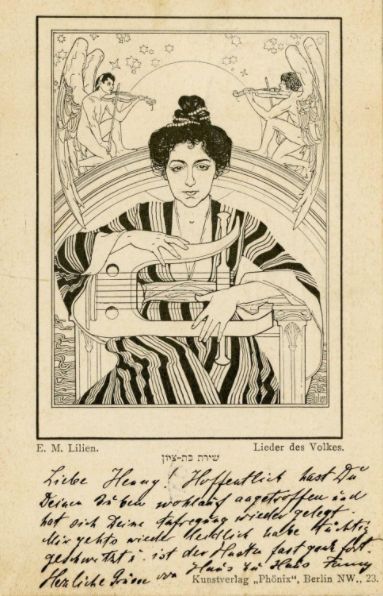

Letter in the handwriting of David Wolfson - on a

postcard with Lillien's work:

While the Hibat Zion movement was sending pioneers to

the Land of Israel, Dubnow opposed the Zionist

program of securing territorial sovereignty, deeming it impractical. Amid the

pogroms sparked by the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, he argued

that isolating the Jews in the backwater of Ottoman Palestine would degrade them

culturally and ethically, and they would “sink into Asiatic culture.” He wrote

to Moshe Leib Lilienblum, who had decided to join the

Lovers of Zion, that sovereignty was a “straw to clutch at, and those who grasp

at it will surely drown…in ignorance and barbarism.”20 He also disagreed with

his friend Ahad Ha’am’s idea that the Jews could establish a center of modern

life in Palestine. Dubnow maintained that from a

moral perspective, a diaspora national existence was preferable to an

exclusivist, territorial-sovereign nationhood, which would inevitably cling to

chauvinistic tribal nativism and state violence.

Dubnow’s adherence to the idea of diasporic autonomism was

rooted in his faith that Russia would one day become a liberal, multinational

state. This remained his opinion up until the Russian democrats surrendered to

the Bolsheviks during the 1917 Revolution.

In 1922, he took refuge in Berlin. Despite the failure

of the Jews to integrate into Soviet Russia and the early success of Zionism in

Palestine and the Balfour Declaration, Dubnow

continued to believe that the national future of the Jews lay in Europe. He

rejected assimilation as unnatural both psychologically and morally, and as a

threat to the Jewish people. Only a vibrant diaspora nation, united and

organized, without territorial sovereignty, could serve as the inspiration for

a progressive, pluralist, and multicultural society. Dubnow’s

vision was to build on the Jews’ proven success in keeping their ethnic

particularity, via their language, culture, and education, and their ability to

maintain national institutions. He wanted to revive the kahal system, but not

based on religious principles or hierarchy as it had been in the Middle Ages

and in the Russian Empire. The kahal he wanted to recreate would be of a

democratic-republican nature with a clearly secular national orientation. The

Jewish diaspora nation would serve as the model for multiethnic life in modern

states whose populations were not ethnically homogeneous and did not demand

assimilation into the predominant group.21

Even after the pogroms of 1903 and other upheavals, Dubnow believed Russia would become a multiethnic, liberal,

democratic country in which the Jews could flourish with

national/non-territorial autonomy. After the 1905 Revolution, when elections

for parliaments (Dumas) were first allowed, he played a key role in the

formation of the League for the Attainment of Full Rights for the Jewish People

of Russia. The goal of the league was “the realization in the full measure of

civil, political, and national rights for the Jewish people.” It organized as a

pressure group, not as a party, and mobilized Jewish voters to ensure “the

elections of candidates, preferably Jewish, who would strive for full rights

for the Jews and a democratic regime of Russia.”22

Indeed, many Russian Jews voted in the 1906 elections

for the liberal party, the Kadet, because of its

commitment to constitutional order and universal suffrage. Thousands of Jews

“who had previously no contact with political life were now drawn into it by

the exercise of their franchise. Russian Jews could feel as they had never felt

before that they had a stake in the future of Russia.”23

By the time the Bolsheviks seized power, almost all

Russian Jews, who were officially emancipated in the democratic 1917 February

Revolution, were anti-Bolsheviks. But when the Russian Civil War broke out and

anti-Bolshevik forces of the White Army committed anti-Jewish atrocities, many

Jews adopted the Bolsheviks as allies.24

As he saw fascism rising in Europe and the Jewish

national home in Palestine becoming a reality, Dubnow

still clung to his faith that the diaspora nation would be the dominant mode of

Jewish life, even if a Jewish state were to be established. He did not agree

that people must constantly strive for sovereignty to be a nation. Dubnow was murdered by a Latvian collaborator during the

Nazi occupation of Riga in 1941. For many, his cruel death became the symbol of

the disaster inherent in the naïve faith of living a secure Jewish life as a

scattered diaspora nation.

I created the Jewish State

Only after the appearance of Theodor Herzl on the

world stage did Palestine become a central focus of Jewish national sentiment.

