By Eric

Vandenbroeck and co-workers

3 Nov. 2021: Back in Mach 2018, The New Yorker

published an article titled "Why Jewish History Is So Hard to Write"

the article, in particular, criticizes the two most common approaches to

writing Jewish history. Intrigued by this critique we decided on a third

approach.

The way to Zionism Part Two

From 1904 to 1914, the yishuv

in Palestine absorbed a significant wave of new migrants from Eastern Europe,

known as Second Aliyah. These newcomers emerged as the new social and political

elite that replaced the old, religious one with a modern revolutionary

vanguard. Zionist thought (and later historiography) glorified this olim,

stressing their mission and superior stature over the “simple” eastern European

Jews who migrated to the United States only to improve their lot. Historian Gur

Alroey wrote that Zionist historiography deliberately

downplayed the story of Jewish migration from Russia to the United States to

distinguish between the “uniqueness” of Jews who chose Palestine and the banal

masses who rushed to America with “no national purpose and its moral level was

undoubtedly lower than that of Aliya to Palestine.”1

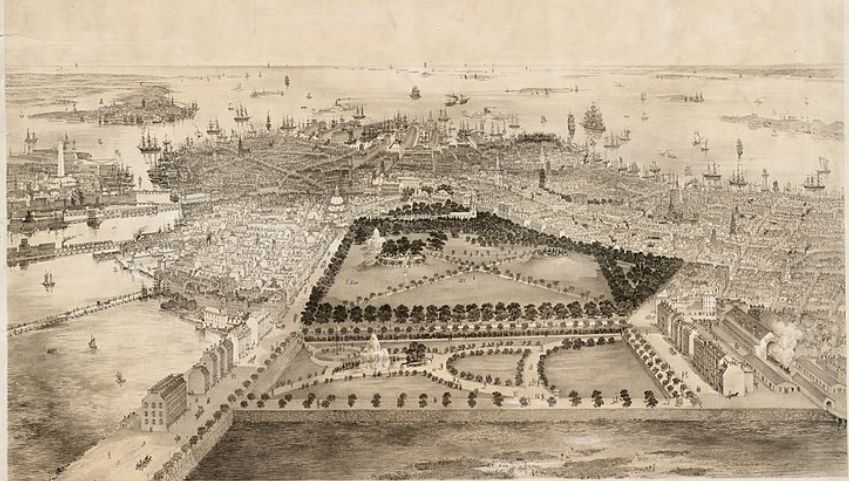

The USA and Boston as the 'New Jerusalem'.

Even after the Holocaust and the establishment of

Israel, America long remained the preferred destination of most Jews. Israelis

stigmatized them as pining for the fleshpots of Egypt, but Jews who arrived in

the United States rarely saw their move as a waystation on the road to their

ancient homeland. America was their new Promised Land, the “true Zion.”

Today, over seventy years after the establishment of

the State of Israel, there is no longer a real debate over which is the true

Jewish homeland. Even the most patriotic American Jews, who would never think

of uprooting themselves for a home overseas, understand that Israel is

increasingly the dominant force in the Jewish world and the only country that

can claim to be a homeland of the Jews.

America’s unique relationship with both the Jews and

the Hebraic heritage dates to before the nation’s founding. New England’s

Puritans of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries took great interest in the

Old Testament and Jewish history. They saw themselves as “the

new Israelites,” and Boston was often called “New Jerusalem.” They also

hailed the Hebrew language as “the mother of all languages,” and the earliest

Harvard presidents were Hebraists. But the Puritans were not Philo-Semites. In

fact, they rarely met Jews in their lives, and like other Christians, suspected

them of rejecting Christ. While Puritans prayed for mass conversion of the

Jews, they mistrusted the motives of individual converts who might be under the

spell of the Devil and, therefore, ready to backslide to “the prejudices of

their education.”2

The first Jews to set foot in America were Sephardic,

immigrating from Spanish and Portuguese domains in South America, the

Caribbean, and the Iberian Peninsula. The settlers who came from the Dutch

colony in Brazil to New Amsterdam in the 1650s were Sephardic as well; in 1654,

they founded Shearith Israel, the first Jewish

congregation in America, and the only synagogue in New York City until the

arrival of German Jews in the 1820s.

Jews also arrived in Rhode Island after the colony

declared in 1652 that “all men of whatever nation soever they may be…will have

the same privileges as Englishmen.” Though the purpose of the colony was “the

spread of Christianity,” and a 1663 Rhode Island law stated that “only

Christians can be admitted to the Colony,” in 1684, the Rhode Island

legislature decided that “Jews might expect as good protection as any stranger

being not of our nation.”

In 1762, when the Rhode Island Superior Court denied

naturalization to new Jewish arrivals, claiming that the colony was full, Ezra

Stiles, an eminent American theologian remarked: “Providence seems to make

everything work, for mortification of the Jews, and to prevent their

incorporation into any nation; that thus they continue as distinct people….

[It] forebodes that the Jews will never become incorporated with the people of

America, any more than in Europe, Asia, or Africa.”3 Stiles, who became the seventh

president of Yale (1778–1795), studied Hebrew regularly and was infatuated by

Jewish traditions. By 1768, Rhode Island’s Jews included twenty-five families,

and of the 2.5 million colonists in 1776, Jews were a negligible minority,

numbering around 2,000.

Throughout the nation’s first decades, Jews in the

United States made every effort to make their adopted country their new

homeland. In fact, those who called for Jewish salvation in Palestine in the

early years of the republic were invariably Christians.

On the morning of October 31, 1819, a large crowd crammed

into the Old South Church in Boston to hear a young priest named Levi Parsons.

