The strength of

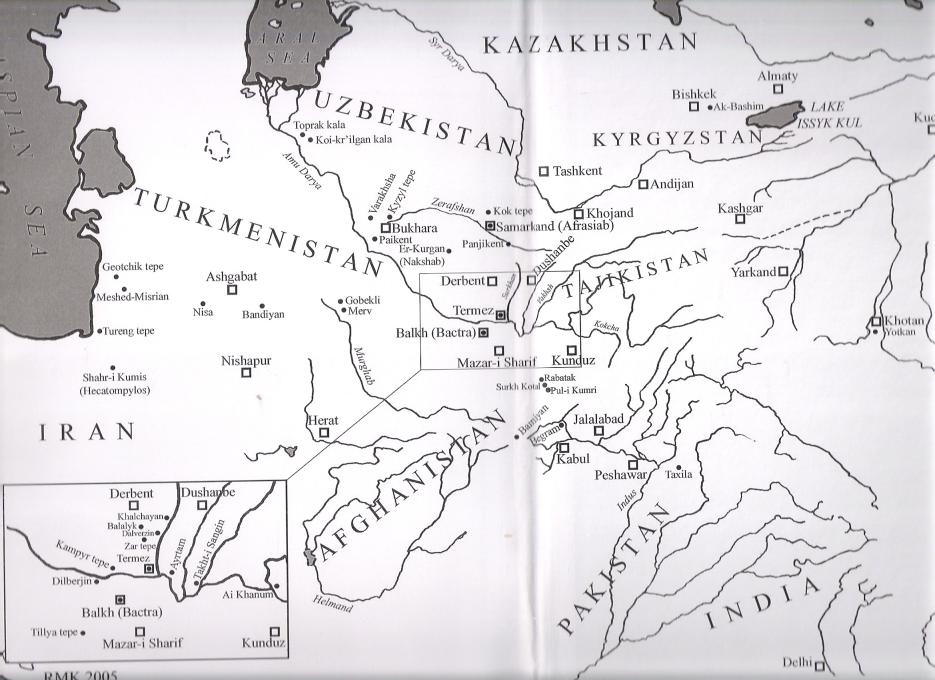

metropolitan development in Central Asia has a long history with urban

development that can be traced back to the Bronze Age and continuing under the Achaemenids

and the Greeks, following Alexander's brief incursion. The full flourishing of

these ancient cities, however, next seems to have taken place as a consequence

of the lengthy peace brought about by Kushan imperial rule. This millennium was

one of considerable prosperity in Central Asia, reflected by the remains of

numerous large cities, such as Merv, Toprak kala, Ayaz kala, Afrasiab, Varakhsha,

Panjikent, Termez, etc.

Following is a computer-aided reconstruction of the Hellenistic city of Ai

Khanum:

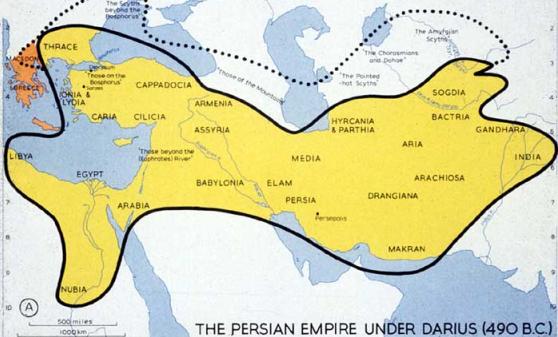

For

most classicists of the Mediterranean world, Central Asia is known essentially

for its Hellenistic past, beginning with the expedition of Alexander in 329-327

BC.] However, north of the Hindu Kush, this period, which ended between about

145 and 130 BC, was only a brief event in the history of the region. Since the

beginning of the Iron Age, Central Asian oases have known endless invasions and

migrations, and a permanent interaction between sedentary, semi-mobile and

nomadic populations is evident.