He laid the ideological and organizational foundations for the Zionist

movement. His pamphlet Der Judenstaat (The Jewish

State, 1896) called for the massive evacuation of Jews from Europe and the

restoration of a Jewish state in the Holy Land. The Jewish State was a

prophetic document, preaching the ingathering of exiles as the solution to the

Jewish Question in Europe, and granting the Jews equal status among the

nations.25

Herzl provided concrete answers on how to transplant

Jews from Europe to Palestine, and how to build political and financial

institutions, schools, and settlements. A charismatic and relentless figure, he

traveled the capitals of Europe and beyond, building international backing of

imperial powers and alliances with other actors on the world stage. In many

ways, Herzl is the first modern Jewish statesman, who paved the way for

diplomacy in Israel both before and after statehood, and also for Diaspora Jewry.

In August 1897 Herzl presided over the First Zionist Congress in Basel,

Switzerland. After three days of remarkable deliberations, with hundreds of

enthusiastic Jewish delegates from seventeen countries in attendance, as well

as many non-Jews and European journalists, Herzl confided to his diary: “If I

were to sum up the Basel Congress in a single phrase, which I would not dare to

make public, I would say: in

Basel I created the Jewish State.”

1. S. Zeitilin, “The Council

of Four Lands,” The Jewish Quarterly Review 39, no. 2 (1948), 212.

2. Benjamin Pinkus, The Jews of the Soviet Union:

The History of a National Minority (Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet

Studies, Series Number 62),1988, 12.

3. Salo Wittmayer Baron, The Russian Jew under

tsars and Soviets, 1976, 112.

4. Pinkus, Jews of the Soviet Union, 16.

5. Benjamin Nathans, Beyond the Pale: The Jewish

Encounter with Late Imperial Russia (Studies on the History of Society and

Culture Book 45) Part of: Studies on the History of Society and Culture (17

Books), 2002, 34.

6. Ibid.

7. Charles King, Odessa: Genius and Death in a City of

Dreams (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2011), 97–106.

8. Louis Greenberg, The Jews in Russia: The

Struggle for Emancipation (Vol 1 & 2), 1987, 141.

9. Michael Stanislawski, “Why

Did Russian Jews Support the Bolshevik Revolution?” Tablet, October 25,

2017.

10. Jonathan Frankel, “The Jewish Socialism and the

Bund in Russia,” in The History of the Jews of Russia: 1772–1917, 255

11. Anna Geifman has noted

that in 1903 there were 136 million people in the empire, including seven

million Jews. See Anna Geifman, Thou Shalt Kill,

Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894–1917 (Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 1995), 32.

12. Simon Rabinovitch, “The

Dawn of a New Diaspora: Simon Dubnov’s Autonomism, from St. Petersburg to

Berlin,” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 50, no. 1 (January 2005), 270.

13. Charles E. Woodhouse and Henry J. Tobias,

“Primordial Ties and Political Process in Pre-Revolutionary Russia: The Case of

the Jewish Bund,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 8, no. 3 (April

1966), 331–360.

14. Zvi Gitelman, “The Jews: A Diaspora within a

Diaspora,” in Nations Abroad: Diaspora Politics and International Relations in

the Former Soviet Union, eds. Charles King and Neil Melvin (Boulder, Colorado:

Westview Press, 1998), 61.

15. Joshua M. Karlip, The

Tragedy of a Generation: The Rise and Fall of Jewish Nationalism in Eastern

Europe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 10.

16. Gitelman, “The Jews: A Diaspora within a

Diaspora,” 61.

17. Simon Dubnow, “Ahad

Ha’am’s Scroll of Mysteries (25 Years Since the Kishinev Massacre),” Hatekufah 24 (1934), 416

18. Ibid., 416–420

19. Rabinovitch, The Dawn of a New Diaspora:

Simon Dubnov's Autonomism, from St. Petersburg to Berlin August 2005 The Leo

Baeck Institute Yearbook 50(1):267-288281.

20. Miriam Frenkel, “The Medieval History of the Jews

in Islamic Lands: Landmarks and Prospects,” Peamim 92

(2002), 32.

21. After Dubnow wrote the

“Diaspora” entry in the Encyclopedia of Social Sciences in the 1930s, the term

“diaspora” became almost exclusively linked to the history of and political

sociology of the Jews.

22. Sidney Harcave, “Jews

and the First Russian National Election,” The American Slavic and European

Review 9, no. 1 (February 1950), 33–41.

23. Ibid., 41.

24. Michael Stanislawski, “Why Did Russian Jews

Support the Russian Revolution?,” Tablet, October 25, 2017.

25. Aharon Klieman, “Returning to the World Stage:

Herzl’s Zionist Statecraft,” Israel Journal of Foreign affairs 4, no. 2

(2010),76.

For updates click homepage here