He told his congregation that the Jews had “taught us the way to salvation,”

and it was the Christians’ mission to restore them to their ancient homeland.

He urged his flock to become missionaries in the Holy Land and prepare the

ground for the return of the Jews, who in turn would welcome the second coming

of Christ. Thus, the Jews would inaugurate the “millennial age of peace and

spiritual solidarity,” and all would recognize the sovereignty of Christ.4

It is often little understood in Jewish circles

the extent to which Christian Zionists in the United States consider the

existence and fate of the Jewish state a critical component of their own

identity. Everyone knows that Israel depends on the United States as a

superpower patron; less well known is that Israel has a profound impact on the

character and identity of America itself. How did it happen that the internal

debate about American values, culture, heritage, and international mission is

shaped by what goes on in faraway Israel?

From its inception, American Jewry developed and

defined itself in light of changes in American identity and the United States’

place in the world. In the early nineteenth century, the country was still an

ethnic nation-state, based mainly on an Anglo-American Protestant culture, with

more than a dash of race and religion. It conceived of itself as a Christian

country that was fulfilling the ancient Israelites’ dream of living in the

Promised Land, with the Hebrew Bible as its guide.

The small number of Jews who lived in the United

States tried to fit into this Protestant paradigm. They were relatively

invisible until the arrival of a large group of German Jews in the 1840s, who

“got along very well with their non-Jewish neighbors, although American

conception of Jews in the abstract at no time lacked the unfavorable elements

embedded in the European tradition.”5 German-Jewish immigrants spread rapidly

throughout the United States, creating the communal and religious structures

that would form the backbone of American Jewry and making every effort to be

part of the American “chosen people.” Inspired by the Jewish Reform Movement

they had imported from Germany, these immigrants worked to replace Orthodox

Judaism, which they saw as too tribal and trapped in ritual and theology, with

a universal code of morality.

The immigration of German Jews came against a backdrop

of larger mass immigration. The population of the United States ballooned

between 1815 and 1860, when some five million immigrants arrived from Europe,

particularly from Ireland, Britain, and Germany. According to the 1860 census,

there were over 31 million people in the United States. This period witnessed

increasing hostility from Protestant Americans against Catholics, many of whom

were refugees from the Irish Potato Famine. The Jews were, at this juncture, a

drop in the ocean, but they started to organize. As early as 1840, when the

United States was already home to 15,000 Jews, the community rallied to

pressure President Martin Van Buren to intervene in the Damascus blood libel

affair.6

By the eve of the 1860 presidential election,

after an influx of thousands of immigrants from Germany, the number of Jewish

US citizens had risen to 50,000. Their leaders started to organize as a

nationwide lobby group to protest the abduction of Edgardo Mortara, a

Jewish-Italian boy kidnapped by the Vatican in 1858 after a family servant

claimed that she had secretly baptized him. The incident profoundly shocked

liberal society across Europe and caused shockwaves in the American Jewish

community. Anti-Catholic sentiment in the United States no doubt helped the

Jews to find sympathy for their protests against Catholic abuses of Jews in

Europe and the Middle East, and they rode this wave.7

It was around then that Abraham Jonas, a close Jewish

friend to future president Abraham Lincoln, started recruiting Jews to the

Republican Party, having despaired of receiving help in the Mortara case from

President James Buchanan, a Democrat, and Secretary of State Lewis Cass.

Despite the antebellum Republican Party’s nativist trends, which targeted Jews

and other foreigners, Illinois Representative Abraham Lincoln swam against the

tide and passionately decried not only slavery but also anti-Semitism. In a

speech in New York in 1859, he declared:

I know of no distinction among men, except those of

the heart and head. I now repeat that, though I am native-born, my country is

the World, and my love for man is as broad as the race and as deep as its

humanity. As a matter of course I include native and foreign people, Protestant

and Catholic, Jew and Gentile.8

Nevertheless, during the Civil War, some states

forbade Jews from holding public office and anti-Semitism was in the air.

General Ulysses S. Grant accused the Jews of being “unprincipled.” He refused

them permits to come South, forbade his officers from allowing them to move

with the army, and even expelled all the Jews from his military district in

1862. “They come in with their carpet-sacks in spite of all that can be done to

prevent it,” he complained.9

When he was elected president after the war, Grant

publicly apologized to the Jews, but some would argue that his anti-Semitic

legacy had still not entirely disappeared from the ranks of the US

Army.10

Two decades after the American Civil War and Lincoln’s

assassination, the United States was home to some 250,000 Jews. As the country

expanded westward, it was flooded with some 30 million immigrants from southern

and eastern Europe: Italians, Poles, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Russians, and

of course, Jews. They changed the face of the United States, which by the late

nineteenth century became a multiethnic, pluralistic country.

The anti-Semitic violence that erupted in the Russian

Empire after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 prompted a mass

exodus of Russian Jews. From 1880–1914, some 2.5 million abandoned the Pale of

Settlement. In 1880, New York City was home to roughly 80,000 Jews; by 1910,

there were 1.1 million; and by 1920, their numbers had risen to 1.5 million, or

more than 30 percent of New York’s population. In 1927, the number of Jews in

the United States hit 4.2 million.