The

position of the frontier between Bactria and Sogdiana appears to have changed

between the Iron Age and the Kushan period, with a progressive reduction

northward of the territory of Sogdiana from the region of the Darya-i Pandj to the Baysun and Hissar ranges. The

geography of the Oxus and the Ochus as presented in the

sources for Alexander's expedition indicates that in the late Achaemenid and

Hellenistic periods the northern Bactrian frontier probably lay along the Amu-darya and the Wakhsh, rather than

at the Iron Gates or along the Amu-darya and the

Darya-i Pandj. This

research has no implications for the archaeology, since before the Kushans the

cultural context was very similar on both sides of the Oxus; it is doubtful

that the now traditional term 'Northern-Bactrian' for the right bank of the

Oxus-the classical Oxiana region-will ever be

changed, but subtleties should not be forgotten when historical interpretations

focus on defined 'ethnic' locations along the frontiers or peripheral regions.

As

can be inferred from the discoveries of Ai Khanum, Bactria was, in the

Hellenistic period, a major cultural centre, from

which Greek culture radiated throughout Central Asia. But, from an economic

point of view, nothing appears to prove that the GraecoBactrians

were interested economically by their position on the main crossroads of Asia.

The scarcity of coins on the site of Afrasiab and in its region is probably due

to the short time of Hellenistic power, but it also suggests that in the

Hellenistic period, trade in northern Sogdiana was not based on a developed

monetary system (GraecoBactrian coins were mainly

diffused in the form of imitations only by later nomad authorities). In

Bactria, on the other hand, the monetary finds do not present such concentration

as in the Indian area. So far as international commerce is concerned, the

imports to Ai Khanum are limited to a few 'occidental' products, like

Mediterranean plaster mouldings on metallic vases for

the Graeco-Bactrian artists, olive oil for the gymnasium activities, or books

for the library, whereas the Indian objects collected mainly in the treasury of

the palace have simply been identified as booty from Eucratides'

Indian expeditions against Menander. (After Alexandrer:

Central Asia before Islam, 2007, p.63.)

Another

constant of Central Asian life has been 'Invasion', either of expanding

imperial powers, such as Alexander and his successors or the Sasanian empire,

or by nomads, such as the Saka or Yuezhi.

Despite

their direct links represented, for example, by the eastern imports identified

at Nisa (Bactrian royal gifts or war booty?), the

Parthians were probably partially responsible for the economic isolation of the

Graeco-Bactrians from the western world. Before their disappearance, the

Graeco-Bactrian economy appears therefore to have been based more on local

natural resources and regional crafts than on any international commercial

potential, whereas the links perceived with the Indo-Greek world tended to be

of an ideological, political and military nature. Therefore, it is important to

underline the role of the nomads in the renewal of cultures and in the

development of international trade in Central Asia. The network of commercial

routes between China, India and the western world through the steppe and later

through the Indian Ocean corresponds to the so-called 'Silk Road'. Its real

beginning is difficult to date, and this event is not necessarily a direct

consequence of the disappearance of the Graeco- Bactrian rulers. The first

links with China in the last third of the second century Be are related to the

initiative of its emperor, who sent his ambassador Zhang Qian. The main

information provided by the report of this envoy is that all the roads between

China and Central Asia were controlled by mobile nomads. The identity of the

merchants active in Lan-shi (see above) is difficult

to determine. Their presence does coincide with the period of the plundering of

the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom, and does not imply the involvement of a wide

commercial system. Trade on a large scale probably begins later, when the

Scythian and Kushan power in northern India appears well established and

connected to the northern regions through roads affording sufficient security

to travellers. The opening of international trade is

therefore to be dated around the beginning of the first century AD, 57 in the

period represented by the rich nomad burials of Tillya

Tepe and Koktepe.

The

ethnic and cultural identities and migration routes of Central Asian nomadic

tribes present one of the most disputed questions of those related to the

Kushans. The tribes appear in literary sources preserved mainly in Chinese

chronicles and in scarce references in the works of Greek and Latin authors.