The American Jewish Community

The young Zionist leader Haim Arlosoroff

visited the United States from Palestine several times between 1926 and 1928

and recorded his impressions of American Jewry’s meteoric development in a

series of fascinating letters. He saw it as a unique historical experiment,

which had no parallel with any model of Jewish existence throughout history and

could not be explained in terms borrowed from western and eastern European

experiences. He wrote that American Jewry was the most important phase in

Jewish history since the Second Temple era and could even be seen as a

messianic miracle. He described the “overnight” emergence of American Jewry as

“a finger of God in our national life” and a “beacon for all Jews.”11

Initially, this mass influx of eastern European Jews

caused a split within American Jewry. Jewish politics were also revolutionized,

reorganizing around hundreds of lands- mannschaften,

mutual aid societies set up to help Jewish immigrants from specific eastern

European towns to integrate into American society.12 The wealthy German Jews

were anxious lest an influx of poor, traditional eastern European Jews, the

alien hordes, impinge their status as veteran members of society.13 They also

feared the arrival of the Zionist national spirit imported by Russian Jewish

supporters of Hovevei Zion, which would surely sully

their reputations as patriotic Americans. The descendants of German Jewish

immigrants, who affiliated with the Reform Movement, wanted to put an end once

and for all to the incessant questions about their national loyalty. In 1885,

they adopted the Pittsburgh Platform, which declared that the Jews were “no

longer a nation, but a religious community.”14

Meanwhile, millions of Jewish immigrants from eastern

Europe sidelined their “aristocratic” German-born brethren. They built a

vibrant Yiddish subculture, established Jewish schools and kosher restaurants,

opened Jewish summer camps, choirs, and theater troupes, and developed a vast

literature and press, which dwarfed the Jewish institutions from western

Europe. This was all accompanied by radical working-class politics. Left-wing

Jews, who arrived as part of the massive wave of immigration in the 1880s, bolstered

the more radical forces and became a powerful branch of the global Left and

arguably influenced the Jewish revolutionaries in the Russian Empire.

Nevertheless, as Arlosoroff wrote, eastern European

Jews “were washed in a stream of forceful Americanization, which could neither

be stopped nor glossed over.”15 While liberal Jews in America were still

recoiling from the rumblings of early Zionism, the country also witnessed the

emergence of early Christian Zionism. In the late nineteenth century, evangelical

leader William E. Blackstone secured the signatures of more than 400 members of

the American elite, including Supreme Court justices, senators, businessmen,

and journalists, to pressure President Benjamin Harrison to promise the return

of the Jews to their historic homeland. In his 1878 book Jesus is Coming,

Blackstone wrote that the second coming of Christ depended on the ingathering

of the Jews in the Land of Israel. That is, the Jewish people’s homecoming and

the restoration of their sovereignty were critical stages in the Christian

messianic vision of the End of Days. Blackstone visited Zionist pioneering

communities in the Land of Israel in the 1880s and raised funds for the

settlers. In many senses, he laid the foundations for the enduring bonds

between evangelical Christianity and Zionism. Many liberal Jews today would be

surprised to learn that Louis Brandeis, the father of liberal Jewry, hailed

Blackstone as “a Father of Zionism.”16 Perhaps counterintuitively, liberal

American Jewry was tied at its inception to evangelical Zionism.

Born in 1856 in Louisville, Kentucky, to an

assimilated family, Brandeis had little connection to Jewish heritage. Over the

years, he became increasingly vocal about his identity and ultimately

articulated a vision of symbiosis between American Jews’ commitment to Zionism

and their commitment to America. “Loyalty to America demands that each American

Jew become a Zionist,” he said. “To be good Americans, we must be better Jews,

and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists.”17 This mantra eventually became

the moral basis of the bond between liberal American Jewry and the State of

Israel, which resonates even today.

As a young lawyer of repute, Louis

Dembitz Brandeis (who later had a University named after him) was

initially quiet about his Jewish identity and happy to go along with the

Puritanical vision of America as the Holy Land and white evangelicals as the

newly chosen people. Historian Jonathan Sarna writes that Brandeis “grew up to

share his mother’s distaste for formal religion; and…fulfilled her hopes for a

character formed by a ‘pure spirit and the highest ideals.’’’18

As a young man, Brandeis established a special

bond with his brother-in-law, Felix Adler (1851–1933), who had come to America

from Germany as a boy. His father, Samuel Adler, moved his family to New York

City to become the rabbi of the Reform Temple Emanu-El, and Felix later went

back to Germany to take doctoral studies. After his return to the United

States, he championed a doctrine he called “The Judaism of the Future” and

launched the “ethical culture movement,” which had a little trace of God-centered

religion. This doctrine won over many followers, but among even progressive

Jews, many felt that Adler has emptied their Jewish identity, and he came to be

seen, according to one historian, “as a dangerous threat to the seemingly

stable nature of the American Jewish community.”19

Brandeis himself was also a humanist. He saw a deep

connection between Protestant ethics and the heritage of the Hebrew prophets.

Yet for him, the employment of Jewish heritage as a universal democratic creed

should not come at the expense of cultivating Jewish uniqueness. As he came to

appreciate the life of eastern European immigrants, he concluded that American

Jews should not assimilate, but thrive as an ethnic community by strengthening

their own kinship ties and connecting tribal tradition to the cultural and

intellectual heritage of the United States. They could do so by devoting

themselves to the cause of Zionism.

Indeed, the idea that Herzl’s Zionism should be an

integral element in Jewish American identity only appeared

after the First Zionist Congress in 1897. It was Richard James Horatio Gottheil, a professor of Semitic languages at Columbia

University and the president of the American Zionist Federation from 1898 to

1904, who formulated the thesis that Herzl’s Basel Plan spoke only about a

national home and not a state and thus could fit harmoniously with the

aspiration of American Jews without exposing them to charges of dual loyalty.20

In 1905, Brandeis, already a well-known lawyer,

experienced a profound identity shift and publicly professed his Judaism for

the first time. Although he implored his Jewish brethren to refrain from

defining themselves as “hyphenated Americans,” he encouraged them to remold

their communities and religious-cultural heritage in the spirit of American

democracy. In so doing, writes Allon Gal, Brandeis gave a stamp of approval to

“clear ethnic politics.”21

Jewish artists and intellectuals played a central role

in shaping the discourse over American identity and the place of ethnic groups

in the new American patchwork. Consider the play The Melting Pot by the

Russian-born Jewish playwright Israel Zangwill, which opened on Broadway in

1908. It tells the story of a young composer, David, who arrives in New York

from Russia and composes a symphony celebrating the city’s ethnic harmony. He

dreams of marrying a beautiful Christian girl, unencumbered by his Jewish identity:

America is God’s crucible, the great Melting-Pot where

all the races of Europe are melting and reforming!... Here you stand with your

fifty groups, with your fifty languages…and your fifty blood hatreds…into the

Crucible with you all! God is making the great American.

In the climactic scene, the young composer stands with

his beloved Vera on a Lower Manhattan rooftop, with the Statue of Liberty

gleaming in the distance, and excitedly points to the metropolis below. “There

she lies, the great Melting-Pot, listen! Can’t you hear the roaring and the

bubbling?... Celt and Latin, Slav and Teuton, Greek and Syrian, black and

yellow,” Vera cuts him off and whispers back: “Jew and Gentile.”22

Zangwill’s play won critical acclaim across America.

When it was staged in Washington, DC, President Theodore Roosevelt called out

from his box: “That’s a great play, Mr. Zangwill, that’s a great play.”

Zangwill himself was married to a Christian woman. Although he backed the idea

of a Jewish state after meeting Herzl in 1895, he did not think that it had to

be in Palestine. He imagined a safe haven for the Jews along the lines of New

Zealand or Australia, namely as “a large Jewish colony under the protection of

the British Crown.”23

His play was panned by Jewish critics for giving a

green light to assimilation, and indeed, the philosophy of the melting pot

became the intellectual basis for an aggressive policy of Americanization,

which erased immigrants’ connections to their original countries and native

cultures.24

It did not take long, however, before the idea of the

melting pot became the ethos of American Jewry. The Jews embraced the patriotic

vision of America as the newly chosen people perhaps more enthusiastically than

any other European immigrants, despite being the only non-Christian group. They

felt that perhaps for the first time ever, their religion and ethnic identity

were tolerated, notwithstanding minor bursts of anti-Semitism. Jewish artists

and intellectuals, who became the leading theoreticians and drivers of the

emerging American identity, combined their ethnoreligious identity with an

ethos of American patriotism. At the outset, major organizations, including the

American Jewish Committee, B’nai B’rith, and the American Jewish Congress,

modeled themselves as all-American, cosmopolitan institutions that stressed

their loyalty to America in conjunction with their promotion of universal human

rights.

One Russian-Jewish immigrant, Mary Antin, described

George Washington and other founding fathers as “our forefathers” and said of

the United States: “The country was for all citizens, and I was a citizen, and

when we stood up to sing ‘America!’ I shouted the words with all my might.”25 Her

choice of the words “our forefathers” incensed some American Protestants, who

stubbornly saw the Jews as foreign implants. When Jewish anarchist Jacob Abrams

was tried for sedition in 1914 and invoked in his defense “our forefathers of

the American Revolution,” the judge incredulously interjected to ask whether he

meant to refer to “the founders of this nation as your forefathers” and asked

him bluntly: “Why don’t you go back to Russia?”26

During World War I, suspicions arouse about American

Jews’ dual loyalties because of their ties to Germany. Americans also

questioned the Jews’ loyalties because of their communal institutions and

transnational attachments to European Jewry and Zionism, a separatist national

movement.

Most spokesmen for American Jewry eagerly lauded

American nationalism as their civic identity, but in 1915, Horace Kallen, a

German rabbi’s son, assailed Zangwill’s vision of the melting pot in an

influential essay titled “Democracy Versus the Melting Pot.” He argued that

Zangwill’s representation of American life was inaccurate, and the melting pot

was a poor vision for it. In its place, Kallen proposed cultural pluralism.

Instead of erasing ethnocultural differences between groups in American

society, this diversity, including Jewish identity, should be cherished as an

asset in the cultivation of a vibrant democratic society. In his vision, the

United States would be a diverse federation of minorities inspiring each other

and coexisting under the banner of civic loyalty to the institutions of

American democracy. Only cultural pluralism, Kallen argued, would guarantee the

country’s national resilience.

World War I aggravated the debate about loyalty and

identity in America. To begin with, wars always demand unwavering loyalty and

bind citizens to their country through the ultimate sacrifice. The war also

raised uncomfortable questions about immigrants’ loyalties to their countries

of origin, especially if those countries were at war with the United States.

Some 250,000 Jews enlisted in the US Army; some 3,500 of them were killed in

battle. However, once Americans started suspecting dual loyalties on the part

of German immigrants, including Jews, many started seeing Kallen’s vision of

cultural pluralism as a threat to the American nation.

Kallen was not alone in his beliefs. In 1916, a

radical young journalist named Randolph Bourne published an article in which he

feted America as a transnational nation of cultural affinities to diverse home

countries. He slammed the vision of America as an isolationist Anglo-Protestant

nation, and his essay “Trans-National America” would also enter the canon of

texts about American identity.27

That same year, American philosopher John Dewey

denounced those who spread fear about immigrants’ ties and loyalties to their

home countries. He argued that “such terms as Irish-American or Hebrew-American

or German-American are false terms,” because they presupposed that America was

a static entity “to which other factors may be hitched on.” However, “the

typical American is himself a hyphenated character…he is international and

interracial in his make-up.”28

This internationalist pluralism cut against the winds

of nationalism that swept through America in the early twentieth century.