The migration of Central Asian nomads, particularly into Transoxiana can be

divided into two categories. The long 'trans-regional' route is ascribable to

the Yuezhi migration from the valley of Gansu, on the northern borders of

China, to the territory north of the Oxus River (Amu Darya), while the

migration of tribes like the Dahae, Sakaraules, Appasiakes, Parnes etc. can be classified as 'local' movements.

After

being defeated by the Xiongnu, the Yuezhi migrated

westwards. The first to clash with them were the Wusun. According to the

Chinese chronicles, the Wusun initially inhabited territory in eastern Turkestan

prior to being defeated by Xiongnu in 176 BC. In

about 160 BC, the Wusun moved to the area of Semirech'e

following the same path as the Yuezhi. According to this version of events the

locally found Wusun cultural remains must be dated no earlier than the second

century BC. However, some investigators also attribute monuments of both

earlier and later periods to the Wusun culture. They identify as Wusun most of

the necropolis remains of the third century BC to fifth century AD in Semirech'e, Tian Shan, the valley of Ta1as, and at the foot

of Karatau. This interpretation is not sufficiently

substantiated as it is based on the absence of reliable chronology and a

contradictory interpretation of literary sources. According to Kazim Abdullaev a leading Researcher at the Institute of

Archeology of Uzbekistan, literary sources recount how the Yuezhi on their long

journey from the valley of Gansu met different peoples. The first were the

Wusun. After their defeat by the Wusun in the region of Semirech'e,

the Yuezhi migrated further in a westerly direction. Passing through Da Yuan,

they reached the region between the two rivers of Amu Darya and Syr Darya. Here, north of the Oxus River, they found

another tribe already settled for some time, whom we can hypothetically

identify as the Sakaraules.

This

tribe is linked with the culture of the archaeological monuments of lower Syr Darya and is placed in eastern provinces of Khwarezm (Choresmia) and have

been identified with the Kangju. In approximately the

third to first half of the second century BC, these tribes migrated in a

southern direction and settled around the Samarkand and Bukhara oases. In all

probability, one can connect the representatives of the culture of the Orlat kurgans (tumuli) with the tribe of the Sakaraules, who dwelt in former times in the region of Kangju. If we follow this scheme further, the territory of

the Sakaraules accords with the description in

Strabo, who locates them as coming originally from the region beyond the

Jaxartes river.

The

discovery of a 'Sasanian' relief published in After Alexandrer:

Central Asia before Islam, 2007, found on a cliff in central Afghanistan,

rather than Iran, shows a rhinoceros hunt, which appears to symbolize a

Sasanian king's conquest of 'India'.

Buddhism

spread to Bactria in the Kushan period thanks to its support from the Kushan

nobility. In the first to third centuries there is a considerable flowering of

Buddhist art to be observed, mainly that of the monumental variety (sculpture,

wall-paintings), which was also made possible by support from the Kushan

nobility. Most of the work on the decoration of Buddhist monuments at that time

was undertaken by professional artists, who did not belong to the Buddhist

community. In their work they made use of the iconography of the two main centres of Buddhist art-Gandhara

and, to a lesser extent, Mathura. Analysis of the works of art in Bactria of

the Kushan period has shown that the influence of Buddhist iconography on

non-Buddhist art was minimal.

In

the early medieval period certain changes took place in the social composition

of the community of Buddhist believers in Bactria-Tokharistan.

Buddhism ceased to be merely a religion of the nobility and began to spread

among the ranks of the common people and probably not just in the towns. The

Buddhist buildings of Tokharistan were being

decorated by Buddhist artists by this time, and they were working within the

framework of the artistic tradition of the region. Examples have been recorded

of the influence of Buddhist iconography on non-Buddhist sculpture in the Early

Medieval period. In addition the main influence on the development of Buddhist

art in Tokharistan at that time was from Kashmir,

which became an important centre of Buddhist teaching

and art in the second half of the first millennium. The spread of Islam in Tokharistan put an end to the development of Buddhist art

in the region. Yet, the influence of Buddhist iconography is thought still to

be discernible in the Islamic art of Transoxania in

the tenth and eleventh centuries.

For updates click homepage

here