Americans were already deeply suspicious of and hostile towards second-and

third-generation “aliens,” and their suspicions were only heightened during the

war. President Woodrow Wilson said: “You cannot become thorough Americans if

you think of yourselves in groups. America does not consist of groups.” He

added that those who regarded themselves as “belonging to a particular national

group in America” were not worthy “to live under the Stars and Stripes.”29

American Jews during World War I watched the unfolding

disaster wrought on their kin in eastern Europe with horror, as the Jews fell

hostage and victim to the warring sides. The Russians treated the Jews of

Eastern Europe as a fifth column; in spring 1915, they cruelly expelled more

than half a million Jews from the area of the front against Germany and

Austria-Hungary. When the Russian army retreated, it slaughtered masses of Jews

in Poland and eastern Galicia, torching dozens of villages with their inhabitants

inside. Eastern Europe became “a physical and spiritual graveyard for Jews,” in

the words of historian Aviel Roshwald, who has

documented how they fell prey to the Russians and Germans alike. The Germans

conquered vast swathes of Russian territory at the start of the war and

operated a slick propaganda campaign that promised the Jews liberation from

tsarist oppression but still treated them as treasonous dirt. Many Jews

suffered under the yoke of anti-Semitism and were dispatched for hard labor in

what were effectively concentration camps.30

Many American Jews had families trapped in the carnage

in eastern Europe, and news of the devastation spurred them into establishing

aid organizations that sent money, personnel, and supplies to Russia and

Poland. This mission gave birth to the modern network of American-Jewish

international aid organizations, including the American Jewish Joint

Distribution Committee, which still provides humanitarian aid to distressed

populations around the world.31 Thus, while the Jews of eastern Europe suffered

acute persecution, their brothers and sisters who had sailed to safety in

America grew stronger as a community. Indeed, America gave the Jews of eastern

Europe a safe haven and fertile soil on which to express their Judaism. They,

in turn, cherished the United States as a national home with an open democratic

society and free-market ethos. America allowed them to be patriots while

enjoying a Jewish religious and cultural renaissance. With the “Jewish

Question” no longer a serious worry, the Jews were able to focus on securing

their place in American society and politics. The United States’ role as the

undisputed new Jewish homeland made American Zionists a marginal factor within

both American Jewry and the Zionist movement, a few of them intended to

personally fulfill Herzl’s vision and move to the Land of Israel. There was no

need for Zionism in the United States; the Jews believed that they had cracked

Herzl’s dilemma of how they could live in peace. In the words of historian

Robert Wiebe: “What could Zionism, a wandering minstrel of a movement, offer

them?”32

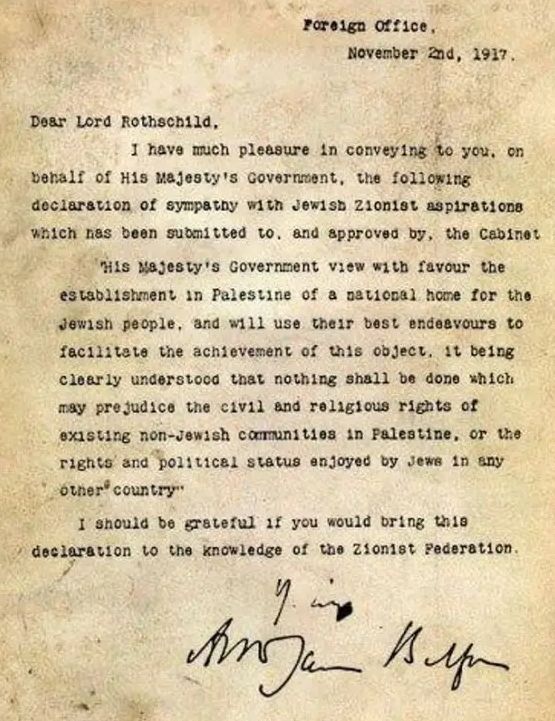

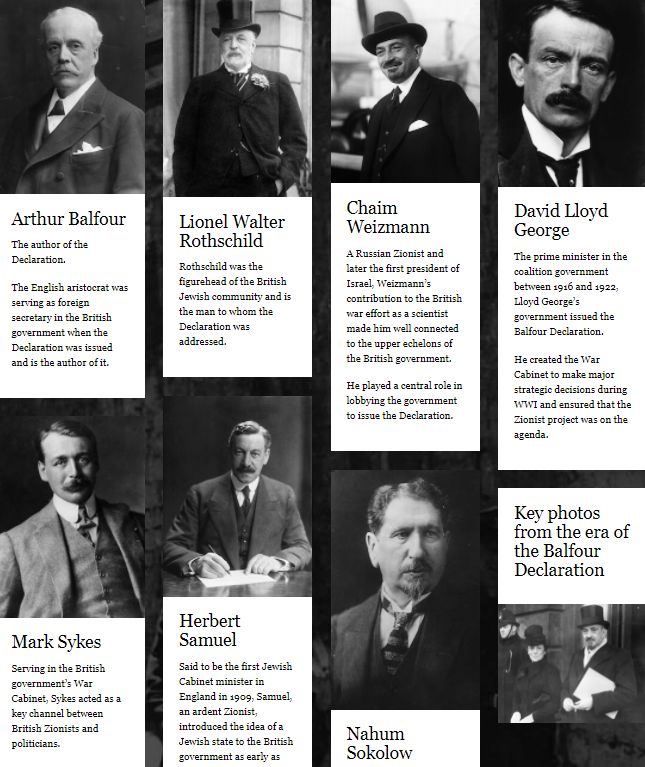

The

Balfour Declaration

Louis Brandeis, Woodrow Wilson, and the Balfour

Declaration World War I precipitated the collapse of mighty empires and thrust

the question of national self-determination to the fore. In so doing, it

compelled American Zionists to reconsider their attitude toward Jewish

nationalism. In June 1914, Louis Brandeis assumed the leadership of the

Provisional Executive Committee for Zionist Affairs. He backed Zionism out of

an understanding that the evolving American identity had to be made amenable to

Jewish ethnic identity, and he saw Zionism as a means with which to strengthen

American-Jewish identity. He believed that American Jews needed to connect to

their national roots to form a coherent group based on more than liberal

religion and guarantee that Judaism did not dissipate into the broader American

population, but rather constituted a meaningful part of it.

According to historian Jonathan Sarna, Brandeis’s

personal charm and public reputation gave Zionism tremendous momentum in the

United States. Many American Jews joined the ranks of the Zionist movement, and

its coffers grew fuller than ever. The fact that a man of Brandeis’s stature

backed it gave more public legitimacy after he was appointed the first Jewish

associate justice of the US Supreme Court in 1916. His support induced other

famous Jews to declare their support for Zionism as the framework through which

they could reconcile their universalist, progressive ideals with their latent

Jewish identity. Thanks to Brandeis, Zionism became something of a civic

religion for secular American Jews, a religion that aspired, in Sarna’s words,

to create “a model state in the Holy Land, freed from the economic wrongs, the

social injustices and the greed of modern-day industrialism.”33

By cultivating a synthesis between loyalty to America,

loyalty to the Jewish people, and a commitment to the notion that the Jews

deserved an independent polity, Brandeis encouraged Reform Jews, who considered

Judaism to be just a religion, to mellow their opposition to Zionism.34 His

earnest desire to assist the Zionist movement, even from afar, made him a

central player in promoting the Jewish nation-building project in Palestine

under President Wilson’s administration.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Wilson took a

defensive line and kept the United States out of the fighting. In time,

however, he set his sights on replacing the imperial world order with one based

on the “universal principles of liberty and justice through institutionalized

international cooperation.”35 The US entry into the war on April 6, 1917, the

collapse of the Ottoman empire, and the impending British takeover of Palestine

energized the Zionist diplomatic campaign for British support for a Jewish

national home. On April 21, 1917, Zionist philanthropist James de Rothschild,

together with the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, asked Justice Brandeis to

secure President Wilson’s approval for Britain’s plans for Palestine in a

telegram:

Unanimous opinion [is that the] only satisfactory

solution [is a] Jewish Palestine under British protectorate. Russian Zionists

fully approve. Public opinion and competent authorities here [are] favorable.…

It would greatly help if American Jews would suggest this scheme before their

Government.36

Upon receiving this appeal, Brandeis and his American

Zionist colleagues started lobbying the president. Brandeis met President

Wilson on May 6, 1917, and argued that a Jewish state would fulfill the

conditions of the type of peace settlement he envisaged, as well as replace

Ottoman tyranny with a democratic state in which the Jews, an oppressed

minority, would be able to freely pursue their cultural and economic

development. Brandeis also met British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour.

Wilson endorsed the idea of a Jewish national home in

Palestine not just because it matched his commitment to self-determination (as

listed in his famous Fourteen Points of January 1918), but also for internal

political reasons, namely the Jewish vote. Zionism spoke to Wilson’s heart, and

his religious faith propelled him to accept the Balfour Declaration, the first

formal recognition by the British government of Jewish national rights in

Palestine.

Although President Wilson saw himself as a historic

partner in the restoration of the Jews to their homeland, he still wavered

about alienating Ottoman Turkey as a potential ally.37 Only after the defeat of

the Ottoman Empire did he publicly declare his support for the establishment of

a Jewish national home in Palestine, and in January 1918, Congress adopted its

own resolution supporting a Jewish Commonwealth in Palestine.

An intensive campaign of Jewish diplomacy ensured that

the historic declaration was enshrined in the Paris Peace Conference. The

Balfour Declaration also became part of the preamble of the League of Nations

mandate, acquiring full legal standing in international law. The Allied powers,

the league announced, made Britain “responsible for putting into effect the

declaration originally made on November 2, 1917, by the Government of his

Britannic majesty, and adopted by the said Powers.”38

Martin Kramer has written that the Balfour Declaration

is justly considered the beginning of the Jewish nation-state’s legitimation by

other nations, and therefore a subject of attack by Israel’s enemies. However,

while in the collective memory of American Jewry the declaration was secured by

Louis Brandeis and President Wilson, Zionist historiography and Israel’s

collective memory remember Chaim Weizmann as the genius behind it. After the

declaration was issued, the leader of Revisionist Zionism, Ze’ev Jabotinsky,

said: “The declaration is the personal achievement of one man alone: Dr. Chaim

Weizmann.… In our history, the declaration will remain linked to the name of

Weizmann.”39

Weizmann, who became Israel’s first president in 1949,

grew up in the Russian shtetl with deep roots in Jewish tradition, but outgrew

his East European mentality to become “an Englishman.” After moving to Britain

in 1904, he earned a great reputation as a biochemist who developed the

acetone-butanol-ethanol fermentation process, yet his true passion lay in

Zionism. He used his professional success and prestige to climb the ladder of

the Zionist movement, which had been thrust into turmoil by the sudden death of

Herzl in 1904. He gained prominence as a British Zionist activist and used his

celebrity status among Britain’s elite to raise money and support to build a

university in Palestine. In 1921, Weizmann conquered American Zionism as well,

effectively staging an organizational coup with Brandeis’s American rivals, who

removed Brandeis from his leading position of the American Zionist

Organization. According to historian Ben Halpern, Weizmann defined Zionism as

“Palestine first” and believed that Brandeis and his allies “were not Jewish

nationalists at all.”40

As a man who could bridge eastern and western Europe,

he understood that he needed American Jewish support more than anything else.

“They can give up on us, but we cannot give up on them,” was his mantra

regarding American Jewry.

Only 60,000 Jews lived in Palestine in 1918, while the

population in America was growing by leaps and bounds. Prominent non-Zionist

American Jewish leaders, including Louis Marshall and Cyrus Adler, had feared

that supporting Zionism would raise allegations of dual loyalties, but Wilson’s

statement enabled them to retroactively endorse the Balfour Declaration.41 Soon

after it was signed, Marshall conceded that “to combat Zionism at this time is

to combat the Government of England, France, and Italy, and to some extent our

Government in so far as its political interests are united with those of the

nations with which it has joined in fighting the curse of autocracy.”42

Marshall became a critical partner of Chaim Weizmann

in raising funds among American Jews for the Zionist project in Palestine.

However, he and his colleagues at the American Jewish Committee refused to

endorse Palestine as a national home for the Jewish people at the same time,

making do with supporting a “center for Judaism.” They insisted that “the Jews

of the United States have established a permanent home…and recognize their

unqualified allegiance to this country.” For them, this was axiomatic. They also

insisted that Jewish citizens of other democratic countries would continue “to

live…where they enjoy full civil and religious liberty.” Although they

acknowledged that many Jews were moved by a traditional yearning for the Holy

Land, they limited their support to a “center for Judaism…for the stimulation

of our faith…and for the rehabilitation of the land,” and decidedly not for an

independent national polity. This remained the official position of the

American Jewish Committee until the eve of World War II.43

Indeed, Weizmann invented the remarkable formula that

allowed the alliance between Palestinian Zionists and American Jews to advance

the cause of Jewish nationalism in the twentieth century by collaborating with

Louis Marshall. That formula, which he labeled “shared duty and mutual

responsibility,” meant the following division of labor: we in Palestine will

give our sweat and blood, and you, our brothers and sisters in America, will

give your financial resources and political support. After the establishment of

the State of Israel, the AJC gradually became the most important diplomatic

organization among Diaspora Jewry, working to safeguard the security and

international standing of Jews worldwide and in the State of Israel.44

Identification of the Jew with the United States

The stronger the Zionist movement grew, the more strongly

American Jews also identified with the United States. American Zionists did

their utmost to avoid accusations of dual loyalties or a lack of patriotism.

Even during the Holocaust, when the Jews of Europe desperately needed their

help, American Jews took little public action, out of fear of undermining their

standing as loyal Americans. In his book The Abandonment of the Jews, David

Wyman documented how American Jews chose to champion American interests during

the war at the expense of saving European Jewry.45 This raises the disturbing

question: Did this excessive loyalty to President Franklin D. Roosevelt allow

him to ignore the genocide of the Jews as a factor in weighing US

interests?

However, the battle to defeat fascism in Europe also

opened the door for American Jews to at long last harmonize Jewish values with

universal American values. In her research on American-Jewish soldiers during

and after World War II, historian Deborah Dash Moore showed how the war

provided Jews an entry ticket to American society. White Anglo-Saxon America,

which the Jews had never been a part of, now had one supreme mission: to fight

for freedom and crush fascism. Ironically perhaps, while the Jews of Europe

were being incinerated in the name of the Nazis’ vision of racial purity, the

Jews of America were offered a golden opportunity to prove their allegiance to

the American spirit, to make anti-Semitism and anti-Jewish discrimination

unacceptable, and to secure complete social integration. This process

effectively transformed them into members of white society and faithful

adherents of the American creed that embraced Catholics and Protestants,

emphasizing their liberal common ground over religious differences.

1 Gur Alroey, An Unpromising Land: Jewish Migration to Palestine

in the Early Twentieth Century (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014),

2017.

2 Milton M. Klein, “A

Jew at Harvard in the 18th Century,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts

Historical Society 97 (1985), 135–145.

3 Oscar Reiss, The

Jews in Colonia America (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2000), 49.

4 Michael Oren,

Power, Faith, and Fantasy: America in the Middle East, 1776 to the Present (New

York: W. W. Norton, 2007), 80–81.

5 John Higham,

“Social Discrimination Against Jews in America, 1830–1930,” American Jewish

Historical Society 47 (September 1957), 3.

6 Alexander DeConde, Ethnicity, Race, and American Foreign Policy

(Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992), 52.

7 David I. Kertzer,

The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara (New York: Vintage Books, 1998), 125–127.

8 Jonathan D. Sarna

and Benjamin Shapell, Lincoln and the Jews: A History

(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015), 46.

9 Joseph Lebowich, “General Ulysses S. Grant And The Jews,”

Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 17 (1909), 71–79.

10 Joseph W

Bendersky, The “Jewish Threat”: Anti-Semitic Politics of the U.S. Army (New

York: Basic Books, 2000).

11 Haim Arlosoroff, “New York and Jerusalem” (letter 5 in “Letters

on American Jewry), Hatekufah 26–27 (1930), 466–467

[Hebrew].

12 Daniel Soyer,

Jewish Immigrant Associations and American Identity in New York: 1880–1939,

(Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2001), 49–81.

13 In his bestselling

book about eastern European Jews’ impact on American Jewry, Irving Howe recalls

how in 1908, New York Police Department Commissioner Theodore Bingham claimed

that 50 percent of criminals in New York City were eastern European Jews, calling

them “burglars, firebugs [arsonists], pickpockets and highway robbers, when

they have courage.” See Irving Howe, World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the

East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made (New York: New

York University Press, 2005), 127.

14 “The Pittsburgh

Platform (1885),” Central Conference of American

Rabbis, https://www.ccarnet.org/rabbinic-voice/platforms/article-declaration-principles/.

15 Arlosoroff, “New York and Jerusalem,” 476 [Hebrew].

16 Timothy P. Weber,

On the Road to Armageddon: How Evangelicals Became Israel’s Best Friends (Grand

Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2004) 106.

17 Louis Brandeis, On

Zionism (Washington, DC: Zionist Organization of America, 1942), 11, 49–50.

18 Jonathan D. Sarna,

“The Greatest Jew in the World Since Jesus Christ: The Jewish Legacy of Louis

D. Brandeis,” American Jewish History 81, no. 3/4 (Spring/Summer 1994), 347.

19 Benny Kraut, From

Reform Judaism to Ethical Culture: The Religious Evolution of Felix Adler

(Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1979), 107.

20 Zohar Segev,

“European Zionism in the United States: The Americanization of Herzl’s Doctrine

by American Zionist Leaders-Case Studies,” Modern Judaism 26, no. 3 (October

2006), 279.

21 Allon Gal, “Louis

Brandeis and American Zionism,” in The Legal and Zionist Tradition of Louis D.

Brandeis, ed. Allon Gal (Jerusalem: Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2005), 62

[Hebrew].

22 Arthur M.

Schlesinger, The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society

(New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1992), 32–33.

23 Mira Yungmann, “Zangwill versus Herzl and Pinsker: Three

Approaches to the Jewish Problem,” in Proceedings of The Eleventh World

Congress of Jewish Studies part 2, vol. 2 (Jerusalem: World Congress of Jewish

Studies, 1993/1994), 171–177 [Hebrew].

24 President

Roosevelt himself used the metaphor of the “crucible” when he said: “We can

have no ‘fifty-fifty’ allegiance in this country. Either a man is an American

and nothing else, or he is not an American at all.” See Schlesinger, The

Disuniting of America, 32–35.

25 Lawrence H. Fuchs,

The American Kaleidoscope: Race, Ethnicity, and the Civic Culture (Hanover NH:

Wesleyan University Press, 1990), 67–68.

26 Ibid.

27 Ralph Bourne,

“Trans-National America,” The Atlantic, July

1916, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1916/07/trans-national-america/304838/.

28 Nathan Glazer, We

Are All Multiculturalists Now (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997),

86.

29 DeConde, Ethnicity, Race, and American Foreign Policy, 83.

30 Aviel Roshwald, “Jewish Cultural Identity in Eastern and Central

Europe during the Great War,” in European Culture in the Great War: The Arts,

Entertainment and Propaganda 1914-1918, eds. Aviel Roshwald

and Richard Stites (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 89–126.

31 Sarna, American

Judaism, 210–211.

32 Robert H. Wiebe,

Who We Are: A History of Popular Nationalism, (Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 2002), 35–36.

33 Sarna, American

Judaism, 204–205.

34 Brandeis’s Zionism

must be understood in the context not just of the plight of Jews in eastern

Europe but also the struggle over American-Jewish identity. Brandeis and his

American Zionist colleagues were only distantly involved in the Jewish state-building

project in Palestine and to a large extent were “armchair Zionists.” See Gal,

“Louis Brandeis and American Zionism,” 70–71 [Hebrew].

35 Erez Manela, “The

Wilsonian Moment and the Rise of Anticolonial Nationalism: The Case of Egypt,”

Diplomacy and Statecraft 12, no. 4 (December 2001), 102.

36 Richard Ned Lebow,

“Wilson and the Balfour Declaration,” The Journal of Modern History 40, no. 4

(December 1968), 502.

37 Lebow, “Wilson and

the Balfour Declaration,” 501–523.

38 Martin Kramer,

“The Forgotten Truth about the Balfour Declaration,” Mosaic, June 5, 2017.

39 Ibid.

40 Ben Halpern, “The

Americanization of Zionism, 1880–1930,” American Jewish History 69, no. 1

(September 1979), 15–33.

41 In a letter sent

in 1910 to Jacob Schiff, one of the most prominent leaders of early twentieth

century American Jewry, Marshall wrote: “As you know, I am a non-Zionist but

not an anti-Zionist. I object fully as much as you do to being publicly connected

with a Zionistic undertaking. Yet I can see no objection to the acceptance of

financial aid from a Zionist or Zionistic organization.” See Jerome C.

Rosenthal, “A Fresh Look at Louis Marshall and Zionism 1900–1912,” American

Jewish Archives (November 1980), 115.

42 David Vital, A

People Apart (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 699.

43 Stuart E. Knee,

“Jewish Non-Zionism in America and Palestine Commitment: 1917–1941,” Jewish

Social Studies 39, no. 3 (Summer 1977), 210–211.

44 On Weizmann’s

complex relations with American Jews see Motti Golani and Jehuda Reinharz, The Founding Father: Chaim Weizmann, Biography

1922–1952 (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2020), 119–148 [Hebrew].

45 David S. Wyman,

The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust 1941–1945 (New York:

Pantheon Books, 1984).

For updates click homepage here